Pressure measurement

Many techniques have been developed for the measurement of pressure and vacuum. Instruments used to measure pressure are called pressure gauges or vacuum gauges.

A manometer is an instrument that uses a column of liquid to measure pressure, although the term is currently often used to mean any pressure measuring instrument.

A vacuum gauge is used to measure the pressure in a vacuum—which is further divided into two subcategories: high and low vacuum (and sometimes ultra-high vacuum). The applicable pressure ranges of many of the techniques used to measure vacuums have an overlap. Hence, by combining several different types of gauge, it is possible to measure system pressure continuously from 10 mbar down to 10−11 mbar.

Absolute, gauge and differential pressures - zero reference

Everyday pressure measurements, such as for tire pressure, are usually made relative to ambient air pressure. In other cases measurements are made relative to a vacuum or to some other specific reference. When distinguishing between these zero references, the following terms are used:

- Absolute pressure is zero-referenced against a perfect vacuum, using an absolute scale, so it is equal to gauge pressure plus atmospheric pressure.

- Gauge pressure is zero-referenced against ambient air pressure, so it is equal to absolute pressure minus atmospheric pressure. Negative signs are usually omitted. To distinguish a negative pressure, the value may be appended with the word "vacuum" or the gauge may be labeled a "vacuum gauge."

- Differential pressure is the difference in pressure between two points.

The zero reference in use is usually implied by context, and these words are added only when clarification is needed. Tire pressure and blood pressure are gauge pressures by convention, while atmospheric pressures, deep vacuum pressures, and altimeter pressures must be absolute.

For most working fluids where a fluid exists in a closed system, gauge pressure measurement prevails. Pressure instruments connected to the system will indicate pressures relative to the current atmospheric pressure. The situation changes when extreme vacuum pressures are measured; absolute pressures are typically used instead.

Differential pressures are commonly used in industrial process systems. Differential pressure gauges have two inlet ports, each connected to one of the volumes whose pressure is to be monitored. In effect, such a gauge performs the mathematical operation of subtraction through mechanical means, obviating the need for an operator or control system to watch two separate gauges and determine the difference in readings.

Moderate vacuum pressure readings can be ambiguous without the proper context, as they may represent absolute pressure or gauge pressure without a negative sign. Thus a vacuum of 26 inHg gauge is equivalent to an absolute pressure of 30 inHg (typical atmospheric pressure) − 26 inHg = 4 inHg.

Atmospheric pressure is typically about 100 kPa at sea level, but is variable with altitude and weather. If the absolute pressure of a fluid stays constant, the gauge pressure of the same fluid will vary as atmospheric pressure changes. For example, when a car drives up a mountain, the (gauge) tire pressure goes up because atmospheric pressure goes down. The absolute pressure in the tire is essentially unchanged.

Using atmospheric pressure as reference is usually signified by a g for gauge after the pressure unit, e.g. 70 psig, which means that the pressure measured is the total pressure minus atmospheric pressure. There are two types of gauge reference pressure: vented gauge (vg) and sealed gauge (sg).

A vented gauge pressure transmitter for example allows the outside air pressure to be exposed to the negative side of the pressure sensing diaphragm, via a vented cable or a hole on the side of the device, so that it always measures the pressure referred to ambient barometric pressure. Thus a vented gauge reference pressure sensor should always read zero pressure when the process pressure connection is held open to the air.

A sealed gauge reference is very similar except that atmospheric pressure is sealed on the negative side of the diaphragm. This is usually adopted on high pressure ranges such as hydraulics where atmospheric pressure changes will have a negligible effect on the accuracy of the reading, so venting is not necessary. This also allows some manufacturers to provide secondary pressure containment as an extra precaution for pressure equipment safety if the burst pressure of the primary pressure sensing diaphragm is exceeded.

There is another way of creating a sealed gauge reference and this is to seal a high vacuum on the reverse side of the sensing diaphragm. Then the output signal is offset so the pressure sensor reads close to zero when measuring atmospheric pressure.

A sealed gauge reference pressure transducer will never read exactly zero because atmospheric pressure is always changing and the reference in this case is fixed at 1 bar.

To produce an absolute pressure sensor the manufacturer will seal a high vacuum behind the sensing diaphragm. If the process pressure connection of an absolute pressure transmitter is open to the air, it will read the actual barometric pressure.

