United Kingdom general election, 1997

| | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Colours denote the winning party, as shown in the main table of results. * Indicates boundary change – so this is a nominal figure ^ Figure does not include the speaker | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1987 election • MPs |

| 1992 election • MPs |

| 1997 election • MPs |

| 2001 election • MPs |

| 2005 election • MPs |

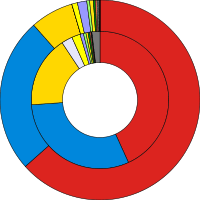

The United Kingdom general election of 1997 was held on 1 May 1997, five years after the previous election on 9 April 1992, to elect 659 members to the British House of Commons. Under the leadership of Tony Blair, the Labour Party ended its 18 years in opposition and won the general election with a landslide victory, winning 418 seats, the most seats the party has ever held. The election saw a huge 10.2% swing from the Conservatives to Labour. Blair, as a result, became Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, a position he held until his resignation in 2007.

Under Blair's leadership, the Labour Party had adopted a more centrist policy platform under the name 'New Labour'. This was seen as moving away from the traditionally more left-wing stance of the Labour Party. Labour made several campaign pledges such as the creation of a National Minimum Wage, devolution referendums for Scotland and Wales and promised greater economic competence than the Conservatives, who were unpopular following the events of Black Wednesday in 1992. The Labour campaign was ultimately a success and the party returned an unprecedented 418 MPs and began the first of three consecutive terms for Labour in government. However, 1997 remains the last election in which Labour had a net gain of seats. A record number of women were elected to parliament, 120, of whom 101 were Labour MPs. This was in part thanks to Labour's policy of using all-women shortlists.

The Conservative Party was led by incumbent Prime Minister John Major and ran their campaign emphasising falling unemployment and a strong economic recovery following the early 1990s recession. However, a series of scandals, party disunity over the European Union, the events of Black Wednesday and a desire of the electorate for change after 18 years of Tory rule all contributed to the Conservatives' worst defeat since 1906, with only 165 MPs elected to Westminster, as well as their lowest percentage share of the vote since 1832. The party was left with no seats whatsoever in Scotland or Wales, and many key Conservative politicians, including Defence Secretary Michael Portillo, Foreign Secretary Malcolm Rifkind, Trade Secretary Ian Lang, Scottish Secretary Michael Forsyth and former ministers Edwina Currie, Norman Lamont, David Mellor and Neil Hamilton all lost their parliamentary seats. Following the defeat, the Conservatives began the longest continuous spell in opposition in the history of the present day (post-Tamworth Manifesto) Conservative Party, and indeed the longest such spell for any incarnation of the Tories/Conservatives since the 1760s, lasting 13 years.

The Liberal Democrats, under Paddy Ashdown, returned 46 MPs to parliament, the most for any third party since 1929 and more than double the seats they got in 1992, despite a drop in popular vote. The Scottish National Party (SNP) returned 6 MPs, double their total in 1992.

As with all general elections since the early 1950s, the results were broadcast live on the BBC; the presenters were David Dimbleby, Peter Snow and Jeremy Paxman.[1]

Overview

The British economy had been in recession at the time of the 1992 election, which the Conservatives had won, and although the recession had ended within a year, events such as Black Wednesday had tarnished the Conservative government's reputation for economic management. Labour had elected John Smith as its party leader in 1992, however his death from heart attack in 1994 led the way for Tony Blair to become Labour leader. Blair brought the party closer to the political centre and abolished the party's Clause IV in their constitution, which had committed them to mass nationalisation of industry. Labour also reversed its policy on unilateral nuclear disarmament and the events of Black Wednesday allowed Labour to promise greater economic management under the Chancellorship of Gordon Brown. A manifesto, entitled New Labour, New Life For Britain was released in 1996 and outlined 5 key pledges:

- Class sizes to be cut to 30 or under for 5, 6 and 7 year-olds by using money from the assisted places scheme.

