Vigenère cipher

The Vigenère cipher is a method of encrypting alphabetic text by using a series of different Caesar ciphers based on the letters of a keyword. It is a simple form of polyalphabetic substitution.[1][2]

The Vigenère (French pronunciation: [viʒnɛːʁ]) cipher has been reinvented many times. The method was originally described by Giovan Battista Bellaso in his 1553 book La cifra del. Sig. Giovan Battista Bellaso; however, the scheme was later misattributed to Blaise de Vigenère in the 19th century, and is now widely known as the "Vigenère cipher".

Though the cipher is easy to understand and implement, for three centuries it resisted all attempts to break it; this earned it the description le chiffre indéchiffrable (French for 'the indecipherable cipher'). Many people have tried to implement encryption schemes that are essentially Vigenère ciphers.[3] Friedrich Kasiski was the first to publish a general method of deciphering a Vigenère cipher.

History

The first well documented description of a polyalphabetic cipher was formulated by Leon Battista Alberti around 1467 and used a metal cipher disc to switch between cipher alphabets. Alberti's system only switched alphabets after several words, and switches were indicated by writing the letter of the corresponding alphabet in the ciphertext. Later, in 1508, Johannes Trithemius, in his work Poligraphia, invented the tabula recta, a critical component of the Vigenère cipher. The Trithemius cipher, however, only provided a progressive, rigid and predictable system for switching between cipher alphabets.

What is now known as the Vigenère cipher was originally described by Giovan Battista Bellaso in his 1553 book La cifra del. Sig. Giovan Battista Bellaso. He built upon the tabula recta of Trithemius, but added a repeating "countersign" (a key) to switch cipher alphabets every letter. Whereas Alberti and Trithemius used a fixed pattern of substitutions, Bellaso's scheme meant the pattern of substitutions could be easily changed simply by selecting a new key. Keys were typically single words or short phrases, known to both parties in advance, or transmitted "out of band" along with the message. Bellaso's method thus required strong security for only the key. As it is relatively easy to secure a short key phrase, say by a previous private conversation, Bellaso's system was considerably more secure.

Blaise de Vigenère published his description of a similar but stronger autokey cipher before the court of Henry III of France, in 1586. Later, in the 19th century, the invention of Bellaso's cipher was misattributed to Vigenère. David Kahn in his book The Codebreakers lamented the misattribution by saying that history had "ignored this important contribution and instead named a regressive and elementary cipher for him [Vigenère] though he had nothing to do with it".[4]

The Vigenère cipher gained a reputation for being exceptionally strong. Noted author and mathematician Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (Lewis Carroll) called the Vigenère cipher unbreakable in his 1868 piece "The Alphabet Cipher" in a children's magazine. In 1917, Scientific American described the Vigenère cipher as "impossible of translation".[5] This reputation was not deserved. Charles Babbage is known to have broken a variant of the cipher as early as 1854; however, he didn't publish his work.[6] Kasiski entirely broke the cipher and published the technique in the 19th century. Even before this, though, some skilled cryptanalysts could occasionally break the cipher in the 16th century.[4]

The Vigenère cipher is simple enough to be a field cipher if it is used in conjunction with cipher disks.[7] The Confederate States of America, for example, used a brass cipher disk to implement the Vigenère cipher during the American Civil War. The Confederacy's messages were far from secret and the Union regularly cracked their messages. Throughout the war, the Confederate leadership primarily relied upon three key phrases, "Manchester Bluff", "Complete Victory" and, as the war came to a close, "Come Retribution".[8]

Gilbert Vernam tried to repair the broken cipher (creating the Vernam-Vigenère cipher in 1918), but, no matter what he did, the cipher was still vulnerable to cryptanalysis. Vernam's work, however, eventually led to the one-time pad, a provably unbreakable cipher.

Description

In a Caesar cipher, each letter of the alphabet is shifted along some number of places; for example, in a Caesar cipher of shift 3, A would become D, B would become E, Y would become B and so on. The Vigenère cipher consists of several Caesar ciphers in sequence with different shift values.

To encrypt, a table of alphabets can be used, termed a tabula recta, Vigenère square, or Vigenère table. It consists of the alphabet written out 26 times in different rows, each alphabet shifted cyclically to the left compared to the previous alphabet, corresponding to the 26 possible Caesar ciphers. At different points in the encryption process, the cipher uses a different alphabet from one of the rows. The alphabet used at each point depends on a repeating keyword.

