Uralic–Yukaghir languages

| Uralic–Yukaghir | |

|---|---|

| (controversial) | |

| Geographic distribution: | Scandinavia, Siberia, Eastern Europe |

| Linguistic classification: | Indo-Uralic ? |

| Subdivisions: | |

| Glottolog: | None |

|

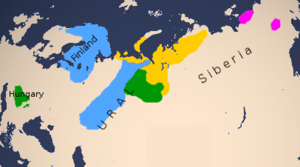

The Uralic and Yukaghir languages. After Merritt Ruhlen, A Guide to the World's Languages (1987), p. 64. Color key: light blue: Finno-Permic languages. darkgreen: Ugric languages. yellow: Samoyedic languages. magenta: Yukaghir languages. | |

Uralic–Yukaghir is a proposed language family composed of Uralic and Yukaghir. It is also known as Uralo-Yukaghir.

Uralic is a large and diverse family of languages spoken in northern and eastern Europe and northwestern Siberia. Among the better-known Uralic languages are Finnish, Estonian, and Hungarian.

Yukaghir is a small family of languages spoken in eastern Siberia. It formerly extended over a much wider area (Collinder 1965:30). It consists of two languages, Tundra Yukaghir and Kolyma Yukaghir.

History

The idea that the Uralic and Yukaghir languages are related is not new. It was advanced in passing by Holger Pedersen in his 1931 book Linguistic Science in the Nineteenth Century (p. 338). Pedersen included both languages in his proposed Nostratic language family (ib.).

A genetic relationship between Uralic and Yukaghir was argued for in Jukagirisch und Uralisch ('Yukaghir and Uralic'), a 1940 work by Björn Collinder, one of the leading Uralic specialists of the 20th century (Greenberg 2005:124). Collinder was inspired by a 1907 article by Heikki Paasonen, which pointed to similarities between Uralic and Yukaghir, though it did not identify the two languages as genetically related (Greenberg, ib.).

Uralic–Yukaghir is listed as a language family in A Guide to the World's Languages by Merritt Ruhlen (1987).

Uralic and Yukaghir are listed as a language family, forming a subgroup of a higher-order family called "Eurasiatic", in Joseph Greenberg's Indo-European and Its Closest Relatives (2000–2002). However, Greenberg did not present a discursive argument for this subgroup, presumably leaving it to the reader to work it out from the data on grammar and vocabulary he presented.

The Uralic–Yukaghir family has been accepted by the American Nostraticist Allan Bomhard (2008:176, citing Ruhlen 1987:64–65) but without presenting any argument for it, and Russian linguist Vladimir Napolskikh.

Arguments

Collinder summarizes his case for, not merely a relationship between Uralic and Yukaghir, but for a Uralic–Yukaghir language family, in his Introduction to the Uralic Languages (1965:30):

- The features common to Yukagir and Uralic are so numerous and so characteristic that they must be remainders of a primordial unity. The case system of Yukagir is almost identical with that of Northern Samoyed. The imperative of the verbs is formed with the same suffixes as in Southern Samoyed and the most conservative of the Fenno-Ugric languages. The two negative auxiliary verbs of the Uralic languages are also found in Yukagir. There are striking common traits in verb derivation. Most of the pronominal stems are more or less identical. Yukagir has half a hundred words in common with Uralic, in addition to those that may fairly be suspected of being loanwords. This number is not lower than should be expected on the assumption that Yukagir is akin to Uralic. In Yukagir texts one may find sentences of up to a dozen words that consist exclusively or almost exclusively of words that also occur in Uralic. Nothing in the phonologic or morphologic structure of Yukagir contradicts the hypothesis of affinity, and Yukagir agrees well with Uralic as far as the syntax is concerned.

Collinder goes on to compare Uralic with Indo-European (1965:30–34). He begins by saying, "An Indo-Uralic affinity is far from being strictly proved", and emphasizes that he has not been able to find as many "plausible" cognates for Uralic and Indo-European as for Uralic and Yukaghir, at most about twenty. He then goes on to list 15 of these cognates, with reflexes in Uralic and Indo-European languages, and to discuss similarities between Uralic and Indo-European in morphology. He makes no explicit statement on the subgrouping of the language family that must have existed if Uralic, Yukaghir, and Indo-European are all related. While the similarities he attributes to Uralic and Yukaghir, but not to Indo-European, such as the imperative endings, show closer kinship of Uralic and Yukaghir than of Uralic and Indo-European, the similarities he attributes to Uralic and Indo-European, but not to Uralic and Yukaghir, could also be placed in the balance, for example a plural in *-i.