- Fast-track punishment for persistent young offenders by halving the time from arrest to sentencing.

- Cut NHS waiting lists by treating an extra 100,000 patients as a first step by releasing £100 million saved from NHS red tape.

- Get 250,000 under-25-year-olds off benefit and into work by using money from a windfall levy on the privatised utilities.

- No rise in income tax rates, cut VAT on heating to 5 per cent, and keeping inflation and interest rates as low as possible.

Disputes within the Conservative government over European Union issues, and a variety of "sleaze" allegations had severely affected the government's popularity. Despite the strong economic recovery and substantial fall in unemployment in the four years leading up to the election, the rise in Conservative support was only marginal with all of the major opinion polls having shown Labour in a comfortable lead since late 1992.[2]

Timing

The previous Parliament first sat on 29 April 1992. The Parliament Act 1911 required at the time for each Parliament to be dissolved before the 5th anniversary of its first sitting, therefore the latest date the dissolution and the summoning of the next parliament could have been held on was 28 April 1997. The 1985 amendment of the Representation of the People Act 1983 required that the election must take place on the 11th working day after the deadline for nomination papers, which in turn must be no more than six working days after the next parliament was summoned. Therefore, the latest date the election could have been held on was 22 May 1997 (which happened to be a Thursday). British elections (and referenda) have been held on Thursdays by convention since the 1930s, but can be held on other working days.

Campaign

Prime Minister John Major called the election on Monday 17 March 1997, ensuring the formal campaign would be unusually long, at six weeks (Parliament was dissolved on 8 April[3]). The election was scheduled for 1 May, to coincide with the local elections on the same day. This set a precedent, as the three subsequent general elections have also been held alongside the May local elections. The Conservatives argued that a long campaign would expose Labour and allow the Conservative message to be heard. However, Major was accused of arranging an early dissolution to protect Neil Hamilton from a pending parliamentary report into his conduct: a report that Major had earlier guaranteed would be published before the election.

Conservative campaign

The Conservatives started low in the polls, and had experienced great difficulties over the past 5 years, with polling often putting it some 40 points adrift of Labour. Major hoped that a long campaign would expose Labour's "hollowness" and the Conservative campaign emphasised stability, as did its manifesto title 'You can only be sure with the Conservatives'.[4] However, the campaign was beset by deep set problems, such as the rise of James Goldsmith's Referendum Party, advocating a referendum on continued membership of the European Union. The Party threatened to take away many right-leaning voters from the Conservatives. Furthermore, about 200 candidates broke with official Conservative policy to oppose British membership of the single European currency.[5] Major fought back, saying: "Whether you agree with me or disagree with me; like me or loathe me, don't bind my hands when I am negotiating on behalf of the British nation." The moment is remembered as one of the defining, and most surreal, moments of the election.[6][4]

Meanwhile, there was also division amongst the Conservative cabinet, with Chancellor Ken Clarke describing the views of Home Secretary Michael Howard on Europe as "paranoid and xenophobic nonsense". The Conservatives also struggled to come up with a definitive theme to attack the Labour Party, with some strategists arguing for an approach which castigated Labour for "stealing Tory clothes" (copying their positions), with others making the case for a more confrontational approach, stating that "New Labour" was just a façade for "old Labour". The New Labour, New Danger poster, which depicted Tony Blair with demon eyes, was an example of the latter strategy. Major veered between the two approaches, which left Conservative Central Office staff frustrated. As Andrew Cooper explained: "We repeatedly tried and failed to get him to understand that you couldn't say that they were dangerous and copying you at the same time."[7] In any case, the campaign failed to gain much traction, and the Conservatives went down to a landslide defeat at the polls.

Labour campaign

Labour ran a slick campaign, which emphasised the splits within the Conservative government, and argued that the country needed a more centrist administration. Labour ran a centrist campaign that was good at picking up dissatisfied Tory voters, particularly moderate and suburban ones. Tony Blair, highly popular, was very much the centrepiece of the campaign, and proved a highly effective campaigner. The Labour campaign was reminiscent of those of Bill Clinton for the US Presidency, focusing on centrist themes, as well as adopting policies more commonly associated with the right, such as cracking down on crime and fiscal responsibility.

