Cryptorchidism

| Cryptorchidism | |

|---|---|

| |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | medical genetics |

| ICD-10 | Q53 |

| ICD-9-CM | 752.5 |

| OMIM | 219050 |

| DiseasesDB | 3218 |

| MedlinePlus | 000973 |

| eMedicine | med/2707 radio/201 ped/3080 |

| MeSH | D003456 |

Cryptorchidism (derived from the Greek κρυπτός, kryptos, meaning hidden ὄρχις, orchis, meaning testicle) is the absence of one or both testes from the scrotum. It is the most common birth defect of the male genitalia.[1] In unique cases, cryptorchidism can develop later in life, often as late as young adulthood. About 3% of full-term and 30% of premature infant boys are born with at least one undescended testis. However, about 80% of cryptorchid testes descend by the first year of life (the majority within three months), making the true incidence of cryptorchidism around 1% overall. Cryptorchidism is distinct from monorchism, the condition of having only one testicle.

A testis absent from the normal scrotal position can be found:

- along the "path of descent" from high in the posterior (retroperitoneal) abdomen, just below the kidney, to the inguinal ring;

- in the inguinal canal;

- ectopically, that is, to have "wandered" from that path, usually outside the inguinal canal and sometimes even under the skin of the thigh, the perineum, the opposite scrotum, or the femoral canal;

- undeveloped (hypoplastic) or severely abnormal (dysgenetic);

- to have vanished (also see anorchia).

About two thirds of cases without other abnormalities are unilateral; one third involve both testes. In 90% of cases an undescended testis can be felt in the inguinal canal; in a minority the testis or testes are in the abdomen or nonexistent (truly "hidden").

Undescended testes are associated with reduced fertility, increased risk of testicular germ cell tumors and psychological problems when the boy is grown. Undescended testes are also more susceptible to testicular torsion (and subsequent infarction) and inguinal hernias. Without intervention, an undescended testicle will usually descend during the first year of life, but to reduce these risks, undescended testes can be brought into the scrotum in infancy by a surgical procedure called an orchiopexy.[2]

Although cryptorchidism nearly always refers to congenital absence or maldescent, a testis observed in the scrotum in early infancy can occasionally "reascend" (move back up) into the inguinal canal. A testis which can readily move or be moved between the scrotum and canal is referred to as retractile.

Normal fetal testicular development and descent

The testes begin as an immigration of primordial germ cells into testicular cords along the gonadal ridge in the abdomen of the early embryo. The interaction of several male genes organizes this developing gonad into a testis rather than an ovary by the second month of gestation. During the 3rd to 5th months, the cells in the testes differentiate into testosterone-producing Leydig cells, and anti-Müllerian hormone-producing Sertoli cells. The germ cells in this environment become fetal spermatogonia. Male external genitalia develop during the 3rd and 4th months of gestation and the fetus continues to grow, develop, and differentiate. The testes remain high in the abdomen until the 7th month of gestation, when they move from the abdomen through the inguinal canals into the two sides of the scrotum. It has been proposed that movement occurs in two phases, under control of somewhat different factors. The first phase, movement across the abdomen to the entrance of the inguinal canal appears controlled (or at least greatly influenced) by anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH). The second phase, in which the testes move through the inguinal canal into the scrotum, is dependent on androgens (most importantly testosterone). In rodents, androgens induce the genitofemoral nerve to release calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), which produces rhythmic contractions of the gubernaculum, a ligament which connects the testis to the scrotum, but a similar mechanism has not been demonstrated in humans. Maldevelopment of the gubernaculum, or deficiency or insensitivity to either AMH or androgen can therefore prevent the testes from descending into the scrotum. Some evidence suggests there may even be an additional paracrine hormone, referred to as descendin, secreted by the testes.

In many infants with inguinal testes, further descent of the testes into the scrotum occurs in the first 6 months of life. This is attributed to the postnatal surge of gonadotropins and testosterone that normally occurs between the first and fourth months of life.

Spermatogenesis continues after birth. In the 3rd to 5th months of life, some of the fetal spermatogonia residing along the basement membrane become type A spermatogonia. More gradually, other fetal spermatogonia become type B spermatogonia and primary spermatocytes by the 5th year after birth. Spermatogenesis arrests at this stage until puberty.

Most normal-appearing undescended testis are also normal by microscopic examination, but reduced spermatogonia can be found. The tissue in undescended testes becomes more markedly abnormal ("degenerates") in microscopic appearance between 2 and 4 years after birth. There is some evidence that early orchiopexy reduces this degeneration.

