Vincent van Gogh

| Vincent van Gogh | |

|---|---|

Self-Portrait, 1887, Art Institute of Chicago | |

| Born |

30 March 1853 Zundert, Netherlands |

| Died |

29 July 1890 (aged 37) Auvers-sur-Oise, France |

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Education | Anton Mauve |

| Known for | Painting, drawing |

| Notable work | Starry Night, Sunflowers, Bedroom in Arles, Portrait of Dr. Gachet, Sorrow |

| Movement | Post-Impressionism |

Vincent Willem van Gogh (Dutch: [ˈvɪnsɛnt ˈʋɪləm vɑn ˈɣɔx];[note 1][1] (30 March 1853 – 29 July 1890) was a Dutch post-Impressionist painter whose work had far-reaching influence on 20th-century art. His paintings include portraits, self portraits, landscapes, still lifes, olive trees and cypresses, wheat fields and sunflowers. He was largely ignored by critics until after his early death in 1890. The only substantial exhibitions held during his lifetime were showcases in Paris and Brussels. The first published full-length article came in 1890, when Albert Aurier described him as a Symbolist. The widespread and popular realisation of his significance in the history of modern art did not begin until his adoption by the Fauves and German Expressionists in the mid-1910s.

Vincent van Gogh was born to upper middle class parents and spent his early adulthood working for a firm of art dealers before travelling to The Hague, London and Paris, after which he taught in England at Isleworth and Ramsgate. Although he drew as a child, he did not paint until his late twenties; most of his best-known works were completed during the last two years of his life. He was deeply religious as a younger man and aspired to be a pastor and from 1879 worked as a missionary in a mining region in Belgium where he sketched people from the local community. His first major work was 1885's The Potato Eaters, from a time when his palette mainly consisted of sombre earth tones and showed no sign of the vivid colouration that distinguished his later paintings. In March 1886 he relocated to Paris and discovered the French Impressionists.

Later, he moved to the south of France and was influenced by the region's strong sunlight. His paintings grew brighter in colour, and he developed the unique and highly recognizable style that became fully realized during his stay in Arles in 1888. In just over a decade, he produced more than 2,100 artworks, including around 860 oil paintings and more than 1,300 watercolours, drawings, sketches and prints.

After years of anxiety and frequent bouts of mental illness he died aged 37 from a self-inflicted gunshot wound. The extent to which his mental health affected his painting has been widely debated. Despite a widespread tendency to romanticize his ill health, art historians see an artist deeply frustrated by the inactivity and incoherence wrought through illness. His late paintings show an artist at the height of his abilities, completely in control, and according to art critic Robert Hughes, "longing for concision and grace".[2]

Letters

.png)

The most comprehensive primary source for understanding Van Gogh is the collection of letters between him and his younger brother, art dealer Theo van Gogh.[5] They lay the foundation for most of what is known about his thoughts and beliefs.[6][7] Theo provided his brother with financial and emotional support. The brothers' lifelong friendship, and most of what is known of Vincent's thoughts and theories of art, is recorded in the hundreds of letters exchanged between 1872 and 1890. There are more than 600 from Vincent to Theo, and 40 from Theo to Vincent.

Although many are undated, art historians have generally been able to put them in chronological order. Problems remain, mainly in dating those from Arles, although it is known that during that period Van Gogh wrote around 200 letters to friends in Dutch, French and English.[8] The period when Vincent lived in Paris is the most difficult to analyse because the brothers lived together and had no need to correspond.[9] Along with the letters to and from Theo, there are other surviving documents including to Van Rappard, Émile Bernard, Van Gogh's sister Wil and her friend Line Kruysse.[10] The letters were annotated in 1913 by Theo's widow, Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, who later said that she published with "trepidation" because she did not want the details of the artist's life to overshadow his work.[5]

Biography

Early life

Vincent Willem van Gogh was born on 30 March 1853 in Groot-Zundert, a village close to Breda, in the predominantly Catholic province of North Brabant in the southern Netherlands.[11][12][1] He was the oldest surviving child of Theodorus van Gogh, a minister of the Dutch Reformed Church, and Anna Cornelia Carbentus. Vincent was given the name of his grandfather, and of a brother stillborn exactly a year before his birth.[note 2] The practice of reusing a name was not unusual. Vincent was a common name in the Van Gogh family: his grandfather, Vincent (1789–1874), received his degree of theology at the University of Leiden in 1811. Grandfather Vincent had six sons, three of whom became art dealers. Grandfather Vincent had perhaps been named in turn after his own father's uncle, the sculptor Vincent van Gogh (1729–1802).[13][14] The Van Gogh family tended to gravitate towards art and religion.

His brother Theo was born on 1 May 1857. He had another brother, Cor, and three sisters: Elisabeth, Anna, and Willemina "Wil".[15] Vincent was a serious and thoughtful child. He attended the village school at Zundert from 1860, where a single Catholic teacher taught around 200 pupils. From 1861, he and his sister Anna were taught at home by a governess, until 1 October 1864, when he was placed in Jan Provily's boarding school at Zevenbergen about 20 miles (32 km) away. He was distressed to leave his family home. From September 1866, he attended the new Willem II College middle school in Tilburg. Constantijn C. Huysmans, a successful artist in Paris, taught Van Gogh to draw at the school and advocated a systematic approach to the subject. Vincent's interest in art began at an early age. He began to draw as a child and continued making drawings throughout the years leading to his decision to become an artist. Though well-done and expressive,[16] his early drawings do not approach the intensity he developed in his later work.[17] In March 1868, Van Gogh abruptly returned home. In a 1883 letter to Theo he wrote, "My youth was gloomy and cold and sterile."[18]

In July 1869, his uncle Cent helped him obtain a position with the art dealer Goupil & Cie in The Hague. After his training, in June 1873, Goupil transferred him to London, where he lodged at 87 Hackford Road, Stockwell", and worked at Messrs. Goupil & Co., 17 Southampton Street.[19] This was a happy time for Vincent; he was successful at work and at 20 he earned more than his father. Theo's wife later remarked that this was the best year of his life. He fell in love with his landlady's daughter, Eugénie Loyer, but was rejected when he confessed his feelings; she said she was secretly engaged to a former lodger. Vincent grew further isolated and fervent about religion. His father and uncle arranged for his transfer to Paris where he grew resentful at how art was treated as a commodity, a fact he believed apparent to customers. On 1 April 1876, Goupil terminated his employment.[20]

Van Gogh moved to England for unpaid work as a supply teacher in a small boarding school in Ramsgate. When the proprietor relocated to Isleworth, Middlesex, Van Gogh moved with him.[21] The arrangement did not work out and he left to become a Methodist minister's assistant, following his wish to "preach the gospel everywhere".[22] At Christmas, he returned home and for six months took work at a bookshop in Dordrecht. He was unhappy in the position and spent his time either doodling or translating passages from the Bible into English, French and German.[23] According to his room-mate of the time, a young teacher named Görlitz, Van Gogh ate frugally, and preferred not to eat meat.[24][note 3] To support his new found religious conviction and efforts to become a pastor, his family sent him to Amsterdam to study theology in May 1877. There he stayed with his uncle Jan van Gogh, a naval Vice Admiral.[25][26] Vincent prepared for the entrance exam with his uncle Johannes Stricker, a respected theologian. He failed the exam, and left his uncle Jan's house in July 1878. He then undertook but failed, a three-month course at the Vlaamsche Opleidingsschool, a Protestant missionary school in Laeken, near Brussels.[27]

In January 1879, he took a temporary post as a missionary in the village of Petit Wasmes[note 4] in the coal-mining district of Borinage in Belgium at Charbonnage de Marcasse, Van Gogh lived like those he preached to, sleeping on straw in a small hut at the back of the baker's house where he was staying. The baker's wife reported hearing Van Gogh sobbing at night in the hut. His choice of squalid living conditions did not endear him to the appalled church authorities, who dismissed him for "undermining the dignity of the priesthood". He then walked to Brussels,[28] returned briefly to the village of Cuesmes in the Borinage, but gave in to pressure from his parents to return home to Etten. He stayed there until around March the following year,[note 5] a cause of increasing concern and frustration for his parents. There was particular conflict between Vincent and his father, who made inquiries about having Vincent committed to the lunatic asylum at Geel.[29][note 6]

He moved back to Cuesmes lodging with miner Charles Decrucq until October.[30] He was interested in the people and scenes around him and recorded his time there in his drawings, following Theo's suggestion that he take up art in earnest. He travelled to Brussels later in the year, to follow Theo's recommendation to study with the prominent Dutch artist Willem Roelofs, who persuaded him—in spite of his aversion to formal schools of art—to attend the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, where he registered on 15 November 1880. At the Académie, he studied anatomy and the standard rules of modelling and perspective, about which he said, "you have to know just to be able to draw the least thing."[31] Van Gogh aspired to become an artist in God's service, stating: "to try to understand the real significance of what the great artists, the serious masters, tell us in their masterpieces, that leads to God; one man wrote or told it in a book; another in a picture."[32]