Liberal Democrat campaign

The Liberal Democrats had suffered a disappointing performance in 1992, but they were very much strengthened in 1997 due to potential tactical voting between Labour and Lib Dem supporters in Tory marginal constituencies, particularly in the south - particularly given their share of the vote decreased whilst their number of seats nearly doubled. The Lib Dems promised to increase education funding.

Notional 1992 election

The election was fought under new boundaries, with a net increase of eight seats compared to the 1992 election (651 to 659). Changes listed here are from the notional 1992 result, had it been fought on the boundaries established in 1997. These notional results were calculated by Colin Rallings and Michael Thrasher and were used by all media organisations at the time.

| UK General Election 1992 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Seats | Gains | Losses | Net gain/loss | Seats % | Votes % | Votes | +/− | ||

| Labour | 273 | 17 | 15 | +2 | 41.6 | 34.4 | 11,560,484 | |||

| Conservative | 343 | 28 | 21 | +7 | 52.1 | 41.9 | 14,093,007 | |||

| Liberal Democrat | 18 | 0 | 2 | −2 | 2.7 | 17.8 | 5,999,384 | |||

| Others | 25 | 1 | 0 | +1 | 3.6 | 5.9 | ||||

Results

Labour won a landslide victory with their largest parliamentary majority (179) to date. On the BBC's election night programme Professor Anthony King described the result of the exit poll, which accurately predicted a Labour landslide, as being akin to "an asteroid hitting the planet and destroying practically all life on Earth". After years of trying the Labour Party had convinced the electorate that they would usher in a new age of prosperity—their policies, organisation and tone of optimism slotting perfectly into place.

Labour's victory was largely credited to the charisma of Tony Blair and a Labour public relations machine managed by Alastair Campbell. Between the 1992 election and the 1997 election there had also been major steps to modernise the party, including scrapping Clause IV that had committed the party to extending public ownership of industry. New Labour had suddenly seized the middle ground of the political spectrum, attracting voters much further to the right than their traditional working class or left-wing support. Famously, in the early hours of 2 May 1997 a party was held at the Royal Festival Hall, in which Blair stated triumphantly that "a new dawn has broken, has it not?".

The election was a crushing defeat for the Conservative Party, with the party having its lowest percentage share of the popular vote since 1832 under the Duke of Wellington's leadership, being wiped out in Scotland and Wales. A number of prominent Conservative MPs lost their seats in the election, including Michael Portillo, Malcolm Rifkind, Edwina Currie, David Mellor, Neil Hamilton and Norman Lamont. Such was the extent of Conservative losses at the election that Cecil Parkinson, speaking on the BBC's election night programme, remarked upon the Conservatives winning their second seat that he was pleased that the subsequent election for the leadership would be contested.

The election was a massive success for the Liberal Democrats, who more than doubled their number of seats thanks to the use of tactical voting against the Conservatives. Although their share of the vote fell slightly, their total of 46 MPs was the highest since Lloyd George got 59 seats in 1929.

The Referendum Party, which sought a referendum on the United Kingdom's relationship with the European Union, came fourth in terms of votes with 800,000 votes mainly from former Conservative voters, but won no seats in parliament. The six parties with the next highest votes stood only in either Scotland, Northern Ireland or Wales; in order, they were the Scottish National Party, the Ulster Unionist Party, the Social Democratic and Labour Party, Plaid Cymru, Sinn Féin, and the Democratic Unionist Party.

In the previously safe seat of Tatton, where incumbent Conservative MP Neil Hamilton was facing charges of having taken cash for questions, the Labour and Liberal Democrat Parties decided not to field candidates in order that an Independent candidate, Martin Bell, would have a better chance of winning the seat, which he duly did with a comfortable margin.

