Vancouver Police Department

| Vancouver Police Department | |

|---|---|

| Common name | Vancouver Police |

| Abbreviation | VPD |

|

Heraldic badge of the VPD | |

|

Shoulder Flash of the Vancouver Police | |

| Motto |

Servamus We serve/We guard |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | May 10, 1886 |

| Employees | 1716 |

| Volunteers | Depending on CPC |

| Annual budget | $219,148,000 |

| Legal personality | Governmental: Government agency |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

| Operations jurisdiction* | City of Vancouver in the province of British Columbia, Canada |

| Size | 114.97 square kilometres (44.39 sq mi) |

| Population | 2,603,502 |

| Governing body | Vancouver Police Board |

| Constituting instrument | BC Police Act |

| General nature | |

| Operational structure | |

| Headquarters | 2120 Cambie Street |

| Police Constables | 1327[1] |

| Civilians | 389 |

| Elected officers responsible |

|

| Agency executive | Adam Palmer, Chief Constable |

| Boroughs |

List

|

| Facilities | |

| Commands |

5 Precincts 14 Transit Districts 9 Housing Police Service Areas |

| Police cars | 4,300 |

| Police boats | 12 |

| Helicopters | 4 |

| Horses | 77 |

| Dogs | 18 German Shepherds |

| Website | |

|

vancouver | |

| Footnotes | |

| * Divisional agency: Division of the country, over which the agency has usual operational jurisdiction. | |

The Vancouver Police Department (VPD) is the police force for the City of Vancouver in British Columbia, Canada. It is one of several police departments within the Metro Vancouver Area and is the second largest police force in the province after RCMP "E" Division.

VPD was the first Canadian municipal police force to hire a female officer and the first to start a marine squad.[2]

VPD, along with 11 other BC municipal police forces, seconds officers to the Combined Forces Special Enforcement Unit of British Columbia.

VPD now occupies the former Vancouver Organizing Committee for the 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games (VANOC) building at 3585 Graveley Street, which houses administrative and specialized investigation units.[3][4]

History

At the first meeting of Vancouver City Council, Vancouver's first police officer, Chief Constable John Stewart, was appointed on May 10, 1886.

On June 14, 1886, the morning after the Great Fire of 1886, Mayor McLean appointed Jackson Abray, V.W. Haywood, and John McLaren as special constables. With uniforms from Seattle and badges fashioned from American coins, this four man team became Vancouver's first police department based out of the City Hall tent at the foot of Carrall Street. These four were replaced in 1887 by special constables sent by the provincial government in Victoria for not keeping the peace during the anti-Asian unrest of that year. The strength of the force increased from four to fourteen as a result.

By 1904, the department had grown to 31 members and occupied a new police building at 200 Cordova Street. In 1912, Vancouver's first two women were taken on the force as matrons. With the amalgamation of Point Grey and South Vancouver with Vancouver in 1929, the department absorbed the two smaller police forces under the direction of Chief Constable W.J. Bingham, a former District Supervisor with the Metropolitan Police in London. By the 1940s the department had grown to 570 members.

In 1912, L.D. Harris and Minnie Miller were hired as the first two policewomen in Canada.

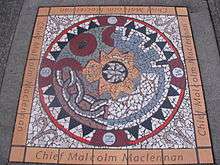

In 1917, Chief Constable McLennan, was killed in the line of duty in a shoot-out in Vancouver's East End. Responding to a call by a landlord attempting to evict a tenant, the police were met by gunfire. Along with McLennan, the shooter was killed in the battle, as was a nine-year-old boy in the vicinity at Georgia and Jackson streets, which is now marked by a mosaic memorial. A detective who lost an eye in the shootout, John Cameron, later became the chief constable of the New Westminster Police Department before taking the top job of the Vancouver force, which he occupied from 1933 to the end of 1934.

Another member of the force was killed in the line of duty in 1922. Twenty-three-year-old Constable Robert McBeath was shot by a man stopped for impaired driving. McBeath received the Victoria Cross for "most conspicuous bravery" at the Battle of Cambrai in France in the First World War. McBeath's killer, Fred Deal, was initially sentenced to death, but won an appeal reducing it to life in prison because he had been beaten while in custody. The Marine Squad's boat, the R.G. McBeath VC, was commissioned in 1995 and named in honour of McBeath.

Plans for a new police building at 312 Main Street began in 1953. The Oakridge police station opened in 1961.