Etten, Drenthe and The Hague

Van Gogh's parents moved to the Etten countryside in April 1881. He continued to draw, often using neighbours as subjects. During the first summer, he took long walks with his recently widowed cousin, Kee Vos-Stricker, daughter of his mother's older sister and Johannes Stricker.[33] Kee was seven years older and had an eight-year-old son. He proposed marriage but was refused with the words "No, nay, never" ("nooit, neen, nimmer").[34][35] Late that November, Van Gogh wrote a strongly worded letter to Johannes,[36] and left for Amsterdam but through letters maintained close contact.[37] Kee would not meet him, her parents wrote that his "persistence is disgusting." In desperation, he held his left hand in the flame of a lamp, with the words: "Let me see her for as long as I can keep my hand in the flame."[38] He did not recall the event well, but later assumed that his uncle blew out the flame. Kee's father made it clear to him that Kee's refusal should be heeded and that the two would not be married[39] because of Van Gogh's inability to support himself.[40] Van Gogh's perception of his uncle and former tutor's hypocrisy affected him deeply and put an end to his religious faith forever.[41] That Christmas, he refused to attend church, quarreling violently with his father as a result and leading him to leave home the same day for The Hague.[42][43]

He settled in The Hague in January 1882, where he visited his cousin-in-law, Anton Mauve. Mauve introduced him to painting in oil and watercolour and lent money to set up a studio,[44] but they fell out, possibly over the viability of drawing from plaster casts.[45] Van Gogh's uncle Cornelis, an art dealer, commissioned 12 ink drawings of views of the city which Van Gogh completed soon after arriving in the city, along with seven other drawings that May.[46] In June he suffered a bout of gonorrhoea and spent three weeks in hospital,[47] but that summer began to paint in oil.[48]

Mauve appears to have suddenly gone cold towards Van Gogh and stopped returning of his letters.[49] He supposed that Mauve had learned of his new domestic arrangement with an alcoholic prostitute, Clasina Maria "Sien" Hoornik (1850–1904), and her young daughter.[50][51] He had met Sien towards the end of January, when she had a five-year-old daughter and was pregnant. She had already borne two children who died, although Van Gogh was unaware of this;[52] and on 2 July, she gave birth to a baby boy, Willem.[53] When Van Gogh's father discovered the details of their relationship, he put pressure on his son to abandon Sien and her children, although Vincent at first defied him.[54] Vincent considered moving the family out of the city, but in late 1883 left Sien and the two children.[55] Perhaps lack of money pushed Sien back into prostitution; the home became less happy while Van Gogh may have felt family life was irreconcilable with his artistic development. When he left, Sien gave her daughter to her mother and baby Willem to her brother. She then moved to Delft, and later to Antwerp.[56]

Willem remembered being taken to visit his mother in Rotterdam at around the age of 12, where his uncle tried to persuade Sien to marry in order to legitimize the child. Willem recalled his mother saying, "But I know who the father is. He was an artist I lived with nearly 20 years ago in The Hague. His name was Van Gogh." She then turned to Willem and said "You are called after him."[57] While he believed himself Van Gogh's son, the timing of his birth makes this unlikely.[58] In 1904, Sien drowned herself in the River Scheldt.[59] Van Gogh moved to the Dutch province of Drenthe, in the northern Netherlands. That December, driven by loneliness, he went to stay with his parents, who had been posted to Nuenen, North Brabant.[59]

Emerging artist

Nuenen and Antwerp (1883–1886)

In Nuenen, Van Gogh devoted himself to drawing and gave money to boys to bring him birds' nests for subject matter for paintings,[note 7] and he made many sketches and paintings of weavers in their cottages.[60] In late 1884, Margot Begemann, a neighbour's daughter and ten years his senior, often joined him on his painting forays. She fell in love, and he reciprocated – though less enthusiastically. They decided to marry, but the idea was opposed by both families. As a result, Margot took an overdose of strychnine. She was saved when Van Gogh rushed her to a nearby hospital.[53] On 26 March 1885, his father died of a heart attack, and he grieved deeply at the loss.[61]

For the first time there was interest from Paris in his work. Early that year he completed what is generally considered his first major work, The Potato Eaters, the culmination of several years work painting peasant character studies.[62] In August 1885, his work was first exhibited in the windows of the paint dealer Leurs in The Hague. After one of his young peasant sitters became pregnant that September, Van Gogh was accused of forcing himself upon her[note 8] and the Catholic village priest forbade parishioners from modeling for him.[63]

He painted several groups of still-life paintings in 1885; Still-Life with Straw Hat and Pipe and Still-life with Earthen Pot and Clogs are characterized by smooth, meticulous brushwork and fine shading of colours.[64] During his two-year stay in Nuenen, he completed numerous drawings and watercolours and nearly 200 oil paintings. His palette consisted mainly of sombre earth tones, particularly dark brown, but showed no sign of developing the vivid colouration that distinguishes his later work. When he complained that Theo was not making enough effort to sell his paintings in Paris, his brother responded that the paintings were too dark and not in line with the current style of bright Impressionist paintings.[65] He moved to Antwerp in November 1885, where he rented a small room above a paint dealer's shop in the Rue des Images (Lange Beeldekensstraat).[66] He lived in poverty and ate poorly, preferring to spend money Theo sent on painting materials and models. Bread, coffee and tobacco were his staple intake. In February 1886, he wrote to Theo saying that he could only remember eating six hot meals since May of the previous year. His teeth became loose and painful.[67] In Antwerp he applied himself to the study of colour theory and spent time in museums, particularly studying the work of Peter Paul Rubens, gaining encouragement to broaden his palette to carmine, cobalt and emerald green. He bought Japanese Ukiyo-e woodcuts in the docklands, and incorporated their style into the background of some of his paintings.[68]

Van Gogh began to drink absinthe heavily.[69] He was treated by Dr. Amadeus Cavenaile, whose practice was near the docklands,[note 9] possibly for syphilis;[note 10] the treatment of alum irrigation and sitz baths was jotted down by Van Gogh in one of his notebooks.[70] Despite his rejection of academic teaching, he took the higher-level admission exams at the Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, and, in January 1886, matriculated in painting and drawing. For most of February, he was ill and run down by overwork, a poor diet, and excessive smoking.[71]

Paris (1886–1888)

Van Gogh travelled to Paris in March 1886, where he shared Theo's Rue Laval apartment on Montmartre, to study at Fernand Cormon's studio. In June, they took a larger apartment at 54 Rue Lepic. Because they had no need to write letters to communicate, little is known about this stay in Paris.[72] In Paris, he painted portraits of friends and acquaintances, still-life paintings, views of Le Moulin de la Galette, scenes in Montmartre, Asnières, and along the Seine. During his stay he collected more Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints; he became interested in Japonaiserie when, in 1885 in Antwerp, he used them to decorate the walls of his studio. He collected hundreds of prints, examples are visible in the backgrounds of several of his paintings; several can be seen hanging on the wall of his 1887 Portrait of Père Tanguy. In The Courtesan or Oiran (after Kesai Eisen) (1887), Van Gogh traced the figure from a reproduction on the cover of the magazine Paris Illustre, which he then graphically enlarged in the painting.[73] His 1888 Plum Tree in Blossom (After Hiroshige) is a vivid example of the admiration he had for the prints he collected. His version is slightly bolder than Hiroshige's original.[74]

After seeing Adolphe Joseph Thomas Monticelli at the Galerie Delareybarette Van Gogh adopted a brighter palette and a bolder attack, particularly in paintings such as his Seascape at Saintes-Maries (1888).[75][76] Two years later, Vincent and Theo paid for the publication of a book on Monticelli paintings, and Vincent bought some of his works, to add to his collection.[77]

For months, Van Gogh worked at Cormon's studio, where he frequented the circle of the British-Australian artist John Peter Russell,[78] and met fellow students like Émile Bernard, Louis Anquetin, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec – who painted a portrait of Van Gogh with pastel. The group congregated at Julien "Père" Tanguy's paint store (which was, at that time, the only place where Paul Cézanne's paintings were displayed). He had easy access to Impressionist works in Paris at the time. In 1886, two large vanguard exhibitions were staged; shows where Neo-Impressionism was first exhibited, bringing attention to Georges Seurat and Paul Signac. Though Theo kept a stock of Impressionist paintings in his gallery on Boulevard Montmartre, Van Gogh seemingly had problems acknowledging developments in how artists view and paint their subject matter.[79]

Conflicts arose between the brothers. At the end of 1886, Theo found that living with Vincent was "almost unbearable". By early 1887, they were again at peace, although Van Gogh moved to Asnières, a northwestern suburb of Paris, where he became acquainted with Signac. With Émile Bernard, he adopted elements of Pointillism, a technique in which a multitude of small coloured dots are applied to the canvas such that—when seen from a distance—they create an optical blend of hues.[80] The style stresses the value of complementary colours—including blue and orange—to form vibrant contrasts that are enhanced when juxtaposed.[81]