Causes and risk factors

In most full-term infant boys with cryptorchidism but no other genital abnormalities, a cause cannot be found, making this a common, sporadic, unexplained (idiopathic) birth defect. A combination of genetics, maternal health and other environmental factors may disrupt the hormones and physical changes that influence the development of the testicles.

- Severely premature infants can be born before descent of testes. Low birth weight is also a known factor.[3]

- A contributing role of environmental chemicals called endocrine disruptors that interfere with normal fetal hormone balance has been proposed. The Mayo Clinic lists "parents' exposure to some pesticides" as a known risk factor.[3][4]

- Diabetes and obesity in the mother.[3]

- Risk factors may include exposure to regular alcohol consumption during pregnancy (5 or more drinks per week, associated with a 3x increase in cryptorchidism, when compared to non-drinking mothers.[5] Cigarette smoking is also a known risk factor.[3]

- Family history of undescended testicle or other problems of genital development.[3]

- Cryptorchidism occurs at a much higher rate in a large number of congenital malformation syndromes. Among the more common are Down syndrome[3] Prader–Willi syndrome, and Noonan syndrome.

- In vitro fertilization, use of cosmetics by the mother, and preeclampsia have also been recognized as risk factors for development of cryptorchidism.[6]

In 2008 a study was published that investigated the possible relationship between cryptorchidism and prenatal exposure to a chemical called phthalate (DEHP) which is used in the manufacture of plastics. The researchers found a significant association between higher levels of DEHP metabolites in the pregnant mothers and several sex-related changes, including incomplete descent of the testes in their sons. According to the lead author of the study, a national survey found that 25% of U.S. women had phthalate levels similar to the levels that were found to be associated with sexual abnormalities.[7]

A 2010 study published in the European medical journal Human Reproduction examined the prevalence of congenital cryptorchidism among offspring whose mothers had taken mild analgesics, primarily over-the-counter pain medications including ibuprofen (e.g. Advil) and paracetamol (acetaminophen).[8] Combining the results from a survey of pregnant women prior to their due date in correlation with the health of their children and an ex vivo rat model, the study found that pregnant women who had been exposed to mild analgesics had a higher prevalence of baby boys born with congenital cryptorchidism.[8][9]

New insight into the testicular descent mechanism has been hypothesized by the concept of a male programming window (MPW) derived from animal studies. According to this concept, testicular descent status is "set" during the period from 8 to 14 weeks of gestation in humans. Undescended testis is a result of disruption in androgen levels only during this programming window.[10]

Diagnosis

The most common diagnostic dilemma in otherwise normal boys is distinguishing a retractile testis from a testis that will not/cannot descend spontaneously into the scrotum. Retractile testes are more common than truly undescended testes and do not need to be operated on. In normal males, as the cremaster muscle relaxes or contracts, the testis moves lower or higher ("retracts") in the scrotum. This cremasteric reflex is much more active in infant boys than older men. A retractile testis high in the scrotum can be difficult to distinguish from a position in the lower inguinal canal. Though there are various maneuvers used to do so, such as using a crosslegged position, soaping the examiner's fingers, or examining in a warm bath, the benefit of surgery in these cases can be a matter of clinical judgement.

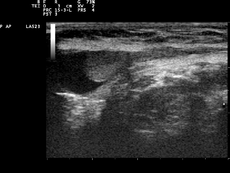

In the minority of cases with bilaterally non-palpable testes, further testing to locate the testes, assess their function, and exclude additional problems is often useful. Pelvic ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging performed and interpreted by a radiologist can often, but not invariably, locate the testes while confirming absence of a uterus. A karyotype can confirm or exclude forms of dysgenetic primary hypogonadism, such as Klinefelter syndrome or mixed gonadal dysgenesis. Hormone levels (especially gonadotropins and AMH) can help confirm that there are hormonally functional testes worth attempting to rescue, as can stimulation with a few injections of human chorionic gonadotropin to elicit a rise of the testosterone level. Occasionally these tests reveal an unsuspected and more complicated intersex condition.

