Crystal structure

In mineralogy and crystallography, a crystal structure is a unique arrangement of atoms, ions or molecules in a crystalline liquid or solid.[3] It describes a highly ordered structure, occurring due to the intrinsic nature of its constituents to form symmetric patterns.

The box can be thought of as an array of 'small boxes' infinitely repeating in all three spatial directions. Such a unit cell is the smallest unit of volume that contains all of the structural and symmetry information to build-up the macroscopic structure of the lattice by translation.

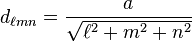

Patterns are located upon the points of a lattice, which is an array of points repeating periodically in three dimensions. The lengths of the edges of a unit cell and the angles between them are called the lattice parameters. The symmetry properties of the crystal are embodied in its space group.[3]

A crystal's structure and symmetry play a role in determining many of its physical properties, such as cleavage, electronic band structure, and optical transparency.

Unit cell

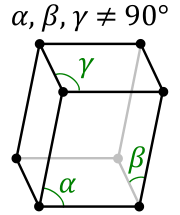

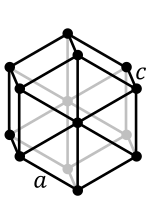

The crystal structure of a material (the arrangement of atoms within a given type of crystal) can be described in terms of its unit cell. The unit cell is a small box containing one or more atoms arranged in 3-dimensions. The unit cells stacked in three-dimensional space describe the bulk arrangement of atoms of the crystal. The unit cell is represented in terms of its lattice parameters, which are the lengths of the cell edges (a,b and c) and the angles between them (alpha, beta and gamma), while the positions of the atoms inside the unit cell are described by the set of atomic positions (xi , yi , zi) measured from a lattice point. Commonly, atomic positions are represented in terms of fractional coordinates, relative to the unit cell lengths.

-

Simple cubic (P)

-

Body-centered cubic (I)

-

Face-centered cubic (F)

The atom positions within the unit cell can be calculated through application of symmetry operations to the asymmetric unit. The asymmetric unit refers to the smallest possible occupation of space within the unit cell. This does not, however imply that the entirety of the asymmetric unit must lie within the boundaries of the unit cell. Symmetric transformations of atom positions are calculated from the space group of the crystal structure, and this is usually a black box operation performed by computer programs. However, manual calculation of the atomic positions within the unit cell can be performed from the asymmetric unit, through the application of the symmetry operators described within the International Tables for Crystallography: Volume A.[4]

Miller indices

Vectors and atomic planes in a crystal lattice can be described by a three-value Miller index notation (ℓmn). The ℓ, m, and n directional indices are separated by 90°, and are thus orthogonal.[5]

By definition, (ℓmn) denotes a plane that intercepts the three points a1/ℓ, a2/m, and a3/n, or some multiple thereof. That is, the Miller indices are proportional to the inverses of the intercepts of the plane with the unit cell (in the basis of the lattice vectors). If one or more of the indices is zero, it means that the planes do not intersect that axis (i.e., the intercept is "at infinity"). A plane containing a co-ordinate axis is translated so that it no longer contains that axis before its Miller indices are determined. The Miller indices for a plane are integers with no common factors. Negative indices are indicated with horizontal bars, as in (123). In an orthogonal co-ordinate system for a cubic cell, the Miller indices of a plane are the Cartesian components of a vector normal to the plane.

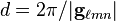

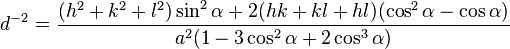

Considering only (ℓmn) planes intersecting one or more lattice points (the lattice planes), the distance d between adjacent lattice planes is related to the (shortest) reciprocal lattice vector orthogonal to the planes by the formula:

Planes and directions

The crystallographic directions are geometric lines linking nodes (atoms, ions or molecules) of a crystal. Likewise, the crystallographic planes are geometric planes linking nodes. Some directions and planes have a higher density of nodes. These high density planes have an influence on the behavior of the crystal as follows:[3]

- Optical properties: Refractive index is directly related to density (or periodic density fluctuations).

- Adsorption and reactivity: Physical adsorption and chemical reactions occur at or near surface atoms or molecules. These phenomena are thus sensitive to the density of nodes.

- Surface tension: The condensation of a material means that the atoms, ions or molecules are more stable if they are surrounded by other similar species. The surface tension of an interface thus varies according to the density on the surface.

- Microstructural defects: Pores and crystallites tend to have straight grain boundaries following higher density planes.

- Cleavage: This typically occurs preferentially parallel to higher density planes.