A Police memorial at 325 Main St. is dedicated to the Vancouver Police Department members who gave their lives in the First and Second World Wars and listing the Vancouver Police Department members killed in the line of duty in Vancouver. [5]

In 1935 under Chief Constable W. W. Foster, the Vancouver Police Department was complemented with hundreds of special constables because of a waterfront strike led by communists, which culminated in the Battle of Ballantyne Pier, a riot that broke out when demonstrators attempted to march to the docks to confront strikebreakers. Also that year, nearly 2,000 unemployed men from the federal relief camps scattered throughout the province flocked to Vancouver to protest camp conditions. After two months of incessant demonstrations, the camp strikers left Vancouver and began the On-to-Ottawa Trek.

The Vancouver Police was at the centre of one of the biggest scandals in the city's history in 1955. Feeling frustrated that blatant police corruption was being ignored by the local media, a reporter for the Vancouver Daily Province switched to a Toronto-based tabloid, Flash. He wrote a sensational article alleging corruption at the highest levels of the police department in Vancouver, specifically, that a pay-off system had been implemented whereby gambling operations that paid the police were left alone and those that did not were harassed. After the Flash article appeared in Vancouver, the allegations could no longer be ignored, and a Royal Commission, the Tupper Commission, was struck to hold a public inquiry. Chief Constable Walter Mulligan fled to the United States, another officer from the upper ranks committed suicide, and still another attempted suicide rather than face the inquiry.[6] Other scandals and public inquiries plagued the force before and since this one, dubbed "The Mulligan Affair", but none were so dramatic. An earlier inquiry into corruption in 1928 was ambiguous in its conclusions as to the extent of the problem. The last major inquiry into policing in Vancouver focused largely on police accountability. Judge Wally Oppal (later provincial Attorney General), submitted the results of his report in 1994 in a four volume package entitled Closing the Gap: Policing and the Community.[7]

In 2009, the RCMP "E" Division joined forces with VPD to operate the Integrated National Security Enforcement Team (INSET)—Vancouver, operating out of VPD facilities instead of the INSET-BC Surrey operation base.[8]

Organization

The 1716 employees of the VPD [1] have been headed by Chief Constable Adam Palmer since May 6, 2015 following the retirement of Jim Chu. Three sections or units are assigned to the Office of the Chief Constable:[9]

- Chief's Executive Officer: Acting Inspector Mike Serr

- Planning, Research & Audit Section: Mr. Drazen Manojlovic

- Community and Public Affairs Section: Senior Director Paul Patterson

- Block Watch

- Community Policing Centres

- Diversity and Aboriginal Policing Section

- Victim Services Unit

Community Policing Centres

Organization

Community Policing Centres (CPCs), except Granville Downtown and Kitsilano Fairview CPCs, are run by registered societies. Granville Downtown CPC is under the direct control of the District 1 commander whereas Kitsilano Fairview is under District 4 commander.[10]

Budget

Each CPCs receives $108,200 annually from the VPD,[11] with the exception of two non-society based CPCs which has a combined budget of $140,000. The budget is delivered in four quarterly payments and they can be used towards staff salaries, CPC programs, costs from electricity, renting office space, etc.[12]

Operation

CPCs are run by volunteers on a day-to-day basis with the supervision from paid staffs. Each year, the VPD audits all the CPCs and then reports to the city council on budgeting.

Each CPC is assigned a Neighbourhood Police Officer (NPO) who provides resources and guidance for the operation of CPC.

Programs

Each CPC offers different programs based on budget and neighbourhood needs. For example:

- Taking non-emergency/lost and found property reports

- Project Griffin

- Working in conjunction with the Insurance Corporation of British Columbia for the Speed Watch program[13]

- Working in conjunction with the Insurance Corporation of British Columbia for the Stolen Auto Recovery program[14]

- Working in conjunction with the VPD for the Block Watch Program[15]

- Community Patrol (Foot/Bike)

- Bike Roadeo, program for young children in bike safety

- Outreach/Education programs

- Engraving

- Community cleanup

- Child Find[16]

- Citizen's Crime Watch

However, CPCs do not offer any of the following services:

- Taking emergency report

- Criminal Record Checks

- Law/bylaw Enforcement

- Legal/policing advice

- Victim Services

- Situations that requires police attendance/assistance

The rank and file are represented by the Vancouver Police Union.

Divisions

The force has three operating divisions:[17]

Operations

Led by Deputy Chief Constable Warren Lemcke.

- All patrols

- Mounted Squad

- Marine Squad

- Traffic Section

- Emergency & Operations Planning Section

- Emergency Planning Unit

- Operational Planning Unit

- Vancouver Traffic Authority (Special Municipal Constable with restricted Peace Officer status)

- Emergency Response Section

- Emergency Response Team

- Dog Squad

Investigations

Led by Deputy Chief Constable Doug LePard.

- Criminal Intelligence Section

- Gangs / Drugs Section

- Investigative Services

- Forensic Identification Unit

- Operations Investigative Section

- Crime Scene Investigation Unit

- Tactical Support Section

- Youth Services Section

Support Services

Led by Deputy Chief Constable Steve Rai.