While in Asnières, he painted parks and restaurants and the Seine, including Bridges across the Seine at Asnieres. In November 1887, Theo and Vincent befriended Paul Gauguin who had just arrived in Paris.[82] Towards the end of the year, Vincent arranged an exhibition alongside Bernard, Anquetin, and probably Toulouse-Lautrec, at the Grand-Bouillon Restaurant du Chalet, 43 Avenue de Clichy, Montmartre. In a contemporary account, Émile Bernard wrote: "On the avenue de Clichy a new restaurant was opened. Vincent used to eat there. He proposed to the manager that an exhibition be held there .... Canvases by Anquetin, by Lautrec, by Koning ...filled the hall....It really had the impact of something new; it was more modern than anything that was made in Paris at that moment."[83] There Bernard and Anquetin sold their first paintings, and Van Gogh exchanged work with Gauguin, who soon departed to Pont-Aven. Discussions on art, artists, and their social situations that started during this exhibition continued and expanded to include visitors to the show, like Pissarro and his son Lucien, Signac, and Seurat. Finally, in February 1888, feeling worn out from life in Paris, Vincent left, having painted over 200 paintings during his two years in the city. Only hours before his departure, accompanied by Theo, he paid his first and only visit to Seurat in his atelier (studio).[84]

Artistic breakthrough and final years

Move to Arles (1888–1889)

.jpg)

Ill from drink and suffering from smoker's cough Van Gogh moved to take refuge in Arles.[8] He arrived on 21 February 1888, and took room at the Hôtel-Restaurant Carrel.[8] He seems to have moved to the town with thoughts of founding a utopian art colony. The Danish artist Christian Mourier-Petersen (1858–1945) became his companion for two months, and at first Arles appeared exotic and filthy. In a letter, he described it as a foreign country: "The Zouaves, the brothels, the adorable little Arlesiennes going to their First Communion, the priest in his surplice, who looks like a dangerous rhinoceros, the people drinking absinthe, all seem to me creatures from another world."[85] Van Gogh was enchanted by the local landscape and light and his works from this period are richly draped in yellow, ultramarine, and mauve. His portrayals of the Arles landscape are informed by his Dutch upbringing; the patchwork of fields and avenues appear flat and lacking perspective, but excel in their colourisation.[8][85] The light in Arles excited him, and his newfound appreciation is seen in the range and scope of his work. That March he painted landscapes using a gridded "perspective frame"; three of these paintings were shown at the annual exhibition of the Société des Artistes Indépendants. In April, he was visited by the American artist Dodge MacKnight, who was living nearby at Fontvieille.[3][86] On 1 May, he signed a lease for 15 francs per month in the eastern wing of the Yellow House at No. 2 Place Lamartine. The rooms were unfurnished and uninhabited for some time.[87]

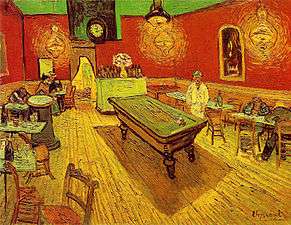

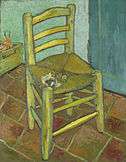

He moved from the Hôtel Carrel to the Café de la Gare on 7 May,[88] where he befriended the proprietors, Joseph and Marie Ginoux. Although the Yellow House had to be furnished before he could fully move in, Van Gogh was able to utilize it as a studio.[89] Hoping to have a gallery to display his work, his project at this time was a series of paintings including Van Gogh's Chair (1888), Bedroom in Arles (1888), The Night Café (1888), Cafe Terrace at Night (September 1888), Starry Night Over the Rhone (1888), and Still Life: Vase with Twelve Sunflowers (1888), all intended to form the décoration for the Yellow House.[90] Van Gogh wrote about The Night Café: "I have tried to express the idea that the café is a place where one can ruin oneself, go mad, or commit a crime."[91]

When he visited Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer that June, he gave lessons to a Zouave second lieutenant—Paul-Eugène Milliet[92] —and painted boats on the sea and the village.[93] MacKnight introduced Van Gogh to Eugène Boch, a Belgian painter who stayed at times in Fontvieille, and the two exchanged visits in July.[92]

Gauguin's visit

.jpg)

When Gauguin agreed to visit Arles, Van Gogh hoped for friendship, and the realization of his utopian idea of an artists collective. That August he painted sunflowers. When Boch visited again, Van Gogh painted a portrait of him, as well as the study The Poet Against a Starry Sky. Boch's sister Anna (1848–1936), also an artist, purchased The Red Vineyard in 1890.[94][95] In preparation for Gauguin's visit, Van Gogh bought two beds on advice from his friend the station's postal supervisor Joseph Roulin, whose portrait he painted, and on 17 September spent the first night in the still sparsely furnished Yellow House.[96][97] When Gauguin consented to work and live side-by-side in Arles with Van Gogh, he started to work on The Décoration for the Yellow House, probably the most ambitious effort he ever undertook.[98] Van Gogh completed two chair paintings: Van Gogh's Chair and Gauguin's Chair.[99]

Gauguin, after much pleading, finally arrived in Arles on 23 October. That November, the two finally painted together. Gauguin depicted Van Gogh in his The Painter of Sunflowers: Portrait of Vincent van Gogh, while, uncharacteristically, Van Gogh painted pictures from memory (deferring to Gauguin's ideas) and his The Red Vineyard. Among these "imaginative" paintings is Memory of the Garden at Etten.[100][101] Their first joint outdoor venture was at the Alyscamps, when they produced Les Alyscamps.[102]

They visited Montpellier that December, where they saw works by Courbet and Delacroix in the Musée Fabre.[103] However, their relationship began to deteriorate. Van Gogh admired Gauguin and desperately wanted to be treated as his equal, but Gauguin was arrogant and domineering, something that often frustrated Van Gogh. They quarreled about art; Van Gogh increasingly feared that Gauguin was going to desert him, and the situation, which Van Gogh described as one of "excessive tension," rapidly headed towards a crisis point.[104]

The exact sequence of events that led to Van Gogh's removal of his ear is not known. The only account attesting a supposed earlier razor attack on Gauguin comes from Gauguin himself some fifteen years later, and biographers agree this account must be considered unreliable and self-serving.[105][106] However, it does seem likely that, by 23 December 1888, Van Gogh had realized that Gauguin was proposing to leave and that there had been some kind of contretemps between the two.[107] That evening, Van Gogh severed his left ear (either wholly or in part; accounts differ) with a razor, inducing a severe haemorrhage.[note 11] He bandaged his wound, wrapped the ear in paper, and delivered the package to a brothel frequented by both him and Gauguin, before returning home and collapsing. He was found unconscious the next day by the police[note 12] and taken to the hospital.[108] The local newspaper reported that Van Gogh had given the ear to a prostitute with an instruction to guard it carefully.[109][110]

Gauguin's account implies that Van Gogh left his ear with the doorman as a memento for Gauguin. Van Gogh himself had no recollection of these events, and it is plain that he had suffered an acute psychotic episode.[111] Family letters of the time make it clear that the event had not been unexpected.[112] He had suffered a nervous collapse in Antwerp some three years before, and as early as 1880 his father had proposed committing him to an asylum (at Gheel).[113] The hospital diagnosis was "generalized delirium", and within a few days it was decided to keep him in the hospital against his will.[112]

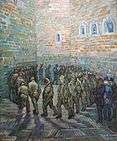

Limited access to the world outside the clinic resulted in a shortage of subject matter. He was left to work on interpretations of other artist's paintings, such as Millet's The Sower and Noon – Rest from Work (after Millet), as well as variations on his own earlier work. Van Gogh was an admirer of the Realism of Jules Breton, Gustave Courbet, and Millet,[114] and he compared his copies to a musician's interpreting Beethoven.[115][116] His The Round of the Prisoners (1890) was painted after an engraving by Gustave Doré (1832–1883). It is suggested that the face of the prisoner in the centre of the painting and looking toward the viewer is Van Gogh himself, although the noted Van Gogh scholar Jan Hulsker discounts this.[117][118] During the initial few days of his treatment, Van Gogh repeatedly asked for Gauguin, but Gauguin stayed away. Gauguin told one of the policeman attending the case, "Be kind enough, Monsieur, to awaken this man with great care, and if he asks for me tell him I have left for Paris; the sight of me might prove fatal for him."[119] Gauguin wrote of Van Gogh, "His state is worse, he wants to sleep with the patients, chase the nurses, and washes himself in the coal bucket. That is to say, he continues the biblical mortifications."[112][119] Theo was notified by Gauguin and visited, as did both Madame Ginoux and Roulin. Gauguin left Arles never to see Van Gogh again.[note 13]

Despite the pessimistic diagnosis, Van Gogh recovered and returned to the Yellow House by the beginning of January. However he spent the following month between hospital and home, suffering from hallucinations and delusions of poisoning. That March, the police closed his house after a petition by 30 townspeople (including the Ginoux family) who described him as "le fou roux" (the redheaded madman).[112] Paul Signac spent time with him in the hospital, and Van Gogh was allowed home in his company. In April, he moved into rooms owned by his physician Dr. Rey after floods damaged paintings in his own home.[120][121] Around this time, he wrote, "Sometimes moods of indescribable anguish, sometimes moments when the veil of time and fatality of circumstances seemed to be torn apart for an instant." Two months later, he left Arles and, at his own request, entered an asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence.[122]

Saint-Rémy (May 1889 – May 1890)

Van Gogh entered the hospital at Saint Paul-de-Mausole on 8 May 1889 accompanied by his carer, the Reverend Salles. The hospital was a former monastery in Saint-Rémy less than 20 miles (32 km) from Arles, located in an area of cornfields, vineyards and olive trees, and at the time run by a former naval doctor, Dr. Théophile Peyron. He had two small rooms: adjoining cells with barred windows. The second was to be used as a studio.[123]

During his stay, the clinic and its garden became the main subjects of his paintings. He made several studies of the hospital interiors, such as Vestibule of the Asylum and Saint-Remy (September 1889). Some of the work from this time is characterized by swirls, including The Starry Night, one of his best-known paintings. He was allowed short supervised walks, which led to paintings of cypresses and olive trees, such as Olive Trees with the Alpilles in the Background 1889, Cypresses 1889, Cornfield with Cypresses (1889), Country road in Provence by Night (1890). That September, he produced a further two versions of Bedroom in Arles.

