Cambridge English Language Assessment

|

| |

| Established | 1913 |

|---|---|

| Type | Not-for-profit |

| Purpose | Examination board - qualifications for learners and teachers of English |

| Headquarters | Cambridge, UK |

Region served | Global - operating in 130 countries with 4 million+ candidates per year |

Membership | 40,000+ registered preparation centres |

Parent organization | Cambridge Assessment |

| Subsidiaries | CaMLA and the Admissions Testing Service |

| Website |

www |

Formerly called | University of Cambridge ESOL Examinations (Cambridge ESOL) / University of Cambridge Local Examinations Syndicate (UCLES) |

Cambridge English Language Assessment is part of the University of Cambridge and has been providing English language assessments and qualifications for over 100 years.[1]

The first Cambridge English examination, the Certificate of Proficiency in English (CPE), was launched in 1913. The 12-hour exam had just three candidates, all of whom failed.[2] One hundred years on, Cambridge English provides more than 20 exams for learners and teachers, which are taken by over 4 million people each year.[3]

Cambridge English Language Assessment contributed to the development of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) and its examinations are aligned with the CEFR levels.[4]

In 2010, Cambridge English Language Assessment and the English Language Institute Testing and Certificate Division of the University of Michigan agreed to form a not-for-profit collaboration known as CaMLA (Cambridge Michigan Language Assessments). This brings together two institutions with a long history of language assessment.

History

Timeline 1209–2013

- 1209 - University of Cambridge founded

- 1534 - Cambridge University Press founded

- 1858 - University of Cambridge Local Examinations Syndicate (UCLES) founded

- 1913 - Certificate of Proficiency in English (CPE) introduced: sat by three candidates

- 1939 - Lower Certificate in English (LCE) introduced (renamed First Certificate in English (FCE) in 1975)

- 1941 - Joint agreement with the British Council – British Council centres established

- 1943–47 - Preliminary English Test (PET) introduced (reintroduced in 1980)

- 1971 - Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) initiated

- 1988 - The Royal Society of Arts (RSA) Examination Board becomes part of UCLES

- 1989 - Specialist EFL research and evaluation unit established

- 1989 - IELTS launched (a simplified and shortened version of ELTS which had been launched in 1980)

- 1990 - Association of Language Testers in Europe (ALTE) founded

- 1991 - Certificate in Advanced English (CAE) introduced

- 1993 - Business English Certificates (BEC) launched

- 1994 - Key English Test (KET) introduced

- 1995 - University of Oxford Delegacy of Local Examinations (UODLE) becomes part of UCLES

- 1997 - Young Learner English Tests (YLE) introduced

- 2001 - CEFR published

- 2002 - UCLES EFL renamed University of Cambridge ESOL Examinations (Cambridge ESOL)

- 2002 - One million Cambridge ESOL exam candidates

- 2004 - Admission testing introduced (the Admission Testing Service joined Cambridge English Language Assessment in 2011)

- 2006 - International Legal English Certificate (ILEC) launched

- 2007 - International Certificate in Financial English (IFCE) launched

- 2010 - CaMLA established (Cambridge Michigan Language Assessments)

- 2013 - Cambridge ESOL renamed Cambridge English Language Assessment

- 2013 - Four million Cambridge English exam candidates[5]

Cambridge University’s examination board (UCLES)

The first Cambridge English exam was produced in 1913 by UCLES (University of Cambridge Local Examinations Syndicate).

UCLES had been set up in 1858 to provide exams to students who were not members of a university. There was a growing concern in Britain with standards of school education and the transition from secondary to tertiary-level education. A number of schools "petitioned the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge [to provide] means of comparing achievements of pupils across schools."[6]

The secondary education sector was still voluntary in nature. Without support from the state, it was logical to seek help from universities that were long established and widely admired. The University of Oxford and University of Cambridge, in particular, were “regarded as viable sources of supervision.”[7]

UCLES was invited to set exams and inspect schools with the aim of raising educational standards. The University of Oxford also created its own examination board: the University of Oxford Delegacy of Local Examinations (UODLE). UODLE and its partner, the Association of Recognised English Language Schools, merged with UCLES in 1995.[8]

The first UCLES examinations took place on 14 December 1858. The exams were designed to test for university selection and were taken by 370 candidates in British schools, churches and village halls. Candidates were required to ‘satisfy the examiners’ in the analysis and parsing of a Shakespeare text; reading aloud; dictation; and composition (on either the recently deceased Duke of Wellington; a well-known book; or a letter of application).[9]

Female candidates were accepted by UCLES on a trial basis in 1864 and on a permanent basis from 1867. Cambridge University itself did not examine female students until 1882 and it was not until 1948 that women were allowed to graduate as full members of the university.[10]

In the mid to late 19th century, UCLES exams were taken by candidates based overseas – in Trinidad (from 1863), South Africa (from 1869), Guyana and New Zealand (from 1874), Jamaica (from 1882) and Malaya (from 1891). Many of these candidates were children of officers of the British colonial service and exams were not yet designed for non-native speakers of English.[11]

The first Cambridge English exam

In 1913 UCLES created the first exam for non-native speakers of English – the Certificate of Proficiency in English (CPE). This may have been prompted by the development of English exams ‘for foreigners’ by other universities.[12]