In the even smaller minority of cryptorchid infants who have other obvious birth defects of the genitalia, further testing is crucial and has a high likelihood of detecting an intersex condition or other anatomic anomalies. Ambiguity can indicate either impaired androgen synthesis or reduced sensitivity. The presence of a uterus by pelvic ultrasound suggests either persistent Müllerian duct syndrome (AMH deficiency or insensitivity) or a severely virilized genetic female with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. An unambiguous micropenis, especially accompanied by hypoglycemia or jaundice, suggests congenital hypopituitarism.

Treatment

The primary management of cryptorchidism is watchful waiting, due to the high likelihood of self-resolution. Where this fails, a surgery, called orchiopexy, is effective if inguinal testes have not descended after 4–6 months. Surgery is often performed by a pediatric urologist or pediatric surgeon, but in many communities still by a general urologist or surgeon.

When the undescended testis is in the inguinal canal, hormonal therapy is sometimes attempted and very occasionally successful. The most commonly used hormone therapy is human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG). A series of hCG injections (10 injections over 5 weeks is common) is given and the status of the testis/testes is reassessed at the end. Although many trials have been published, the reported success rates range widely, from roughly 5 to 50%, probably reflecting the varying criteria for distinguishing retractile testes from low inguinal testes. Hormone treatment does have the occasional incidental benefits of allowing confirmation of Leydig cell responsiveness (proven by a rise of the testosterone by the end of the injections) or inducing additional growth of a small penis (via the testosterone rise). Some surgeons have reported facilitation of surgery, perhaps by enhancing the size, vascularity, or healing of the tissue. A newer hormonal intervention used in Europe is use of GnRH analogs such as nafarelin or buserelin; the success rates and putative mechanism of action are similar to hCG, but some surgeons have combined the two treatments and reported higher descent rates. Limited evidence suggests that germ cell count is slightly better after hormone treatment; whether this translates into better sperm counts and fertility rates at maturity has not been established. The cost of either type of hormone treatment is less than that of surgery and the chance of complications at appropriate doses is minimal. Nevertheless, despite the potential advantages of a trial of hormonal therapy, many surgeons do not consider the success rates high enough to be worth the trouble since the surgery itself is usually simple and uncomplicated.

In cases where the testes are identified preoperatively in the inguinal canal, orchiopexy is often performed as an outpatient and has a very low complication rate. An incision is made over the inguinal canal. The testis with accompanying cord structure and blood supply is exposed, partially separated from the surrounding tissues ("mobilized"), and brought into the scrotum. It is sutured to the scrotal tissue or enclosed in a "subdartos pouch." The associated passage back into the inguinal canal, an inguinal hernia, is closed to prevent re-ascent. In patients with intraabdominal maldescended testis, laparoscopy is useful to see for oneself the pelvic structures, position of the testis and decide upon surgery ( single or staged procedure ).

Surgery becomes more complicated if the blood supply is not ample and elastic enough to be stretched into the scrotum. In these cases, the supply may be divided, some vessels sacrificed with expectation of adequate collateral circulation. In the worst case, the testis must be "auto-transplanted" into the scrotum, with all connecting blood vessels cut and reconnected ("anastomosed").

When the testis is in the abdomen, the first stage of surgery is exploration to locate it, assess its viability, and determine the safest way to maintain or establish the blood supply. Multi-stage surgeries, or auto-transplantation and anastomosis, are more often necessary in these situations. Just as often, intra-abdominal exploration discovers that the testis is non-existent ("vanished"), or dysplastic and not salvageable.

The principal major complication of all types of orchiopexy is loss of the blood supply to the testis, resulting in loss of the testis due to ischemic atrophy or fibrosis.

Psychological consequences

There is a small body of research on the psychology of cryptorchidism, that attempts to determine whether this condition can cause lasting psychological problems. The psychological research on cryptorchism consists of only a few case reports and small studies. This research also suffers from serious methodological problems: major variables are completely uncontrolled, such as the small physical stature of many cryptorchid boys, and the psychological effects of corrective surgery.