Between February and April 1890 Van Gogh suffered a severe relapse. Nevertheless, he was able to paint and draw a little during this time, and he later wrote Theo that he had made a few small canvases "from memory ... reminisces of the North."[124] Amongst these was Two Peasant Women Digging in a Snow-Covered Field at Sunset. Hulsker believes that this small group of paintings formed the nucleus of many drawings and study sheets depicting landscapes and figures that Van Gogh worked on during this time. He comments that—save for this short period—Van Gogh's illness had hardly any effect on his work, but in these he sees a reflection of Van Gogh's mental health at the time.[125] Also belonging to this period is Sorrowing Old Man ("At Eternity's Gate"), a colour study that Hulsker describes as "another unmistakable remembrance of times long past."[125][126]

In February 1890, he painted five versions of L'Arlésienne (Madame Ginoux), based on a charcoal sketch Gauguin had produced when Madame Ginoux sat for both artists at the beginning of November 1888.[127] The version intended for Madame Ginoux is lost. It was attempting to deliver this painting to Madame Ginoux in Arles that precipitated his February relapse.[128] His work was praised by Albert Aurier in the Mercure de France in January 1890, when he was described as "a genius".[129] That February, he was invited by Les XX, a society of avant-garde painters in Brussels, to participate in their annual exhibition. At the opening dinner, Les XX member Henry de Groux insulted Van Gogh's work. Toulouse-Lautrec demanded satisfaction, while Signac declared he would continue to fight for Van Gogh's honor if Lautrec should surrender. Later, while Van Gogh's exhibit was on display with the Artistes Indépendants in Paris, Monet said that his work was the best in the show.[130] In February 1890, following the birth of his nephew Vincent Willem, he wrote in a letter to his mother that, with the new addition to the family, he "started right away to make a picture for him, to hang in their bedroom, branches of white almond blossom against a blue sky."[131]

Auvers-sur-Oise (May–July 1890)

In May 1890, Van Gogh left the clinic in Saint-Rémy to move nearer the physician Dr. Paul Gachet in Auvers-sur-Oise, and also to Theo. Gachet was recommended by Camille Pissarro who had treated several other artists and was himself an amateur artist. Van Gogh's first impression was that Gachet was "...sicker than I am, I think, or shall we say just as much."[133] In June 1890, he painted several portraits of the physician, including Portrait of Dr. Gachet, and his only etching; in each, the emphasis is on Gachet's melancholic disposition. Van Gogh stayed at the Auberge Ravoux, where rented a small attic room.

During his last weeks at Saint-Rémy, Van Gogh's thoughts returned to his "memories of the North",[134] and several of the approximately 70 oils painted during his 70 days in Auvers-sur-Oise, such as The Church at Auvers, are reminiscent of northern scenes.[135]

Wheat Field with Crows, painted in July 1890, is among his most haunting and elemental works.[136] It is often mistakenly believed to be his last work, but Hulsker lists seven paintings that postdate it.[137]

Barbizon painter Charles Daubigny had moved to Auvers in 1861, and this in turn drew other artists there, including Camille Corot and Honoré Daumier. In July 1890, Van Gogh completed two paintings of Daubigny's Garden; one of which is likely his final work. There are other paintings that show evidence of being unfinished, including Thatched Cottages by a Hill.[136]

Death

Oil on canvas, 65 × 54 cm

Musée d'Orsay, Paris. This may have been Van Gogh's last self-portrait.[138]

On 22 February 1890, Van Gogh suffered a new crisis that was "the starting point for one of the saddest episodes in a life already rife with sad events," according to Hulsker. From February until the end of April he was unable to bring himself to write, though he did continue to draw and paint,[128] which follows a pattern begun the previous May, in 1889. For a year he "had fits of despair and hallucination during which he could not work, between long clear months in which he could and did, punctuated by extreme visionary ecstasy."[139]

On 27 July 1890, aged 37, Van Gogh shot himself in the chest with a revolver (although no gun was ever found).[140] There were no witnesses and the location where he shot himself is unclear. Ingo Walther writes, "Some think Van Gogh shot himself in the wheat field that had engaged his attention as an artist of late; others think he did it at a barn near the inn."[141] Biographer David Sweetman writes that the bullet was deflected by a rib bone and passed through his chest without doing apparent damage to internal organs—probably stopped by his spine. He was able to walk back to the Auberge Ravoux, where he was attended by two physicians. However, without a surgeon present the bullet could not be removed. After tending to him as best they could, the physicians left him alone in his room, smoking his pipe. The following morning, a Monday, Theo rushed to his brother as soon as notified, and found him in surprisingly good shape. But within hours Vincent began to fail, suffering from an untreated infection resulting from the wound. He died that evening, 29 hours after the gunshot wound. According to Theo, Vincent's last words were: "The sadness will last forever".[140][142]

Van Gogh was buried on 30 July in the municipal cemetery of Auvers-sur-Oise. The funeral was attended by Theo van Gogh, Andries Bonger, Charles Laval, Lucien Pissarro, Émile Bernard, Julien Tanguy and Dr. Gachet amongst some 20 family, friends and locals. The funeral was described by Émile Bernard in a letter to Albert Aurier.[143][144] Theo suffered from syphilis and his health declined rapidly after Vincent's death. Weak and unable to come to terms with Vincent's absence, he died six months later, on 25 January, at Den Dolder, and he was buried in Utrecht.[145][146] In 1914, the year she had Van Gogh's letters published, Jo Bonger had Theo's body exhumed, moved from Utrecht and re-buried with Vincent at Auvers-sur-Oise.[147][148]

While many of his late paintings are somber, they can be seen as essentially optimistic and reflective of a desire to return to lucid mental health. Yet some of his final works reflect deepening concerns. Referring to his paintings of wheatfields under troubled skies, he commented in a letter to his brother Theo: "I did not have to go out of my way very much in order to try to express sadness and extreme loneliness." Nevertheless, he mentions that: "these canvases will tell you what I cannot say in words, that is, how healthy and invigorating I find the countryside."[149][150]

There has been much debate as to the source of Van Gogh's illness and its effect on his work. Over 150 psychiatrists have attempted to label its root, with some 30 different diagnoses.[151] Diagnoses include schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, syphilis, poisoning from swallowed paints, temporal lobe epilepsy, and acute intermittent porphyria. Any of these could have been the culprit, and could have been aggravated by malnutrition, overwork, insomnia, and consumption of alcohol, especially absinthe.

Work

Van Gogh drew and painted with watercolours while at school—only a few survive and authorship is challenged on some of those that do.[152] When he committed to art as an adult, he began at an elementary level, copying the Cours de dessin, a drawing course edited by Charles Bargue. Within two years he sought commissions. In early 1882, his uncle, Cornelis Marinus, owner of a well-known gallery of contemporary art in Amsterdam, asked him for drawings of the Hague. Van Gogh's work did not live up to his uncle's expectations. Marinus offered a second commission, this time specifying the subject matter in detail, but was once again disappointed with the result. Nevertheless, Van Gogh persevered. He improved the lighting of his studio by installing variable shutters and experimented with a variety of drawing materials. For more than a year he worked on single figures – highly elaborated studies in "Black and White",[153] which at the time gained him only criticism. Today, they are recognized as his first masterpieces.[154]

Early in 1883, he began to work on multi-figure compositions, which he based on his drawings. He had some of them photographed, but when his brother remarked that they lacked liveliness and freshness, he destroyed them and turned to oil painting. By late 1882, his brother had enabled him financially to turn out his first paintings, but all the money Theo could supply was soon spent. Then, in early 1883, Van Gogh turned to renowned Hague School artists like Weissenbruch and Blommers, and received technical support from them, as well as from painters like De Bock and Van der Weele, both second generation Hague School artists.[155] When he moved to Nuenen after the intermezzo in Drenthe he began several large-sized paintings but destroyed most of them. The Potato Eaters and its companion pieces – The Old Tower on the Nuenen cemetery and The Cottage – are the only ones to have survived. Following a visit to the Rijksmuseum, Van Gogh was aware that many of his faults were due to lack of technical experience.[155] So in November 1885 he travelled to Antwerp and later to Paris to learn and develop his skill.[156]