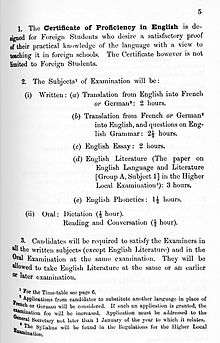

CPE was originally a qualification for teachers: ‘the Certificate of Proficiency in English is designed for Foreign Students who desire satisfactory proof of their knowledge of the language with a view to teaching it in foreign schools.’ The exam was only available for candidates aged 20 or over.[13]

In 1913 the exam could be taken in Cambridge or London, for a fee of £3 (approximately £293 in 2012 prices[14]). The exam lasted 12 hours and included:

- Translation from English into French or German: 2 hours

- Translation from French or German into English, and English Grammar: 2.5 hours

- English Essay: 2 hours

- English Literature: 3 hours

- English Phonetics: 1.5 hours

- Oral test: dictation (30 minutes); reading aloud and conversation (30 minutes)[15]

The main influence behind the design of the exam was the grammar-translation teaching approach, which aims to establish reading knowledge (rather than ability to communicate in the language). In 1913, the first requirement for CPE candidates was to translate texts. Translation remained prominent in foreign language teaching up until the 1960s. It was a core part of CPE until 1975, and an optional part until 1989.[16]

However, CPE was also influenced by Henry Sweet and his book published in 1900: A Practical Study of Languages: A Guide for Teachers and Learners, which argued that ‘the most natural method of teaching languages was through conversation.’ Due to this influence, speaking was part of Cambridge English exams from the very beginning.[17]

Exam questions in 1913

Candidates were required to translate from English into French/German, and translate from French/German into English. Here is a short segment from one of the passages candidates were asked to translate from English into German:

- The sentiments which animated Schiller’s poetry were converted into principles of conduct; his actions were as blameless as his writings were pure. With his simple and high predilections, with his strong devotedness to a noble cause, he contrived to steer through life, unsullied by its meanness, unsubdued by any of its difficulties or allurements …

In the English Essay paper, candidates were asked to write an essay for two hours, on one of the following subjects: the effect of political movements upon nineteenth century literature in England; English Pre-Raphaelitism; Elizabethan travel and discovery; the Indian Mutiny; the development of local self-government; or Matthew Arnold. The exam board provided little or no formal structure. Concepts such as audience and purpose, and the length of the essay, were left for the candidate to decide.

The questions in the English Literature section were borrowed from the University’s Language and Literature matriculation exams for native speakers and included questions on Shakespeare’s Coriolanus and Milton’s Paradise Lost. Here is an example question: explain fully and comment on the following passages, stating the connexions in which they occur and any difficulties of reading, phraseology or allusion: “Wert thou the Hector, That was the whip of your bragg’d progency, Thou should’st not ‘scrape me here.” It was not until 1930 that a Literature paper was designed specifically for CPE candidates.

The grammar section contained questions about grammar and lexis, e.g. give the past tense and past participle of each of the following verbs, dividing them into strong and weak …, and questions about grammar and lexis usage, e.g. embody each of the following words into a sentence in such a way as to show that you clearly apprehend its meaning: commence, comment, commend … At the time, this mirrored the approach to learning grammar in Latin and Greek (as well as modern languages).

Finally, a Phonetics paper was included as it was thought to be useful in the teaching of pronunciation. The paper required candidates to make phonetic transcriptions of long pieces of continuous text; describe the articulation of particular sounds; explain phonetic terms, and suggest ways of teaching certain sounds. Here are two example questions: explain the terms: “glide”, “narrow vowel”, “semi-vowel” and give two examples of each in both phonetic and ordinary spelling and how would you teach a pupil the correct pronunciation of the vowel sounds in: fare, fate, fat, fall, far?

Revisions to the 1913 exam

The 1913 CPE exam was taken by just three candidates. The candidates "were able to converse fluently, expressing themselves on the whole, with remarkable ease and accuracy." However, all three candidates failed the exam and none of them were awarded a CPE certificate.[18]

In its second year (1914), CPE gained in popularity, with 18 candidates and four passing. However, for the next 15 years candidature remained static.[19] Italian and Spanish were added as languages for the translation paper in 1926. However, CPE still ‘teetered along with 14 or 15 candidates a year.’ In 1928, CPE had only 14 candidates and by 1929 it was in danger of being discontinued.[20]

Jack Roach, Assistant Secretary to the Syndicate from 1925 to 1945, decided to "save it from the scrapheap" and introduced a number of changes.[21] The Phonetics paper was dropped and the essay questions became more a test of writing proficiency rather than a test of knowledge about British culture. Questions such as "The best month of the year" were preferred to the more culture-bound topics set in 1913, such as "Elizabethan travel and discovery."[22]

The target candidature was broadened beyond teachers, to "all foreign students who desire to obtain evidence of their practical knowledge of the languages, both written and spoken, as of their ability to read with comprehension standard works of English literature."

In 1932 it was decided to establish overseas exam centres. The first overseas centres were set up in Hamburg, Paris and San Remo (1933), followed by further centres in Italy (Rome and Naples), the Netherlands, Sweden and Switzerland. Latin America also became an exam area in the 1930s, with centres in Argentina and Uruguay.

In 1935 CPE started providing alternatives to the Literature paper, with an Economic and Commercial Knowledge paper – an early forerunner of English for Specific Purposes.

