United States v. Jones (2012)

| United States v. Antoine Jones | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Argued November 8, 2011 Decided January 23, 2012 | |||||||

| Full case name | United States v. Antoine Jones | ||||||

| Docket nos. | 10-1259 | ||||||

| Citations |

132 S. Ct. 945, 181 L. Ed. 2d 911 | ||||||

| Prior history | Motion to suppress evidence rejection, 451 F.Supp.2d 71 (D.D.C. 2006); motion for reconsideration denied, 511 F.Supp.2d 74 (D.D.C. 2007); reversed sub nom. United States v. Maynard, 615 F.3d 544 (D.C. Cir. 2010); rehearing en banc denied, 625 F.3d 766 (2010); certiorari granted, 564 U.S. ___ (2011). | ||||||

| Argument | Oral argument | ||||||

| Holding | |||||||

| The Government's attachment of the GPS device to the vehicle, and its use of that device to monitor the vehicle's movements, constitutes a search under the Fourth Amendment. DC Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed. | |||||||

| Court membership | |||||||

| |||||||

| Case opinions | |||||||

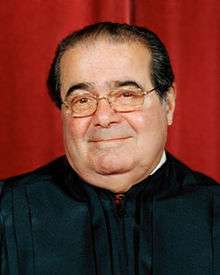

| Majority | Scalia, joined by Roberts, Kennedy, Thomas, Sotomayor | ||||||

| Concurrence | Sotomayor | ||||||

| Concurrence | Alito, joined by Ginsburg, Breyer, Kagan | ||||||

| Laws applied | |||||||

| U.S. Const. amend. IV | |||||||

United States v. Jones, 132 S. Ct. 945, 565 U.S. ___ (2012), was a United States Supreme Court case which held that installing a Global Positioning System (GPS) tracking device on a vehicle and using the device to monitor the vehicle's movements constitutes a search under the Fourth Amendment.

In 2004 defendant Jones was suspected of drug trafficking. Police investigators asked for and received a warrant to attach a GPS tracking device to the underside of the defendant's car but then exceeded the warrant's scope in both geography and length of time. The Supreme Court justices voted unanimously that this was a "search" under the Fourth Amendment, although they were split 5-4 as to the fundamental reasons behind that conclusion. The majority held that by physically installing the GPS device on the defendants car, the police had committed a trespass against Jones' "personal effects" – this trespass, in an attempt to obtain information, constituted a search per se.

Background

Police investigation and criminal trial

Antoine Jones owned a nightclub in the District of Columbia; Lawrence Maynard managed the club. In 2004, a joint Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and Metropolitan Police Department task force began investigating Jones and Maynard for narcotics violations.[1] During the course of the investigation, a Global Positioning System (GPS) device was installed on Jones's Jeep Grand Cherokee[2] without a valid warrant.[3] This device tracked the vehicle's movements 24 hours a day for four weeks.[4] The FBI arrested Jones in late 2005, at which time Jones was represented by criminal defense attorney A. Eduardo Balarezo of Washington, D.C. Balarezo filed multiple motions on Jones' behalf, including the motion to suppress the GPS data. This motion formed the basis for Jones' appeals. The government tried Jones for the first time in late 2006, and after a trial lasting over a month, a federal jury deadlocked on the conspiracy charge and acquitted him of multiple other counts. The government retried Jones in late 2007, and in January 2008 the jury returned a guilty verdict on one count of conspiracy to distribute and to possess with intent to distribute five or more kilograms of cocaine and 50 or more grams of cocaine base.[5] He was sentenced to life in prison.[6]

Appeal

Jones argued that his conviction should be overturned because the use of the GPS tracker violated the Fourth Amendment's protection against unreasonable search and seizure.[7] In August 2010, the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit overturned Jones's conviction, holding that the police action was a search because it violated Jones's "reasonable expectation of privacy".[8] The court's decision was the subject of significant legal debate.[9][10] In June 2011, the Supreme Court granted a petition for a writ of certiorari to resolve two questions. The first question, briefed by the parties in their initial petition for certiorari was "Whether the warrantless use of a tracking device on respondent's vehicle to monitor its movements on public streets violated the Fourth Amendment." The second question, which the Court directed the parties to brief in addition to the initial question, was "Whether the government violated respondent's Fourth Amendment rights by installing the GPS tracking device on his vehicle without a valid warrant and without his consent"[11]