Units

| Pascal | Bar | Technical atmosphere | Standard atmosphere | Torr | Pounds per square inch | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Pa) | (bar) | (at) | (atm) | (Torr) | (psi) | |

| 1 Pa | ≡ 1 N/m2 | 10−5 | 1.0197×10−5 | 9.8692×10−6 | 7.5006×10−3 | 1.450377×10−4 |

| 1 bar | 105 | ≡ 100 kPa

≡ 106 dyn/cm2 |

1.0197 | 0.98692 | 750.06 | 14.50377 |

| 1 at | 9.80665×104 | 0.980665 | ≡ 1 kp/cm2 | 0.9678411 | 735.5592 | 14.22334 |

| 1 atm | 1.01325×105 | 1.01325 | 1.0332 | 1 | ≡ 760 | 14.69595 |

| 1 Torr | 133.3224 | 1.333224×10−3 | 1.359551×10−3 | 1.315789×10−3 | ≡ 1/760 atm

≈ 1 mmHg |

1.933678×10−2 |

| 1 psi | 6.8948×103 | 6.8948×10−2 | 7.03069×10−2 | 6.8046×10−2 | 51.71493 | ≡ 1 lbF /in2 |

The SI unit for pressure is the pascal (Pa), equal to one newton per square metre (N·m−2 or kg·m−1·s−2). This special name for the unit was added in 1971; before that, pressure in SI was expressed in units such as N·m−2. When indicated, the zero reference is stated in parenthesis following the unit, for example 101 kPa (abs). The pound per square inch (psi) is still in widespread use in the US and Canada, for measuring, for instance, tire pressure. A letter is often appended to the psi unit to indicate the measurement's zero reference; psia for absolute, psig for gauge, psid for differential, although this practice is discouraged by the NIST.[1]

Because pressure was once commonly measured by its ability to displace a column of liquid in a manometer, pressures are often expressed as a depth of a particular fluid (e.g., inches of water). Manometric measurement is the subject of pressure head calculations. The most common choices for a manometer's fluid are mercury (Hg) and water; water is nontoxic and readily available, while mercury's density allows for a shorter column (and so a smaller manometer) to measure a given pressure. The abbreviation "W.C." or the words "water column" are often printed on gauges and measurements that use water for the manometer.

Fluid density and local gravity can vary from one reading to another depending on local factors, so the height of a fluid column does not define pressure precisely. So measurements in "millimetres of mercury" or "inches of mercury" can be converted to SI units as long as attention is paid to the local factors of fluid density and gravity. Temperature fluctuations change the value of fluid density, while location can affect gravity.

Although no longer preferred, these manometric units are still encountered in many fields. Blood pressure is measured in millimetres of mercury (see torr) in most of the world, and lung pressures in centimeters of water are still common, as in settings for CPAP machines. Natural gas pipeline pressures are measured in inches of water, expressed as "inches W.C." Scuba divers often use a manometric rule of thumb: the pressure exerted by ten meters depth of sea water ("10 msw") is approximately equal to one atmosphere. In vacuum systems, the units torr, micrometre of mercury (micron), and inch of mercury (inHg) are most commonly used. Torr and micron usually indicates an absolute pressure, while inHg usually indicates a gauge pressure.

Atmospheric pressures are usually stated using kilopascal (kPa), or atmospheres (atm), except in American meteorology where the hectopascal (hPa) and millibar (mbar) are preferred. In American and Canadian engineering, stress is often measured in kip. Note that stress is not a true pressure since it is not scalar. In the cgs system the unit of pressure was the barye (ba), equal to 1 dyn·cm−2. In the mts system, the unit of pressure was the pieze, equal to 1 sthene per square metre.

Many other hybrid units are used such as mmHg/cm2 or grams-force/cm2 (sometimes as [[kg/cm<sup>2</sup>]] without properly identifying the force units). Using the names kilogram, gram, kilogram-force, or gram-force (or their symbols) as a unit of force is prohibited in SI; the unit of force in SI is the newton (N).