Then, in 1937–38, the University of Cambridge and University of Oxford decided to accept CPE as representing the standard in English required of all students, British or foreign, before entrance to their university. To this day, CPE still serves as a qualification for entry to higher education. Following these changes CPE candidate numbers instantly began to rise, reaching 752 by the outbreak of World War II.[23]

World War II

From 1939 onwards, thousands of refugees from the Spanish Civil War and occupied Europe started arriving in the UK and began taking UCLES exams while stationed in the UK.

UCLES launched the Lower Certificate in English (LCE) to meet the demand for certification at a lower level than CPE. A Preliminary exam, at a lower level than LCE, was also offered from 1944 as a special test to meet the contingencies of war. These were the first steps towards developing a language assessment ‘level’ system.

Polish servicemen and women made up a large proportion of the candidature. In 1943, over a third of all LCE Certificates were awarded to candidates from the Polish army and air force. This pattern continued throughout the war and into the post-war period. On one single day in 1948, no fewer than 2,500 Polish men and women of the Polish Resettlement Corps took the LCE.

UCLES tests were made available for prisoners of war in Britain and in Germany. In Britain 1,500 prisoners of war took the exams, almost 900 of them Italians. In Germany, the War Organisation of the British Red Cross and Order of St John of Jerusalem made arrangements for UCLES examinations to be offered at prisoner-of-war camps with many Indian prisoners of war, in particular, taking LCE or School Certificate exams.

Examiners were asked to report on "disturbance, loss of sleep, etc., caused by air raids, and on any exceptional difficulties … during the examination period." One report noted that the candidates had been spending "most of each day in the air-raid shelter"; that candidate 5224, a probationer nurse, had been showing strain caused by helping with "rescue work"; and that the house of candidate 5222 had been bombed, whilst she was at school, with fatalities. Such were the circumstances of wartime exam takers and administrators.

Exams were also maintained clandestinely in continental European exam centres, which frequently meant unusual measures, including acts of determination and courage. However, UCLES was unable to fund and support the growing international network of English language examination centres around the world. Meanwhile, the British Council had a brief to disseminate British culture and educational links. In March 1941 a formal ‘Joint Agreement’ was signed between the two organisations to collaborate on the distribution of UCLES exams around the world. This started a long-lasting relationship, which continues to this day.[24]

Post-war

By 1947, there were over 6,000 UCLES candidates, with LCE double the size of CPE. Exam centres had been set up in Europe (17), Latin America (9), the Middle East (8), Africa (4) and the USA (1). Candidate numbers continued to grow, reaching over 20,000 by 1955, 44,000 by 1965, and over 66,000 by 1975.

However, by the 1970s demand was growing for exams at more clearly defined levels of proficiency. This set the scene for the Council of Europe and the development of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR), which was initiated in 1971.

Qualification developments – the level system

UCLES had a few attempts at developing a level system. During the Second World War, there was a three-level system: the Preliminary English Test, LCE and CPE. After the war, a new three-level system was introduced: LCE, CPE and DES (The Diploma of English Studies). However, as an extremely advanced exam, DES candidature never rose beyond a few hundred and was later ‘quietly removed’. In the 1980s and 1990s the levels stabilised and the suite of exams we recognise today slowly became established.

First, UCLES explored the viability of an exam below LCE (renamed as First Certificate in English). The Preliminary English Test (PET) (re)appeared in 1980 under close monitoring, and as a fully-fledged exam in the 1990s.

UCLES then explored the viability of an exam at a level between FCE and CPE and the Certificate in Advanced English (CAE) was formally launched in 1991.

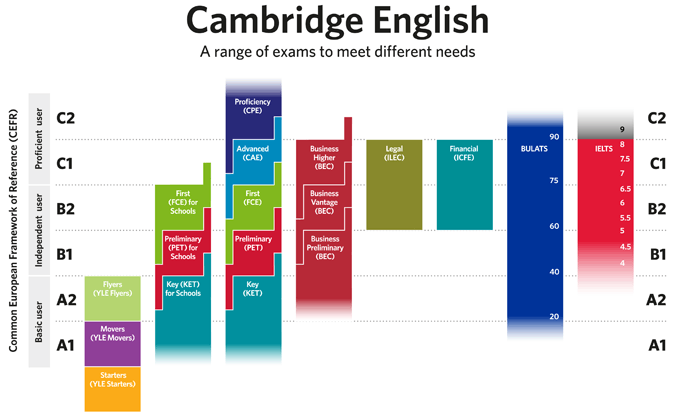

Finally, in 1994, UCLES launched the Key English Test (KET). This five-level system characterises Cambridge English’s General English exams to the present day and laid the foundations for the levels in the CEFR.

- Level 1: Cambridge English: Key (KET) (CEFR level A2: waystage)

- Level 2: Cambridge English: Preliminary (PET) (CEFR level B1: threshold)

- Level 3: Cambridge English: First (FCE) (CEFR level B2: vantage)

- Level 4: Cambridge English: Advanced (CAE) (CEFR level C1: operational proficiency)

- Level 5: Cambridge English: Proficiency (CPE) (CEFR level C2: mastery)[25]

During this period there were also substantial revisions to the existing exams: FCE and CPE. These revisions included improved authenticity of texts and tasks; increased weight on Listening and Speaking; a balance between grammar and vocabulary items in the Reading paper; and a broader range of texts in the Composition and Use of English papers, (e.g. letter-writing, dialogues, speeches, note-taking, and discursive and descriptive compositions).

