Uncertainty quantification

Uncertainty quantification (UQ) is the science of quantitative characterization and reduction of uncertainties in both computational and real world applications. It tries to determine how likely certain outcomes are if some aspects of the system are not exactly known. An example would be to predict the acceleration of a human body in a head-on crash with another car: even if we exactly knew the speed, small differences in the manufacturing of individual cars, how tightly every bolt has been tightened, etc., will lead to different results that can only be predicted in a statistical sense.

Many problems in the natural sciences and engineering are also rife with sources of uncertainty. Computer experiments on computer simulations are the most common approach to study problems in uncertainty quantification.[1][2][3]

Sources of uncertainty

Uncertainty can enter mathematical models and experimental measurements in various contexts. One way to categorize the sources of uncertainty is to consider:[4]

- Parameter uncertainty, which comes from the model parameters that are inputs to the computer model (mathematical model) but whose exact values are unknown to experimentalists and cannot be controlled in physical experiments, or whose values cannot be exactly inferred by statistical methods. Examples are the local free-fall acceleration in a falling object experiment, various material properties in a finite element analysis for engineering, and multiplier uncertainty in the context of macroeconomic policy optimization.

- Parametric variability, which comes from the variability of input variables of the model. For example, the dimensions of a work piece in a process of manufacture may not be exactly as designed and instructed, which would cause variability in its performance.

- Structural uncertainty, aka model inadequacy, model bias, or model discrepancy, which comes from the lack of knowledge of the underlying true physics. It depends on how accurately a mathematical model describes the true system for a real-life situation, considering the fact that models are almost always only approximations to reality. One example is when modeling the process of a falling object using the free-fall model; the model itself is inaccurate since there always exists air friction. In this case, even if there is no unknown parameter in the model, a discrepancy is still expected between the model and true physics.

- Algorithmic uncertainty, aka numerical uncertainty, which comes from numerical errors and numerical approximations per implementation of the computer model. Most models are too complicated to solve exactly. For example, the finite element method or finite difference method may be used to approximate the solution of a partial differential equation, which, however, introduces numerical errors. Other examples are numerical integration and infinite sum truncation that are necessary approximations in numerical implementation.

- Experimental uncertainty, aka observation error, which comes from the variability of experimental measurements. The experimental uncertainty is inevitable and can be noticed by repeating a measurement for many times using exactly the same settings for all inputs/variables.

- Interpolation uncertainty, which comes from a lack of available data collected from computer model simulations and/or experimental measurements. For other input settings that don't have simulation data or experimental measurements, one must interpolate or extrapolate in order to predict the corresponding responses.

Aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty

It is sometimes assumed that uncertainty can be classified into two categories,[5][6] although the existence of this categorization is open to debate. These categories are prominently seen in medical applications.[7]

- Aleatoric uncertainty, aka statistical uncertainty, which is representative of unknowns that differ each time we run the same experiment. For example, a single arrow shot with a mechanical bow that exactly duplicates each launch (the same acceleration, altitude, direction and final velocity) will not all impact the same point on the target due to random and complicated vibrations of the arrow shaft, the knowledge of which cannot be determined sufficiently to eliminate the resulting scatter of impact points. The argument here is obviously in the definition of "cannot". Just because we cannot measure sufficiently with our currently available measurement devices does not preclude necessarily the existence of such information, which would move this uncertainty into the below category. Indeed, it is a philosophical question as to whether ‘aleatoric uncertainty’ is even a meaningful concept.

- Epistemic uncertainty, aka systematic uncertainty, which is due to things we could in principle know but don't in practice. This may be because we have not measured a quantity sufficiently accurately, or because our model neglects certain effects, or because particular data are deliberately hidden. An example of a source of this uncertainty would be the drag in an experiment designed to measure the acceleration of gravity near the earth's surface. The commonly used gravitational acceleration of 9.8 m/s^2 ignores the effects of air resistance, but the air resistance for the object could be measured and incorporated into the experiment to reduce the resulting uncertainty in the calculation of the gravitational acceleration.