For example, suppose that the plaintext to be encrypted is:

- ATTACKATDAWN

The person sending the message chooses a keyword and repeats it until it matches the length of the plaintext, for example, the keyword "LEMON":

- LEMONLEMONLE

Each row starts with a key letter. The remainder of the row holds the letters A to Z (in shifted order). Although there are 26 key rows shown, you will only use as many keys (different alphabets) as there are unique letters in the key string, here just 5 keys, {L, E, M, O, N}. For successive letters of the message, we are going to take successive letters of the key string, and encipher each message letter using its corresponding key row. Choose the next letter of the key, go along that row to find the column heading that matches the message character; the letter at the intersection of [key-row, msg-col] is the enciphered letter.

For example, the first letter of the plaintext, A, is paired with L, the first letter of the key. So use row L and column A of the Vigenère square, namely L. Similarly, for the second letter of the plaintext, the second letter of the key is used; the letter at row E and column T is X. The rest of the plaintext is enciphered in a similar fashion:

| Plaintext: | ATTACKATDAWN |

| Key: | LEMONLEMONLE |

| Ciphertext: | LXFOPVEFRNHR |

Decryption is performed by going to the row in the table corresponding to the key, finding the position of the ciphertext letter in this row, and then using the column's label as the plaintext. For example, in row L (from LEMON), the ciphertext L appears in column A, which is the first plaintext letter. Next we go to row E (from LEMON), locate the ciphertext X which is found in column T, thus T is the second plaintext letter.

Algebraic description

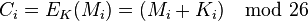

Vigenère can also be viewed algebraically. If the letters A–Z are taken to be the numbers 0–25, and addition is performed modulo 26, then Vigenère encryption  using the key

using the key  can be written,

can be written,

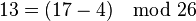

and decryption  using the key

using the key  ,

,

,

,

where  is the message,

is the message,  is the ciphertext and

is the ciphertext and  is the key obtained by repeating the keyword

is the key obtained by repeating the keyword  times, where

times, where  is the keyword length.

is the keyword length.

Thus using the previous example, to encrypt  with key letter

with key letter  the calculation would result in

the calculation would result in  .

.

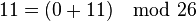

Therefore, to decrypt  with key letter

with key letter  the calculation would result in

the calculation would result in  .

.

Cryptanalysis

The idea behind the Vigenère cipher, like all polyalphabetic ciphers, is to disguise plaintext letter frequencies, which interferes with a straightforward application of frequency analysis. For instance, if P is the most frequent letter in a ciphertext whose plaintext is in English, one might suspect that P corresponds to E, because E is the most frequently used letter in English. However, using the Vigenère cipher, E can be enciphered as different ciphertext letters at different points in the message, thus defeating simple frequency analysis.

The primary weakness of the Vigenère cipher is the repeating nature of its key. If a cryptanalyst correctly guesses the key's length, then the cipher text can be treated as interwoven Caesar ciphers, which individually are easily broken. The Kasiski examination and Friedman test can help determine the key length.

Kasiski examination

- For more details on this topic, see Kasiski examination.

In 1863 Friedrich Kasiski was the first to publish a successful general attack on the Vigenère cipher. Earlier attacks relied on knowledge of the plaintext, or use of a recognizable word as a key. Kasiski's method had no such dependencies. Kasiski was the first to publish an account of the attack, but it is clear that there were others who were aware of it. In 1854, Charles Babbage was goaded into breaking the Vigenère cipher when John Hall Brock Thwaites submitted a "new" cipher to the Journal of the Society of the Arts. When Babbage showed that Thwaites' cipher was essentially just another recreation of the Vigenère cipher, Thwaites challenged Babbage to break his cipher encoded twice, with keys of different length. Babbage succeeded in decrypting a sample, which turned out to be the poem "The Vision of Sin", by Alfred Tennyson, encrypted according to the keyword "Emily", the first name of Tennyson's wife. Babbage never explained the method he used. Studies of Babbage's notes reveal that he had used the method later published by Kasiski, and suggest that he had been using the method as early as 1846.[9]

The Kasiski examination, also called the Kasiski test, takes advantage of the fact that repeated words may, by chance, sometimes be encrypted using the same key letters, leading to repeated groups in the ciphertext. For example, Consider the following encryption using the keyword ABCD:

Key: ABCDABCDABCDABCDABCDABCDABCD Plaintext: CRYPTOISSHORTFORCRYPTOGRAPHY Ciphertext: CSASTPKVSIQUTGQUCSASTPIUAQJB

There is an easily seen repetition in the ciphertext, and the Kasiski test will be effective. Here the distance between the repetitions of CSASTP is 16. Assuming that the repeated segments represent the same plaintext segments, this implies that the key is 16, 8, 4, 2, or 1 characters long. (All factors of the distance are possible key lengths—a key of length one is just a simple caesar cipher, where cryptanalysis is much easier.) Since key lengths 2 and 1 are unrealistically short, one only needs to try lengths 16, 8, or 4. Longer messages make the test more accurate because they usually contain more repeated ciphertext segments. The following ciphertext has two segments that are repeated:

Ciphertext: VHVSSPQUCEMRVBVBBBVHVSURQGIBDUGRNICJQUCERVUAXSSR

The distance between the repetitions of VHVS is 18. Assuming that the repeated segments represent the same plaintext segments, this implies that the key is 18, 9, 6, 3, 2, or 1 characters long. The distance between the repetitions of QUCE is 30 characters. This means that the key length could be 30, 15, 10, 6, 5, 3, 2, or 1 characters long. By taking the intersection of these sets one could safely conclude that the most likely key length is 6, since 3, 2, and 1 are unrealistically short.