The result declared for the constituency of Winchester showed a margin of victory of just two votes for the Liberal Democrats. The defeated Conservative candidate mounted a successful legal challenge to the result on the grounds that errors by election officials (failures to stamp certain votes) had changed the result, the court ruled the result invalid and ordered a by-election on 20 November which was won by the Liberal Democrats with a much larger majority, causing much recrimination in the Conservative Party about the decision to challenge the original result in the first place.

This election would also mark the start of Labour government for the next 13 years until the formation of the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition in 2010.

| 418 | 165 | 46 | 30 |

| Labour | Conservative | Lib Dem | O |

| UK General Election 1997 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candidates | Votes | ||||||||||

| Party | Leader | Standing | Elected | Gained | Unseated | Net | % of total | % | No. | Net % | |

| Labour | Tony Blair | 639 | 418 | 145 | 0 | + 145 | 63.4 | 43.2 | 13,518,167 | +8.8 | |

| Conservative | John Major | 648 | 165 | 0 | 178 | –178 | 25.0 | 30.7 | 9,600,943 | –11.2 | |

| Liberal Democrat | Paddy Ashdown | 639 | 46 | 30 | 2 | + 28 | 7.0 | 16.8 | 5,242,947 | –1.0 | |

| Referendum | James Goldsmith | 547 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.6 | 811,849 | N/A | ||

| SNP | Alex Salmond | 72 | 6 | 3 | 0 | + 3 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 621,550 | +0.1 | |

| UUP | David Trimble | 16 | 10 | 1 | 0 | +1 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 258,349 | 0.0 | |

| SDLP | John Hume | 18 | 3 | 0 | 1 | –1 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 190,814 | +0.1 | |

| Plaid Cymru | Dafydd Wigley | 40 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 161,030 | 0.0 | |

| Sinn Féin | Gerry Adams | 17 | 2 | 2 | 0 | + 2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 126,921 | 0.0 | |

| DUP | Ian Paisley | 9 | 2 | 0 | 1 | –1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 107,348 | 0.0 | |

| UKIP | Alan Sked | 193 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 105,722 | N/A | ||

| Independent | N/A | 25 | 1 | 1 | 0 | +1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 64,482 | 0.0 | |

| Green | Peg Alexander and David Taylor | 89 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 61,731 | –0.2 | ||

| Alliance | John Alderdice | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 62,972 | 0.0 | ||

| Socialist Labour | Arthur Scargill | 64 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 52,109 | N/A | ||

| Liberal | Michael Meadowcroft | 53 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 45,166 | –0.1 | ||

| BNP | John Tyndall | 57 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 35,832 | 0.0 | ||

| Natural Law | Geoffrey Clements | 197 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 30,604 | –0.1 | ||

| Speaker | Betty Boothroyd | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 23,969 | |||

| ProLife Alliance | Bruno Quintavalle | 56 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 19,332 | N/A | ||

| UK Unionist | Robert McCartney | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | +1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 12,817 | N/A | |

| PUP | Hugh Smyth | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 10,928 | N/A | ||

| National Democrats | Ian Anderson | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 10,829 | N/A | ||

| Socialist Alternative | Peter Taaffe | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 9,906 | N/A | |||

| Scottish Socialist | Tommy Sheridan | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 9,740 | N/A | ||

| Independent Labour | N/A | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 9,233 | – 0.1 | ||

| Independent Conservative | N/A | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 8,608 | –0.1 | ||

| Monster Raving Loony | Screaming Lord Sutch | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 7,906 | –0.1 | ||

| Rainbow Dream Ticket | Rainbow George Weiss | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3,745 | N/A | ||

| NI Women's Coalition | Monica McWilliams and Pearl Sagar | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3,024 | N/A | ||

| Workers' Party | Tom French | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2,766 | –0.1 | ||

| National Front | John McAuley | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2,716 | N/A | ||

| Legalise Cannabis | Howard Marks | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2,085 | N/A | ||