Oral argument

Deputy Solicitor General Michael R. Dreeben[12] began his argument for the United States by noting that information revealed to the world (i.e. movement on a public road) is not protected by the Fourth Amendment.[13] Dreeben cited United States v. Knotts as an example where police were allowed to use a device known as a "beeper" that allows the tracking of a car from a short distance away.[13] Chief Justice Roberts distinguished the current case from Knotts, saying that using a beeper still took "a lot of work" whereas a GPS device allows the police to "sit back in the station ... and push a button whenever they want to find out where the car is."[14]

Justice Scalia then directed the discussion to whether installing the device was an unreasonable search. Scalia argued that "when that device is installed against the will of the owner of the car on the car, that is unquestionably a trespass and thereby rendering the owner of the car not secure in his effects... against an unreasonable search and seizure."[15] Dreeben argued that it was a trespass, but in United States v. Karo there was also a trespass and, according to Dreeben, Karo held that it "made no difference because the purpose of the Fourth Amendment is to protect privacy interests and meaningful interference [with possessions], not to cover all technical trespasses."[16]

During oral argument, Justice Alito stated that people's use of technology is changing what the expectation of privacy is for the courts. "You know, I don't know what society expects and I think it's changing. Technology is changing people's expectations of privacy. Suppose we look forward 10 years, and maybe 10 years from now 90 percent of the population will be using social networking sites and they will have on average 500 friends and they will have allowed their friends to monitor their location 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, through the use of their cell phones. Then — what would the expectation of privacy be then?"[17]

Justice Sonia Sotomayor reminded the government, "What motivated the Fourth Amendment historically was the disapproval, the outrage, that our Founding Fathers experienced with general warrants that permitted police indiscriminately to investigate just on the basis of suspicion, not probable cause, and to invade every possession that the individual had in search of a crime." She then asked, "How is this different?"[18]

Opinion of the Court

On January 23, 2012, the Supreme Court held that "the Government's installation of a GPS device on a target's vehicle, and its use of that device to monitor the vehicle's movements, constitutes a 'search'" under the Fourth Amendment.[19][20][21] Some news sources have misinterpreted the Court as holding that all GPS data surveillance requires a search warrant,[22] but this ruling was much narrower than that

On the one hand, it can be said that all nine justices unanimously considered the police's actions in Jones to be unconstitutional. Importantly, however, although they reached the same result in the end, they were split 5-4, with the two groups in disagreement as to the fundamental reasons for their conclusion. Further, the justices were of three different opinions with respect to the breadth of the judgment.[23]

Majority opinion

Justice Antonin Scalia authored the majority opinion. He cited a line of cases dating back as far as 1886 to argue that a physical intrusion, or trespass, into a constitutionally-protected area – in an attempt to find something or to obtain information – was the basis, historically, for determining whether a "search" had occurred under the meaning of the Fourth Amendment.[24] Scalia conceded that in the years following Katz v. United States (1967) – in which electronic eavesdropping on a public telephone booth was held to be a search – the vast majority of search and seizure case law has shifted away from that approach founded on property rights, and towards an approach based on a person's "expectation of privacy".[25] However, he cited a number of post-Katz cases including Alderman v. United States[26] and Soldal v. Cook County[27] to argue that the trespassory approach had not been abandoned by the Court.[28] In response to criticisms within Alito's concurrence, Scalia emphasized that the Fourth Amendment must provide, at a minimum, the level of protection as it did when it was adopted. Furthermore, a trespassory test need not exclude a test of the expectation of privacy, which may be appropriate to consider in situations where there was no governmental trespass.[29]

In the instant case, the Court concluded, since the Government's installation of a GPS device onto the defendant's car (his "personal effects") was a trespass that was purposed to obtain information, then it was a search under the Fourth Amendment.