After becoming familiar with Impressionist and Neo-Impressionist techniques and theories, Van Gogh went to Arles to develop on these new possibilities. But within a short time, older ideas on art and work reappeared: ideas such as working with serial imagery on related or contrasting subject matter, which would reflect on the purposes of art. As his work progressed, he painted many Self-portraits. Already in 1884 in Nuenen he had worked on a series that was to decorate the dining room of a friend in Eindhoven. Similarly in Arles, in early 1888 he arranged his Flowering Orchards into triptychs, began a series of figures that found its end in The Roulin Family series, and finally, when Gauguin had consented to work and live in Arles side-by-side with Van Gogh, he started to work on The Décorations for the Yellow House, which was by some accounts the most ambitious effort he ever undertook.[98] Most of his later work is involved with elaborating on or revising its fundamental settings. In early 1889, he painted another, smaller group of orchards. In an April letter to Theo, he said, "I have 6 studies of Spring, two of them large orchards. There is little time because these effects are so short-lived."[157]

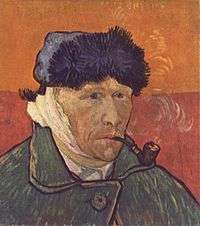

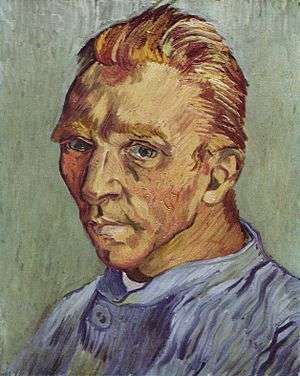

Self portraits

.jpg)

Van Gogh produced many self-portraits during his lifetime; he drew or painted more than 43 between 1886 and 1889.[159][160] They vary in intensity and colour, and some portray the artist with beard, some without, and others with bandages – in the period after he had severed a portion of his ear. Self-portrait Without Beard, from late September 1889, was one of the most expensive paintings ever sold at the time of its 1998 sale, when it went for $71.5 million in New York. It was also Van Gogh's last self-portrait, completed as a birthday gift to his mother.[161]

The self-portraits painted in Saint-Rémy show the artist's head from the right, that is opposite his mutilated ear; he painted himself reflected in his mirror.[162][163][164] During the final weeks of his life in Auvers-sur-Oise, he produced many paintings, but no self-portraits, a period in which he returned to painting the natural world.[165]

Portraits

.jpeg)

Although Van Gogh is best known for his landscapes, he seemed to have believed that portraits were his greatest ambition.[166] He said of portrait studies, "The only thing in painting that excites me to the depths of my soul, and which makes me feel the infinite more than anything else."[167]

He wrote to his sister that he "should like to paint portraits which appear after a century to people living then as apparitions...I do not endeavor to achieve this through photographic resemblance, but my means of our impassioned emotions – that is to say using our knowledge and our modern taste for colour as a means of arriving at the expression and the intensification of the character."[166]

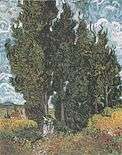

Cypresses

One of Van Gogh's most popular and widely known series is his cypresses. In mid-1889, at sister Wil's request, he made several smaller versions of Wheat Field with Cypresses.[168] These works are characterised by swirls and densely painted impasto, and produced one of his best-known paintings, The Starry Night. Other works from the series include Olive Trees with the Alpilles in the Background (1889) Cypresses (1889), Cypresses with Two Figures (1889–1890), Wheat Field with Cypresses (1889), (Van Gogh made several versions of this painting that year), Road with Cypress and Star (1890), and Starry Night Over the Rhone (1888). They have become synonymous with Van Gogh's work through their stylistic uniqueness.

According to art historian Ronald Pickvance, Road with Cypress and Star (1890), is compositionally as unreal and artificial as The Starry Night. Pickvance goes on to say the painting Road with Cypress and Star represents an exalted experience of reality, a conflation of North and South, what both Van Gogh and Gauguin referred to as an "abstraction". Referring to Olive Trees with the Alpilles in the Background, on or around 18 June 1889, in a letter to Theo, he wrote, "At last I have a landscape with olives and also a new study of a Starry Night."[169]

Hoping to obtain a gallery for his work, his undertook a series of paintings including Still Life: Vase with Twelve Sunflowers (1888), and Starry Night Over the Rhone (1888), all intended to form the décorations for the Yellow House.[170][171]

Flowering Orchards

The series of Flowering Orchards, sometimes referred to as the Orchards in Blossom paintings, were among the first groups of work that Van Gogh completed after his arrival in Arles, Provence in February 1888. The 14 paintings in this group are optimistic, joyous and visually expressive of the burgeoning Springtime. They are delicately sensitive, silent, quiet and unpopulated. About The Cherry Tree Vincent wrote to Theo on 21 April 1888 and said he had 10 orchards and: one big (painting) of a cherry tree, which I've spoiled.[172] Early the following year he painted another smaller group of orchards, including View of Arles, Flowering Orchards.[157] Van Gogh was consumed by the landscape and vegetation of the South of France, and often visited the farm gardens near Arles. Because of the vivid light supplied by the Mediterranean climate his palette significantly brightened.[173]

Flowers

Van Gogh painted several landscapes with flowers, including his View of Arles with Irises, and paintings of flowers, including Irises, Sunflowers,[174] lilacs and roses. Some reflect his interests in the language of colour, and also in Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints.[175] He completed two series of sunflowers. The first dated from his 1887 stay in Paris, the second during his visit to Arles the following year. The Paris series shows living flowers in the ground, in the second, they are dying in vases. The 1888 paintings were created during a rare period of optimism for the artist. He intended them to decorate a bedroom where Gauguin was supposed to stay in Arles that August, when the two would create the community of artists Van Gogh had long hoped for. The flowers are rendered with thick brushstrokes and heavy layers of paint.[176]

He wrote in an August 1888 letter to Theo, "I am hard at it, painting with the enthusiasm of a Marseillais eating bouillabaisse, which won't surprise you when you know that what I'm at is the painting of some sunflowers. If I carry out this idea there will be a dozen panels. So the whole thing will be a symphony in blue and yellow. I am working at it every morning from sunrise on, for the flowers fade so quickly. I am now on the fourth picture of sunflowers. This fourth one is a bunch of 14 flowers ... it gives a singular effect."[176]

Wheat fields

_-_Wheat_Field_with_Crows_(1890).jpg)

Van Gogh made several excursions into nature during his time around Arles. His paintings include harvests, wheat fields, and general rural landmarks from the area, including The Old Mill (1888); a good example of a picturesque structure bordering the wheat fields.[177] This was one of seven canvases sent to Pont-Aven on 4 October 1888 in exchange for works with Paul Gauguin, Émile Bernard, Charles Laval and others.[177] At various times Van Gogh painted the view from his window – at The Hague, Antwerp, and Paris. They culminate in The Wheat Field series, which depict the scene visible from his adjoining cells in the Saint-Rémy asylum.[178]

Writing in July 1890, after he had already moved to Auvers, Van Gogh said that he had become absorbed "in the immense plain against the hills, boundless as the sea, delicate yellow."[179] He had become captivated by the fields in May when the wheat was young and green. The weather worsened in July, and he wrote to Theo of "vast fields of wheat under troubled skies", adding that he did not "need to go out of my way to try and express sadness and extreme loneliness."[180] In particular, the work Wheatfield with Crows serves as a compelling and poignant expression of the artist's state of mind in his final days, a painting Hulsker discusses as being associated with "melancholy and extreme loneliness," a painting with a "somber and threatening aspect", a "doom-filled painting with threatening skies and ill-omened crows."[181] Hulsker identifies seven oil paintings as following the completion of the Wheatfield with Crows in July 1890 while in Auvers.[182]

Legacy

Posthumous fame

Following his first exhibitions in the late 1880s, Van Gogh's fame grew steadily among colleagues, art critics, dealers, and collectors.[183] After his death, memorial exhibitions were mounted in Brussels, Paris, The Hague, and Antwerp. In the early 20th century, there were retrospectives in Paris (1901 and 1905) and Amsterdam (1905), and important group exhibitions in Cologne (1912), New York (1913), and Berlin (1914).[184] These had a noticeable impact on later generations of artists.[185] By the mid-20th century, Van Gogh was seen as one of the greatest and most recognizable painters in history.[186][187] In 2007, a group of Dutch historians compiled the "Canon of Dutch History" to be taught in schools, and included Van Gogh as one of the fifty topics of the canon, alongside other national icons such as Rembrandt and De Stijl.