Despite these research limitations, a few important results do emerge. Several psychoanalytic case studies indicated that cryptorchism by itself would not produce psychological disorder; but when combined with a common distinctive family pathology it did produce typical symptoms.[11] The most striking dynamic in this small sample were the parents’ contradictory attitude to the boy’s problem: a worried preoccupation with the genitals—constant poking, checking, and medical exams—conjoined with blatant denial that anything was wrong. The mothers were controlling and discouraged boyish aggression; the fathers were remote and dissatisfied with their son whose physical defect was equated to their own personal failures. In a research study similar family pattern were observed. The mothers of these cryptorchid boys tended to be possessive and regarded them as inadequate. The fathers were uninvolved and disparaging, and worried that the boy was a sissy or a freak.[12]

Interest in the psychology of cryptorchism has focused especially on the question whether the defect would cause pathology in the boy’s masculinity, male self-image, and sexual orientation. Blos (1960) noted that themes of castration and defective maleness were prominent in his cases. These boys were passive, shrank from boyish competition, and were accident-prone. However, despite these problems the boys did not have a core gender disorder. Sexual confusion was limited to the testicles, so that normal masculinity was arrested but then asserted itself after corrective surgery. Similar conclusions were reached in the research study by Cytryn, et al. (1967). The boys’ figure drawings showed poor sexual differentiation, were often missing limbs, or portrayed males as inferior to females. Over half the boys "seemed to see themselves as masculine but maimed or incomplete in some essential way" (p. 146.)

A related finding is that a thrust of masculine development is evidenced in cryptorchid boys upon repair of the undescended testicles. In each of Blos’ cases corrective surgery produced a euphoric upsurge of male sexuality followed by major advances in assertiveness, learning, and socializing. A similar outcome was reported with a 9-year-old Puerto Rican boy.[13] In another case study, a cryptorchid man in his twenties had successful surgery: his operation unleashed a wave of adolescent male strivings, as though the testicles represented "the masculine resources he always had within himself if he only had the courage to express and assert them."[14]

Friedman reported the case of a 7-year-old cryptorchid boy he treated for anxieties and immaturity.[15] This boy's mother, unlike the pathogenic stereotype, approved of his normal boyish behaviors. The cryptorchism was surgically corrected during treatment and resulted in the usual burst of masculine confidence and aggressiveness. This was directed at the therapist and gradually resolved in play therapy. The boy completed treatment successfully and developed into a psychologically healthy teenager.

In summary, existing research indicates that boys with undescended testicles do not tend to be gender-disordered, effeminate, or prehomosexual. A disturbed self-image forms only when the family dynamics are destructive to developing male self-esteem. Such pathogenic attitudes were found in parents who focused on the boy’s genital defect as a sign of his presumed effeminacy. However, when the cryptorchism is surgically corrected a healthy masculinity becomes possible. The basic sexual normality of these boys was confirmed in a small retrospective study that tested adolescent boys several years after their condition was surgically repaired. They had developed into fairly well adjusted teenagers without special sexual or gender problems, and with no distinctive traits of psychopathological relevance.[16]

Infertility

Prevalence

Many men who were born with undescended testes have reduced fertility, even after orchiopexy in infancy. The reduction with unilateral cryptorchidism is subtle, with a reported infertility rate of about 10%, compared with about 6% reported by the same study for the general population of adult men.

The fertility reduction after orchiopexy for bilateral cryptorchidism is more marked, about 38%, or 6 times that of the general population. The basis for the universal recommendation for early surgery is research showing degeneration of spermatogenic tissue and reduced spermatogonia counts after the second year of life in undescended testes. The degree to which this is prevented or improved by early orchiopexy is still uncertain.

Pathophysiology

At least one contributing mechanism for reduced spermatogenesis in cryptorchid testes is temperature. The temperature of testes in the scrotum is at least a couple of degrees cooler than in the abdomen. Animal experiments in the middle of the 20th century suggested that raising the temperature could damage fertility. Some circumstantial evidence suggests tight underwear and other practices that raise testicular temperature for prolonged periods can be associated with lower sperm counts. Nevertheless, research in recent decades suggests that the issue of fertility is more complex than a simple matter of temperature. It seems likely that subtle or transient hormone deficiencies or other factors that lead to lack of descent also impair the development of spermatogenic tissue.

The inhibition of spermatogenesis by ordinary intra-abdominal temperature is so potent that continual suspension of normal testes tightly against the inguinal ring at the top of the scrotum by means of special "suspensory briefs" has been researched as a method of male contraception, and was referred to as "artificial cryptorchidism" by one report.

An additional factor contributing to infertility is the high rate of anomalies of the epididymis in boys with cryptorchidism (over 90% in some studies). Even after orchiopexy, these may also affect sperm maturation and motility at an older age.

Later cancer risk

One of the strongest arguments for early orchiopexy is prevention of testicular cancer. About 1 in 500 men born with one or both testes undescended develop testicular cancer, roughly a 4 to 40 fold increased risk. The peak incidence occurs in the 3rd and 4th decades of life. The risk is higher for intra-abdominal testes and somewhat lower for inguinal testes, but even the normally descended testis of a man whose other testis was undescended has about a 20% higher cancer risk than those of other men.