- Plastic deformation: Dislocation glide occurs preferentially parallel to higher density planes. The perturbation carried by the dislocation (Burgers vector) is along a dense direction. The shift of one node in a more dense direction requires a lesser distortion of the crystal lattice.

Some directions and planes are defined by symmetry of the crystal system. In monoclinic, rombohedral, tetragonal, and trigonal/hexagonal systems there is one unique axis (sometimes called the principal axis) which has higher rotational symmetry than the other two axes. The basal plane is the plane perpendicular to the principal axis in these crystal systems. For triclinic, orthorhombic, and cubic crystal systems the axis designation is arbitrary and there is no principal axis.

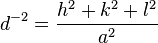

Cubic structures

For the special case of simple cubic crystals, the lattice vectors are orthogonal and of equal length (usually denoted a); similarly for the reciprocal lattice. So, in this common case, the Miller indices (ℓmn) and [ℓmn] both simply denote normals/directions in Cartesian coordinates. For cubic crystals with lattice constant a, the spacing d between adjacent (ℓmn) lattice planes is (from above):

Because of the symmetry of cubic crystals, it is possible to change the place and sign of the integers and have equivalent directions and planes:

- Coordinates in angle brackets such as <100> denote a family of directions that are equivalent due to symmetry operations, such as [100], [010], [001] or the negative of any of those directions.

- Coordinates in curly brackets or braces such as {100} denote a family of plane normals that are equivalent due to symmetry operations, much the way angle brackets denote a family of directions.

For face-centered cubic (fcc) and body-centered cubic (bcc) lattices, the primitive lattice vectors are not orthogonal. However, in these cases the Miller indices are conventionally defined relative to the lattice vectors of the cubic supercell and hence are again simply the Cartesian directions.

Classification

The defining property of a crystal is its inherent symmetry, by which we mean that under certain 'operations' the crystal remains unchanged. All crystals have translational symmetry in three directions, but some have other symmetry elements as well. For example, rotating the crystal 180° about a certain axis may result in an atomic configuration that is identical to the original configuration. The crystal is then said to have a twofold rotational symmetry about this axis. In addition to rotational symmetries like this, a crystal may have symmetries in the form of mirror planes and translational symmetries, and also the so-called "compound symmetries," which are a combination of translation and rotation/mirror symmetries. A full classification of a crystal is achieved when all of these inherent symmetries of the crystal are identified.[6]

Lattice systems

These lattice systems are a grouping of crystal structures according to the axial system used to describe their lattice. Each lattice system consists of a set of three axes in a particular geometric arrangement. There are seven lattice systems. They are similar to but not quite the same as the seven crystal systems and the six crystal families.

| The 7 lattice systems (From least to most symmetric) |

The 14 Bravais Lattices | |||

| 1. triclinic (none) |

| |||

| 2. monoclinic (1 diad) |

simple | base-centered | ||

|

| |||

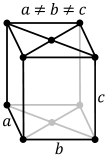

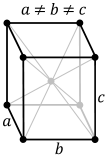

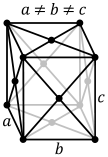

| 3. orthorhombic (3 perpendicular diads) |

simple | base-centered | body-centered | face-centered |

|

|

|

| |

| 4. rhombohedral (1 triad) |

| |||

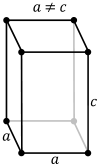

| 5. tetragonal (1 tetrad) |

simple | body-centered | ||

|

| |||

| 6. hexagonal (1 hexad) |

| |||

| 7. cubic (4 triads) |

simple (SC) | body-centered (bcc) | face-centered (fcc) | |

|

|

| ||

The simplest and most symmetric, the cubic (or isometric) system, has the symmetry of a cube, that is, it exhibits four threefold rotational axes oriented at 109.5° (the tetrahedral angle) with respect to each other. These threefold axes lie along the body diagonals of the cube. The other six lattice systems, are hexagonal, tetragonal, rhombohedral (often confused with the trigonal crystal system), orthorhombic, monoclinic and triclinic.