Collinder appears to enumerate approximately as many morphological similarities between Uralic and Indo-European as between Uralic and Yukaghir and at least as many similarities in pronouns (though his treatment of the pronouns is not very comprehensive), so that at bottom the case he makes, if any, for a closer relationship between Uralic and Yukaghir than between Uralic and Indo-European comes down to the fact that Uralic and Yukaghir, in his view, have about two and a half times as many fairly secure lexical cognates as Uralic and Indo-European — a fact that is certainly suggestive but cannot, in the present state of the question, be considered definitive.

Greenberg (2002) lists 115 lexical cognates for Uralic and Indo-European versus 44 lexical cognates for Uralic and Yukaghir. He lists 35 lexical cognates for Indo-European and Yukaghir. Of these cognates, 27 are common to Indo-European, Uralic, and Yukaghir.

Even if one considers Greenberg's listings to be only the result of inspection, as they do not involve the construction of a comprehensive set of sound correspondences, they at least constitute a suggestive preliminary result. (One should note however that a large number of Proto-Uralic lexemes are traditionally explained as loanwords from Proto-Indo-European.)

The figures could also be skewed by the fact that the Indo-European and Uralic languages are much more heavily attested than the Yukaghir ones. However, the impressive figure is the 44 Uralic / Yukaghir cognates versus the 35 Indo-European / Yukaghir ones. This figure does not by any means suggest an overwhelmingly closer relationship of Yukaghir and Uralic than of Yukaghir and Indo-European, especially since the opportunities for mutual influence were much greater between Yukaghir and Uralic than between Yukaghir and Indo-European, both with regard to the transmission of innovations and the conservation of older forms (on the latter, cf. Sweet 1900:120–121).

It therefore appears that an explicit case for a Uralic–Yukaghir language family, as opposed to a Uralic–Yukaghir kinship at some unspecified higher level, has not been made. Collinder (1965:30) has vaguely implied the existence of a Uralic–Yukaghir genetic node, and in this he seems to have been followed by Ruhlen and Greenberg, followed in turn by Bomhard. The actual relations of these languages remain to be scrutinized in detail. No work of synthesis of a definitive nature has appeared on this subject. As in several other cases of this sort (see Ural–Altaic languages), that Uralic and Yukaghir are related has been argued for in some detail, but how they are related remains uncertain.

It is therefore not surprising that, at the present time (2009), the validity of the Uralic–Yukaghir family is controversial. The questions that need to be answered to make a definitive determination in favor of it or against it are:

- Can a genetic relationship between Uralic and Yukaghir be shown?

- If such a relationship can be shown, is it a close one (Uralic and Yukaghir form a language family), or a more distant one (Uralic and Yukaghir are related, but as independent members of a larger language family, such as the proposed Uralo-Siberian grouping)? (Cf. Greenberg 2005:325.)

In answering these questions, a key additional question is:

- To what extent are any non-coincidental similarities due to descent from a common ancestor, to what extent are they due to borrowing caused by language contact?

The last question is a source of controversy, since historical linguists are divided into two opposed camps that have been called "Geneticists" and "Diffusionists" by Merritt Ruhlen (1994:113–114) and are sometimes caricatured as "lumpers and splitters". This conflict will not soon be resolved. However, the fact that, for instance, no-one still believes in the Hamitic family or that the Dené–Yeniseian family has recently attained general acceptance suggests that linguistic science may yet be able to resolve some of these seemingly intractable issues (cf. Vajda 2008).

Häkkinen (2012) rejects a genetic link between Uralic and Yukaghir, arguing that the grammatical systems show too few convincing resemblances, especially the morphology, and proposes instead that many apparent Uralic–Yukaghir cognates are really borrowed from an early stage of Uralic (ca. 3000 BC; he dates Proto-Uralic at ca. 2000 BC) into an early stage of Yukaghir, while Uralic was (according to him) spoken near the Sayan region and Yukaghir near the Upper Lena River and near Lake Baikal. Aikio (2014) agrees that Uralic–Yukaghir is unsupported and implausible and that several apparent cognates are borrowings from Uralic into Yukaghir, though he rejects some of the examples adduced by Häkkinen as spurious or accidental resemblances and puts the date of borrowing much later, arguing that the loanwords he accepts as valid were borrowed from an early stage of Samoyedic (preceding Proto-Samoyedic; thus roughly in the 1st millennium BC) into Yukaghir, in the same general region west of Lake Baikal.