With increased weight on Listening and Speaking, UCLES joined forces with the BBC. However, in the BBC recording booths, there was tension between the BBC’s approach, which focused on dramatic potential, and UCLES’ need for clarity of speech. For example, a man abseiling down a mountain was highly entertaining but unacceptable for test purposes. It was finally agreed that at least 35% of listening tests would comprise an original BBC recording, largely made up of programmes from World Service and Women’s Hour broadcasts.[26]

IELTS

With learners increasingly requiring English language certification for their studies, UCLES, along with the British Council and the Australian International Development Programme (IDP), developed a test in the 1980s which focused specifically on English for academic purposes, as does the American TOEFL.

An English Language Testing Service (ELTS) test was first launched in 1980 with tasks based on language use in academic and occupational contexts in the ‘real world’. However, the ELTS test was very complex to administer and only two full versions were ever produced. In 1989, a simplified and shortened test became operational under a new name: the International English Language Testing System (IELTS).[27]

It was clear that different forms of the test would need to be equated. All IELTS materials were therefore pretested and calibrated to a common scale on the basis of the Rasch model. This was the first time that UCLES had used the Rasch model, which now forms the cornerstone of the level testing system.[28]

RSA and teaching qualifications

In 1988, the EFL exams developed by The Royal Society of Arts (RSA) Examination Board were merged with those of UCLES. The RSA Examination Board had been established in 1754, long before UCLES, and by taking over the RSA TEFL schemes UCLES became responsible for "the running of the world’s most respected and widely recognised schemes for validating training courses for teachers of English as a Foreign Language."[29]

The two sets of qualifications were integrated and syllabuses for the revised qualifications were developed in consultation with the ESL sector, in order to re-integrate the ESL and EFL teacher communities. In 1999 the RSA Certificate in Teaching English as a Foreign Language to Adults (CTEFLA) and the RSA Diploma in Teaching English as a Foreign Language to Adults officially became known as the CELTA and Delta qualifications. These qualifications were joined in 2004 by ICELT (a revised version of its predecessor, COTE) – which is a purely in-service professional qualification.

At the start of the 21st century there was growing demand from government ministries and schools for a professional qualification without any in-service (teaching practice) component. This led to the introduction of the Teaching Knowledge Test (TKT), which focuses solely on core professional knowledge. Following consultations with worldwide teacher training institutions and trials with 1,500 English language teachers in Europe, Latin America and Asia, TKT went live in 2005. In the first six months thousands of candidates sat the test in 36 different countries. It was also incorporated into government plans, e.g. plans in Chile to retrain all in-service teachers, and was incorporated into state university teacher training programmes.[30]

China and business English

The early 1990s saw China developing its market economy very rapidly. Recognising the importance of English as a language of international business and trade, the Chinese government asked UCLES to develop a suite of Business English Certificates (BEC).

BEC 1 examinations were first taken in 1993 by 5,000 candidates from seven cities across China, with BEC 2 launched in 1994 and BEC 3 in 1996. BEC was followed in 1997 by the launch of the Business Language Testing Service (BULATS) for companies, which tests English, French, German and Spanish proficiency in the workplace.[31]

Since the turn of the century there has been demand for business English specific to professional domains. Cambridge worked with lawyer-linguist firm TransLegal to develop the International Legal English Certificate (ILEC), launched in 2006.[32] Then in 2007, the International Certificate in Financial English (ICFE) was launched in collaboration with the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA), the global body for professional accountants.[33]

Young learners

In the 1990s, there was growing demand from UCLES centres in the Far East, Latin America and Europe for assessment designed specifically for younger learners. At the time, relatively little research had been carried out into the assessment of second language learning in children. UCLES worked with Homerton College (a teacher training college, now a college within the University of Cambridge) to trial test questions with over 3,000 children in Europe, South America and South East Asia. The feedback was used to construct the first Young Learners English (YLE) tests, targeted at learners aged 7–12, which went live in 1997.The YLE tests introduced a new level: ‘breakthrough’ level. ‘Breakthrough’ became the new first level, with ‘waystage’ now the second level. The addition of the ‘breakthrough’ level created a six-level system that was mirrored by the CEFR, published in 2001.[34]

Admissions Testing Service

In 2001 an admissions test, Thinking Skills Assessment (TSA), was introduced for entry to a range of undergraduate courses at the University of Cambridge, and in 2004 a dedicated unit was set up to develop and administer admissions tests for universities and businesses - the Admissions Testing Service.[35]

Fuelled by the Schwartz Report (2004) about fair admissions to higher education, the unit explored whether a single test (uniTEST) could be used for admission to a broad range of subjects and institutions. However, there was little demand in the UK higher education sector. Instead other projects followed, leading to a range of subject-specific admissions test, thinking skills and behavioural styles assessments, and tests for the medicine and healthcare sector. The Admissions Testing Service formally joined Cambridge English Language Assessment in 2011.[36]

Candidates

By the start of the 21st century, most of the Cambridge exam suite, which we recognise today, was established. This set the scene for massive growth in candidates.