- Communications Section

- Court & Detention Services Section

- Vancouver Jail Guard (Special Municipal Constable with Peace Officer status)

- Human Resources Section

- Facilities Section

- Financial Services Section

- Information Management Section

- Information Technology Section

- Professional Standards Section

- Recruiting and Training Section

Rank structure

- Chief of Police / Chief Constable (crown over three pips)

- Deputy Chief / Deputy Chief Constable (crown over two pips)

- Superintendent (crown over one pip)

- Inspector (Three Pips)

- Staff Sergeant (crown over three chevrons point down)

- Sergeant (three chevrons point down)

- Police Constable 1st Class / Detective

- Police Constable 2nd Class

- Police Constable 3rd Class

- Police Constable 4th Class (includes recruit constables)

- Special Municipal Constable (Traffic Authority/Jail Guard/Community Safety Personnel)

List of Chief Constables

- Adam Palmer 2015

- Jim Chu 2007–2015

- Jamie Graham 2002–2007

- Bruce Chambers

- Terry Blythe 1999–2002

- Raymond J. Canuel 1994–1997

- Bob Stewart

- Don Winterton

- Walter Mulligan 1947–1955 – charged with corruption and fled to Los Angeles, return to Canada 1963 and died in 1987.[18]

- John McLaren 1890–?

- John Stewart 1886–1890

Geography

The VPD is divided into four geographic districts:

- District 1: Downtown, Granville, West End & Coal Harbour

- District 2: Grandview-Woodland and Hastings-Sunrise

- Beat Enforcement Team: Downtown Eastside, Chinatown and Gastown

- District 3: Collingwood and South Vancouver

- District 4: Kerrisdale, Oakridge, Dunbar, West Point Grey, Kitsilano, Arbutus, Shaughnessy, Fairview, Musqueam and Marpole

Fleet

- Eurocopter EC120: air patrol operations shared with RCMP "E" Division

- Ford Crown Victoria Interceptors (Being phased out)

- Lenco BearCat APC: purchased approved

- Cambli International Thunder 1 ARV—delivered 2010 for SWAT use

- Ford Taurus Two unmarked Black Ford Interceptor Sedan (the demonstrators that were kept)

- Dodge Charger Police Pursuit (Replacement for Ford Crown Victoria)

- Ford Police Interceptor Utility Unmarked & marked supervisor vehicles

- Chevrolet Tahoe Unmarked SUVs

- Ford Fusion CSP/Special Investigations

- Ford F-350 ERT

- Ford Excursion ERT

See also

- Combined Forces Special Enforcement Unit of British Columbia

- E-Comm, 9-1-1 call and dispatch centre for Southwestern BC

- Project Griffin, crime prevention/reduction program launched in 2009

- RCMP "E" Division—Policing for surrounding areas (i.e. UBC, Burnaby, Surrey, etc.)

- Metro Vancouver Transit Police

References

- 1 2 VPD Organization

- ↑ THE VANCOUVER POLICE DEPARTMENT: 125 YEARS OF INNOVATION

- ↑ 3585 GRAVELEY STREET fact sheet

- ↑ Vancouver police leaving old headquarters

- ↑ "Vancouver Police memorial". National Inventory of Canadian Military Memorials. National Defence Canada. April 16, 2008. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- ↑ Macdonald, Ian; Betty O'Keefe (1997). The Mulligan Affair: Top Cop on the Take. Vancouver: Heritage House. ISBN 1-895811-45-7.

- ↑ Wally Oppal (1994). Closing the Gap: Policing and the Community.

- ↑ B.C. – Introducing INSET-Vancouver

- ↑ Chief Constable of the Vancouver Police Department

- ↑ VPD Community Policing

- ↑ 2011 VPD Preliminary Operating Budget and Capital Submission

- ↑ Community Policing Initiatives and Funding

- ↑ Speed Watch. ICBC. Retrieved on 2014-04-12.

- ↑ Stolen Auto Recovery Program. ICBC. Retrieved on 2014-04-12.

- ↑ http://www.city.vancouver.bc.ca/police/blockwatch/index.htm

- ↑ ChildFindBC.com. ChildFindBC.com (October 4, 2011). Retrieved on 2014-04-12.

- ↑ Organization of Vancouver Police Department

- ↑ http://vancouverhistory.ca/archives_mulligan.htm

- "Vancouver Police Department – History"

- Joe Swan, A Century of Service: The Vancouver Police 1886–1986. Vancouver: Vancouver Police Historical Society and Centennial Museum, 1986.

External links

Community Policing Centres websites

- District 1

- District 2

- District 3

- District 4