Static and dynamic pressure

Static pressure is uniform in all directions, so pressure measurements are independent of direction in an immovable (static) fluid. Flow, however, applies additional pressure on surfaces perpendicular to the flow direction, while having little impact on surfaces parallel to the flow direction. This directional component of pressure in a moving (dynamic) fluid is called dynamic pressure. An instrument facing the flow direction measures the sum of the static and dynamic pressures; this measurement is called the total pressure or stagnation pressure. Since dynamic pressure is referenced to static pressure, it is neither gauge nor absolute; it is a differential pressure.

While static gauge pressure is of primary importance to determining net loads on pipe walls, dynamic pressure is used to measure flow rates and airspeed. Dynamic pressure can be measured by taking the differential pressure between instruments parallel and perpendicular to the flow. Pitot-static tubes, for example perform this measurement on airplanes to determine airspeed. The presence of the measuring instrument inevitably acts to divert flow and create turbulence, so its shape is critical to accuracy and the calibration curves are often non-linear.

Applications

Instruments

Many instruments have been invented to measure pressure, with different advantages and disadvantages. Pressure range, sensitivity, dynamic response and cost all vary by several orders of magnitude from one instrument design to the next. The oldest type is the liquid column (a vertical tube filled with mercury) manometer invented by Evangelista Torricelli in 1643. The U-Tube was invented by Christiaan Huygens in 1661.

Hydrostatic

Hydrostatic gauges (such as the mercury column manometer) compare pressure to the hydrostatic force per unit area at the base of a column of fluid. Hydrostatic gauge measurements are independent of the type of gas being measured, and can be designed to have a very linear calibration. They have poor dynamic response.

Piston

Piston-type gauges counterbalance the pressure of a fluid with a spring (for example tire-pressure gauges of comparatively low accuracy) or a solid weight, in which case it is known as a deadweight tester and may be used for calibration of other gauges.

Liquid column

By using the pressure head equation, liquids can be used for instrumentation where gravity is present. Liquid column gauges consist of a vertical column of liquid in a tube that has ends which are exposed to different pressures. The column will rise or fall until its weight (a force applied due to gravity) is in equilibrium with the pressure differential between the two ends of the tube (a force applied due to fluid pressure). A very simple version is a U-shaped tube half-full of liquid, one side of which is connected to the region of interest while the reference pressure (which might be the atmospheric pressure or a vacuum) is applied to the other. The difference in liquid level represents the applied pressure. The pressure exerted by a column of fluid of height h and density ρ is given by the hydrostatic pressure equation, P = hgρ. Therefore, the pressure difference between the applied pressure Pa and the reference pressure P0 in a U-tube manometer can be found by solving Pa − P0 = hgρ. In other words, the pressure on either end of the liquid (shown in blue in the figure to the right) must be balanced (since the liquid is static) and so Pa = P0 + hgρ.

In most liquid column measurements, the result of the measurement is the height, h, expressed typically in mm, cm, or inches. The h is also known as the pressure head. When expressed as a pressure head, pressure is specified in units of length and the measurement fluid must be specified. When accuracy is critical, the temperature of the measurement fluid must likewise be specified, because liquid density is a function of temperature. So, for example, pressure head might be written "742.2 mmHg" or "4.2 inH2O at 59 °F" for measurements taken with mercury or water as the manometric fluid, respectively. The word "gauge" or "vacuum" may be added to such a measurement to distinguish between a pressure above or below the atmospheric pressure. Both mm of mercury and inches of water are common pressure heads which can be converted to S.I. units of pressure using unit conversion and the above formulas.

If the fluid being measured is significantly dense, hydrostatic corrections may have to be made for the height between the moving surface of the manometer working fluid and the location where the pressure measurement is desired except when measuring differential pressure of a fluid (for example across an orifice plate or venturi), in which case the density ρ should be corrected by subtracting the density of the fluid being measured.[2]

Although any fluid can be used, mercury is preferred for its high density (13.534 g/cm3) and low vapour pressure. For low pressure differences, light oil or water are commonly used (the latter giving rise to units of measurement such as inches water gauge and millimetres H2O. Liquid-column pressure gauges have a highly linear calibration. They have poor dynamic response because the fluid in the column may react slowly to a pressure change.

