Variable speed wind turbine

Original models of wind turbines were fixed speed turbines; that is, the rotor speed was a constant for all wind speeds. The tip-speed ratio for a wind turbine is given by the following formula:

where  is the rotor speed (in radians per second),

is the rotor speed (in radians per second),  is the length of a blade, and

is the length of a blade, and  is the wind speed. That is to say, for a fixed-speed wind turbine, the value of the tip-speed ratio is only changed by wind speed variations. In reference to a

is the wind speed. That is to say, for a fixed-speed wind turbine, the value of the tip-speed ratio is only changed by wind speed variations. In reference to a  -

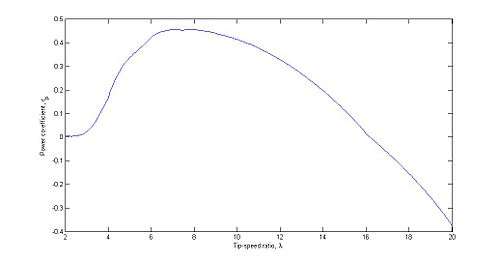

- graph, which illustrates the relationship between Tip-speed ratio and efficiency, it is evident that only one value of

graph, which illustrates the relationship between Tip-speed ratio and efficiency, it is evident that only one value of  yields the highest efficiency. That is, the fixed speed wind turbine is not operating at peak efficiency across a range of wind speeds. This was a motivator for the development of variable speed wind turbines.

yields the highest efficiency. That is, the fixed speed wind turbine is not operating at peak efficiency across a range of wind speeds. This was a motivator for the development of variable speed wind turbines.

Background

All wind turbines that generated electricity were variable speed before 1939.[1]

All grid-connected wind turbines, from the first one in 1939 until the development of variable-speed grid-connected wind turbines in the 1970s, were fixed-speed wind turbines. As of 2003, nearly all grid-connected wind turbines operate at exactly constant speed (synchronous generators) or within a few percent of constant speed (induction generators).[1]

Cp-λ curves

Below is an illustration of the  curve for a typical wind turbine.

curve for a typical wind turbine.

Maximum efficiency occurs at one tip-speed ratio only. Since tip-speed ratio is given by the aforementioned expression, variable speed wind turbines can operate at maximum efficiency over all wind speeds (ideally).

Torque Rotor-speed diagrams

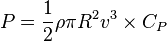

For a wind turbine, the power harvested is given by the following formula:

where  is the power,

is the power,  is the density of the air,

is the density of the air,  is the length of the blade,

is the length of the blade,  is the velocity of the wind, and

is the velocity of the wind, and  is the power co-efficient for the wind turbine. The power co-efficient is a representation of how much of the available power in the wind is captured by the wind turbine.

is the power co-efficient for the wind turbine. The power co-efficient is a representation of how much of the available power in the wind is captured by the wind turbine.

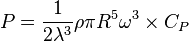

The torque,  , on the blades is given by the ratio of the power extracted to the rotor speed,

, on the blades is given by the ratio of the power extracted to the rotor speed,  :

:

The rotor speed can be related to the wind speed,  , through the tip-speed ratio,

, through the tip-speed ratio,  :

:

Thus we can get the following expressions for torque and power:

and

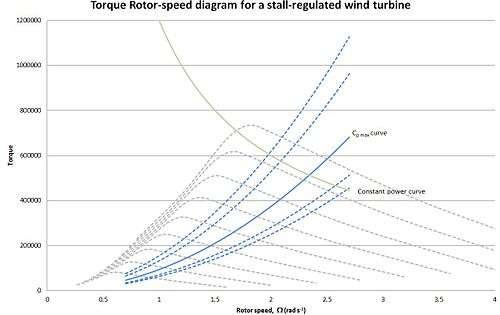

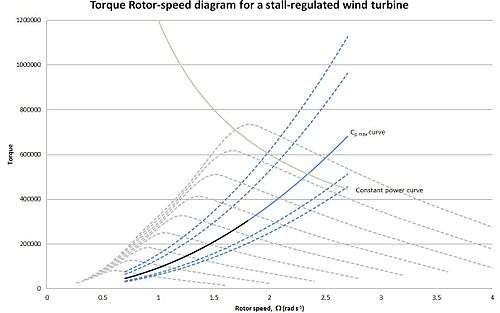

From the above equation, we can construct a torque- rotor speed diagram for a wind turbine. This consists of multiple curves: a constant power curve which plots the relationship between torque and rotor speed for constant power (green curve); constant wind speed curves, which plot the relationship between torque and rotor speed for constant wind speeds (dashed grey curves); and constant efficiency curves, which plot the relationship between torque and rotor speed for constant efficiencies,  .[2] This diagram is presented below:

.[2] This diagram is presented below:

