Victorian dress reform

Victorian dress reform was an objective of the Victorian dress reform movement (also known as the rational dress movement) of the middle and late Victorian era, comprising various reformers who proposed, designed, and wore clothing considered more practical and comfortable than the fashions of the time.

Dress reformists were largely middle class women involved in the first wave of feminism in the United States and in Britain, from the 1850s through the 1890s. The movement emerged in the Progressive Era along with calls for temperance, women's education, suffrage and moral purity. Dress reform called for emancipation from the "dictates of fashion", expressed a desire to “cover the limbs as well as the torso adequately,” and promoted rational dress.[1] The movement had its greatest success in the reform of women's undergarments, which could be modified without exposing the wearer to social ridicule. Dress reformers were also influential in persuading women to adopt simplified garments for athletic activities such as bicycling or swimming. The movement was much less concerned with men's clothing, although it initiated the widespread adoption of knitted wool union suits or long johns.

Some proponents of the movement established dress reform parlors, or storefronts, where women could buy sewing patterns for the newfangled garments, or buy them directly.[2][3]

Criticisms of tightlacing

Fashions in the 1850s through 1880s accented large crinolines, cumbersome bustles and padded busts with tiny waists laced into ‘steam-moulded corsetry’.[4] ‘Tight-lacing’ formed two sides of the argument around dress reform: for dress reformists, corsets were a dangerous moral ‘evil’, promoting promiscuous views of female bodies and superficial dalliance into fashion whims. The obvious health risks, including damaged and rearranged internal organs, compromised fertility; weakness and general depletion of health were also blamed on excessive corsetry. Eventually, the reformers' critique of the corset joined a throng of voices clamoring against tightlacing, which became gradually more common and extreme as the 19th century progressed. Preachers inveighed against tightlacing, doctors counseled patients against it and journalists wrote articles condemning the vanity and frivolity of women who would sacrifice their health for the sake of fashion. Whereas for many corseting was accepted as necessary for beauty, health, and an upright military-style posture, dress reformists viewed tightlacing as vain and, especially at the height of the era of Victorian morality, a sign of moral indecency.

American women active in the anti-slavery and temperance movements, with experience in public speaking and political agitation demanded sensible clothing that would not restrict their movement.[5] While support for fashionable dress contested that corsets maintained an upright, ‘good figure’, as a necessary physical structure for moral and well-ordered society, these dress reformists contested that women’s fashions were not only physically detrimental, but “the results of male conspiracy to make women subservient by cultivating them in slave psychology.”[6][7] A change in fashions could change the whole position of women, allowing for greater social mobility, independence from men and marriage, the ability to work for wages, as well as physical movement and comfort.[8]

Despite these protests, little changed in restrictive fashion and undergarments by 1900. The Edwardian Era featured a decadence of fashion following the ideal shape of the Gibson Girl, a corseted, big-bosomed ideal of femininity and sophistication.[9] Corset styles had altered slightly from the shorter-waisted, bustled 1880s vogue, but they still constricted the waist, forced the hips back with a pointed front waistline, thrust the bosom forward and curved the back into an exaggerated ‘S’ shape. Skirts weighed from the hips, high collars chaffed the neck, and the whole costume prevented natural movement, harmed internal organs and threatened childbearing potential.[10] Invariably, the ideal image of feminine attractiveness that a Victorian woman saw around her (in fashion plates, advertisements, etc.) was of a wasp-waisted, firmly-corseted lady.

'Emancipation Waists' and undergarment reform

Dress reformers promoted the emancipation waist, or liberty bodice, as a replacement for the corset. The emancipation bodice was a tight sleeveless vest, buttoning up the front, with rows of buttons along the bottom to which could be attached petticoats and a skirt. The entire torso would support the weight of the petticoats and skirt, not just the waist (since the undesirability of hanging the entire weight of full skirts and petticoats from a constricted waist — rather than hanging the garments from the shoulders — was another point often discussed by dress reformers).[11] The bodices had to be fitted by a dressmaker; patterns could be ordered through the mail. Physician Alice Bunker Stockham railed against the corset and said of the pregnancy corset, "The Best pregnancy corset is no corset at all."[12] The "emancipation union under flannel" was first sold in America in 1868. It combined a waist (shirt) and drawers (leggings) in the form we now know as the union suit. While first designed for women, the union suit was also adopted by men. Indeed, it is still sold and worn today, by both men and women, as winter underclothing.