| People's Labour | Jim Hamezian | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,995 | N/A | ||

| Mebyon Kernow | Loveday Jenkin | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,906 | N/A | ||

| Scottish Green | Robin Harper | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,721 | |||

| Conservative Anti-Euro | Christopher Story | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,434 | N/A | ||

| Socialist (GB) | None | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,359 | N/A | |||

| Community Representative | Ralph Knight | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,290 | N/A | ||

| Residents | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,263 | N/A | |||

| Social Democratic | John Bates | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,246 | –0.1 | ||

| Workers Revolutionary | Sheila Torrance | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,178 | N/A | ||

| Real Labour | N/A | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,117 | N/A | ||

| Independent Democratic | N/A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 982 | ||||

| Independent Liberal Democrat | N/A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 890 | ||||

| Communist | Mike Hicks | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 639 | |||

| Independent Green | N/A | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 593 | |||

| Green (NI) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 539 | ||||

| Socialist Equality | Davy Hyland | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 505 | |||

All parties with more than 500 votes shown. Labour total includes New Labour and "Labour Time for Change" candidates; Conservative total includes candidates in Northern Ireland (excluded in some lists) and "Loyal Conservative" candidate.

The Popular Unionist MP elected in 1992 died in 1995 and the party folded shortly afterwards.

There was no incumbent Speaker in the 1992 election.

| Government's new majority | 179 |

| Total votes cast | 31,286,284 |

| Turnout | 71.3% |

Defeated Conservatives

Ministers who lost their seats

- Tony Newton (Braintree) - Lord President of the Council and Leader of the House of Commons

- Michael Portillo (Enfield Southgate) - Secretary of State for Defence

- Malcolm Rifkind (Edinburgh Pentlands) - Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs

- Ian Lang (Galloway and Upper Nithsdale) - Secretary of State for Trade and Industry

- Michael Forsyth (Stirling) - Secretary of State for Scotland

- William Waldegrave (Bristol West) - Chief Secretary to the Treasury

- Roger Freeman (Kettering) - Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

- Sir Derek Spencer (Brighton Pavilion) - Solicitor General for England and Wales

- Michael Morris (Northampton South) - Chairman of Ways and Means

- Alistair Burt (Bury North) - Minister of State at Department of Social Security

- Phillip Oppenheim (Amber Valley) - Exchequer Secretary to the Treasury

- Michael Bates (Langbaurgh) - Paymaster-General

- Raymond Robertson (Aberdeen South) - Minister for Education, Housing, Fisheries and Sport

- Greg Knight (Derby North) - Minister of State for Industry at the Department of Trade and Industry

- John Bowis OBE (Battersea) - Health Minister

- Iain Sproat (Harwich) - Trade Minister

- Robin Squire (Hornchurch) - Education Minister

- Andrew Mitchell (Gedling) - Social Security Minister

- The Hon. Tom Sackville (Bolton, West) - Home Office Minister

- Sir Nicholas Bonsor, 4th Baronet (Upminster) - Foreign Office Minister

- Timothy Kirkhope (Leeds North West) - Under-Secretary of State for the Home Department

- Gwilym Jones (Cardiff North) - Under Secretary of State in the Welsh Office

- George Kynoch (Kincardine and Deeside) - Under-Secretary of State for Scotland

- Roger Evans (Monmouth) - Social Security Minister

- David Evennett (Erith and Crayford) - Parliamentary Private Secretary to the Secretary of State for Education and Skills

- Lady Olga Maitland (Sutton and Cheam) - Parliamentary Private Secretary to The Rt. Hon. Sir John Wheeler

- Simon Coombs (Swindon) - Parliamentary Private Secretary to The Rt. Hon. Ian Lang

- Timothy Wood (Stevenage) - Comptroller of the Household

- Gyles Brandreth (City of Chester) - Whip

Conservative MPs who lost their seats

Constituencies given are those contested in 1997, rather than those held prior to the election - Norman Lamont, for example, had previously represented Kingston upon Thames in London.