In 1988, with just two established exams (FCE and CPE), exam candidature was around 180,000. By 2002, with a more comprehensive range of exams, the exam candidature was over 1 million; by 2007, it was over 2 million and by 2013, it was over 4 million. In particular, IELTS has recorded some of the fastest growth. In 2002 there were 212,000 candidates, whereas today there are more than 2 million candidates annually.[37]

Individual exams

English for Young Learners

The Cambridge English: Young Learners (YLE) tests are designed for young learners in primary and lower secondary education who are taking their first steps in English. The tests include tasks designed to motivate young children, such as drawing, colouring and solving puzzles.[38]

| Exams | CEFR level | Exam description |

|---|---|---|

| Cambridge English: Starters (YLE Starters) | Pre-level A1 | Learners will learn basic sentences, vocabulary, letters and numbers. |

| Cambridge English: Movers (YLE Movers) | A1 | Learners will read simple stories, take part in basic, factual conversations and write simple sentences using words provided. |

| Cambridge English: Flyers (YLE Flyers) | A2 | Learners will understand longer texts, communicate with English speakers who talk slowly and clearly, and write short messages on a postcard or in an email. |

General English and for Schools

Cambridge English: Key (KET), Cambridge English: Preliminary (PET) and Cambridge English: First (FCE) are designed for learners who need English for work, study and travel. They also help learners working towards higher level qualifications such as Cambridge English: Advanced (CAE) and Cambridge English: Proficiency (CPE). The qualifications are offered in two versions: for adult learners and for school-aged learners in lower and upper secondary school education. Both versions lead to the same qualification. The only difference is that the topics in the ‘for Schools’ version are targeted at the interests and experiences of school-aged learners.[39]

Cambridge English: Advanced (CAE) has become a natural exit level for many school learners, due to ever-growing demands for English language proficiency and is accepted around the world for higher education study, work and migration purposes. Students with a Cambridge English: Advanced (CAE) certificate gain exemption from the English components of school-leaving exams in countries such as Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia and Ukraine.[40] Cambridge English: Proficiency (CPE) is also available for exceptional school learners with the ability to use English at near-native levels.

| Exams | CEFR level | Exam description |

|---|---|---|

| Cambridge Young Learners English Tests |

|

For learners in primary and lower secondary school education who are taking their first steps in English. |

| Cambridge English: Key (KET) and Cambridge English: Key for Schools (KET) | A1-B1 | An elementary level qualification. It covers basic practical English, such as understanding simple questions, instructions and phrases, expressing simple opinions and needs, interacting with English speakers who talk slowly, completing forms and writing short messages. |

| Cambridge English: Preliminary (PET) and Cambridge English: Preliminary for Schools (PET) | A2-B2 | An intermediate level qualification. It covers everyday, practical English, such as understanding straightforward instructions and public announcements, taking part in factual conversations, writing letters and making notes. |

| Cambridge English: First (FCE) and Cambridge English: First for Schools (FCE) | B1-C1 | An upper-intermediate qualification. It covers use of English in real-life situations and study environments. Learners are expected to understand the main ideas of complex texts taken from a range of sources (such as magazines, news articles and fiction), demonstrate different writing styles (such as emails, essays, letters or short stories), follow a range of spoken materials (such as news programmes and public announcements), and keep up in conversations on a wide range of topics, expressing opinions, presenting arguments and producing spontaneous spoken language. |

| Certificates in ESOL Skills for Life (SfL) (UK only) | A1-C1 | Qualifications for learners aged 16 and over who live in England, Wales or Northern Ireland. The qualifications are based on the UK government’s Adult ESOL Core Curriculum. Cambridge English: ESOL Skills for Life aims to help learners use English in everyday work and life situations. Test topics may include work, health, leisure, education and training, shopping, transport and housing. |

Academic and Professional English

Cambridge English: First (FCE), Cambridge English: Advanced (CAE), Cambridge English: Proficiency (CPE) and IELTS are all commonly used as proof of English language proficiency for academic study, migration, professional registration and employment.

| Exams | CEFR level | Exam description |

|---|---|---|

| Cambridge English: First (FCE) | B1-C1 | An upper-intermediate qualification. Learners use this qualification for study in English at foundation or pathway level and to work in English-speaking business environments. |

| Cambridge English: Advanced (CAE) | B2-C2 | A qualification for high achievers. Learners use this qualification for undergraduate or graduate-level study and to work at professional or managerial level in international business. Cambridge English: Advanced (CAE) demonstrates that a learner has the English language skills needed to follow any undergraduate academic course, participate in academic tutorials and seminars, carry out complex research and communicate effectively at a managerial level in an international business setting. |

| Cambridge English: Proficiency (CPE) | C1-C2 | A qualification which demonstrates proof of exceptional English ability and ability to use English at near-native levels in a wide range of situations. Learners use this qualification to study postgraduate academic courses, lead high-level research projects and academic seminars and communicate effectively at an upper managerial and board level in international business. |

| IELTS (International English Language Testing System) | A1-C2 | The world’s most popular English language test for higher education and global migration. IELTS is accepted by over 8,000 institutions, employers and government bodies worldwide, including thousands of universities and colleges in the USA which use it as a standard entrance requirement.