In 1878, a German professor named Gustav Jaeger published a book claiming that only clothing made of animal hair, such as wool, promoted health. A British accountant named Lewis Tomalin translated the book, then opened a shop selling Dr Jaeger’s Sanitary Woollen System, including knitted wool union suits. These were soon called "Jaegers"; they were widely popular.

It is not clear how many women, in either the Americas or on the Continent, wore these so-called "reform" bodices. However, contemporary portrait photography, fashion literature, and surviving examples of the undergarments themselves, all suggest that the corset was almost universal as daily wear by women and young ladies (and numerous fashionable men) throughout much of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The bloomer suit

Most famous product of the dress reform era is the bloomers suit. In 1851, a New England temperance activist named Elizabeth Smith Miller (Libby Miller) adopted what she considered a more rational costume: loose trousers gathered at the ankles, like the trousers worn by Middle Eastern and Central Asian women, topped by a short dress or skirt and vest. She displayed her new clothing to temperance activist and suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who found it sensible and becoming, and adopted it immediately. In this garb, she visited yet another activist, Amelia Bloomer, the editor of the temperance magazine The Lily. Bloomer not only wore the costume, she promoted it enthusiastically in her magazine. More women wore the fashion and were promptly dubbed "Bloomers". The Bloomers put up a valiant fight for a few years, but were subjected to ridicule in the press[13][14] and harassment on the street.[15] The more conservative of society protested that women had ‘lost the mystery and attractiveness as they discarded their flowing robes.” [16]

Amelia Bloomer herself dropped the fashion in 1859, saying that a new invention, the crinoline, was a sufficient reform that she could return to conventional dress. The bloomer costume died — temporarily. It was to return much later (in a different form), as a women's athletic costume in the 1890s and early 1900s.

Aesthetic Dress movement

In the 1870s, a largely English movement led by Mary Eliza Haweis sought dress reform to enhance and celebrate the natural shape of the body, preferring the looser lines of the medieval and renaissance eras. A historic nostalgia for more forgiving fashions, the aesthetic dress movement critiqued fashionable dress for its immovable shapes, and sought the ‘fashioning and adorning of a robe’ as tastefully complementary to the natural body.[17]

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and other artistic reformers objected to the elaborately trimmed confections of Victorian fashion with their unnatural silhouette based on a rigid corset and hoops as both ugly and dishonest. Their wives and models adopted a revival style based on romanticised medieval influences such as puffed juliette sleeves and trailing skirts. These styles were made in the soft colors of vegetable dyes, ornamented with hand embroidery in the art needlework style, featured silks, oriental designs, muted colors, natural and frizzed hair and lacked definitive waist emphasis.[18]

The style spread as an "anti-fashion" called Artistic dress in the 1860s in literary and artistic circles, died back in the 1870s, and reemerged as Aesthetic dress in the 1880s, where the emphasis was not so much on honesty and purity as sensuality and languor.

Eventual shifts in fashion

Although the Victorian dress reform movement itself failed to enact widespread change in women’s fashion, social, political and cultural shifts into the 1920s brought forth an organic relaxation of dress standards.[19]

With new opportunities for women's college, the national suffrage amendment of 1920 and women’s increased public career options during and after World War I, fashion and undergarment structures relaxed, along with the improved social standing of women.[20] Embodying the New Woman idea, women donned masculine-inspired fashions including simple tailored skirt suits, ties and starched blouses.[21] By the 1920s, male-style garments for casual and sporting activities were less socially condemned. New fashions required lighter undergarments, shorter skirts, looser bodices, trousers, and praised slender ‘boyish’ figures.[22] As Lady Duff Gordon remarked, in the 1920s “women took off their corsets, reduced their clothing to the minimum tolerated by conventions and wore clothes which wrapped round them rather than fitted.” [23]

Although forms of corsets, girdles and bras were worn well into the 1960s, as Riegel states, “Feminine emancipation had brought greater dress reform than the most visionary of the early feminists had advocated.”[24]

Girl athletes and working women

In the 19th century, poor women were known to wear corsets "boned" with rope, rather than steel or bone, to facilitate work in the field.