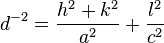

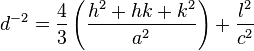

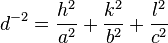

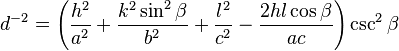

Reciprocal spacing

The spacing d between adjacent (hkl) lattice planes is

Cubic:

Tetragonal:

Hexagonal:

Rhombohedral:

Orthorhombic:

Monoclinic:

Triclinic:

Atomic coordination

By considering the arrangement of atoms relative to each other, their coordination numbers (or number of nearest neighbors), interatomic distances, types of bonding, etc., it is possible to form a general view of the structures and alternative ways of visualizing them.[7]

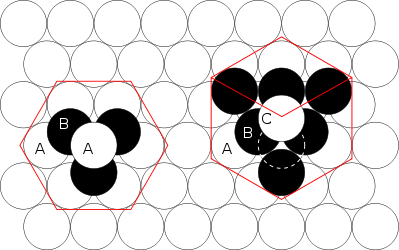

Close packing

The principles involved can be understood by considering the most efficient way of packing together equal-sized spheres and stacking close-packed atomic planes in three dimensions. For example, if plane A lies beneath plane B, there are two possible ways of placing an additional atom on top of layer B. If an additional layer was placed directly over plane A, this would give rise to the following series :

This arrangement of atoms in a crystal structure is known as hexagonal close packing (hcp).

If, however, all three planes are staggered relative to each other and it is not until the fourth layer is positioned directly over plane A that the sequence is repeated, then the following sequence arises:

This type of structural arrangement is known as cubic close packing (ccp).

The unit cell of a ccp arrangement of atoms is the face-centered cubic (fcc) unit cell. This is not immediately obvious as the closely packed layers are parallel to the {111} planes of the fcc unit cell. There are four different orientations of the close-packed layers.

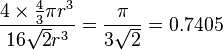

The packing efficiency can be worked out by calculating the total volume of the spheres and dividing by the volume of the cell as follows:

The 74% packing efficiency is the maximum density possible in unit cells constructed of spheres of only one size. Most crystalline forms of metallic elements are hcp, fcc, or bcc (body-centered cubic). The coordination number of atoms in hcp and fcc structures is 12 and its atomic packing factor (APF) is the number mentioned above, 0.74. This can be compared to the APF of a bcc structure, which is 0.68.

Bravais lattices

When the crystal systems are combined with the various possible lattice centerings, we arrive at the Bravais lattices.[5] They describe the geometric arrangement of the lattice points, and thereby the translational symmetry of the crystal. In three dimensions, there are 14 unique Bravais lattices that are distinct from one another in the translational symmetry they contain. All crystalline materials recognized until now (not including quasicrystals) fit in one of these arrangements. The fourteen three-dimensional lattices, classified by crystal system, are shown above. The Bravais lattices are sometimes referred to as space lattices.

The crystal structure consists of the same group of atoms, the basis, positioned around each and every lattice point. This group of atoms therefore repeats indefinitely in three dimensions according to the arrangement of one of the 14 Bravais lattices. The characteristic rotation and mirror symmetries of the group of atoms, or unit cell, is described by its crystallographic point group.

Point groups

The crystallographic point group or crystal class is the mathematical group comprising the symmetry operations that leave at least one point unmoved and that leave the appearance of the crystal structure unchanged. These symmetry operations include

- Reflection, which reflects the structure across a reflection plane

- Rotation, which rotates the structure a specified portion of a circle about a rotation axis

- Inversion, which changes the sign of the coordinate of each point with respect to a center of symmetry or inversion point

- Improper rotation, which consists of a rotation about an axis followed by an inversion.

Rotation axes (proper and improper), reflection planes, and centers of symmetry are collectively called symmetry elements. There are 32 possible crystal classes. Each one can be classified into one of the seven crystal systems.

Space groups

In addition to the operations of the point group, the space group of the crystal structure contains translational symmetry operations. These include:

- Pure translations, which move a point along a vector

- Screw axes, which rotate a point around an axis while translating parallel to the axis.[8]

- Glide planes, which reflect a point through a plane while translating it parallel to the plane.[8]

There are 230 distinct space groups.

Grain boundaries

Grain boundaries are interfaces where crystals of different orientations meet.[5] A grain boundary is a single-phase interface, with crystals on each side of the boundary being identical except in orientation. The term "crystallite boundary" is sometimes, though rarely, used. Grain boundary areas contain those atoms that have been perturbed from their original lattice sites, dislocations, and impurities that have migrated to the lower energy grain boundary.