IELTS is managed by an international partnership of not-for-profit organisations – the British Council, Cambridge English Language Assessment and IDP: IELTS Australia – and is administered through more than 400 test centres in 150 countries worldwide. |

Business English

Cambridge English: Business Certificates (BEC), Cambridge English: Financial, Cambridge English: Legal and BULATS are assessments set in a business context that test use of English in practical, everyday situations. Cambridge English also provides assessments for the medical and healthcare sector, e.g. the Occupational English Test (described in the Admissions Test section).

| Exams | CEFR level | Exam description |

|---|---|---|

| Cambridge English: Business Certificates |

|

Qualifications for professionals who want to work in an international business environment. Learners will learn to:

|

| Cambridge English: Financial (ICFE) (to be discontinued in December 2016) | B2-C1 | A qualification for finance professionals working in an international business environment. Topics might include: banking, bankruptcy, financial reporting, acquisitions and mergers, company financial strategy, debt recovery and credit policy, insurance, corporate governance, budgetary processes, ethics and professionalism, costs and management accounting, environmental and sustainability issues, auditing, investment banking, forensic accounting, accounting software packages, assets and company valuations, risk assessment and analysis.[42] |

| Cambridge English: Legal (ILEC) (to be discontinued in December 2016) | B2-C1 | A qualification produced in collaboration with the TransLegal Group, aims to demonstrate to employers and clients that an individual has the English language skills to work in a legal environment. Areas of law typically covered include corporate; business associations; contract; sale of goods; real property; debtor-creditor; intellectual property; employment; competition; environmental; negotiable instruments; secured transactions; aspects of transnational law.[43] |

| BULATS | A1-C2 | A language assessment service for companies, developed and delivered by Cambridge English Language Assessment in collaboration with Alliance Française, Goethe-Institut and Universidad de Salamanca. BULATS assesses workplace language skills in English, French, German and Spanish. The BULATS Benchmarking service helps organisations establish what levels of language ability are needed for different jobs and the BULATS Preparation Courses support learners with their study and test preparation. The BULATS tests assess all four skills (reading, writing, speaking and listening) in a business context and scores are reported at the appropriate CEFR level. |

Admissions Tests

The Admissions Testing Service (part of Cambridge English Language Assessment) supports education institutions, businesses and governments in the recruitment of candidates and professional registration.

The service provides medicine and healthcare admissions tests (OET, BMAT and IMAT), assessments in thinking skills, behavioural styles and values (TSA and CPSQ) and subject-specific aptitude tests (ELAT and STEP). The Admissions Testing Service also administers universities’ own admissions tests, e.g. admissions tests developed by the University of Oxford.[44]

| Exams | Test type |

|---|---|

| Occupational English Test (OET) | Medicine and healthcare |

| BioMedical Admissions Test (BMAT) | Medicine and healthcare |

| International Medical Admissions Test (IMAT) | Medicine and healthcare |

| English Literature Admissions Test (ELAT) | Subject-specific test |

| Sixth Term Examination Paper (STEP) | Subject-specific test |

| Thinking Skills Assessment (TSA) | Thinking skills test |

| Cambridge Personal Styles Questionnaire (CPSQ) | Behavioural styles assessment |

Teaching qualifications

| Exams | Teaching level on the Cambridge English Teaching Framework | Who is it for | Course delivery |

|---|---|---|---|

| CELTA (Certificate in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages) | Foundation/Developing | CELTA is an initial teaching qualification for new teachers or people teaching without a formal teaching qualification. | Full time/part time. Face-to-face course or online course with face-to-face teaching practice. |

| Young Learner Extension to CELTA (to be discontinued December 2016) | Developing | Teachers with CELTA who wish to develop the skills and confidence to teach English to children and teenagers. | Full time/part time. Face-to-face course or online course with face-to-face teaching practice. |

| CELT-P (Certificate in English Language Teaching – Primary) | Foundation/Developing | Schools or governments who want to support the development of their English language teachers working in primary schools (ages 4–11). | Online modular course with optional face-to-face elements. Assessed through an exam and teaching practice. |

| CELT-S (Certificate in English Language Teaching – Primary) | Foundation/Developing | Schools or governments who want to support the development of their English language teachers working in secondary schools (ages 12–19). | Online modular course with optional face-to-face elements. Assessed through an exam and teaching practice. |

| Language for Teaching | Foundation/Developing/Proficient | Schools or governments who want to support their English language teachers to improve their English to reach CEFR levels A2, B1 or B2. | Online learning with optional face-to-face elements. |

| TKT (Teaching Knowledge Test) | Foundation/Developing | New teachers and existing teachers who want their EFL teaching knowledge formally recognised with an international qualification. | Exams with a flexible modular format. |

| ICELT (In-service Certificate in English Language Teaching) | Developing/Proficient | Existing teachers who want to develop their English teaching skills and knowledge while they work. | Part time face-to-face course with teaching practice and distance learning support. |

| Delta (Diploma in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages) | Proficient/Expert | Experienced teachers looking to update their teaching knowledge, improve their practice and seek career progression. It is the same level as a master’s degree or a professional diploma in the UK. | Flexible modular format combining coursework and exams. Distance learning support, local tutoring and assessed teaching practice. |

| IDLTM (International Diploma in Language Teaching Management) | Proficient/Expert | Experienced teachers who want to move into management roles. | Full time face-to-face introductory course, followed by flexible distance learning. |

| Certificate in EMI Skills (English as a medium of instruction) | Proficient/Expert | Academic staff working in English-taught higher education whose first language is not English. | Online learning with optional face-to-face sessions. |

| Train the Trainer | Proficient/Expert | Experienced teachers who want to train other teachers for the CELT-P, CELT-S or Language for Teaching courses. | Part time face-to-face course. |

Discontinued exams

- CELS (Certificates in English Language Skills): these modular qualifications for English language learners (now discontinued) allowed students to prove what they could do in each skill (reading, writing, speaking, and listening) and certificated each skill separately.