When measuring vacuum, the working liquid may evaporate and contaminate the vacuum if its vapor pressure is too high. When measuring liquid pressure, a loop filled with gas or a light fluid can isolate the liquids to prevent them from mixing but this can be unnecessary, for example when mercury is used as the manometer fluid to measure differential pressure of a fluid such as water. Simple hydrostatic gauges can measure pressures ranging from a few Torr (a few 100 Pa) to a few atmospheres. (Approximately 1,000,000 Pa)

A single-limb liquid-column manometer has a larger reservoir instead of one side of the U-tube and has a scale beside the narrower column. The column may be inclined to further amplify the liquid movement. Based on the use and structure following type of manometers are used[3]

- Simple Manometer

- Micromanometer

- Differential manometer

- Inverted differential manometer

McLeod gauge

A McLeod gauge isolates a sample of gas and compresses it in a modified mercury manometer until the pressure is a few millimetres of mercury. The technique is slow and unsuited to continual monitoring, but is capable of good accuracy. Unlike other manometer gauges, the McLeod gauge reading is dependent on the composition of the gas since the interpretation relies on the sample compressing as an ideal gas. Due to the compression process, the McLeod gauge completely ignores partial pressures from non-ideal vapors that condense, such as pump oils, mercury, and even water if compressed enough.

- Useful range: from around 10−4 torr [4] (roughly 10−2 Pa) to vacuums as high as 10−6 Torr (0.1 mPa),

0.1 mPa is the lowest direct measurement of pressure that is possible with current technology. Other vacuum gauges can measure lower pressures, but only indirectly by measurement of other pressure-controlled properties. These indirect measurements must be calibrated to SI units via a direct measurement, most commonly a McLeod gauge.[5]

Aneroid

Aneroid gauges are based on a metallic pressure-sensing element that flexes elastically under the effect of a pressure difference across the element. "Aneroid" means "without fluid," and the term originally distinguished these gauges from the hydrostatic gauges described above. However, aneroid gauges can be used to measure the pressure of a liquid as well as a gas, and they are not the only type of gauge that can operate without fluid. For this reason, they are often called mechanical gauges in modern language. Aneroid gauges are not dependent on the type of gas being measured, unlike thermal and ionization gauges, and are less likely to contaminate the system than hydrostatic gauges. The pressure sensing element may be a Bourdon tube, a diaphragm, a capsule, or a set of bellows, which will change shape in response to the pressure of the region in question. The deflection of the pressure sensing element may be read by a linkage connected to a needle, or it may be read by a secondary transducer. The most common secondary transducers in modern vacuum gauges measure a change in capacitance due to the mechanical deflection. Gauges that rely on a change in capacitance are often referred to as capacitance manometers.

Bourdon

The Bourdon pressure gauge uses the principle that a flattened tube tends to straighten or regain its circular form in cross-section when pressurized. Although this change in cross-section may be hardly noticeable, and thus involving moderate stresses within the elastic range of easily workable materials, the strain of the material of the tube is magnified by forming the tube into a C shape or even a helix, such that the entire tube tends to straighten out or uncoil, elastically, as it is pressurized. Eugene Bourdon patented his gauge in France in 1849, and it was widely adopted because of its superior sensitivity, linearity, and accuracy; Edward Ashcroft purchased Bourdon's American patent rights in 1852 and became a major manufacturer of gauges. Also in 1849, Bernard Schaeffer in Magdeburg, Germany patented a successful diaphragm (see below) pressure gauge, which, together with the Bourdon gauge, revolutionized pressure measurement in industry.[6] But in 1875 after Bourdon's patents expired, his company Schaeffer and Budenberg also manufactured Bourdon tube gauges.

In practice, a flattened thin-wall, closed-end tube is connected at the hollow end to a fixed pipe containing the fluid pressure to be measured. As the pressure increases, the closed end moves in an arc, and this motion is converted into the rotation of a (segment of a) gear by a connecting link that is usually adjustable. A small-diameter pinion gear is on the pointer shaft, so the motion is magnified further by the gear ratio. The positioning of the indicator card behind the pointer, the initial pointer shaft position, the linkage length and initial position, all provide means to calibrate the pointer to indicate the desired range of pressure for variations in the behavior of the Bourdon tube itself. Differential pressure can be measured by gauges containing two different Bourdon tubes, with connecting linkages.