Treating a grain boundary geometrically as an interface of a single crystal cut into two parts, one of which is rotated, we see that there are five variables required to define a grain boundary. The first two numbers come from the unit vector that specifies a rotation axis. The third number designates the angle of rotation of the grain. The final two numbers specify the plane of the grain boundary (or a unit vector that is normal to this plane).[7]

Grain boundaries disrupt the motion of dislocations through a material, so reducing crystallite size is a common way to improve strength, as described by the Hall–Petch relationship. Since grain boundaries are defects in the crystal structure they tend to decrease the electrical and thermal conductivity of the material. The high interfacial energy and relatively weak bonding in most grain boundaries often makes them preferred sites for the onset of corrosion and for the precipitation of new phases from the solid. They are also important to many of the mechanisms of creep.[7]

Grain boundaries are in general only a few nanometers wide. In common materials, crystallites are large enough that grain boundaries account for a small fraction of the material. However, very small grain sizes are achievable. In nanocrystalline solids, grain boundaries become a significant volume fraction of the material, with profound effects on such properties as diffusion and plasticity. In the limit of small crystallites, as the volume fraction of grain boundaries approaches 100%, the material ceases to have any crystalline character, and thus becomes an amorphous solid.[7]

Defects and impurities

Real crystals feature defects or irregularities in the ideal arrangements described above and it is these defects that critically determine many of the electrical and mechanical properties of real materials. When one atom substitutes for one of the principal atomic components within the crystal structure, alteration in the electrical and thermal properties of the material may ensue.[9] Impurities may also manifest as spin impurities in certain materials. Research on magnetic impurities demonstrates that substantial alteration of certain properties such as specific heat may be affected by small concentrations of an impurity, as for example impurities in semiconducting ferromagnetic alloys may lead to different properties as first predicted in the late 1960s.[10][11] Dislocations in the crystal lattice allow shear at lower stress than that needed for a perfect crystal structure.[12]

Prediction of structure

The difficulty of predicting stable crystal structures based on the knowledge of only the chemical composition has long been a stumbling block on the way to fully computational materials design. Now, with more powerful algorithms and high-performance computing, structures of medium complexity can be predicted using such approaches as evolutionary algorithms, random sampling, or metadynamics.

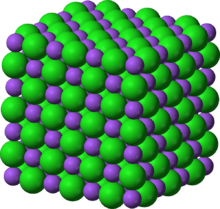

The crystal structures of simple ionic solids (e.g., NaCl or table salt) have long been rationalized in terms of Pauling's rules, first set out in 1929 by Linus Pauling, referred to by many since as the "father of the chemical bond".[13] Pauling also considered the nature of the interatomic forces in metals, and concluded that about half of the five d-orbitals in the transition metals are involved in bonding, with the remaining nonbonding d-orbitals being responsible for the magnetic properties. He, therefore, was able to correlate the number of d-orbitals in bond formation with the bond length as well as many of the physical properties of the substance. He subsequently introduced the metallic orbital, an extra orbital necessary to permit uninhibited resonance of valence bonds among various electronic structures.[14]

In the resonating valence bond theory, the factors that determine the choice of one from among alternative crystal structures of a metal or intermetallic compound revolve around the energy of resonance of bonds among interatomic positions. It is clear that some modes of resonance would make larger contributions (be more mechanically stable than others), and that in particular a simple ratio of number of bonds to number of positions would be exceptional. The resulting principle is that a special stability is associated with the simplest ratios or "bond numbers": 1/2, 1/3, 2/3, 1/4, 3/4, etc. The choice of structure and the value of the axial ratio (which determines the relative bond lengths) are thus a result of the effort of an atom to use its valency in the formation of stable bonds with simple fractional bond numbers.[15][16]

After postulating a direct correlation between electron concentration and crystal structure in beta-phase alloys, Hume-Rothery analyzed the trends in melting points, compressibilities and bond lengths as a function of group number in the periodic table in order to establish a system of valencies of the transition elements in the metallic state. This treatment thus emphasized the increasing bond strength as a function of group number.[17] The operation of directional forces were emphasized in one article on the relation between bond hybrids and the metallic structures. The resulting correlation between electronic and crystalline structures is summarized by a single parameter, the weight of the d-electrons per hybridized metallic orbital. The "d-weight" calculates out to 0.5, 0.7 and 0.9 for the fcc, hcp and bcc structures respectively. The relationship between d-electrons and crystal structure thus becomes apparent.[18]

In crystal structure predictions/simulations, the periodicity is usually applied, since the system is imagined as unlimited big in all directions. Starting from a triclinic structure with no further symmetry property assumed, the system may be driven to show some additional symmetry properties by applying Newton's Second Law on particles in the unit cell and a recently developed dynamical equation for the system period vectors [19] (lattice parameters including angles), even if the system is subject to external stress.