- Dame Angela Rumbold (Mitcham and Morden) - Deputy Chairman of the Conservative Party

- Sir Graham Bright (Luton South) - Vice-Chairman of the Conservative Party

- Sir Marcus Fox (Shipley) - Chairman of the 1922 committee

- Neil Hamilton (Tatton) - Chairman of the Monday Club

- Norman Lamont (Harrogate and Knaresborough) - former Chancellor of the Exchequer

- David Hunt (Wirral West) - former Secretary of State for Wales

- Edwina Currie (South Derbyshire) - former Health Minister

- Richard Tracey (Surbiton) - former Sports Minister

- Sebastian Coe (Falmouth and Camborne) - Olympic gold medalist

- David Mellor (Putney) - former Secretary of State for National Heritage

- John Cope (Northavon) - former Paymaster General

- Sir Robert Atkins (South Ribble) - former Minister for Sport

- Sir Jeremy Hanley (Richmond and Barnes) - former Chairman of the Conservative Party

- Derek Conway (Shrewsbury and Atcham) - former Vice Chamberlain of HM Household

- Sir Rhodes Boyson (Brent North)

- Sir Jim Lester (Broxtowe)

- Sir Ivan Lawrence (Burton)

- Sir Donald Thompson (Calder Valley)

- Sir Malcolm Thornton (Crosby)

- Sir Roger Moate (Faversham)

- Sir John Michael Gorst (Hendon North)

- Sir Kenneth Carlisle (Lincoln)

- Sir Andrew Bowden (Brighton Kemptown)

- Dame Peggy Fenner DBE (Medway)

- Sir Mark Lennox-Boyd (Morecambe and Lunesdale)

- Sir Michael Neubert (Romford)

- Sir James Hill (Southampton Test)

- Sir Dudley Smith (Warwick and Leamington)

- Sir Peter Fry (Wellingborough)

- Nicholas Budgen (Wolverhampton South West)

- Phil Gallie (Ayr)

- Elizabeth Peacock (Batley and Spen)

- Andrew Hargreaves (Birmingham Hall Green)

- Harold Elletson (Blackpool North)

- Jonathan Evans (Brecon and Radnorshire)

- Nirj Deva (Brentford and Isleworth)

- Michael Brown (Brigg and Cleethorpes)

- Michael Stern (Bristol North West)

- David Sumberg (Bury South)

- Nigel Forman (Carshalton and Wallington)

- Den Dover (Chorley)

- Rod Richards (North West Clwyd)

- Graham Riddick (Colne Valley)

- William Powell (Corby)

- David Congdon (Croydon North East)

- Bob Dunn (Dartford)

- David Shaw (Dover)

- Harry Greenway (Ealing North)

- Dr Ian Twinn (Edmonton)

- Spencer Batiste (Elmet)

- Hartley Booth (Finchley)

- Matthew Carrington (Fulham)

- James Couchman (Gillingham)

- Douglas French (Gloucester)

- Paul Marland (West Gloucestershire)

- Jacques Arnold (Gravesham)

- Michael Carttiss (Great Yarmouth)

- Warren Hawksley (Halesowen and Stourbridge)

- Jerry Hayes (Harlow)

- Hugh Dykes (Harrow East)

- Robert Gurth Hughes (Harrow West)

- John Leslie Marshall (Hendon South)

- Sir Colin Shepherd (Hereford)

- Robert Jones (West Hertfordshire)

- Charles Hendry (High Peak)

- Vivian Bendall (Ilford North)

- Gary Waller (Keighley)

- Dr Keith Hampson (Leeds North West)

- David Ashby (North West Leicestershire)

- Tim Rathbone (Lewes)

- Barry Legg (Milton Keynes South West)

- Peter Butler (North East Milton Keynes)

- Richard Alexander (Newark)

- Henry Bellingham (North West Norfolk)

- Peter Griffiths (Portsmouth North)

- David Martin (Portsmouth South)