Bourdon tubes measure gauge pressure, relative to ambient atmospheric pressure, as opposed to absolute pressure; vacuum is sensed as a reverse motion. Some aneroid barometers use Bourdon tubes closed at both ends (but most use diaphragms or capsules, see below). When the measured pressure is rapidly pulsing, such as when the gauge is near a reciprocating pump, an orifice restriction in the connecting pipe is frequently used to avoid unnecessary wear on the gears and provide an average reading; when the whole gauge is subject to mechanical vibration, the entire case including the pointer and indicator card can be filled with an oil or glycerin. Tapping on the face of the gauge is not recommended as it will tend to falsify actual readings initially presented by the gauge. The Bourdon tube is separate from the face of the gauge and thus has no effect on the actual reading of pressure. Typical high-quality modern gauges provide an accuracy of ±2% of span, and a special high-precision gauge can be as accurate as 0.1% of full scale.[7]

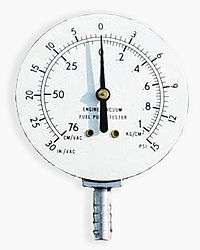

In the following illustrations the transparent cover face of the pictured combination pressure and vacuum gauge has been removed and the mechanism removed from the case. This particular gauge is a combination vacuum and pressure gauge used for automotive diagnosis:

- the left side of the face, used for measuring manifold vacuum, is calibrated in centimetres of mercury on its inner scale and inches of mercury on its outer scale.

- the right portion of the face is used to measure fuel pump pressure or turbo boost and is calibrated in fractions of 1 kgf/cm2 on its inner scale and pounds per square inch on its outer scale.

Mechanical details

Stationary parts:

- A: Receiver block. This joins the inlet pipe to the fixed end of the Bourdon tube (1) and secures the chassis plate (B). The two holes receive screws that secure the case.

- B: Chassis plate. The face card is attached to this. It contains bearing holes for the axles.

- C: Secondary chassis plate. It supports the outer ends of the axles.

- D: Posts to join and space the two chassis plates.

Moving Parts:

- Stationary end of Bourdon tube. This communicates with the inlet pipe through the receiver block.

- Moving end of Bourdon tube. This end is sealed.

- Pivot and pivot pin.

- Link joining pivot pin to lever (5) with pins to allow joint rotation.

- Lever. This is an extension of the sector gear (7).

- Sector gear axle pin.

- Sector gear.

- Indicator needle axle. This has a spur gear that engages the sector gear (7) and extends through the face to drive the indicator needle. Due to the short distance between the lever arm link boss and the pivot pin and the difference between the effective radius of the sector gear and that of the spur gear, any motion of the Bourdon tube is greatly amplified. A small motion of the tube results in a large motion of the indicator needle.

- Hair spring to preload the gear train to eliminate gear lash and hysteresis.

Diaphragm

A second type of aneroid gauge uses deflection of a flexible membrane that separates regions of different pressure. The amount of deflection is repeatable for known pressures so the pressure can be determined by using calibration. The deformation of a thin diaphragm is dependent on the difference in pressure between its two faces. The reference face can be open to atmosphere to measure gauge pressure, open to a second port to measure differential pressure, or can be sealed against a vacuum or other fixed reference pressure to measure absolute pressure. The deformation can be measured using mechanical, optical or capacitive techniques. Ceramic and metallic diaphragms are used.

For absolute measurements, welded pressure capsules with diaphragms on either side are often used.

shape:

- Flat

- corrugated

- flattened tube

- capsule

Bellows

In gauges intended to sense small pressures or pressure differences, or require that an absolute pressure be measured, the gear train and needle may be driven by an enclosed and sealed bellows chamber, called an aneroid, which means "without liquid". (Early barometers used a column of liquid such as water or the liquid metal mercury suspended by a vacuum.) This bellows configuration is used in aneroid barometers (barometers with an indicating needle and dial card), altimeters, altitude recording barographs, and the altitude telemetry instruments used in weather balloon radiosondes. These devices use the sealed chamber as a reference pressure and are driven by the external pressure. Other sensitive aircraft instruments such as air speed indicators and rate of climb indicators (variometers) have connections both to the internal part of the aneroid chamber and to an external enclosing chamber.