Polymorphism

Polymorphism refers to the ability of a solid to exist in more than one crystalline form or structure. According to Gibbs' rules of phase equilibria, these unique crystalline phases will be dependent on intensive variables such as pressure and temperature. Polymorphism can potentially be found in many crystalline materials including polymers, minerals, and metals, and is related to allotropy, which refers to elemental solids. The complete morphology of a material is described by polymorphism and other variables such as crystal habit, amorphous fraction or crystallographic defects. Polymorphs have different stabilities and may spontaneously convert from a metastable form (or thermodynamically unstable form) to the stable form at a particular temperature. They also exhibit different melting points, solubilities, and X-ray diffraction patterns.

One good example of this is the quartz form of silicon dioxide, or SiO2. In the vast majority of silicates, the Si atom shows tetrahedral coordination by 4 oxygens. All but one of the crystalline forms involve tetrahedral SiO4 units linked together by shared vertices in different arrangements. In different minerals the tetrahedra show different degrees of networking and polymerization. For example, they occur singly, joined together in pairs, in larger finite clusters including rings, in chains, double chains, sheets, and three-dimensional frameworks. The minerals are classified into groups based on these structures. In each of its 7 thermodynamically stable crystalline forms or polymorphs of crystalline quartz, only 2 out of 4 of each the edges of the SiO4 tetrahedra are shared with others, yielding the net chemical formula for silica: SiO2.

Another example is elemental tin (Sn), which is malleable near ambient temperatures but is brittle when cooled. This change in mechanical properties due to existence of its two major allotropes, α- and β-tin. The two allotropes that are encountered at normal pressure and temperature, α-tin and β-tin, are more commonly known as gray tin and white tin respectively. Two more allotropes, γ and σ, exist at temperatures above 161 °C and pressures above several GPa.[20] White tin is metallic, and is the stable crystalline form at or above room temperature. Below 13.2 °C, tin exists in the gray form, which has a diamond cubic crystal structure, similar to diamond, silicon or germanium. Gray tin has no metallic properties at all, is a dull-gray powdery material, and has few uses, other than a few specialized semiconductor applications.[21] Although the α-β transformation temperature of tin is nominally 13.2 °C, impurities (e.g. Al, Zn, etc.) lower the transition temperature well below 0 °C, and upon addition of Sb or Bi the transformation may not occur at all.[22]

Physical properties

Twenty of the 32 crystal classes are piezoelectric, and crystals belonging to one of these classes (point groups) display piezoelectricity. All piezoelectric classes lack a centre of symmetry. Any material develops a dielectric polarization when an electric field is applied, but a substance that has such a natural charge separation even in the absence of a field is called a polar material. Whether or not a material is polar is determined solely by its crystal structure. Only 10 of the 32 point groups are polar. All polar crystals are pyroelectric, so the 10 polar crystal classes are sometimes referred to as the pyroelectric classes.

There are a few crystal structures, notably the perovskite structure, which exhibit ferroelectric behavior. This is analogous to ferromagnetism, in that, in the absence of an electric field during production, the ferroelectric crystal does not exhibit a polarization. Upon the application of an electric field of sufficient magnitude, the crystal becomes permanently polarized. This polarization can be reversed by a sufficiently large counter-charge, in the same way that a ferromagnet can be reversed. However, although they are called ferroelectrics, the effect is due to the crystal structure (not the presence of a ferrous metal).

See also

- Brillouin zone

- Crystal engineering

- Crystal growth

- Crystallographic database

- Fractional coordinates

- Frank Kasper phases

- Hermann–Mauguin notation

- Laser-heated pedestal growth

- Liquid crystal

- Patterson function

- Periodic table (crystal structure)

- Primitive cell

- Schoenflies notation

- Seed crystal

- Wigner–Seitz cell

References

- ↑ Physics of Ice, V. F. Petrenko, R. W. Whitworth, Oxford University Press, 1999, ISBN 9780198518945

- ↑ Bernal, J. D. and Fowler, R. H. (1933). "A Theory of Water and Ionic Solution, with Particular Reference to Hydrogen and Hydroxyl Ions". The Journal of Chemical Physics 1 (8): 515. Bibcode:1933JChPh...1..515B. doi:10.1063/1.1749327.

- 1 2 3 Solid State Physics (2nd Edition), J.R. Hook, H.E. Hall, Manchester Physics Series, John Wiley & Sons, 2010, ISBN 978-0-471-92804-1

- ↑ International Tables for Crystallography (2006). Volume A, Space-group symmetry.