The evidence of the Uralic–Yukaghir negative verb

A more decisive piece of evidence that Uralic and Yukaghir form a valid genetic node comes from the presence of similar negative verb formations in each. In 1933, the pioneering Indo-Europeanist Holger Pedersen published a comparative study of the verb endings in Uralic and Indo-European. According to Pedersen (1933: §8), the Uralic negative verb was formed from a verb *e- meaning 'be' plus the personal endings, which are identical to the personal pronouns. For instance, for the verb *mene 'go', the Proto-Uralic forms would have been: 1s. *e-m mene, 2s. *e-t mene; 1p. *e-me mene, 2p. *e-te mene meaning 'I do not go', 'thou dost not go', etc., literally 'be-me go', 'be-thou go', etc. The Uralic negative particle *ne 'not' would have originally formed part of the expression, as *ne e-m mene 'not be-me go' etc. What made it possible to drop the negative particle was that there was no morphological or syntactic possibility of confusing the expression with the positive verb, which had the form 1s. *mene-m, 2s. *mene-t; 1p. *mene-me, 2p. *mene-te (still preserved without change in Finnish, except for final *-m > -n) 'I go', etc. The dropping of the negative particle is well-attested by such expressions as French pas, personne, rien and Old Norse engi, eigi (ib.).

Pedersen’s argument implies that the Uralic negative verb is very ancient, for three reasons: (1) The Uralic negative verb represents a worn-down formation and is therefore presumably an old one. (2) It is built on an obsolete verb ‘to be’. (3) Most decisively, it is found in all branches of Uralic, including Samoyedic. Therefore, it is at least as ancient as Proto-Uralic, that is to say, some 4,500 or 6,500 years old, according to the two prevailing current estimates.

The Yukaghir negative verb is unlikely to be borrowed from Uralic, because morphological formations are rarely borrowed. Yet no evidence for the Uralic/Yukaghir negative verb formation is found in the Indo-European languages. It thus seems likely that the Uralic/Yukaghir negative verb goes back to a period of primitive Uralic–Yukaghir unity, from which Indo-European was separate. It could nevertheless be imagined that Indo-European once had this negative verb, but had lost it by Proto-Indo-European times, so this evidence is not conclusive, though strongly suggestive.

The principal pronouns in Yukaghir, Uralic, and Indo-European

| Meaning | Yukaghir | Uralic | Indo-European |

|---|---|---|---|

| 'I, me' (first person singular) | met | *mun, *mina 1 | *egom (nominative) *mene (genitive) 2 |

| 'you' (second person singular) | tet | *tun, *tina 1 | *tu (nominative) 3 *tewe (genitive) |

| 'this', 'that' (demonstrative pronoun) | tiŋ (Tundra), tuŋ (Kolyma) 'this' taŋ 'that' | *tä 'this' 4 *to 'that' 5 | *to- 'this, that' |

| 'who?, what?' (interrogative pronoun) | kin 'who?' (Kolyma) | *ki ~ *ke ~ *ku ~ *ko 'who?, what?' *ken 'who?' 6 | *kʷi- ~ *kʷe- ~ *kʷo- 'who?, what?' *kʷi/e/o- + *-ne 'who?, what?' 7 |

Chief sources for table: Greenberg 2000, Szemerényi 1996. When Yukaghir alone is cited, it indicates the Tundra and Kolyma dialects have the same form. An asterisk indicates reconstructed forms.

Notes to table

- Two different sets are reconstructed. The first is seen in e.g. Udmurt mon, ton, the second in e.g. Estonian mina, sina.

- E.g. English mine.

- E.g. English thou.

- E.g. Finnish tä-mä.

- E.g. Estonian too.

- E.g. Finnish ken.

- E.g. Latin quidne.

Bibliography

Works cited

- Aikio, Ante. 2014. "The Uralic–Yukaghir lexical correspondences: genetic inheritance, language contact or chance resemblance?" Finnisch-ugrische Forschungen 62. Online article

- Bomhard, Allan R. 2008. Reconstructing Proto-Nostratic: Comparative Phonology, Morphology, and Vocabulary, 2 volumes. Leiden: Brill.

- Collinder, Björn. 1940. Jukagirisch und Uralisch. Uppsala Universitets Årsskrift 8. Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Collinder, Björn. 1965. An Introduction to the Uralic Languages. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Greenberg, Joseph H. 2000. Indo-European and Its Closest Relatives: The Eurasiatic Language Family, Volume 1: Grammar. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

- Greenberg, Joseph H. 2002. Indo-European and Its Closest Relatives: The Eurasiatic Language Family, Volume 2: Lexicon. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

- Greenberg, Joseph H. 2005. Genetic Linguistics: Essays on Theory and Method, edited by William Croft. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Häkkinen, Jaakko. 2012. "Early contacts between Uralic and Yukaghir". Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran Toimituksia − Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne 264, pp. 91–101. Helsinki: Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura. Online article (pdf)

- Paasonen, Heikki. 1907. "Zur Frage von der Urverwandschaft der finnisch-ugrischen und indoeuropäischen Sprachen" ('On the question of the original relationship of the Finnish-Ugric and Indo-European languages'). Finnisch-ugrische Forschungen 17:13–31.