Having reached the conclusion that this was a search under the Fourth Amendment, the Court declined to examine whether any exception exists that would render the search "reasonable", because the Government had failed to advance that alternate theory in the lower courts.[30][31] Also left unanswered was the broader question surrounding the privacy implications of a warrantless use of GPS data absent a physical intrusion – as might occur, for example, with the electronic collection of GPS data from wireless service providers or factory-installed vehicle tracking and navigation services.[23] The Court left this to be decided in some future case, saying, "It may be that achieving the same result through electronic means, without an accompanying trespass, is an unconstitutional invasion of privacy, but the present case does not require us to answer that question."[32]

Concurring opinions

Justice Sotomayor

Justice Sonia Sotomayor was alone in her concurring opinion. She was the fifth justice to concur with Scalia's opinion, making hers the decisive vote.[33] "As the majority's opinion makes clear", she noted, "Katz's reasonable-expectation-of-privacy test augmented, but did not displace or diminish, the common-law trespassory test that preceded it".[34] She agreed with Alito's expectation of privacy reasoning with respect to long-term surveillance,[35] but she went a step further, by also disputing the constitutionality of warrantless short-term GPS surveillance as well. Even during short-term monitoring, she reasoned, GPS surveillance can precisely record an individual's every movement, and hence can reveal completely private destinations, like "trips to the psychiatrist, the plastic surgeon, the abortion clinic, the AIDS treatment center, the strip club, the criminal defense attorney, the by-the-hour motel, the union meeting, the mosque, synagogue or church, the gay bar and on and on."[35] Sotomayor added:

"People disclose the phone numbers that they dial or text to their cellular providers, the URLS that they visit and the e-mail addresses with which they correspond to their Internet service providers, and the books, groceries and medications they purchase to online retailers . . . I would not assume that all information voluntarily disclosed to some member of the public for a limited purpose is, for that reason alone, disentitled to Fourth Amendment protection."[36]

She distinguished Knotts, reminding that Knotts suggested that a different principle might apply to situations in which every movement was completely monitored for 24 hours.[37]

Justice Alito

In his concurring opinion, Justice Alito wrote with respect to privacy: "Short-term monitoring of a person’s movements on public streets accords with expectations of privacy" but "the use of longer term GPS monitoring in investigations of most offenses impinges on expectations of privacy."[38] Alito argued against the majority's reliance on trespass under modern circumstances. Specifically, he argued that the common-law property-based analysis of a "search" under the Fourth Amendment did not apply to such electronic situations as the one that occurred in this case.[39] He further argued that following the doctrinal changes in Katz, a technical trespass leading to the gathering of evidence was "neither necessary nor sufficient to establish a constitutional violation".[40][41] In his concurring opinion Alito outlined that long-term surveillance can reveal everything about a person:

"Prolonged surveillance reveals types of information not revealed by short-term surveillance, such as what a person does repeatedly, what he does not do, and what he does ensemble. These types of information can each reveal more about a person than does any individual trip viewed in isolation. Repeated visits to a church, a gym, a bar, or a bookie tell a story not told by any single visit, as does one's not visiting any of these places over the course of a month. The sequence of a person's movements can reveal still more; a single trip to a gynecologist's office tells little about a woman, but that trip followed a few weeks later by a visit to a baby supply store tells a different story.* A person who knows all of another's travels can deduce whether he is a weekly church goer, a heavy drinker, a regular at the gym, an unfaithful husband, an outpatient receiving medical treatment, an associate of particular individuals or political groups – and not just one such fact about a person, but all such facts."[42]

Following the privacy-based approach most commonly used post-Katz, the four-justice minority are instead of the opinion that the continuous monitoring of every single movement of an individual's car for 28 days violated a "reasonable expectation of privacy", and thus constituted a search. Alito explained that before GPS and similar electronic technology, month-long surveillance of an individual's every move would have been exceptionally demanding and costly, requiring a tremendous amount of resources and people. As a result, society's expectations were, and still are, that such complete and long-term surveillance would not be undertaken, and that an individual would not think it could occur to him or her.[43]