Together with those of Pablo Picasso, Van Gogh's works are among the world's most expensive paintings ever sold, based on data from auctions and private sales. Those sold for over US$100 million (today's equivalent) include Portrait of Dr. Gachet,[188] Portrait of Joseph Roulin, and Irises. A Wheatfield with Cypresses was sold in 1993 for US$57 million, a spectacularly high price at the time, and his Self Portrait with Bandaged Ear was sold privately in the late 1990s for an estimated US$80/$90 million.[189]

Influence

Vincent was childless and in his final letter to Theo, said that he viewed his paintings as his progeny. The historian Simon Schama said that Vincent "did have a child of course, Expressionism, and many, many heirs." Schama mentioned other artists who have adapted elements of Van Gogh's style, including Willem de Kooning, Howard Hodgkin and Jackson Pollock.[190] The Abstract Expressionism of the 1940s and 1950s is seen as in part inspired from Van Gogh's broad, gestural brush strokes. In the words of art critic Sue Hubbard: "At the beginning of the twentieth century Van Gogh gave the Expressionists a new painterly language that enabled them to go beyond surface appearance and penetrate deeper essential truths. It is no coincidence that at this very moment Freud was mining the depths of that essentially modern domain – the subconscious. This beautiful and intelligent exhibition places Van Gogh where he firmly belongs; as the trailblazer of modern art."[191]

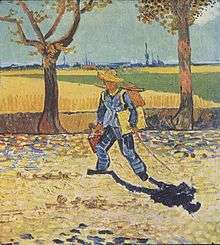

In 1947, Antonin Artaud, who also suffered from mental disorders, was invited by the art dealer Pierre Loeb to write on Van Gogh as a great retrospective of his works opened at the Orangerie in Paris.[192] This led to the book Van Gogh le suicidé de la société (Van Gogh, The Man Suicided by Society), in which Artaud argued that Van Gogh's psychological condition was to be understood as a superior lucidity misunderstood by his contemporaries.[193] In 1957, Francis Bacon based a series of paintings on reproductions of Van Gogh's The Painter on the Road to Tarascon, the original of which was destroyed during World War II. Bacon was inspired by both an image he described as "haunting", and by Van Gogh himself, whom he regarded as an alienated outsider, a position which resonated with him. Bacon identified with Van Gogh's theories of art and quoted lines written in a letter to Theo: "[R]eal painters do not paint things as they are ... [T]hey paint them as they themselves feel them to be."[194]

Footnotes

- ↑ The pronunciation of "Van Gogh" varies in both English and Dutch. Especially in British English it is /ˌvæn ˈɡɒx/ or sometimes /ˌvæn ˈɡɒf/. US dictionaries list /ˌvæn ˈɡoʊ/, with a silent gh, as the most common pronunciation. In the dialect of Holland, it is [ˈvɪnsɛnt fɑŋˈxɔx], with a voiceless V. He grew up in Brabant (although his parents were not born there), and used Brabant dialect in his writing; it is therefore likely that he pronounced his name with a Brabant accent: [vɑɲˈʝɔç], with a voiced V and palatalised G and gh. In France, where much of his work was produced, it is [vɑ̃ ɡɔɡə]

- ↑ It has been suggested that being given the same name as his dead elder brother might have had a deep psychological impact on the young artist, and that elements of his art, such as the portrayal of pairs of male figures, can be traced back to this. See Lubin (1972), 82–84.

- ↑ "...he would not eat meat, only a little morsel on Sundays, and then only after being urged by our landlady for a long time. Four potatoes with a suspicion of gravy and a mouthful of vegetables constituted his whole dinner" – from a letter to Frederik van Eeden, to help him with preparation for his article on Van Gogh in De Nieuwe Gids, Issue 1, December 1890. Quoted in Van Gogh: A Self-Portrait; Letters Revealing His Life as a Painter. W. H. Auden, New York Graphic Society, Greenwich, CT. (1961), 37–39

- ↑ Letter 129, April 1879, and Letter 132. Van Gogh lodged in Wasmes at 22 rue de Wilson with Jean-Baptiste Denis, a breeder or grower (cultivateur, in the French original) according to Letter 553b. In the recollections of his nephew Jean Richez, gathered by Wilkie (in the 1970s!), 72–8. Denis and his wife Esther were running a bakery, and Richez admits that the only source of his knowledge is Aunt Esther.

- ↑ There are different views as to this period; Jan Hulsker (1990) opts for a return to the Borinage and then back to Etten in this period; Dorn, in: Ges7kó (2006), 48 & note 12 supports this view

- ↑ see Jan Hulsker's speech The Borinage Episode and the Misrepresentation of Vincent van Gogh, Van Gogh Symposium, 10–11 May 1990. In Erickson (1998), 67–68

- ↑ Johannes de Looyer, Karel van Engeland, Hendricus Dekkers, and Piet van Hoorn all as old men recalled being paid 5, 10 or 50 cents per nest, depending on the type of bird. See Theo's son's Webexhibits.org

- ↑ The girl was Gordina de Groot, who died in 1927; she claimed the child's father was not Van Gogh, but a relative.

- ↑ Vincent's doctor was Hubertus Amadeus Cavenaile. Wilkie, 143–46

- ↑ Arnold, 77. The direct evidence for syphilis is thin, coming solely from interviews with the grandson of the doctor; see Tralbaut (1981), 177–78, and for a review of the evidence overall see Naifeh; Smith 477 n. 199

- ↑ According to Doiteau & Leroy, the diagonal cut removed the lobe and probably a little more.

- ↑ Gauguin, who had spent the night in a nearby hotel, arrived independently at the same time

- ↑ They continued to correspond and in 1890 Gauguin proposed they form an artist studio in Antwerp. See Pickvance (1986),62

References

- 1 2 Veltkamp, Paul. "Pronunciation of the Name "Van Gogh"". vggallery.com. Archived from the original on 22 September 2015.

- ↑ Hughes (1990), 144

- 1 2 Pickvance (1986), 129

- ↑ Tralbaut (1981), 39

- 1 2 Pomerans (1996), ix

- ↑ "Van Gogh: The Letters", vangoghletters.org; retrieved 7 October 2009.

- ↑ Van Gogh's letters, Unabridged and Annotated, webexhibits.org; retrieved 25 June 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 Hughes (1990), 143

- ↑ Pomerans (1996), i–xxvi

- ↑ Pomerans (1997), xiii

- ↑ Vincent Van Gogh Biography, Quotes & Paintings, The Art History Archive; retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ↑ Pomerans (1997), pg. 1

- ↑ Erickson (1998), 9

- ↑ Van Gogh-Bonger, Johanna. "Memoir of Vincent van Gogh". Van Gogh's Letters. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ↑ Tralbaut (1981), 24

- ↑ Tralbaut (1981), 25–35

- ↑ Hulsker (1984), 8–9

- ↑ Letter 347, Vincent to Theo, 18 December 1883. Van Gogh's Letters at webexhibits.org; retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ↑ Letter 7 Vincent to Theo, 5 May 1873. Van Gogh's Letters. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ↑ Tralbaut (1981), 35–47

- ↑ Letter from Vincent to Theo, August 1876. Van Gogh's Letters. Retrieved 16 January 2016

- ↑ Tralbaut (1981), 47–56.

- ↑ Callow (1990), 54

- ↑ See the recollections gathered in Dordrecht by M. J. Brusse, Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant, 26 May and 2 June 1914.

- ↑ McQuillan (1989), 26

- ↑ Erickson (1998), 23

- ↑ Hulsker (1990), 60–62, 73

- ↑ Letter from mother to Theo, 7 August 1879 Van Gogh's Letters, and Callow, work cited, 72

- ↑ Letter 158 Vincent to Theo, 18 November 1881. Van Gogh's Letters; retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ↑ Letter 134, Van Gogh's Letters, 20 August 1880 from Cuesmes

- ↑ Tralbaut (1981) 67–71

- ↑ Van Gogh Museum official website; accessed 20 November 2014. Archived 14 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Erickson (1998), 5

- ↑ Letter 153 Vincent to Theo, 3 November 1881

- ↑ "179". vangoghletters.org.

- ↑ Letter 161 Vincent to Theo, 23 November 1881

- ↑ Letter 164 Vincent to Theo, from Etten c.21 December 1881, describing the visit in more detail

- ↑ Letter Letter 193 from Vincent to Theo, The Hague, 14 May 1882.

- ↑ "Uncle Stricker", as Van Gogh refers to him in letters to Theo.

- ↑ Gayford (2006), 130–1

- ↑ Pomerans (1997), 112

- ↑ Letter 166 Vincent to Theo, 29 December 1881

- ↑ "Letter 194: To Theo van Gogh. The Hague, Thursday, 29 December 1881". Vincent van Gogh: The Letters. Van Gogh Museum. Note 2. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

At Christmas I had a rather violent argument with Pa ...

- ↑ "Letter 196". Vincent van Gogh. The Letters. Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum.

- ↑ "Letter 219". Vincent van Gogh. The Letters. Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum.

- ↑ McQuillan (1989), 34

- ↑ Letter 206, Vincent to Theo, 8 June/9 June 1882

- ↑ Tralbaut (1981), 110

- ↑ Tralbaut (1981), 96–103

- ↑ Callow (1990), 116; cites the work of Hulsker; Callow (1990), 123–124

- ↑ "Letter 224". Vincent van Gogh. The Letters. Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum.

- ↑ Callow (1990), 117,116; citing the research of Jan Hulsker; the two dead children were born in 1874 and 1879.

- 1 2 Tralbaut (1981), 107

- ↑ Callow (1990), 132; Tralbaut (1981), 102–104, 112

- ↑ Arnold, 38

- ↑ Tralbaut (1981), 113

- ↑ Wilkie, 185

- ↑ Tralbaut (1981),101–107

- 1 2 Tralbaut (1981), 111–22

- ↑ Vincent's nephew noted some reminiscences of local residents in 1949, including the description of the speed of his drawing

- ↑ Tralbaut (1981), 154

- ↑ McQuillan (1989), 127

- ↑ Vincent Van Gogh and Gordina de Groot, vangoghaventure.com; accessed 20 November 2014.