- Pedersen, Holger. 1931. Linguistic Science in the Nineteenth Century: Methods and Results, translated from the Danish by John Webster Spargo. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Pedersen, Holger. 1933. "Zur Frage nach der Urverwandtschaft des Indoeuropäischen mit dem Ugrofinnischen." Mémoires de la Société finno-ougrienne 67:308–325.

- Ruhlen, Merritt. 1987. A Guide to the World's Languages, Volume 1: Classification (only volume to appear to date). Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

- Ruhlen, Merritt. 1994. On the Origin of Languages: Studies in Linguistic Taxonomy. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

- Sweet, Henry. 1900. The History of Language. London: J.M. Dent & Co. (Reprints: 1901, 1995, 2007.)

- Szemerényi, Oswald. 1996. Introduction to Indo-European Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Vajda, Edward. 2008. "Dene–Yeniseic in past and future perspective." Online article (pdf)

Further reading

- Angere, J. 1956. Die uralo-jukagirische Frage. Ein Beitrag zum Problem der sprachlichen Urverwandschaft. Stockholm: Almqvist & Viksell.

- Bouda, Karl. 1940. "Die finnisch-ugrisch-samojedische Schicht des Jukagirischen." Ungarische Jahrbücher 20, 80–101.

- Collinder, Björn. 1957. "Uralo-jukagirische Nachlese." Uppsala Universitets Årsskrift 12, 105–130.

- Collinder, Björn. 1965. "Hat das Uralische Verwandte? Eine sprachvergleichende Untersuchung." Uppsala Universitets Årsskrift 1, 109–180.

- Fortescue, Michael. 1998. Language Relations Across Bering Strait: Reappraising the Archaeological and Linguistic Evidence. London and New York: Cassell.

- Hyllested, Adam. 2010. "Internal Reconstruction vs. External Comparison: The Case of the Indo-Uralic Laryngeals." Internal Reconstruction in Indo-European, eds. J.E. Rasmussen & T. Olander, 111–136. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press.

- Janhunen, Juha. 2009. "Proto-Uralic—what, where, and when?" Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran Toimituksia 258. pp. 57–78. Online article.

- Mithen, Steven. 2003. After the Ice: A Global Human History 20,000 – 5000 BC. Orion Publishing Co.

- Nikolaeva, Irina. 1986. "Yukaghir-Altaic parallels" (in Russian). Istoriko-kul'turnye kontakty narodov altajskoj jazykovoj obshchnosti: Tezisy dolkadov XXIX sessii Postojannoj Mezhdunarodnoj Altaisticheskoj Konferencii PIAC, Vol. 2: Lingvistika, pp. 84–86. Tashkent: Akademija Nauk.

- Nikolaeva, Irina. 1987. "On the reconstruction of Proto-Yukaghir: Inlaut consonantism" (in Russian). Jazyk-mif-kul'tura narodov Sibir, 43–48. Jakutsk: JaGU.

- Nikolaeva, Irina. 1988. "On the correspondence of Uralic sibilants and affricates in Yukaghir" (in Russian). Sovetskoe Finnougrovedenie 2, 81–89.

- Nikolaeva, Irina. 1988. The Problem of Uralo-Yukaghir Genetic Relationship (in Russian). PhD dissertation. Moscow: Institute of Linguistics.

- Rédei, K. 1990. "Zu den uralisch-jukagirischen Sprachkontakten." Congressus septimus internationalis Fenno-Ugristarum. Pars 1 A. Sessiones plenares, 27–36. Debrecen.

- Rédei, K. 1999. "Zu den uralisch-jukagirischen Sprachkontakten." Finnisch-ugrische Forschungen 55, 1–58. Online article (limited access)

- Sauvegeot, Au. 1963. "L'appartenance du youkaguir." Ural-altaische Jahrbücher 35, 109–117.

- Sauvegeot, Au. 1969. "La position du youkaguir." Ural-altaische Jahrbücher 41, 344–359.

- Swadesh, Morris. 1962. "Linguistic relations across the Bering Strait." American Anthropologist 64, 1262–1291.

- Tailleur, O.G. 1959. "Plaidoyer pour le youkaghir, branche orientale de la famille ouralienne." Lingua 6, 403–423.

See also

External links

- Bibliography at Online Documentation of Kolyma Yukaghir by Irina Nikolaeva