- DTE(E)LLS (Diploma in Teaching English (ESOL) in the Lifelong Learning Sector) and ADTE(E)LLS (Additional Diploma in Teaching English (ESOL) in the Lifelong Learning Sector): these qualifications for English language teachers in the UK were discontinued in September 2012. CELTA is a recommended alternative for those wanting an English teaching qualification for teaching in the UK.

- PTLLS (Preparing to Teach in the Lifelong Learning Sector): this was discontinued in November 2012 following the UK government’s withdrawal of the Level 4 PTLLS Award from the National Qualifications Framework.

CaMLA

Cambridge Michigan Language Assessments (CaMLA) was established in 2010 by Cambridge English Language Assessment and the English Language Institute Testing and Certificate Division of the University of Michigan – two organizations with a long history in English language assessment. The organizations have a number of other similarities: both university-based, not-for-profit exam boards, with a mission to support research and learning.

CaMLA was created as a joint venture to develop the Michigan tests and services, originally established by the English Language Institute (ELI) of the University of Michigan. It is therefore building on 70 years of research and development at Michigan in language teaching, learning, assessment, applied linguistics and teacher education throughout the world.[45]

Alignment with the Common European Framework of Reference for Language (CEFR)

The CEFR is a series of descriptions of abilities which can be applied to any language. The descriptors are used to help define language proficiency levels and to interpret language qualifications. The CEFR has become accepted as a way of benchmarking language ability not only within Europe but worldwide.

Cambridge English Language Assessment was involved in the early development of the Common European Framework for Reference for Languages (CEFR) and all of Cambridge English examinations are aligned with the levels described by the CEFR.

Cambridge English’s suite of level-based exams target particular levels of the CEFR and candidates are encouraged to take the exam most suitable to their needs and level of ability. However, while each level-based exam focuses on a particular CEFR level, the exam also contains test material at the adjacent levels (e.g. Cambridge English: First (FCE) is aimed at B2, but there are also test items that cover B1 and C1). This allows for inferences to be drawn about candidates’ abilities if they are a level below or above the one targeted.

A1 is the level of those first beginning to learn a language. Some awards are mapped onto this level, including Cambridge English: Young Learners (YLE), and Entry 1 in Certificates in ESOL Skills for Life. However, candidates would receive 1.0 for IELTS, or 0 for BULATS, if they left the testing papers blank. Thus scores of 1.0 for IELTS, or 0 for BULATS, should not be treated as an ‘award’ at A1 level.

As it became increasingly important to verify claims of alignment to the CEFR, Cambridge English Language Assessment contributed to the authoring and piloting of the Council of Europe’s Manual for Relating Language Examinations to the CEFR. The Manual’s linking process is based on three sets of procedures: specification; standardisation; empirical validation. These alignment procedures are embedded within the test development and validation cycle of all Cambridge English exams.[46]

Research

As a department of the University of Cambridge, Cambridge English Language Assessment shares the university's mission to "contribute to society through the pursuit of education, learning and research at the highest international levels of excellence."[47] The Cambridge English EFL Evaluation Unit was established in 1989 and was the first dedicated research unit of its kind. This unit is now called the Research and Validation Group and is the largest dedicated research team of any English language assessment body.[48]

The Research and Validation Group carries out research on issues of comparability, validity and reliability. Research is published in the Studies in Language Testing (SiLT) series.[49]

It contributed to the original development of the Council of Europe's Common European Framework of References for Languages (CEFR) and continues to support the development of the CEFR through new projects. This includes the English Profile project which is developing practical descriptions of how learners can be expected to use English at each of the six levels of the CEFR. And the European Commission SurveyLang project, which is supporting the development of language learning policies across Europe.

Awards

Cambridge English Language Assessment has been awarded the Queen’s Award for Enterprise in the 'international trade' category.[50]

See also

- Admissions Testing Service

- CaMLA

- IELTS, International English Language Testing System

- Studies in Language Testing (SiLT)

- Teaching English as a Foreign Language

References

- ↑ http://www.cambridgeenglish.org/about-us/who-we-are/cambridge-assessment/ Retrieved 7 January 2014

- ↑ http://www.upbo.com/servlet/file/store6/item2373702/version1/item_9780521013314_excerpt.pdf Retrieved 7 January 2014

- ↑ http://www.cambridgeenglish.org/about-us/what-we-do/ Retrieved 7 January 2014

- ↑ http://www.cambridgeenglish.org/research-and-validation/fitness-for-purpose/ Retrieved 7 January 2014

- ↑ Hawkey, R; Milanovic, M (2013), Cambridge English Exams. The first hundred years, retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ↑ Bradbury, R (1983) Magazine of the Cambridge Society, 13, 31–38

- ↑ Roach, J (1971) Public Examinations in England, 1850–1900

- ↑ http://www.uodle.org.uk/ Retrieved 7 January 2014

- ↑ Morris, M (1961) A historian’s view of examinations, in Wiseman, S (Ed), Examinations and English Education, Manchester: University of Manchester, 1–43