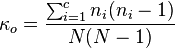

Friedman test

The Friedman test (sometimes known as the kappa test) was invented during the 1920s by William F. Friedman. Friedman used the index of coincidence, which measures the unevenness of the cipher letter frequencies to break the cipher. By knowing the probability  that any two randomly chosen source-language letters are the same (around 0.067 for monocase English) and the probability of a coincidence for a uniform random selection from the alphabet

that any two randomly chosen source-language letters are the same (around 0.067 for monocase English) and the probability of a coincidence for a uniform random selection from the alphabet  (1/26 = 0.0385 for English), the key length can be estimated as:

(1/26 = 0.0385 for English), the key length can be estimated as:

from the observed coincidence rate

where c is the size of the alphabet (26 for English), N is the length of the text, and n1 through nc are the observed ciphertext letter frequencies, as integers.

This is, however, only an approximation whose accuracy increases with the size of the text. It would in practice be necessary to try various key lengths close to the estimate.[10] A better approach for repeating-key ciphers is to copy the ciphertext into rows of a matrix having as many columns as an assumed key length, then compute the average index of coincidence with each column considered separately; when this is done for each possible key length, the highest average I.C. then corresponds to the most likely key length.[11] Such tests may be supplemented by information from the Kasiski examination.

Frequency analysis

Once the length of the key is known, the ciphertext can be rewritten into that many columns, with each column corresponding to a single letter of the key. Each column consists of plaintext that has been encrypted by a single Caesar cipher; the Caesar key (shift) is just the letter of the Vigenère key that was used for that column. Using methods similar to those used to break the Caesar cipher, the letters in the ciphertext can be discovered.

An improvement to the Kasiski examination, known as Kerckhoffs' method, matches each column's letter frequencies to shifted plaintext frequencies to discover the key letter (Caesar shift) for that column. Once every letter in the key is known, the cryptanalyst can simply decrypt the ciphertext and reveal the plaintext.[12] Kerckhoffs' method is not applicable when the Vigenère table has been scrambled, rather than using normal alphabetic sequences, although Kasiski examination and coincidence tests can still be used to determine key length in that case.

Key elimination

The Vigenère cipher with normal alphabets essentially uses modulo arithmetic, which is commutative. So if the key length is known (or guessed) then subtracting the cipher text from itself, offset by the key length, will produce the plain text encrypted with itself. If any "probable word" in the plain text is known or can be guessed, then its self-encryption can be recognized, allowing recovery of the key by subtracting the known plaintext from the cipher text. Key elimination is especially useful against short messages.

Variants

The running key variant of the Vigenère cipher was also considered unbreakable at one time. This version uses as the key a block of text as long as the plaintext. Since the key is as long as the message the Friedman and Kasiski tests no longer work (the key is not repeated). In 1920, Friedman was the first to discover this variant's weaknesses. The problem with the running key Vigenère cipher is that the cryptanalyst has statistical information about the key (assuming that the block of text is in a known language) and that information will be reflected in the ciphertext.

If using a key which is truly random, is at least as long as the encrypted message and is used only once, the Vigenère cipher is theoretically unbreakable. However, in this case it is the key, not the cipher, which provides cryptographic strength and such systems are properly referred to collectively as one-time pad systems, irrespective of which ciphers are employed.

Vigenère actually invented a stronger cipher: an autokey cipher. The name "Vigenère cipher" became associated with a simpler polyalphabetic cipher instead. In fact, the two ciphers were often confused, and both were sometimes called "le chiffre indéchiffrable". Babbage actually broke the much stronger autokey cipher, while Kasiski is generally credited with the first published solution to the fixed-key polyalphabetic ciphers.

A simple variant is to encrypt using the Vigenère decryption method, and decrypt using Vigenère encryption. This method is sometimes referred to as "Variant Beaufort". This is different from the Beaufort cipher, created by Francis Beaufort, which nonetheless is similar to Vigenère but uses a slightly modified enciphering mechanism and tableau. The Beaufort cipher is a reciprocal cipher.