With regard to continuous monitoring for a short period, the minority would rely on United States v. Knotts (1983) and decline to find a violation of the expectation of privacy.[43] In Knotts, a short-distance signal beeper in the defendant's car was tracked during a single trip for less than a day. The Knotts Court held that a person traveling on public roads has no expectation of privacy in his movements, because the vehicle's starting point, direction, stops, or final destination could be seen by anyone else on the road.[44]

Reception

Walter E. Dellinger III, the former U.S. Solicitor General and the attorney who represented the defendant, said the decision was "a signal event in Fourth Amendment history."[2] He also said the decision made it more risky for law enforcement to use a GPS tracking device without a warrant.[45] FBI director Robert Mueller testified in March 2013 that the Jones decision had limited the Bureau's surveillance capabilities.[46]

Criminal defense attorneys and civil libertarians such as Virginia Sloan of the Constitution Project praised the ruling for protecting Fourth Amendment rights against government intrusion through modern technology.[45] The Electronic Frontier Foundation, which filed an amicus brief arguing that warrantless GPS tracking violates reasonable expectations of privacy, praised Sotomayor's concurrence for raising concerns that Fourth Amendment caselaw does not reflect the realities of modern technology.[47]

Subsequent developments

The Supreme Court remanded the case to the district court. During the investigation, the government obtained cell site location data with a 2703(d) order under the Stored Communications Act.[9] In light of the Supreme Court's decision, the government sought to use this data instead of the GPS data it had collected. Judge Ellen Segal Huvelle ruled in December 2012 that the government could use the cell site data against Jones.[48] A new trial began in January 2013[49] after Mr Jones rejected 2 plea offers of 15 to 22 years with credit for time served.[50] In March 2013,[51] a mistrial was declared with the jury evenly split. Mr. Jones had represented himself at trial.[52][53] The Government planned for a fourth trial[54][55] but in May 2013 Jones accepted a plea bargain of 15 years with credit for time served.[56][57]

In October 2013, the Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit addressed the unanswered question of "whether warrantless use of GPS devices would be 'reasonable — and thus lawful — under the Fourth Amendment [where] officers ha[ve] reasonable suspicion, and indeed probable cause' to execute such searches."[58] United States v. Katzin was the first relevant appeals court ruling in the wake of Jones to address this topic. The appeals court in Katzin held that a warrant was indeed required to deploy GPS tracking devices, and further, that none of the narrow exceptions to the Fourth Amendment's warrant requirement (e.g. exigent circumstances, the "automobile exception", etc.) were applicable.[59][60]

See also

- Geolocation Privacy and Surveillance Act

- Kyllo v. United States

- United States v. Graham

- Florida v. Jardines

Notes

- ↑ United States v. Maynard, Opinion p. 16 "Jones owned and Maynard managed the "Levels" nightclub in the District of Columbia. In 2004 an FBI Metropolitan Police Department Safe Streets Task Force began investigating the two for narcotics violations."

- 1 2 Bravin, Jess, "Justices Rein In Police on GPS Trackers", The Wall Street Journal, January 24, 2012. Retrieved 2012-01-24.

- ↑ United States v. Maynard, Opinion p. 38, "The police had obtained a warrant to install the GPS device in D.C. only, but it had expired before they installed it — which they did in Maryland."

- ↑ United States v. Maynard, Opinion p. 3, "...tracking [Jones's] movements 24 hours a day for four weeks (sic) with a GPS device [the police] had installed on his Jeep..."