- ↑ Chambers, S (1998) At last, a degree of honour for 900 Cambridge women, The Independent. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/at-last-a-degree-of-honour-for-900-cambridge-women-1157056.html Retrieved 9 September 2012

- ↑ Hawkey, R, Milanovic, M (2013) Cambridge English Exams. The first hundred years

- ↑ http://www.upbo.com/servlet/file/store6/item2373702/version1/item_9780521013314_excerpt.pdf Retrieved 7 January 2014

- ↑ UCLES, 1913, Regulations for the Examination for Certificates of Proficiency in Modern Language and Religious Knowledge

- ↑ http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/education/Pages/inflation/calculator/flash/default.aspx Retrieved 7 January 2014

- ↑ http://www.cambridgeenglish.org/images/23124-research-notes-10.pdf Retrieved 7 January 2014

- ↑ Howatt, A (1984) A history of English Language Teaching, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- ↑ Hawkey, R, Milanovic, M (2013) Cambridge English Exams. The first hundred years.

- ↑ University of Cambridge (1913), Class List and Supplementary Tables for the June 1913 University of Cambridge Higher Local Examination and Examination for Certificates of Proficiency in Modern Languages and Religious Knowledge.

- ↑ Hawkey, R, Milanovic, M (2013) Cambridge English Exams. The first hundred years

- ↑ Roach, J O (1956) Part copy of JOR’s report on Examinations as an instrument of cultural policy. Cambridge Assessment Archives

- ↑ Roach, J O (1956) Part copy of JOR’s report on Examinations as an instrument of cultural policy. Cambridge Assessment Archives

- ↑ http://www.upbo.com/servlet/file/store6/item2373702/version1/item_9780521013314_excerpt.pdf Retrieved 7 January 2014

- ↑ Hawkey, R, Milanovic, M (2013) Cambridge English Exams. The first hundred years.

- ↑ Hawkey, R, Milanovic, M (2013) Cambridge English Exams. The first hundred years

- ↑ http://www.topbooks.pl/store/31/3113080856344df7cd82d18cb.pdf, Page 8. Retrieved 7 January 2014

- ↑ Hawkey, R, Milanovic, M (2013) Cambridge English Exams. The first hundred years

- ↑ http://www.ielts.org/researchers/history_of_ielts.aspx Retrieved 7 January 2014

- ↑ McNamara, Tim; Knoch, Ute. (2012). The Rasch wars: The emergence of Rasch measurement in language testing. Language Testing. v29 n4 p555-576. DOI: 10.1177/0265532211430367

- ↑ Hargreaves, P (1996), ELT News and Views, Argentina

- ↑ http://www.britishcouncil.org/srilanka-learning-tkt-development-report.pdf Retrieved October 2013

- ↑ http://www.cambridgeenglish.org/images/23120-research-notes-08.pdf Retrieved 7 January 2014

- ↑ http://www.translegal.com/our-history Retrieved 7 January 2014

- ↑ http://www2.accaglobal.com/allnews/students/2007/NEWSQ1/News/2890778 Retrieved 7 January 2014

- ↑ http://www.cambridgeenglish.org/images/23119-research-notes-07.pdf Retrieved 7 January 2014

- ↑ http://www.admissionstestingservice.org/our-services/thinking-skills/tsa-cambridge/about-tsa-cambridge/ Retrieved 7 January 2014

- ↑ Hawkey, R, Milanovic, M (2013) Cambridge English Exams. The first hundred years

- ↑ Hawkey, R, Milanovic, M (2013) Cambridge English Exams. The first hundred years

- ↑ http://www.cambridgeenglish.org/exams-and-qualifications/young-learners/ Retrieved 7 January 2014

- ↑ http://www.cambridgeenglish.org/exams-and-qualifications/ Retrieved 7 January 2014

- ↑ http://www.cambridgeenglish.org/images/139661-cae-information-for-students.pdf Retrieved 7 January 2014

- ↑ http://www.cambridgeenglish.org/why-cambridge-english/visas-and-immigration/uk/ Accessed 08 July 2015

- ↑ http://www.britishcouncil.org/uae-exams-cambridge-icfe.htm Retrieved 7 January 2014

- ↑ http://www.britishcouncil.org/uae-cambridge-professional-ilec-information.pdf Retrieved 7 January 2014

- ↑ http://www.admissionstestingservice.org/images/127141-the-admissions-testing-service-a-brief-guide.pdf Retrieved 7 January 2014

- ↑ http://www.ur.umich.edu/update/archives/100927/english Retrieved 17 June 2015

- ↑ http://www.cambridgeenglish.org/research-and-validation/fitness-for-purpose Retrieved 7 January 2014

- ↑ https://www.cam.ac.uk/about-the-university/how-the-university-and-colleges-work/the-universitys-mission-and-core-values Accessed 05 September 2015

- ↑ Hawkey, R, Milanovic, M (2013) Cambridge English Exams. The first hundred years

- ↑ http://centenary.cambridgeenglish.org/timeline/1989-efl-evaluation-unit/ Retrieved 7 January 2014

- ↑ http://www.cambridgeassessment.org.uk/news/cambridge-english-wins-queens-award-for-enterprise/

External links

- Cambridge English Language Assessment Website

- Cambridge English Candidate Support Site

- Cambridge English Teacher Support Site

- Studies in Language Testing (SiLT)

- Admissions Testing Service (ATS)

- SurveyLang

- English Profile

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|