Urinary bladder

| Urinary bladder | |

|---|---|

|

1. Human urinary system: 2. Kidney, 3. Renal pelvis, 4. Ureter, 5. Urinary bladder, 6. Urethra. (Left side with frontal section) 7. Adrenal gland Vessels: 8. Renal artery and vein, 9. Inferior vena cava, 10. Abdominal aorta, 11. Common iliac artery and vein With transparency: 12. Liver, 13. Large intestine, 14. Pelvis | |

|

Female bladder (visible due to lack of prostate), showing transitional epithelium as well as part of the wall in a histological cut-out. | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | urogenital sinus |

| System | Urinary system |

| Artery |

Superior vesical artery Inferior vesical artery Umbilical artery Vaginal artery |

| Vein | Vesical venous plexus |

| Nerve | Vesical nervous plexus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | vesica urinaria |

| MeSH | A05.810.161 |

| Dorlands /Elsevier | Urinary bladder |

| TA | A08.3.01.001 |

| FMA | 15900 |

The urinary bladder is the organ that collects urine excreted by the kidneys before disposal by urination. A hollow[1] muscular, and distensible (or elastic) organ, the bladder sits on the pelvic floor. Urine enters the bladder via the ureters and exits via the urethra. There is no exact measurement for the volume of the human bladder, but different sources mention 500 mL (~17 oz) to 1000 mL (~34 oz).[2]

Structure

Detrusor muscle

The detrusor muscle is a layer of the urinary bladder wall made of smooth muscle fibers arranged in spiral, longitudinal, and circular bundles. When the bladder is stretched, this signals the parasympathetic nervous system to contract the detrusor muscle. This encourages the bladder to expel urine through the urethra. A meta-analysis on the effect of voiding position on urodynamics in males found that sitting down allows for improved contraction of the detrusor muscle.[3]

Fundus

The fundus of the bladder is the base of the bladder, formed by the posterior wall. It is lymphatically drained by the external iliac lymph nodes. The peritoneum lies superior to the fundus.

Innervation

The bladder receives motor innervation from both sympathetic fibers, most of which arise from the hypogastric plexuses and nerves, and parasympathetic fibers, which come from the pelvic splanchnic nerves and the inferior hypogastric plexus.[4]

Sensation from the bladder is transmitted to the central nervous system (CNS) via general visceral afferent fibers (GVA). GVA fibers on the superior surface follow the course of the sympathetic efferent nerves back to the CNS, while GVA fibers on the inferior portion of the bladder follow the course of the parasympathetic efferents.[4]

For the urine to exit the bladder, both the autonomically controlled internal sphincter and the voluntarily controlled external sphincter must be opened. Problems with these muscles can lead to incontinence.[5]

Histology

The urinary bladder is lined with transitional epithelium. It does not produce mucus.[6] The internal lining of the bladder wall is termed the urothelium and lamina propria, and this layer is thought to regulate some aspects of the overall bladder physiology in response to stimuli such as stretch during filling.[7]

-

Vertical section of bladder wall.

-

Layers of the urinary bladder wall and cross section of the detrusor muscle.

Development

The human urinary bladder is derived in embryo from the urogenital sinus and, it is initially continuous with the allantois. In males, the base of the bladder lies between the rectum and the pubic symphysis. It is superior to the prostate, and separated from the rectum by the rectovesical excavation. In females, the bladder sits inferior to the uterus and anterior to the vagina; thus, its maximum capacity is lower than in males. It is separated from the uterus by the vesicouterine excavation. In infants and young children, the urinary bladder is in the abdomen even when empty.[8]

Function

Urine, excreted by the kidneys, collects in the bladder before disposal by urination. The urinary bladder usually holds 300-350 ml of urine. As urine accumulates, the rugae flatten and the wall of the bladder thins as it stretches, allowing the bladder to store larger amounts of urine without a significant rise in internal pressure.[9]

Clinical significance

Frequent urination can be due to excessive urine production, small bladder capacity, irritability or incomplete emptying. Males with an enlarged prostate urinate more frequently. One definition of overactive bladder is when a person urinates more than eight times per day,[10] though there can be other causes of urination frequency. Though both urinary frequency and volumes have been shown to have a circadian rhythm, meaning day and night cycles,[11] it is not entirely clear how these are disturbed in the overactive bladder.