- 1 2 3 Encyclopaedia of Physics (2nd Edition), R.G. Lerner, G.L. Trigg, VHC publishers, 1991, ISBN (Verlagsgesellschaft) 3-527-26954-1, ISBN (VHC Inc.) 0-89573-752-3

- ↑ Ashcroft, N.; Mermin, D. (1976) Solid State Physics, Brooks/Cole (Thomson Learning, Inc.), Chapter 7, ISBN 0-03-049346-3

- 1 2 3 4 McGraw Hill Encyclopaedia of Physics (2nd Edition), C.B. Parker, 1994, ISBN 0-07-051400-3

- 1 2 Donald E. Sands (1994). "§4-2 Screw axes and §4-3 Glide planes". Introduction to Crystallography (Reprint of WA Benjamin corrected 1975 ed.). Courier-Dover. pp. 70–71. ISBN 0486678393.

- ↑ Nikola Kallay (2000) Interfacial Dynamics, CRC Press, ISBN 0-8247-0006-6

- ↑ Hogan, C. M. (1969). "Density of States of an Insulating Ferromagnetic Alloy". Physical Review 188 (2): 870. Bibcode:1969PhRv..188..870H. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.188.870.

- ↑ Zhang, X. Y.; Suhl, H (1985). "Spin-wave-related period doublings and chaos under transverse pumping". Physical Review A 32 (4): 2530–2533. Bibcode:1985PhRvA..32.2530Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.32.2530. PMID 9896377.

- ↑ Courtney, Thomas (2000). Mechanical Behavior of Materials. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press. p. 85. ISBN 1-57766-425-6.

- ↑ L. Pauling (1929). "The principles determining the structure of complex ionic crystals". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 51 (4): 1010–1026. doi:10.1021/ja01379a006.

- ↑ Pauling, Linus (1938). "The Nature of the Interatomic Forces in Metals". Physical Review 54 (11): 899. Bibcode:1938PhRv...54..899P. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.54.899.

- ↑ Pauling, Linus (1947). "Atomic Radii and Interatomic Distances in Metals". Journal of the American Chemical Society 69 (3): 542. doi:10.1021/ja01195a024.

- ↑ Pauling, L. (1949). "A Resonating-Valence-Bond Theory of Metals and Intermetallic Compounds". Proceedings of the Royal Society A 196 (1046): 343. Bibcode:1949RSPSA.196..343P. doi:10.1098/rspa.1949.0032.

- ↑ Hume-rothery, W.; Irving, H. M.; Williams, R. J. P. (1951). "The Valencies of the Transition Elements in the Metallic State". Proceedings of the Royal Society A 208 (1095): 431. Bibcode:1951RSPSA.208..431H. doi:10.1098/rspa.1951.0172.

- ↑ Altmann, S. L.; Coulson, C. A.; Hume-Rothery, W. (1957). "On the Relation between Bond Hybrids and the Metallic Structures". Proceedings of the Royal Society A 240 (1221): 145. Bibcode:1957RSPSA.240..145A. doi:10.1098/rspa.1957.0073.

- ↑ Liu, Gang (2015). "Dynamical equations for the period vectors in a periodic system under constant external stress". Can. J. Phys. 93 (9): 974. doi:10.1139/cjp-2014-0518.

- ↑ Molodets, A. M.; Nabatov, S. S. (2000). "Thermodynamic Potentials, Diagram of State, and Phase Transitions of Tin on Shock Compression". High Temperature 38 (5): 715–721. doi:10.1007/BF02755923.

- ↑ Holleman, Arnold F.; Wiberg, Egon; Wiberg, Nils (1985). "Tin". Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie (in German) (91–100 ed.). Walter de Gruyter. pp. 793–800. ISBN 3-11-007511-3.

- ↑ Schwartz, Mel (2002). "Tin and Alloys, Properties". Encyclopedia of Materials, Parts and Finishes (2nd ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 1-56676-661-3.

External links

- The internal structure of crystals... Crystallography for beginners

- Appendix A from the manual for Atoms, software for XAFS

- Intro to Minerals: Crystal Class and System

- Introduction to Crystallography and Mineral Crystal Systems

- Crystal planes and Miller indices

- Interactive 3D Crystal models

- Specific Crystal 3D models

- Crystallography Open Database (with more than 140.000 crystal structures)

- Crystal Lattice Structures: Other Crystal Structure Web Sites

|