Virelai

A virelai is a form of medieval French verse used often in poetry and music. It is one of the three formes fixes (the others were the ballade and the rondeau) and was one of the most common verse forms set to music in Europe from the late thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries.

One of the most famous composers of virelai is Guillaume de Machaut (c. 1300–1377), who also wrote his own verse; 33 separate compositions in the form survive by him. Other composers of virelai include Jehannot de l'Escurel, one of the earliest (d. 1304), and Guillaume Dufay (c. 1400–1474), one of the latest.

By the mid-15th century, the form had become largely divorced from music, and numerous examples of this form (including the ballade and the rondeau) were written, which were either not intended to be set to music, or for which the music has not survived.

A virelai with only a single stanza is also known as a bergerette.

Musical virelai

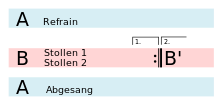

The virelai as a song form of the 14th and early 15th century usually has three stanzas, and a refrain that is stated before the first stanza and again after each. Within each stanza, the structure is that of the bar form, with two sections that share the same rhymes and music ("stollen"), followed by a third ("abgesang"). The third section of each stanza shares its rhymes and music with the refrain.[1][2]

Within this overall structure, the number of lines and the rhyme scheme is variable. The refrain and abgesang may be of three, four or five lines each, with rhyme schemes such as ABA, ABAB, AAAB, ABBA, AAAB, or AABBA.[2] The structure often involves an alternation of longer with shorter lines. Typically, all three stanzas share the same set of rhymes, which means that the entire poem may be built on just two rhymes, if the stollen sections also share their rhymes with the refrain.

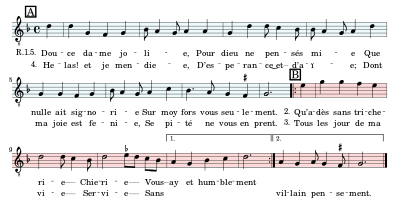

"Douce Dame Jolie" by Guillaume de Machaut is an example of a virelai with rhymes "AAAB" in the refrain, and "aab" (with a shortened second verse) in each of the stollen sections.

- Douce dame jolie,

- Pour dieu ne pensés mie

- Que nulle ait signorie

- Seur moy fors vous seulement.

- Qu'adès sans tricherie

- Chierie

- Vous ay et humblement

- Tous les jours de ma vie

- Servie

- Sans villain pensement.

- Helas! et je mendie

- D'esperance et d'aïe;

- Dont ma joie est fenie,

- Se pité ne vous en prent.

- Douce dame jolie,

- Pour dieu ne pensés mie

- Que nulle ait signorie

- Seur moy fors vous seulement.

Virelai "ancien" and "nouveau"

From the 15th century onwards the virelai was no longer regularly set to music but became a purely literary form, and its structural variety proliferated. The 17th-century prosodist Père Mourgues defined what he called the virelai ancien in a way that has little in common with the musical virelais of the 14th and 15th centuries. His virelai ancien is a structure without a refrain and with an interlocking rhyme scheme between the stanzas: in the first stanza, the rhymes are aab–aab–aab, with the "b" lines shorter than the "a" lines. In the second stanza, the "b" rhymes are shifted to the longer verses, and a new "c" rhyme is introduced for the shorter ones (bbc-bbc-bbc), and so on.[3] Another form described by Père Mourgues is the virelai nouveau, which has a two-line refrain at the beginning, with each stanza ending with a repetition of either the first or the second refrain verse in alternation, and the last stanza ending in both refrain verses in reversed order. These forms have occasionally been reproduced in later English poetry, e.g. by John Payne ("Spring Sadness", a virelai ancien), and Henry Austin Dobson ("July", a virelai nouveau).[3]

See also

References

- ↑ Harding, Carol E. "Virelai (Virelay)". In Michelle M. Sauer. The Facts on File Companion to British Poetry Before 1600. p. 450.

- 1 2 Heldt, Elisabeth (1916). Französische Virelais aus dem 15. Jahrhundert: Kritische Ausgabe mit Anmerkungen, Glossar und einer literarhistorischen und metrischen Untersuchung. Halle: Niemeyer. pp. 27–34.

- 1 2 Holmes, U. T.; Scott, C. "Virelai". In Roland Greene. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics. Princeton University Press. p. 1522.