Magnetic coupling

These gauges use the attraction of two magnets to translate differential pressure into motion of a dial pointer. As differential pressure increases, a magnet attached to either a piston or rubber diaphragm moves. A rotary magnet that is attached to a pointer then moves in unison. To create different pressure ranges, the spring rate can be increased or decreased.

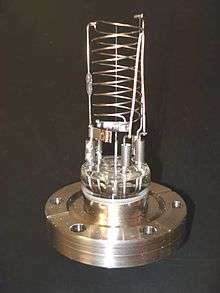

Spinning rotor gauge

The spinning rotor gauge works by measuring the amount a rotating ball is slowed by the viscosity of the gas being measured. The ball is made of steel and is magnetically levitated inside a steel tube closed at one end and exposed to the gas to be measured at the other. The ball is brought up to speed (about 2500 rad/s), and the speed measured after switching off the drive, by electromagnetic transducers.[9] The range of the instrument is 10−5 to 102 Pa (103 Pa with less accuracy). It is accurate and stable enough to be used as a secondary standard. The instrument requires some skill and knowledge to use correctly. Various corrections must be applied and the ball must be spun at a pressure well below the intended measurement pressure for five hours before using. It is most useful in calibration and research laboratories where high accuracy is required and qualified technicians are available.[10]

Electronic pressure sensors

- Piezoresistive Strain Gage

- Uses the piezoresistive effect of bonded or formed strain gauges to detect strain due to applied pressure.

- Capacitive

- Uses a diaphragm and pressure cavity to create a variable capacitor to detect strain due to applied pressure.

- Magnetic

- Measures the displacement of a diaphragm by means of changes in inductance (reluctance), LVDT, Hall Effect, or by eddy current principle.

- Piezoelectric

- Uses the piezoelectric effect in certain materials such as quartz to measure the strain upon the sensing mechanism due to pressure.

- Optical

- Uses the physical change of an optical fiber to detect strain due to applied pressure.

- Potentiometric

- Uses the motion of a wiper along a resistive mechanism to detect the strain caused by applied pressure.

- Resonant

- Uses the changes in resonant frequency in a sensing mechanism to measure stress, or changes in gas density, caused by applied pressure.

Thermal conductivity

Generally, as a real gas increases in density -which may indicate an increase in pressure- its ability to conduct heat increases. In this type of gauge, a wire filament is heated by running current through it. A thermocouple or resistance thermometer (RTD) can then be used to measure the temperature of the filament. This temperature is dependent on the rate at which the filament loses heat to the surrounding gas, and therefore on the thermal conductivity. A common variant is the Pirani gauge, which uses a single platinum filament as both the heated element and RTD. These gauges are accurate from 10−3 Torr to 10 Torr, but their calibration is sensitive to the chemical composition of the gases being measured.

Pirani (one wire)

A Pirani gauge consist of a metal wire open to the pressure being measured. The wire is heated by a current flowing through it and cooled by the gas surrounding it. If the gas pressure is reduced, the cooling effect will decrease, hence the equilibrium temperature of the wire will increase. The resistance of the wire is a function of its temperature: by measuring the voltage across the wire and the current flowing through it, the resistance (and so the gas pressure) can be determined. This type of gauge was invented by Marcello Pirani.

Two-wire

In two-wire gauges, one wire coil is used as a heater, and the other is used to measure temperature due to convection. Thermocouple gauges and thermistor gauges work in this manner using thermocouple or thermistor, respectively, to measure the temperature of the heated wire.

Ionization gauge

Ionization gauges are the most sensitive gauges for very low pressures (also referred to as hard or high vacuum). They sense pressure indirectly by measuring the electrical ions produced when the gas is bombarded with electrons. Fewer ions will be produced by lower density gases. The calibration of an ion gauge is unstable and dependent on the nature of the gases being measured, which is not always known. They can be calibrated against a McLeod gauge which is much more stable and independent of gas chemistry.

Thermionic emission generate electrons, which collide with gas atoms and generate positive ions. The ions are attracted to a suitably biased electrode known as the collector. The current in the collector is proportional to the rate of ionization, which is a function of the pressure in the system. Hence, measuring the collector current gives the gas pressure. There are several sub-types of ionization gauge.