- ↑ Hulsker (1980) 196–205

- ↑ Tralbaut (1981), 123–160

- ↑ Callow (1990), 181

- ↑ Callow (1990), 184

- ↑ Hammacher (1985), 84

- ↑ Callow (1990), 253

- ↑ Van der Wolk (1987), 104–105

- ↑ Tralbaut (1981), 173

- ↑ Tralbaut (1981) 187–192

- ↑ Pickvance (1984), 38–39

- ↑ Tralbaut (1981), 216

- ↑ Letter 626a. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ↑ Van Gogh et Monticelli. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ↑ Turner, J. (2000), 314

- ↑ Pickvance (1986), 62–63

- ↑ Tralbaut (1981), 212–13

- ↑ "Glossary term: Pointillism", National Gallery London. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- ↑ "Glossary term: Complimentary colours", National Gallery, London. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- ↑ D. Druick & P. Zegers, Van Gogh and Gauguin: The Studio of the South, Thames & Hudson, 2001. 81; Gayford, (2006), 50

- ↑ Hulsker (1990), 256

- ↑ Letter 510 Vincent to Theo, 15 July 1888. Letter 544a. Vincent to Paul Gauguin, 3 October 1888.

- 1 2 Hughes, 144

- ↑ "Letters of Vincent van Gogh." Penguin, 1998. 348. ISBN 0-14-044674-5

- ↑ Nemeczek, Alfred (1999), 59–61.

- ↑ Gayford (2006), 16

- ↑ Callow (1990), 219

- ↑ Pickvance (1984), 175–76

- ↑ Tralbaut (1981), 266

- 1 2 Pomerans (1997), 356, 360

- ↑ "Fishing Boats on the Beach at Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, 1888". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–11; retrieved 18 May 2011. Archived 26 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Hulsker (1980), 356

- ↑ Pickvance (1984), 168–169;206

- ↑ Letter 534; Gayford (2006), 18

- ↑ Letter 537; Nemeczek, 61

- 1 2 See Dorn (1990)

- ↑ Pickvance (1984), 234–35

- ↑ Hulsker (1980), 374–6

- ↑ "Letter 719 to Theo van Gogh. Arles, Sunday, 11 or Monday, 12 November 1888". Vincent van Gogh: The Letters. Van Gogh Museum. 1v:3.

I've been working on two canvases.

A reminiscence of our garden at Etten with cabbages, cypresses, dahlias and figures ...Gauguin gives me courage to imagine, and the things of the imagination do indeed take on a more mysterious character. - ↑ Gayford (2006), 61

- ↑ Pickvance (1984), 195

- ↑ Gayford (2007), 274–77

- ↑ Sweetman (1990), 1

- ↑ Tralbaut (1981), 258

- ↑ Naifeh; Smith (2011), 702

- ↑ Gayford (2007), 277

- ↑ Hulsker, 380–82

- ↑ Bailey, Martin. "Van Gogh's Own Words After Cutting His Ear Recorded in Paris Newspaper. The Art Newspaper

- ↑ Naifeh; Smith 707-8

- 1 2 3 4 "Concordance, lists, bibliography: Documentation". Vincent van Gogh: The Letters. Van Gogh Museum.

- ↑ Naifeh; Smith (2011), 488–89/209–10

- ↑ Jules Breton and Realism, Van Gogh Museum Archived 26 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Pickvance (1984), 102–103

- ↑ Pickvance (1986), 154–157

- ↑ Tralbaut (1981), 286

- ↑ Hulsker (1990), 434

- 1 2 Gayford, 284

- ↑ Pickvance (1986), 239–42

- ↑ Tralbaut (1981), 265–273

- ↑ Hughes (1990), 145

- ↑ Callow (1990), 246

- ↑ "To Theo van Gogh. Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, Tuesday, 29 April 1890.". Vincent van Gogh: The Letters. Vincent van Gogh Museum. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- 1 2 Hulsker (1990), 390, 404

- ↑ Tralbaut (1981), 287

- ↑ Pickvance (1986) 175–177

- 1 2 Hulsker (1990), 440

- ↑ Aurier, G. Albert. "The Isolated Ones: Vincent van Gogh", January 1890. vggallery.com. Retrieved 25 June 2009

- ↑ Rewald (1978), 346–347; 348–350

- ↑ Tralbaut (1981), 293

- ↑ Kleiner, Carolyn (24 July 2000). "Van Gogh's vanishing act". Mysteries of History (U.S. News & World Report). Archived from the original on 31 January 2011. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ↑ Letter 648 Vincent to Theo, 10 July 1890

- ↑ "Letter 863". Vincent van Gogh: The Letters. Van Gogh Museum. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ↑ Rosenblum (1975), 98–100

- 1 2 Pickvance (1986), 270–271

- ↑ Hulsker (1980), 480–483. Wheat Field with Crows is work number 2117 of 2125

- ↑ Walther 2000, p. 74.

- ↑ Hughes (2002), 8

- 1 2 Sweetman (1990), 342–343

- ↑ Metzger and Walther (1993), 669

- ↑ Hulsker (1980), 480–483

- ↑ Pomerans (1997), 509

- ↑ "Letter from Emile Bernard to Albert". Van Gogh's Letters; retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ↑ Hayden, Deborah . POX, Genius, Madness and the Mysteries of Syphilis. Basic Books, 2003. 152. ISBN 0-465-02881-0

- ↑ van der Veen, Wouter; Knapp, Peter (2010). Van Gogh in Auvers: His Last Days. Monacelli Press. pp. 260–264. ISBN 978-1-58093-301-8.

- ↑ "La tombe de Vincent Van Gogh – Auvers-sur-Oise, France". Groundspeak. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- ↑ Sweetman (1990), 367

- ↑ Vincent van Gogh, "Letter to Theo van Gogh, written c. 10 July 1890 in Auvers-sur-Oise", translated by Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, edited by Robert Harrison, letter number 649; retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ↑ Rosenblum (1975), 100

- ↑ Blumer, Dietrich. American Journal of Psychiatry (2002)

- ↑ Van Heugten (1996), 246–51

- ↑ Artists working in Black & White, i.e., for illustrated papers like The Graphic or Illustrated London News were among Van Gogh's favorites. See Pickvance (1974/75)

- ↑ See Dorn, Keyes & alt. (2000)

- 1 2 See Dorn, Schröder & Sillevis, ed. (1996)

- ↑ See Welsh-Ovcharov & Cachin (1988)

- 1 2 Hulsker (1980), 385

- ↑ Pickvance (1986), 131

- ↑ "Musée d'Orsay: Vincent van Gogh Self-Portrait". Musée d'Orsay. 4 February 2009.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Irish and World Art: "art of self-portrait"; retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ↑ Pickvance, R. "Van Gogh in Arles". New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1984. 131. ISBN 0-87099-375-5

- ↑ Cohen, Ben. "A Tale of Two Ears", Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. June 2003. vol. 96. issue 6; retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ↑ Van Gogh Myths; The ear in the mirror. Letter to the New York Times, 17 September 1989; retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ↑ Self Portraits, Van Gogh Gallery; retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ↑ Metzger and Walther (1993), 653

- 1 2 Cleveland Museum of Art (2007). Monet to Dalí: Impressionist and Modern Masterworks from the Cleveland Museum of Art. Cleveland, OH: Cleveland Museum of Art. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-940717-89-3.

- ↑ "La Mousmé". Postimpressionism. National Gallery of Art. 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2011Additional information about the painting is found in the audio clip.

- ↑ Pickvance (1986), 132–133

- ↑ Pickvance (1986), 101; 189–191

- ↑ Pickvance (1984), 175–176

- ↑ Letter 595 Vincent to Theo, 17 or 18 June 1889

- ↑ Pickvance (1984),45–53

- ↑ Fell (1997), 32

- ↑ "Letter 573" Vincent to Theo. 22 or 23 January 1889

- ↑ Pickvance (1986), 80–81; 184–87

- 1 2 "Sunflowers 1888." National Gallery, London; retrieved 12 September 2009.

- 1 2 Pickvance (1984), 177

- ↑ Hulsker (1980), 390–94

- ↑ Edwards, Cliff. Van Gogh and God: A Creative Spiritual Quest. Loyola University Press, 1989, 115; ISBN 0-8294-0621-2

- ↑ Letter 649

- ↑ Hulsker (1990), 478–479

- ↑ Hulsker (1990).

- ↑ John Rewald, Studies in Post-Impressionism, The Posthumous Fate of Vincent van Gogh 1890–1970, 244–54, published by Harry N. Abrams (1986); ISBN 0-8109-1632-0.

- ↑ See Dorn, Leeman & alt. (1990)

- ↑ Rewald, John. "The posthumous fate of Vincent van Gogh 1890–1970", Museumjournaal, August–September 1970, Rewald (1986), 248

- ↑ "Vincent van Gogh The Dutch Master of Modern Art has his Greatest American Show," Life Magazine, 10 October 1949, 82–87.

- ↑ "Biography". National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. Archived from the original on 17 April 2006. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ↑ Andrew Decker, "The Silent Boom", Artnet.com. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ↑ G. Fernández, "The Most Expensive Paintings ever sold", TheArtWolf.com; retrieved 14 September 2011

- ↑ Schama, Simon. "Wheatfield with Crows". Simon Schama's Power of Art (2006 documentary), from 59:20

- ↑ Hubbard, Sue. Vincent Van Gogh and Expressionism, suehubbard.com; retrieved 3 July 2010. Archived 6 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Isabelle Cahn (dir.), Van Gogh/Artaud. Le suicidé de la société, Paris: Musée d'Orsay/Skira, 2014.