-

Approx. second half of 1880s poster showing Annie Oakley wearing short-skirted attire

-

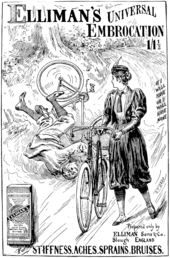

An 1897 ad, showing a relatively early example of an ordinary non-sea-bathing woman in public view in unskirted garments (to ride a bicycle)

-

1895 Punch satire on wearing a bicycle suit despite lacking a bicycle

-

Wigan "pit brow lasses" scandalized by wearing trousers for dangerous work in coal mines. They wore skirts over their trousers, rolled up to the waist to keep them out of the way.

See also

References

- ↑ “Fashion, Emancipation, Reform and the Rational Undergarment” Deborah Jean Waugh ‘Dress’ Vol 4, 1978"

- ↑ Bryan, C.W. (1887). Good Housekeeping, Vols. 5-6.

- ↑ "Downtown Walk". Boston Women's Heritage Trail.

- ↑ Dress and Morality by Aileen Ribeiro, (Homes and Meier Publishers Inc: New York. 1986) p. 134

- ↑ "Woman's dress, a question of the day". Early Canadiana Online. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ↑ Dress and Morality by Aileen Ribeiro, (Homes and Meier Publishers Inc: New York. 1986) p. 134

- ↑ “Women's Clothes and Women's Right,” Robert E. Riegel, American Quarterly, 15 (1963): 390

- ↑ “Women's Clothes and Women's Right,” Robert E. Riegel, American Quarterly, 15 (1963): 391

- ↑ “Women's Clothes and Women's Right,” Robert E. Riegel, American Quarterly, 15 (1963): 400

- ↑ Dress and Morality by Aileen Ribeiro, (Homes and Meier Publishers Inc: New York. 1986) p. 134

- ↑ "Woman's dress, a question of the day". Early Canadiana Online. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ↑ Alice Bunker Stockham. Tokology 1898.

- ↑ New York Times, October 5, 1851: 'Bloomerism in London:...One journal hints very ill-naturedly that the new dress is best adapted for a particular class of "ladies", who, poor things, having a deal of "street-walking", would find the Bloomer costume quite a blessing..'

- ↑ The Times, Wednesday, Aug 20, 1851; pg. 5; Issue 20885; col A: ‘DEBUT OF THE “BLOOMER” COSTUME IN BELFAST:...Three ladies... made their appearance in full “Bloomer” costume...Others, and these most numerous, expressed an opinion the reverse of complimentary to the rank and character of the ladies, identifying them with persons whose overdressed gaiety of appearance in public stamps the class to which they belong.’

- ↑ The Times, Thursday, Aug 28, 1851; pg. 7; Issue 20892; col B: (A report from the ‘’Caledonian Mercury’’ of two women appearing in Edinburgh in reformed dress)‘BLOOMERISM IN EDINBURGH:...The singular spectacle thus presented attracted considerable attention even in the retired quarter of the town where it was witnessed, and comments, characterized by freedom more than politeness, were now and again made by urchins who followed the unblushing Bloomers...we learn that the ladies are Americans;...’

- ↑ “Women's Clothes and Women's Right,” Robert E. Riegel, American Quarterly, 15 (1963):393

- ↑ Dress and Morality by Aileen Ribeiro, (Homes and Meier Publishers Inc: New York. 1986): 139

- ↑ The Visual History of Costume. Aileen Ribeiro and Valerie Cumming, (Costume & Fashion Press, New York, 1989):188

- ↑ “Women's Clothes and Women's Right,” Robert E. Riegel, American Quarterly, 15 (1963): 399

- ↑ “Women's Clothes and Women's Rights,” Robert E. Riegel, American Quarterly, 15 (1963): 400

- ↑ Dress and Morality by Aileen Ribeiro, (Homes and Meier Publishers Inc: New York. 1986) p. 143

- ↑ “Women's Clothes and Women's Rights,” Robert E. Riegel, American Quarterly, 15 (1963): 399

- ↑ (“Fashion, Emancipation, Reform and the Rational Undergarment” Deborah Jean Waugh ‘Dress’ Vol 4, 1978: 238 Quote by Lady Duff Gordon (Lucile) from “Discretions and Indiscretions”)

- ↑ “Women's Clothes and Women's Right,” Robert E. Riegel, American Quarterly, 15 (1963): 399