In real life applications, both kinds of uncertainties are present. Uncertainty quantification intends to work toward reducing epistemic uncertainties to aleatoric uncertainties. The quantification for the aleatoric uncertainties can be relatively straightforward to perform, depending on the application. Techniques such as the Monte Carlo method are frequently used. A probability distribution can be represented by its moments (in the Gaussian case, the mean and covariance suffice, although it should be noted that, in general, even knowledge of all moments to arbitrarily high order still does not specify the distribution function uniquely), or more recently, by techniques such as Karhunen–Loève and polynomial chaos expansions. To evaluate epistemic uncertainties, the efforts are made to gain better knowledge of the system, process or mechanism. Methods such as fuzzy logic or evidence theory (Dempster–Shafer theory – a generalization of the Bayesian theory of subjective probability) are used.

Perhaps the most famous and mainstream reference to these two types of uncertainty was made in 2002 by then Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld, in his famous "There are known knowns" statement. When asked about weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, Rumsfeld referred to the situation as consisting of, among other things, "known unknowns" and "unknown unknowns". In this context the known unknowns were presumably epistemic uncertainty while the unknowns unknowns were aleatoric uncertainty. Filmmaker Errol Morris used a permutation of Rumsfeld's statement as the title of a documentary about Rumsfeld, The Unknown Known. The film focused heavily on Rumsfeld's statements about and understanding of uncertainty regarding the Iraq war.

Two types of uncertainty quantification problems

There are two major types of problems in uncertainty quantification: one is the forward propagation of uncertainty (where the various sources of uncertainty are propagated through the model to predict the overall uncertainty in the system response) and the other is the inverse assessment of model uncertainty and parameter uncertainty (where the model parameters are calibrated simultaneously using test data). There has been a proliferation of research on the former problem and a majority of uncertainty analysis techniques were developed for it. On the other hand, the latter problem is drawing increasing attention in the engineering design community, since uncertainty quantification of a model and the subsequent predictions of the true system response(s) are of great interest in designing robust systems.

Forward uncertainty propagation

Uncertainty propagation is the quantification of uncertainties in system output(s) propagated from uncertain inputs. It focuses on the influence on the outputs from the parametric variability listed in the sources of uncertainty. The targets of uncertainty propagation analysis can be:

- To evaluate low-order moments of the outputs, i.e. mean and variance.

- To evaluate the reliability of the outputs. This is especially useful in reliability engineering where outputs of a system are usually closely related to the performance of the system.

- To assess the complete probability distribution of the outputs. This is useful in the scenario of utility optimization where the complete distribution is used to calculate the utility.

Inverse uncertainty quantification

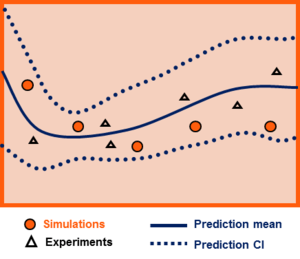

Given some experimental measurements of a system and some computer simulation results from its mathematical model, inverse uncertainty quantification estimates the discrepancy between the experiment and the mathematical model (which is called bias correction), and estimates the values of unknown parameters in the model if there are any (which is called parameter calibration or simply calibration). Generally this is a much more difficult problem than forward uncertainty propagation; however it is of great importance since it is typically implemented in a model updating process. There are several scenarios in inverse uncertainty quantification:

Bias correction only

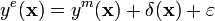

Bias correction quantifies the model inadequacy, i.e. the discrepancy between the experiment and the mathematical model. The general model updating formula for bias correction is:

where  denotes the experimental measurements as a function of several input variables

denotes the experimental measurements as a function of several input variables  ,

,  denotes the computer model (mathematical model) response,

denotes the computer model (mathematical model) response,  denotes the additive discrepancy function (aka bias function), and

denotes the additive discrepancy function (aka bias function), and  denotes the experimental uncertainty. The objective is to estimate the discrepancy function

denotes the experimental uncertainty. The objective is to estimate the discrepancy function  , and as a by-product, the resulting updated model is

, and as a by-product, the resulting updated model is  . A prediction confidence interval is provided with the updated model as the quantification of the uncertainty.