- Useful range: 10−10 - 10−3 torr (roughly 10−8 - 10−1 Pa)

Most ion gauges come in two types: hot cathode and cold cathode. In the hot cathode version, an electrically heated filament produces an electron beam. The electrons travel through the gauge and ionize gas molecules around them. The resulting ions are collected at a negative electrode. The current depends on the number of ions, which depends on the pressure in the gauge. Hot cathode gauges are accurate from 10−3 Torr to 10−10 Torr. The principle behind cold cathode version is the same, except that electrons are produced in the discharge of a high voltage. Cold Cathode gauges are accurate from 10−2 Torr to 10−9 Torr. Ionization gauge calibration is very sensitive to construction geometry, chemical composition of gases being measured, corrosion and surface deposits. Their calibration can be invalidated by activation at atmospheric pressure or low vacuum. The composition of gases at high vacuums will usually be unpredictable, so a mass spectrometer must be used in conjunction with the ionization gauge for accurate measurement.[11]

Hot cathode

A hot-cathode ionization gauge is composed mainly of three electrodes acting together as a triode, wherein the cathode is the filament. The three electrodes are a collector or plate, a filament, and a grid. The collector current is measured in picoamps by an electrometer. The filament voltage to ground is usually at a potential of 30 volts, while the grid voltage at 180–210 volts DC, unless there is an optional electron bombardment feature, by heating the grid, which may have a high potential of approximately 565 volts. The most common ion gauge is the hot-cathode Bayard-Alpert gauge, with a small ion collector inside the grid. A glass envelope with an opening to the vacuum can surround the electrodes, but usually the Nude Gauge is inserted in the vacuum chamber directly, the pins being fed through a ceramic plate in the wall of the chamber. Hot-cathode gauges can be damaged or lose their calibration if they are exposed to atmospheric pressure or even low vacuum while hot. The measurements of a hot-cathode ionization gauge are always logarithmic.

Electrons emitted from the filament move several times in back and forth movements around the grid before finally entering the grid. During these movements, some electrons collide with a gaseous molecule to form a pair of an ion and an electron (Electron ionization). The number of these ions is proportional to the gaseous molecule density multiplied by the electron current emitted from the filament, and these ions pour into the collector to form an ion current. Since the gaseous molecule density is proportional to the pressure, the pressure is estimated by measuring the ion current.

The low-pressure sensitivity of hot-cathode gauges is limited by the photoelectric effect. Electrons hitting the grid produce x-rays that produce photoelectric noise in the ion collector. This limits the range of older hot-cathode gauges to 10−8 Torr and the Bayard-Alpert to about 10−10 Torr. Additional wires at cathode potential in the line of sight between the ion collector and the grid prevent this effect. In the extraction type the ions are not attracted by a wire, but by an open cone. As the ions cannot decide which part of the cone to hit, they pass through the hole and form an ion beam. This ion beam can be passed on to a:

- Faraday cup

- Microchannel plate detector with Faraday cup

- Quadrupole mass analyzer with Faraday cup

- Quadrupole mass analyzer with Microchannel plate detector Faraday cup

- ion lens and acceleration voltage and directed at a target to form a sputter gun. In this case a valve lets gas into the grid-cage.

Cold cathode

There are two subtypes of cold-cathode ionization gauges: the Penning gauge (invented by Frans Michel Penning), and the Inverted magnetron, also called a Redhead gauge. The major difference between the two is the position of the anode with respect to the cathode. Neither has a filament, and each may require a DC potential of about 4 kV for operation. Inverted magnetrons can measure down to 1x10−12 Torr.

Likewise, cold-cathode gauges may be reluctant to start at very low pressures, in that the near-absence of a gas makes it difficult to establish an electrode current - in particular in Penning gauges, which use an axially symmetric magnetic field to create path lengths for electrons that are of the order of metres. In ambient air, suitable ion-pairs are ubiquitously formed by cosmic radiation; in a Penning gauge, design features are used to ease the set-up of a discharge path. For example, the electrode of a Penning gauge is usually finely tapered to facilitate the field emission of electrons.

Maintenance cycles of cold cathode gauges are, in general, measured in years, depending on the gas type and pressure that they are operated in. Using a cold cathode gauge in gases with substantial organic components, such as pump oil fractions, can result in the growth of delicate carbon films and shards within the gauge that eventually either short-circuit the electrodes of the gauge or impede the generation of a discharge path.