- ↑ United States v. Maynard, Opinion p. 4, " the Government filed another superseding indictment charging Jones, Maynard, and a few co-defendants with a single count of conspiracy to distribute and to possess with intent to distribute five or more kilograms of cocaine and 50 or more grams of cocaine base. A joint trial of Jones and Maynard began in November 2007 and ended in January 2008, when the jury found them both guilty. "

- ↑ United States v. Jones, Petition for a Writ of Certiorari p. 2, "respondent was convicted of conspiracy to distribute five kilograms or more of cocaine and 50 or more grams of cocaine base, in violation of 21 U.S.C. 841 and 846. The district court sentenced respondent to ."

- ↑ United States v. Maynard, Opinion p. 15-16 "Jones argues his conviction should be overturned because the police violated the Fourth Amendment prohibition of unreasonable searches by tracking his movements 24 hours a day for four weeks with a GPS device they had installed on his Jeep without a valid warrant."

- ↑ United States v. Maynard, Opinion p. 16 "As explained below, we hold Knotts does not govern this case and the police action was a search because it defeated Jones‘s reasonable expectation of privacy."

- 1 2 Justin P. Webb, Cybercrime Review (November 29, 2012). "Highlighted Paper: Orin Kerr, The Mosaic Theory of the Fourth Amendment".

- ↑ Justin P. Webb (December 1, 2011). "Carving Out Notions of Privacy: The Impact of GPS Tracking and Why Maynard is a Move in the Right Direction".

- ↑ United States v. Jones, Docket, Certiorari granted (June 27, 2011).

- ↑ United States v. Jones (Oral Argument Transcript) p. 1.

- 1 2 United States v. Jones (Oral Argument Transcript) p. 3.

- ↑ United States v. Jones (Oral Argument Transcript) p. 4.

- ↑ United States v. Jones (Oral Argument Transcript) p. 7.

- ↑ United States v. Jones (Oral Argument Transcript) p. 8.

- ↑ United States v. Jones (Oral Argument Transcript) p. 44.

- ↑ United States v. Jones (Oral Argument Transcript) p. 20.

- ↑ United States v Jones (Opinion) Majority p.3.

- ↑ Romm, Tony (23 July 2012). "Supreme Court: GPS location tracking qualifies as search". POLITICO.com. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ↑ Liptak, Adam (23 January 2013). "Justices Say GPS Tracker Violated Privacy Rights". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- ↑ Bill Mears (January 23, 2012). "Justices rule against police, say GPS surveillance requires search warrant". CNN.

- 1 2 Goldstein, Tom (30 January 2012). "Why Jones is still less of a pro-privacy decision than most thought". SCOTUSblog. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- ↑ United States v Jones (Opinion) Majority pp. 4-5.

- ↑ United States v Jones (Opinion) Majority p. 5.

- ↑ Alderman v. United States, 394 U.S. 165, 180 (1969). "[W]e [do not] believe that Katz, by holding that the Fourth Amendment protects persons and their private conversations, was intended to withdraw any of the protection which the Amendment extends to the home . . . ."

- ↑ Soldal v. Cook County, 506 U.S. 56, 64 (1992). "[Katz established that] property rights are not the sole measure of Fourth Amendment violations. . . . [it did not] snuf[f] out the previously recognized protection for property."

- ↑ United States v Jones (Opinion) Majority pp. 5-7.

- ↑ United States v Jones (Opinion) Majority pp. 10-12.

- ↑ Kravets, David (23 January 2012). "Supreme Court Court Rejects Willy-Nilly GPS Tracking". Wired.com. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ↑ Kerr, Orin (23 January 2012). "What Jones Does Not Hold". The Volokh Conspiracy. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ↑ United States v Jones (Opinion) Majority p. 11.

- ↑ United States v Jones (Opinion) Sotomayor concurrence, p. 1.

- ↑ United States v Jones (Opinion) Sotomayor concurrence, p. 2.

- 1 2 United States v Jones (Opinion) Sotomayor concurrence, p. 3.

- ↑ United States v. Jones, 565 U.S. ___, 132 S. Ct. 945, 957 (2012) (Sotomayor, J., concurring).

- ↑ United States v Jones (Opinion) Sotomayor concurrence, p. 4.