- ↑ Van Gogh, Artaud. The suicide of society. Musée d'Orsay. Retrieved 2 January 2015. See the Paris exhibition dedicated to the links between Van Gogh and Artaud, "Van Gogh/Artaud. Le suicidé de la société", which ran from March until July 2014 at the Musée d'Orsay, and resulted in the exhibition catalogue Isabelle Cahn (dir.), Van Gogh/Artaud. Le suicidé de la société, Paris: Musée d'Orsay/Skira, 2014.

- ↑ Farr, Dennis, Michael Peppiatt & Sally Yard. Francis Bacon: A Retrospective. Harry N. Abrams (1999). 112. ISBN 0-8109-2925-2

Bibliography

General and biographical

- Bernard, Bruce. Vincent by Himself. London: Little, Brown Book Group, 2004. ISBN 978-0-3167-2802-7

- Callow, Philip. Vincent van Gogh: A Life. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1990. ISBN 978-1-5666-3134-1

- Erickson, Kathleen Powers. At Eternity's Gate: The Spiritual Vision of Vincent van Gogh, 1998. ISBN 0-8028-4978-4

- Gayford, Martin. The Yellow House: Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Nine Turbulent Weeks in Arles. London: Penguin, 2006. ISBN 978-0-6709-1497-5

- Grossvogel, David I. Behind the Van Gogh Forgeries: A Memoir by David I. Grossvogel. San Jose: Author's Choice Press, 2001. ISBN 0-595-17717-4

- Hammacher, A.M. Vincent van Gogh: Genius and Disaster. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1985. ISBN 0-8109-8067-3

- Havlicek, William J. Van Gogh's Untold Journey. Amsterdam: Creative Storytellers 2010. ISBN 978-0-9824872-1-1

- Hughes, Robert. Nothing If Not Critical. London: The Harvill Press, 1990. ISBN 0-14-016524-X

- Hulsker, Jan. Vincent and Theo van Gogh; A dual biography. Ann Arbor: Fuller Publications, 1990. ISBN 0-940537-05-2

- Hulsker, J. The Complete Van Gogh. Oxford: Phaidon, 1980. ISBN 0-7148-2028-8

- Hughes, Robert. The Portable Van Gogh. New York: Universe, 2002. ISBN 978-0-7893-0803-0

- Lubin, Albert J. Stranger on the Earth: A Psychological Biography of Vincent van Gogh. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1972. ISBN 0-03-091352-7

- McQuillan, Melissa. Van Gogh. London: Thames and Hudson, 1989. ISBN 1-86046-859-4

- Naifeh, Steven; Gregory White, Smith. Van Gogh: the Life. New York: Random House, 2011. ISBN 978-0-375-50748-9

- Nemeczek, Alfred. Van Gogh in Arles. Prestel Verlag, 1999. ISBN 3-7913-2230-3

- Pomerans, Arnold. The Letters of Vincent van Gogh. London: Penguin Classics, 1997. ISBN 0-14-044674-5

- Petrucelli, Alan W. Morbid Curiosity: The Disturbing Demises of the Famous and Infamous. Perigee Trade, 2009. ISBN 0-399-53527-6

- Rewald, John. Post-Impressionism: From van Gogh to Gauguin. London: Secker & Warburg, 1978. ISBN 0-436-41151-2

- Rewald, John. Studies in Post-Impressionism. New York: Abrams, 1986. ISBN 0-8109-1632-0

- Sund, Judy. Van Gogh. London: Phaidon, 2002. ISBN 0-7148-4084-X

- Sweetman, David. Van Gogh: His Life and His Art. New York: Touchstone, 1990. ISBN 0-671-74338-4

- Tralbaut, Marc Edo. Vincent van Gogh, le mal aimé. Edita, Lausanne (French) & Macmillan, London (1969) (English); reissued by Macmillan, 1974. ISBN 0-933516-31-2

- Van Heugten, Sjraar. Van Gogh The Master Draughtsman. London: Thames and Hudson, 2005. ISBN 978-0-5002-3825-7

- Walther, Ingo; Metzger, Rainer. Van Gogh: the Complete Paintings. New York: Taschen, 1997. ISBN 3-8228-8265-8

- Walther, Ingo. Van Gogh. Cologne:Taschen, 2000.ISBN 978-3-8228-6322-0

- Wilkie, Kenneth. "The Van Gogh File: The Myth and the Man." Souvenir Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-2856-3691-0

Art historical

- Boime, Albert. Vincent van Gogh: Die Sternennacht-Die Geschichte des Stoffes und der Stoff der Geschichte, Frankfurt/Mainz: Fischer, 1989. ISBN 3-596-23953-2

- Cachin, Françoise & Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov. Van Gogh à Paris (exh. cat. Musée d'Orsay, Paris 1988), Paris: RMN, 1988. ISBN 2-7118-2159-5.

- Dorn, Roland: Décoration: Vincent van Gogh's Werkreihe für das Gelbe Haus in Arles. Zürich & New York: Olms Verlag, Hildesheim, 1990. ISBN 3-487-09098-8.

- Dorn, Roland, Fred Leeman & alt. Vincent van Gogh and Early Modern Art, 1890–1914 (exh. cat). Essen & Amsterdam (1990); ISBN 3-923641-33-8 (English); ISBN 3-923641-31-1 (German); ISBN 90-6630-247-X (Dutch)

- Dorn, Roland, George Keyesm & alt. Van Gogh Face to Face: The Portraits (exh. cat). Detroit, Boston & Philadelphia, 2000–01, Thames & Hudson, London & New York, 2000. ISBN 0-89558-153-1

- Druick, Douglas, Pieter Zegers & alt. Van Gogh and Gauguin-The Studio of the South (exh. cat). Chicago & Amsterdam 2001–02, Thames & Hudson, London & New York, 2001. ISBN 0-500-51054-7

- Fell, Derek. The Impressionist Garden, London: Frances Lincoln, 1997. ISBN 0-7112-1148-5

- Geskó, Judit (ed) Van Gogh in Budapest. Budapest: Vince Books, 2006. ISBN 978-963-7063-34-3 (English); ISBN 963-7063-33-1 (Hungarian)

- Ives, Colta, Stein, Susan Alyson & alt. Vincent van Gogh-The Drawings. New Haven: YUP, 2005; ISBN 0-300-10720-X

- Kōdera, Tsukasa. Vincent van Gogh-Christianity versus Nature. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 1990; ISBN 90-272-5333-1

- Pickvance, Ronald. English Influences on Vincent van Gogh (exh. cat). University of Nottingham & alt. 1974/75). London: Arts Council, 1974.

- Pickvance, R. Van Gogh in Arles (exh. cat. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: Abrams, 1984; ISBN 0-87099-375-5

- Pickvance, R. Van Gogh In Saint-Rémy and Auvers (exh. cat. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: Abrams, 1986; ISBN 0-87099-477-8

- Orton, Fred and Griselda Pollock. "Rooted in the Earth: A Van Gogh Primer", in: Avant-Gardes and Partisans Reviewed. London: Redwood Books, 1996; ISBN 0-7190-4398-0

- Rosenblum, Robert (1975), Modern Painting and the Northern Romantic Tradition: Friedrich to Rothko, New York: Harper & Row; ISBN 0-06-430057-9

- Schaefer, Iris, Caroline von Saint-George & Katja Lewerentz: Painting Light. The hidden techniques of the Impressionists. Milan: Skira, 2008; ISBN 88-6130-609-8

- Turner, J. (2000). From Monet to Cézanne: late 19th-century French artists. Grove Art. New York: St Martin's Press; ISBN 0-312-22971-2

- Van der Wolk, Johannes: De schetsboeken van Vincent van Gogh, Meulenhoff/Landshoff, Amsterdam (1986); ISBN 90-290-8154-6; translated to English: The Seven Sketchbooks of Vincent van Gogh: a facsimile edition, New York: Abrams, 1987.

- Van Heugten, Sjraar. "Radiographic images of Vincent van Gogh's paintings in the collection of the Van Gogh Museum", Van Gogh Museum Journal. 1995. pp. 63–85; ISBN 90-400-9796-8

- Van Heugten, S. Vincent van Gogh Drawings, vol. 1, Bussum: V+K, 1996. ISBN 90-6611-501-7 (Dutch edition).

- Van Uitert, Evert, et al. Van Gogh in Brabant: Paintings and drawings from Etten and Nuenen (English). Zwolle: Waanders, Zwolle (1987); ISBN 90-6630-104-X

- Van Uitert, Evert, Louis van Tilborgh and Sjraar van Heughten. Paintings (1990). (Centenary exhibition catalogue) Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum Vincent van Gogh; accessed 20 November 2014.

External links

- Vincent van Gogh Gallery: The complete works and letters of Vincent van Gogh

- The complete letters of Van Gogh (translated into English and annotated)

- Works by Vincent van Gogh at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Vincent van Gogh at Internet Archive

- Works by Vincent van Gogh at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|