The most common type of testicular cancer occurring in undescended testes is seminoma.[17] It is usually treatable if caught early, so urologists often recommend that boys who had orchiopexy as infants be taught testicular self-examination, to recognize testicular masses and seek early medical care for them. Cancer developing in an intra-abdominal testis would be unlikely to be recognized before considerable growth and spread, and one of the advantages of orchiopexy is that a mass developing in a scrotal testis is far easier to recognize than an intra-abdominal mass.

It was originally felt that orchidopexy resulted in easier detection of testis cancer but did not lower the risk of actually developing cancer. However, recent data has resulted in a paradigm shift. The New England Journal of Medicine published in 2007 that orchidopexy performed before puberty resulted in a significantly reduced risk of testicular cancer than if done after puberty.[18]

The risk of malignancy in the undescended testis is 4 to 10 times higher than that in the general population and is approximately 1 in 80 with a unilateral undescended testis and 1 in 40 to 1 in 50 for bilateral undescended testes. The peak age for this tumor is 15–45 yr. The most common tumor developing in an undescended testis is a seminoma (65%); in contrast, after orchiopexy, seminomas represent only 30% of testis tumors.

Veterinary occurrence

Dogs

Cryptorchidism is common in male dogs, occurring at a rate of up to 10%.[19] Although the genetics are not fully understood, it is thought to be a recessive, and probably polygenetic, trait.[20] Some have speculated that it is a sex-limited autosomal recessive trait;[21] however, it is unlikely to be simple recessive.[20] Dog testes usually descend by ten days of age and it is considered to be cryptorchidism if they do not descend by the age of eight weeks.[22] Cryptorchidism can be either bilateral (causing sterility) or unilateral, and inguinal or abdominal (or both). Because it is an inherited trait, affected dogs should not be bred and should be castrated. The parents should be considered carriers of the defect and a breeder should thoughtfully consider whether to breed the carrier parent or not. Littermates may be normal, carriers, or cryptorchid. Castration of the undescended teste(s) should be considered for cryptorchid dogs due to the high rate of testicular cancer, especially sertoli cell tumours.[22] The incidence of testicular cancer is 13.6 times higher in dogs with abdominally retained testicles compared with normal dogs.[19] Testicular torsion is also more likely in retained testicles. Surgical correction is by palpation of the retained testicle and subsequent exploration of the inguinal canal or abdomen, however it is against AKC rules to show altered dogs, making this correction pointless for breeding stock. Surgical correction is termed orchiopexy, i.e., a surgery to move an undescended testicle into the scrotum and permanently fix it there. Surgical correction is an option for pet dogs that will not be used for breeding.

Commonly affected breeds include:[21]

- Alaskan Klee Kai

- Boxer

- Chihuahua

- Dachshund (miniature)

- Bulldog

- Maltese

- Miniature Schnauzer

- Pekingese

- Pomeranian

- Poodle (toy and miniature)

- Pug

- Shetland Sheepdog

- Whippet

- Yorkshire Terrier

Cats

Cryptorchidism is rarer in cats than it is in dogs. In one study 1.9% of intact male cats were cryptorchid.[23] Persians are predisposed.[24] Normally the testicles are in the scrotum by the age of six to eight weeks. Urine spraying is one indication that a cat with no observable testicles may not be neutered; other signs are the presence of enlarged jowls, thickened facial and neck skin, and spines on the penis (which usually regress within six weeks after castration).[25] Most cryptorchid cats present with an inguinal testicle.[26] Testicular tumors and testicular torsion are rare in cryptorchid cats, but castration is usually performed due to unwanted behavior such as urine spraying.

Horses

In horses, cryptorchidism is sufficiently common that affected males (ridglings) are routinely gelded.

Rarely, cryptorchidism is due to the presence of a congenital testicular tumor such as a teratoma, which has a tendency to grow large.[27]

References

- ↑ Wood, HM; Elder, JS (February 2009). "Cryptorchidism and testicular cancer: separating fact from fiction.". The Journal of Urology 181 (2): 452–61. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2008.10.074. PMID 19084853.

- ↑ The A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/undescended-testicle/DS00845/DSECTION=risk-factors

- ↑ "PMC". nih.gov.