Calibration

Pressure gauges are either direct- or indirect-reading. Hydrostatic and elastic gauges measure pressure are directly influenced by force exerted on the surface by incident particle flux, and are called direct reading gauges. Thermal and ionization gauges read pressure indirectly by measuring a gas property that changes in a predictable manner with gas density. Indirect measurements are susceptible to more errors than direct measurements.

- Dead-weight tester

- McLeod

- mass spec + ionization

Dynamic transients

When fluid flows are not in equilibrium, local pressures may be higher or lower than the average pressure in a medium. These disturbances propagate from their source as longitudinal pressure variations along the path of propagation. This is also called sound. Sound pressure is the instantaneous local pressure deviation from the average pressure caused by a sound wave. Sound pressure can be measured using a microphone in air and a hydrophone in water. The effective sound pressure is the root mean square of the instantaneous sound pressure over a given interval of time. Sound pressures are normally small and are often expressed in units of microbar.

- frequency response of pressure sensors

- resonance

Standards

The American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) has developed two separate and distinct standards on pressure Measurement, B40.100 and PTC 19.2. B40.100 provides guidelines on Pressure Indicated Dial Type and Pressure Digital Indicating Gauges, Diaphragm Seals, Snubbers, and Pressure Limiter Valves. PTC 19.2 provides instructions and guidance for the accurate determination of pressure values in support of the ASME Performance Test Codes. The choice of method, instruments, required calculations, and corrections to be applied depends on the purpose of the measurement, the allowable uncertainty, and the characteristics of the equipment being tested. The methods for pressure measurement and the protocols used for data transmission are also provides. Guidance is given for setting up the instrumentation and determining the uncertainty of the measurement. Information regarding the instrument type, design, applicable pressure range, accuracy, output, and relative cost is provided. Information is also provided on pressure-measuring devices that are used in field environments i.e., Piston Gauges, Manometers, and Low-Absolute-Pressure (Vacuum) Instruments. These methods are designed to assist in the evaluation of measurement uncertainty based on current technology and engineering knowledge, taking into account published instrumentation specifications and measurement and application techniques. This Supplement provides guidance in the use of methods to establish the pressure-measurement uncertainty.

History

European (CEN) Standard

- EN 472 : Pressure gauge - Vocabulary.

- EN 837-1 : Pressure gauges. Bourdon tube pressure gauges. Dimensions, metrology, requirements and testing.

- EN 837-2 : Pressure gauges. Selection and installation recommendations for pressure gauges.

- EN 837-3 : Pressure gauges. Diaphragm and capsule pressure gauges. Dimensions, metrology, requirements, and testing.

US ASME Standards

- B40.100-2013: Pressure gauges and Gauge attachments.

- PTC 19.2-2010 : Performance test code for pressure measurement.

See also

References

- ↑ NIST

- ↑ Methods for the Measurement of Fluid Flow in Pipes, Part 1. Orifice Plates, Nozzles and Venturi Tubes. British Standards Institute. 1964. p. 36.

- ↑ [Was: "fluidengineering.co.nr/Manometer.htm". At 1/2010 that took me to bad link. Types of fluid Manometers]

- ↑ Techniques of high vacuum

- ↑ Beckwith, Thomas G.; Roy D. Marangoni & John H. Lienhard V (1993). "Measurement of Low Pressures". Mechanical Measurements (Fifth ed.). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. pp. 591–595. ISBN 0-201-56947-7.

- ↑ The Engine Indicator Canadian Museum of Making

- ↑ Boyes, Walt (2008). Instrumentation Reference Book (Fourth ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 1312.

- ↑ Product brochure from Schoonover, Inc

- ↑ A. Chambers, Basic Vacuum Technology, pp. 100-102, CRC Press, 1998 ISBN 0585254915.

- ↑ John F. O'Hanlon, A User's Guide to Vacuum Technology, pp. 92-94, John Wiley & Sons, 2005 ISBN 0471467154.

- ↑ Robert M. Besançon, ed. (1990). "Vacuum Techniques". The Encyclopedia of Physics (3rd ed.). Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York. pp. 1278–1284. ISBN 0-442-00522-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pressure gauge. |