Notes

Green curve: Plot of power = rated power

Grey curve: Wind speed,  , is held constant

, is held constant

Blue curve: Constant

Blade forces

For further details, see Blade Element Momentum Theory

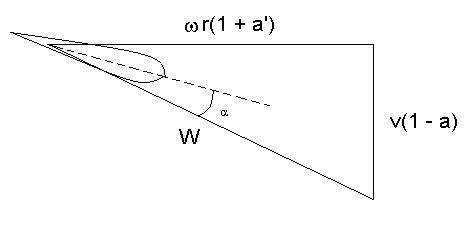

Consider the following figure:

This is the depiction of the apparent wind speed, as seen by a blade (left of figure). The apparent wind speed is influenced by both the free-stream velocity of the air, and the rotor speed. From this figure, we can see that both the angle  and the apparent wind speed

and the apparent wind speed  are functions of the rotor speed,

are functions of the rotor speed,  . By extension, the lift and drag forces will also be functions of

. By extension, the lift and drag forces will also be functions of  . This means that the axial and tangential forces that act on the blade vary with rotor speed. The force in the axial direction is given by the following formula:

. This means that the axial and tangential forces that act on the blade vary with rotor speed. The force in the axial direction is given by the following formula:

Operating strategies for variable speed wind turbines

Stall regulated

As discussed earlier, a wind turbine would ideally operate at its maximum efficiency for below rated power. Once rated power has been hit, the power is limited. This is for two reasons: ratings on the drivetrain equipment, such as the generator; and second to reduce the loads on the blades. An operating strategy for a wind turbine can thus be divided into a sub-rated-power component, and a rated-power component.

Below rated power

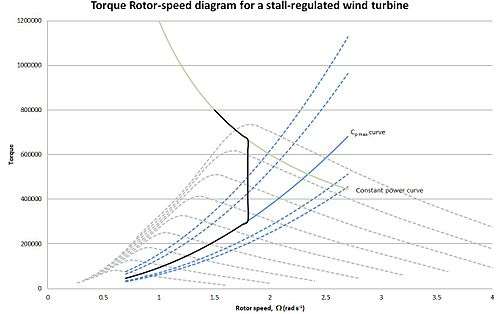

Below rated power, the wind turbine will ideally operate in such a way that  . On a Torque-rotor speed diagram, this looks as follows:

. On a Torque-rotor speed diagram, this looks as follows:

where the black line represents the initial section of the operating strategy for a variable speed stall-regulated wind turbine. Ideally, we would want to stay on the maximum efficiency curve until rated power is hit. However, as the rotor speed increases, the noise levels increase. To counter this, the rotor speed is not allowed to increase above a certain value. This is illustrated in the figure below:

Rated power and above

Once the wind speed has reached a certain level, called rated wind speed, the turbine should not be able to produce any greater levels of power for higher wind speeds. A stall-regulated variable speed wind turbine has no pitching mechanism. However, the rotor speed is variable. The rotor speed can either be increased or decreased by an appropriately designed controller. In reference to the figure illustrated in the blade forces section, it is evident that the angle between the apparent wind speed and the plane of rotation is dependent upon the rotor speed. This angle is termed the angle of attack.

The lift and drag co-efficients for an airfoil are related to the angle of attack. Specifically, for high angles of attack, an airfoil stalls. That is, the drag substantially increases. The lift and drag forces influence the power production of a wind turbine. This can be seen from an analysis of the forces acting on a blade as air interacts with the blade (see the following link). Thus, forcing the airfoil to stall can result in power limiting.

So it can be established that if the angle of attack needs to be increased to limit the power production of the wind turbine, the rotor speed must be reduced. Again, this can be seen from the figure in the blade forces section. It can also be seen from considering the torque-rotor speed diagram. In reference to the above torque-rotor speed diagram, by reducing the rotor speed at high wind speeds, the turbine enters the stall region, thus bringing some limiting to the power output.

Pitch regulated

Pitch regulation allows the wind turbine to actively change the angle of attack of the air on the blades. This is preferred over a stall-regulated wind turbine as it enables far greater control of the power output.

Below rated power

Identical to the stall-regulated variable-speed wind turbine, the initial operating strategy is to operate on the  curve. However, due to constraints such as noise levels, this is not possible for the full range of sub-rated wind speeds. Below the rated wind speed, the following operating strategy is employed:

curve. However, due to constraints such as noise levels, this is not possible for the full range of sub-rated wind speeds. Below the rated wind speed, the following operating strategy is employed:

Above rated power

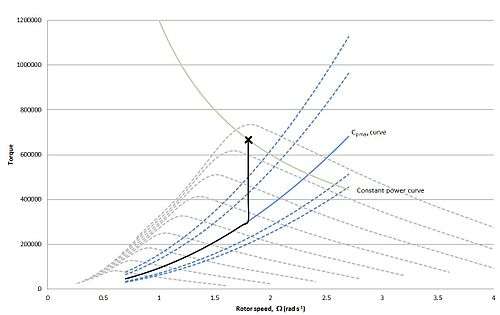

Above the rated wind speed, the pitching mechanism is employed. This allows a good level of control over the angle of attack, thus control over the torque. The previous torque rotor-speed diagrams are all plots when the pitch angle,  , is zero. A three dimensional plot can be produced which includes variations in pitch angle.