- ↑ "Drinking During Pregnancy Emerges As a Possible Male-Infertility Factor". Science News.

- ↑ Brouwers, Marijn M.; de Bruijne, Leonie M.; de Gier, Robert P.E.; Zielhuis, Gerhard A.; Feitz, Wouter F.J.; Roeleveld, Nel (2012). "Risk factors for undescended testis". Journal of Pediatric Urology 8 (1): 59–66. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2010.11.001.

- ↑ http://pubs.acs.org/action/showStoryContent?doi=10.1021%2Fon.2008.11.12.154968&

- 1 2 "Intrauterine exposure to mild analgesics is a risk factor for development of male reproductive disorders in human and rat" (PDF). oxfordjournals.org.

- ↑ Intrauterine exposure to mild analgesics is a risk factor for development of male reproductive disorders in human and rat, Human Reproduction, 2010, doi:10.1093/humrep/deq323

- ↑ Welsh, M.; Saunders, P. T.; et al. (2008). "Identification in rats of a programming window for reproductive tract masculinization, disruption of which leads to hypospadias and cryptorchidism". J Clin Invest 118 (4): 1479–1490. doi:10.1172/jci34241.

- ↑ Blos, P. (1960). Comments on the psychological consequences of cryptorchism. Psychoanal. Study Child, 15:395–429

- ↑ Cytryn, L, Cytryn, E., & Reiger, R. (1967). Psychological implications of cryptorchism. J. Amer. Acad. Child Psychiatry, 6:131–165

- ↑ Schiffman & Straker (1979). The psychological role of the testicles: a case report. J. Amer. Acad. Child Psychiatry, 18:521–526

- ↑ Druss, R. (1978). Cryptorchism and body image: the psychoanalysis of a case. J. Amer. Psychoanal. Assn., 30:161–180

- ↑ Friedman, R. (1996). The testicles in male psychological development. J. Amer. Psychoanal. Assn., 44:201–256

- ↑ Meyer-Bahlburg, et al (1974). Cryptorchism,development of gender identity and sex behavior. In Sex Differences in Behavior, ed. Friedman, Richart, & Vande Wiele. New York: Wiley

- ↑ Dähnert, Wolfgang (2011). Radiology Review Manual. 995.

- ↑ Pettersson, Andreas; Lorenzo Richiardi; Agneta Nordenskjold; Magnus Kaijser; Olof Akre (May 3, 2007). "Age at Surgery for Undescended Testis and Risk of Testicular Cancer". NEJM 356 (18): 1835–41. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa067588. PMID 17476009.

- 1 2 Miller NA, Van Lue SJ, Rawlings CA (2004). "Use of laparoscopic-assisted cryptorchidectomy in dogs and cats". J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 224 (6): 875–8, 865. doi:10.2460/javma.2004.224.875. PMID 15070057.

- 1 2 Willis, Malcolm B. (1989). Genetics of the Dog (1st ed.). Howell Book House. ISBN 0-87605-551-X.

- 1 2 Ettinger, Stephen J.;Feldman, Edward C. (1995). Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine (4th ed.). W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 0-7216-6795-3.

- 1 2 Meyers-Wallen, V.N. "Inherited Abnormalities of Sexual Development in Dogs and Cats". Recent Advances in Small Animal Reproduction. Retrieved 2006-08-10.

- ↑ Scott K, Levy J, Crawford P (2002). "Characteristics of free-roaming cats evaluated in a trap-neuter-return program". J Am Vet Med Assoc 221 (8): 1136–8. doi:10.2460/javma.2002.221.1136. PMID 12387382.

- ↑ Griffin, Brenda (2005). "Diagnostic usefulness of and clinical syndromes associated with reproductive hormones". In August, John R. (ed.). Consultations in Feline Internal Medicine Vol. 5. Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-0423-4.

- ↑ Memon, M.; Tibary, A. (2001). "Canin and Feline Cryptorchidism" (PDF). Recent Advances in Small Animal Reproduction. Retrieved 2007-02-09.

- ↑ Yates D, Hayes G, Heffernan M, Beynon R (2003). "Incidence of cryptorchidism in dogs and cats". Vet Rec 152 (16): 502–4. doi:10.1136/vr.152.16.502. PMID 12733559.

- ↑ Jones, T. C., R. D. Hunt, and N. W. King (1997). Veterinary pathology (6th ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. p. 1392. ISBN 978-0-683-04481-2. page 1210.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||