- Jim Pawsey (Rugby and Kenilworth)

- John Sykes (Scarborough)

- Michael Stephen (Shoreham)

- John Arthur Watts (Slough)

- Mark Robinson (Somerton and Frome)

- Matthew Banks (Southport)

- Tim Devlin (Stockton South)

- Roger Knapman (Stroud)

- David Nicholson (Taunton)

- Bill Walker (North Tayside)

- Rupert Allason (Torbay)

- Toby Jessel (Twickenham)

- Walter Sweeney (Vale of Glamorgan)

- David Porter (Waveney)

- David Evans (Welwyn Hatfield)

- Charles Goodson-Wickes (Wimbledon)

- Gerry Malone (Winchester)

Liberal Democrats who lost their seats

Referendum Party MP who lost his seat

Post election events

The poor results for the Conservative Party led to infighting, with the One Nation, Tory Reform Group, and right wing Maastricht rebels blaming each other for the defeat. Party chairman Brian Mawhinney said on the night of the election, that it was due to disillusionment with 18 years of Conservative rule. John Major resigned as party leader, saying "When the curtain falls, it is time to leave the stage".

Despite receiving fewer votes than in 1992, the Liberal Democrats more than doubled their number of seats and won their best general election result since 1929 under David Lloyd George's leadership. Paddy Ashdown's continued leadership had been vindicated, despite a disappointing 1992 election, and they were in a position to build positively as a strong third party into the new millennium.

Internet coverage

With the huge rise in internet use since the previous general election, BBC News created a special website covering the election as an experiment for the efficiency of an online news service which was due for a launch later in the year.[8]

See also

- MPs elected in the United Kingdom general election, 1997

- Opinion polling for the United Kingdom general election, 1997

References

- ↑ “”. "BBC Vote '97 Election coverage". YouTube. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ↑ "1997: Labour landslide ends Tory rule". BBC News. 15 April 2005. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ↑ "House of Lords Debates 17 March 1997 vol 579 cc653-4: Dissolution of Parliament". House of Lords Hansard. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- 1 2 Snowdon 2010, p. 4.

- ↑ Travis, Alan (17 April 1997). "Rebels' seven-year march". The Guardian (London).

- ↑ Bevins, Anthony (17 April 1997). "Election '97 : John Major takes on the Tories". The Independent. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ↑ Snowdon 2010, p. 35.

- ↑ "Major events influenced BBC's news online | Social media agency London | FreshNetworks blog". Freshnetworks.com. 5 June 2008. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

Further reading

- Butler, David and Dennis Kavanagh. The British General Election of 1997 (1997), the standard scholarly study

- Snowdon, Peter (2010) [2010]. Back from the Brink: The Extraordinary Fall and Rise of the Conservative Party. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-730884-2.

Manifestos

- Labour (New Labour, New Life For Britain)

- Conservative (You can only be sure with the Conservatives)

- Liberal Democrats (Make the Difference)

- National Democrats (A Manifesto for Britain)

- British National Party (British Nationalism- An Idea whose time has come)

- Liberal Party (Radical ideas – not the dead centre)

- UK Independence Party

- Third Way

- The ProLife Alliance

- Sinn Féin (A New Opportunity for Peace)

- Democratic Unionist Party

- Alliance of Liberty (Agenda for Change)

- Progressive Unionist Party

- Ulster Unionist Party

- Plaid Cymru (The Best for Wales)

- Scottish National Party (Yes We Can Win the Best for Scotland)

- Scottish Green Party

- Socialist Equality Party (A strategy for a workers' government!)

- Communist Party of Great Britain

External links

- BBC Election Website

- Complete BBC coverage of the election night, uploaded on YouTube in 48 parts

- Video of Conservative Michael Portillo losing his seat to Labour's Stephen Twigg

- 1997 election manifestos – Link to 1997 election manifestos of various parties.

- Catalogue of 1997 general election ephemera at the Archives Division of the London School of Economics.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)