- ↑ United States v. Jones, 565 U.S., 132 S. Ct. 945, 964 (2012) (Alito, J. concurring).

- ↑ United States v Jones (Opinion) Alito concurrence, pp. 2-3.

- ↑ United States v Jones (Opinion) Alito concurrence, p. 6, quoting from United States v. Karo, 468 U.S. 705, 713 (1984).

- ↑ Justice Scalia countered this quote from Karo (that "[trespass is] neither necessary nor sufficient...") by calling it "irrelevant" – Karo contemplated a seizure, not a search, and trespass has no bearing on the constitutionality of a seizure. United States v Jones (Opinion) Majority p. 7, note 5.

- ↑ U.S. v. Maynard, 615 F.3d 544 (U.S., D.C. Circ., C.A.)p. 562; U.S. v. Jones, 565 U.S. __, (2012), Alito, J., concurring.

- 1 2 United States v Jones (Opinion) Alito's concurrence, p. 13.

- ↑ United States v. Knotts, 460 U.S. 276, 282 (1983).

- 1 2 Biskupic, Joan (January 24, 2012). "Supreme Court rules warrant needed for GPS tracking". USA Today. Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- ↑ Johnson, Carrie (March 21, 2012). "FBI Still Struggling With Supreme Court's GPS Ruling". NPR. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ↑ "US v. Jones". Electronic Frontier Foundation. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ↑ Mike Scarcella (17 December 2012). "Judge Rules for DOJ in Dispute Over Cell Tower Data". Legal Times Blog.

- ↑ Zapotosky, Matt (25 January 2013). "Accused drug dealer, representing himself, hears prosecutors open their case". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Marimow, Ann (16 January 2013). "Suspected D.C. drug kingpin offered plea deal". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Frommer, Frederic (4 March 2013). "Mistrial declared in 3rd trial of drug conspiracy". US News & World Report. Associated Press.

- ↑ Marimow, Ann (17 January 2013). "Suspected D.C. drug kingpin to represent himself at retrial". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Zapotosky, Matt (28 January 2013). "Accused D.C. dealer launches his own defense at trial". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Marimow, Ann (5 March 2013). "Judge declares mistrial in area drug case". The Washington Post. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ↑ "Judge Declares Mistrial in Drug Case at Center of Landmark Supreme Court Ruling". Legal Times Blog. 4 March 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ↑ "Antoine Jones pleads guilty, accepts 15 years sentence". WJLA-TV. 1 May 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ↑ Anderson, Nick (1 May 2013). "Former DC Nightclub owner Antoine Jones sentenced on drug charge.". The Washington Post. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ↑ United States v. Katzin, 12-2548 (3d Cir. 2013). , quoting United States v Jones (Opinion) Majority p. 5.

- ↑ Zetter, Kim (October 22, 2013). "Court Rules Probable-Cause Warrant Required for GPS Trackers". Wired.com. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- ↑ Kemp, David S. "The Warrant Requirement for GPS Tracking Devices". Verdict. Justia. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

References

- United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia (August 2010). "United States v. Maynard (Opinion)" (PDF).

- Department of Justice (2010). "United States v. Jones (Petition for Writ of Certiorari)" (PDF).

- Supreme Court of the United States (April 2011). "United States v. Jones (Docket)".

- Supreme Court of the United States (June 2011). "United States v. Jones (Questions Presented)" (PDF).

- Supreme Court of the United States (November 2011). "United States v. Jones (Oral Argument Transcript)" (PDF).

- Supreme Court of the United States (January 2012). "United States v. Jones (Opinions)" (PDF).

Further reading

- Arcila, Fabio, Jr. (2012). "GPS Tracking Out of Fourth Amendment Dead Ends: United States v. Jones and the Katz Conundrum". North Carolina Law Review 91 (1): 1–59.

- United States v. Jones: GPS Monitoring, Property, and Privacy Congressional Research Service

External links

- Text of United States v. Jones, 565 U.S. ___ (2012), Docket 10-1259 is available from: Findlaw Justia Google Scholar U.S. Supreme Court