Disorders of or related to the bladder include:

- Bladder cancer

- Bladder exstrophy

- Bladder infection

- Bladder spasm

- Bladder sphincter dyssynergia, a condition in which the sufferer cannot coordinate relaxation of the urethra sphincter with the contraction of the bladder muscles

- Bladder stones

- Cystitis

- Hematuria, or presence of blood in the urine, is a reason to seek medical attention without delay, as it is a symptom of bladder cancer as well as bladder and kidney stones

- Interstitial Cystitis

- Overactive bladder, a condition that affects a large number of people

- Paruresis

- Urinary incontinence

- Urinary retention

Other animals

Bladders occur throughout much of the animal kingdom, but are very diverse in form and in some cases are not homologous with the urinary bladder in humans. The pig bladder is very similar to the human bladder.

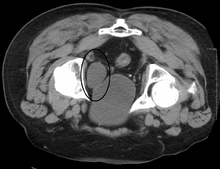

Additional images

-

Median sagittal section of female pelvis.

-

The peritoneum of the male pelvis.

-

Median sagitta section of male pelvis.

-

Vertical section of bladder, penis, and urethra.

-

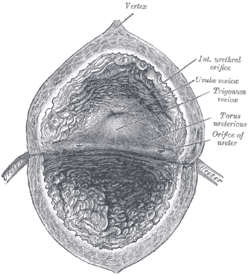

The interior of bladder.

-

Fundus of the bladder with the vesiculæ seminales.

-

Female pelvis and its contents, seen from above and in front.

-

The bladder can be seen highlighted in yellow in the illustration.

See also

- Artificial urinary bladder

- Bladder augmentation

- Neurogenic bladder

- Ureterocele

- Urodynamics

- Uvula of urinary bladder

- Vesicouretic reflux

References

- ↑ Howard A. Werman, Keith J. Karren.

- ↑ Volume of a Human Bladder

- ↑ de Jong, Y; Pinckaers, JH; Ten Brinck, RM; Lycklama À Nijeholt, AA; Dekkers, OM (2014). "Urinating Standing versus Sitting: Position Is of Influence in Men with Prostate Enlargement. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.". PLOS ONE 9 (7): e101320. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0101320. PMC 4106761. PMID 25051345.

- 1 2 Moore, Keith; Anne Agur (2007). Essential Clinical Anatomy, Third Edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 227–228. ISBN 0-7817-6274-X.

- ↑ "Urinary Incontinence - Causes". NHS. Retrieved 2013-08-21.

- ↑ Chin T, Liu , Tsai H, Wei C (September 2007). "Vaginal reconstruction using urinary bladder flap in a patient with cloacal malformation". Journal of Pediatric Surgery 42 (9): 1612–5. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.04.040. PMID 17848259.

- ↑ Moro C, Uchiyama J, Chess-Williams R (December 2011). "Urothelial/lamina propria spontaneous activity and the role of M3 muscarinic receptors in mediating rate responses to stretch and carbachol". Urology. 76 (6): 1442.e9–15. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2011.08.039. PMID 22001099.

- ↑ Moore, Keith L.; Dalley, Arthur F (2006). Clinically Oriented Anatomy (5th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- ↑ Marieb, Mallatt. "23". Human Anatomy (5th ed.). Pearson International. p. 700.

- ↑ "Overactive Bladder". Cornell Medical College. Retrieved 2013-08-21.

- ↑ Negoro, Hiromitsu (2012). "Involvement of urinary bladder Connexin43 and the circadian clock in coordination of diurnal micturition rhythm". doi:10.1038/ncomms1812.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Urinary bladder. |

- Histology at KUMC epithel-epith09 "Urinary Bladder"

- Anatomy photo: Urinary/mammal/bladder/bladder1 - Comparative Organology at University of California, Davis — "Mammal, bladder (LM, Medium)"

- Virtual Slidebox at Univ. Iowa Slide 445

- Anatomy photo:43:07-0100 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center — "The Female Pelvis: The Urinary bladder"

- Anatomy photo:44:04-0103 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center — "The Male Pelvis: The Urinary bladder"

- Bladder (ISSN 2327-2120) — An open-access journal on bladder biology and diseases.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|