, is zero. A three dimensional plot can be produced which includes variations in pitch angle.

Ultimately, in the 2D plot, above rated wind speed, the turbine will operate at the point marked 'x' on the diagram below.

Gearboxes

A variable speed may or may not have a gearbox, depending on the manufacturer's desires. Wind turbines without gearboxes are called direct-drive wind turbines. An advantage of a gearbox is that generators are typically designed to have the rotor rotating at a high speed within the stator. Direct drive wind turbines do not exhibit this feature. A disadvantage of a gearbox is reliability and failure rates.[3]

An example of a wind turbine without a gearbox is the Enercon E82.[4]

Generators

For variable speed wind turbines, one of two types of generators can be used: a DFIG (doubly fed induction generator) or an FRC (fully rated converter).

A DFIG generator draws reactive power from the transmission system; this can increase the vulnerability of a transmission system in the event of a failure. A DFIG configuration will require the generator to be a wound rotor;[5] squirrel cage rotors cannot be used for such a configuration.

A fully rated converter can either be an induction generator or a permanent magnet generator. Unlike the DFIG, the FRC can employ a squirrel cage rotor in the generator; an example of this is the Siemens SWT 3.6-107, which is termed the industry workhorse.[6] An example of a permanent magnet generator is the Siemens SWT-2.3-113.[7] A disadvantage of a permanent magnet generator is the cost of materials that need to be included.[8]

Grid Connections

Consider a variable speed wind turbine with a permanent magnet synchronous generator. The generator produces AC electricity. The frequency of the AC voltage generated by the wind turbine is a function of the speed of the rotor within the generator:

where  is the rotor speed,

is the rotor speed,  is the number of poles in the generator, and

is the number of poles in the generator, and  is the frequency of the output Voltage. That is, as the wind speed varies, the rotor speed varies, and so the frequency of the Voltage varies. This form of electricity cannot be directly connected to a transmission system. Instead, it must be corrected such that its frequency is constant. For this, power converters are employed, which results in the de-coupling of the wind turbine from the transmission system. As more wind turbines are included in a national power system, the inertia is decreased. This means that the frequency of the transmission system is more strongly affected by the loss of a single generating unit.

is the frequency of the output Voltage. That is, as the wind speed varies, the rotor speed varies, and so the frequency of the Voltage varies. This form of electricity cannot be directly connected to a transmission system. Instead, it must be corrected such that its frequency is constant. For this, power converters are employed, which results in the de-coupling of the wind turbine from the transmission system. As more wind turbines are included in a national power system, the inertia is decreased. This means that the frequency of the transmission system is more strongly affected by the loss of a single generating unit.

Power converters

As already mentioned, the voltage generated by a variable speed wind turbine is non-grid compliant. In order to supply the transmission network with power from these turbines, the signal must be passed through a power converter, which ensures that the frequency of the voltage of the electricity being generated by the wind turbine is the frequency of the transmission system when it is transferred onto the transmission system. Power converters first convert the signal to DC, and then convert the DC signal to an AC signal. Techniques used include pulse width modulation

References

- 1 2 P. W. Carlin, A. S. Laxson, and E. B. Muljadi. "The History and State of the Art of Variable-Speed wind Turbine Technology". 2003. p. 130-131.

- ↑ http://www.springer.com/cda/content/document/cda_downloaddocument/9781846284922-c1.pdf?SGWID=0-0-45-436805-p172423327

- ↑ http://mragheb.com/Wind%20Power%20Gearbox%20Technologies.pdf

- ↑ http://www.enercon.de/en-en/64.htm

- ↑ http://www.4thintegrationconference.com/second/downloads/Anaya%20Trans%20Tutorial%20Talk.pdf

- ↑ http://www.energy.siemens.com/nl/pool/hq/power-generation/renewables/wind-power/wind%20turbines/E50001-W310-A103-V6-4A00_WS_SWT_3_6_107_US.pdf

- ↑ http://www.energy.siemens.com/us/pool/hq/power-generation/wind-power/E50001-W310-A174-X-4A00_WS_SWT-2.3-113_US.pdf

- ↑ http://www.rechargenews.com/wind/article1292870.ece