Despite the Vigenère cipher's apparent strength it never became widely used throughout Europe. The Gronsfeld cipher is a variant created by Count Gronsfeld which is identical to the Vigenère cipher, except that it uses just 10 different cipher alphabets (corresponding to the digits 0 to 9). The Gronsfeld cipher is strengthened because its key is not a word, but it is weakened because it has just 10 cipher alphabets. Gronsfeld's cipher did become widely used throughout Germany and Europe, despite its weaknesses.

See also

- Roger Frontenac (Nostradamus quatrain decryptor, 1950)

References

Citations

- ↑ Bruen, Aiden A. & Forcinito, Mario A. (2011). Cryptography, Information Theory, and Error-Correction: A Handbook for the 21st Century. John Wiley & Sons. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-118-03138-4.

- ↑ Martin, Keith M. (2012). Everyday Cryptography. Oxford University Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-19-162588-6.

- ↑ Smith, Laurence D. (1943). "Substitution Ciphers". Cryptography the Science of Secret Writing: The Science of Secret Writing. Dover Publications. p. 81. ISBN 0-486-20247-X.

- 1 2 David, Kahn (1999). "On the Origin of a Species". The Codebreakers: The Story of Secret Writing. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-83130-9.

- ↑ Knudsen, Lars R. (1998). "Block Ciphers—a survey". In Bart Preneel and Vincent Rijmen. State of the Art in Applied Cryptography: Course on Computer Security and Industrial Cryptograph Leuven Belgium, June 1997 Revised Lectures. Berlin ; London: Springer. p. 29. ISBN 3-540-65474-7.

- ↑ Singh, Simon (1999). "Chapter 2: Le Chiffre Indéchiffrable". The Code Book. Anchor Books, Random House. pp. 63–78. ISBN 0-385-49532-3.

- ↑ Codes, Ciphers, & Codebreaking (The Rise Of Field Ciphers)

- ↑ David, Kahn (1999). "Crises of the Union". The Codebreakers: The Story of Secret Writing. Simon & Schuster. pp. 217–221. ISBN 0-684-83130-9.

- ↑ Franksen, O. I. (1985) Mr. Babbage's Secret: The Tale of a Cipher—and APL. Prentice Hall.

- ↑ Henk C.A. van Tilborg, ed. (2005). Encyclopedia of Cryptography and Security (First ed.). Springer. p. 115. ISBN 0-387-23473-X.

- ↑ Mountjoy, Marjorie (1963). "The Bar Statistics". NSA Technical Journal VII (2,4). Published in two parts.

- ↑ "Lab exercise: Vigenere, RSA, DES, and Authentication Protocols" (PDF). CS 415: Computer and Network Security. Retrieved 2006-11-10.

Sources

- Beutelspacher, Albrecht (1994). "Chapter 2". Cryptology. translation from German by J. Chris Fisher. Washington, DC: Mathematical Association of America. pp. 27–41. ISBN 0-883-85504-6.

- Singh, Simon (1999). "Chapter 2: Le Chiffre Indéchiffrable". The Code Book. Anchor Book, Random House. ISBN 0-385-49532-3.

- Gaines, Helen Fouche (1939). "The Gronsfeld, Porta and Beaufort Ciphers". Cryptanalysis a Study of Ciphers and Their Solutions. Dover Publications. pp. 117–126. ISBN 0-486-20097-3.

- Mendelsohn, Charles J (1940). "Blaise De Vigenere and The 'Chiffre Carre'". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 82 (2).

External links

- Articles

- History of the cipher from Cryptologia

- Basic Cryptanalysis at H2G2

- Lecture Notes on Classical Cryptology including an explanation and derivation of the Friedman Test

- aolnews.com at the Wayback Machine (archived June 24, 2011)

- Programming

- Hacking Secret Ciphers with Python Chapter 19, The Vigenère Cipher, Chapter 21, Hacking the Vigenère Cipher, with Python source code.

- Sharky's Online Vigenere Cipher – Encode and decode messages, using a known key, within a Web browser (JavaScript)

- PyGenere: an online tool for automatically deciphering Vigenère-encoded texts (6 languages supported)

- Vigenère Cipher encryption and decryption program (browser version, English only)

- Crypt::Vigenere – a CPAN module implementing the Vigenère cipher

- Breaking the indecipherable cipher: Perl code to decipher Vigenère text, with the source in the shape of Babbage's head

- Vigenère in BASH

- Java Vigenere applet with source code (GNU GPL)

- Vigenere Cipher in Java

- Vijner 974 Encryption Tool in C# (Vigenere Algorithm)

- Vigenère Cipher encryption tool – Browser

- Vigenère Cipher encryption tool – Google Chrome extension

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||