. A prediction confidence interval is provided with the updated model as the quantification of the uncertainty.

Parameter calibration only

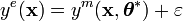

Parameter calibration estimates the values of one or more unknown parameters in a mathematical model. The general model updating formulation for calibration is:

where  denotes the computer model response that depends on several unknown model parameters

denotes the computer model response that depends on several unknown model parameters  , and

, and  denotes the true values of the unknown parameters in the course of experiments. The objective is to either estimate

denotes the true values of the unknown parameters in the course of experiments. The objective is to either estimate  , or to come up with a probability distribution of

, or to come up with a probability distribution of  that encompasses the best knowledge of the true parameter values.

that encompasses the best knowledge of the true parameter values.

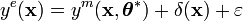

Bias correction and parameter calibration

It considers an inaccurate model with one or more unknown parameters, and its model updating formulation combines the two together:

It is the most comprehensive model updating formulation that includes all possible sources of uncertainty, and it requires the most effort to solve.

Selective methodologies for uncertainty quantification

Much research has been done to solve uncertainty quantification problems, though a majority of them deal with uncertainty propagation. During the past one to two decades, a number of approaches for inverse uncertainty quantification problems have also been developed and have proved to be useful for most small- to medium-scale problems.

Methodologies for forward uncertainty propagation

Existing uncertainty propagation approaches include probabilistic approaches and non-probabilistic approaches. There are basically five categories of probabilistic approaches for uncertainty propagation:[8]

- Simulation-based methods: Monte Carlo simulations, importance sampling, adaptive sampling, etc.

- Local expansion-based methods: Taylor series, perturbation method, etc. These methods have advantages when dealing with relatively small input variability and outputs that don't express high nonlinearity. These linear or linearized methods are detailed in the article Uncertainty propagation.

- Functional expansion-based methods: Neumann expansion, orthogonal or Karhunen-Loeve expansions (KLE), with polynomial chaos expansion (PCE) and wavelet expansions as special cases.

- Most probable point (MPP)-based methods: first-order reliability method (FORM) and second-order reliability method (SORM).

- Numerical integration-based methods: Full factorial numerical integration (FFNI) and dimension reduction (DR).

For non-probabilistic approaches, interval analysis [9] , Fuzzy theory, possibility theory and evidence theory are among the most widely used.

The probabilistic approach is considered as the most rigorous approach to uncertainty analysis in engineering design due to its consistency with the theory of decision analysis. Its cornerstone is the calculation of probability density functions for sampling statistics.[10] This can be performed rigorously for random variables that are obtainable as transformations of Gaussian variables, leading to exact confidence intervals.

Methodologies for inverse uncertainty quantification

Frequentist

In regression analysis and least squares problems, the standard error of parameter estimates is readily available, which can be expanded into a confidence interval.

Bayesian

Several methodologies for inverse uncertainty quantification exist under the Bayesian framework. The most complicated direction is to aim at solving problems with both bias correction and parameter calibration. The challenges of such problems include not only the influences from model inadequacy and parameter uncertainty, but also the lack of data from both computer simulations and experiments. A common situation is that the input settings are not the same over experiments and simulations.

Modular Bayesian approach

An approach to inverse uncertainty quantification is the modular Bayesian approach.[4][11] The modular Bayesian approach derives its name from its four-module procedure. Apart from the current available data, a prior distribution of unknown parameters should be assigned.

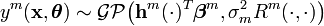

- Module 1: Gaussian process modeling for the computer model

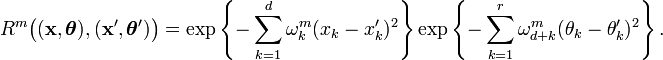

To address the issue from lack of simulation results, the computer model is replaced with a Gaussian Process (GP) model

where

is the dimension of input variables, and

is the dimension of input variables, and  is the dimension of unknown parameters.While

is the dimension of unknown parameters.While  is pre-defined,

is pre-defined,  , known as hyperparameters of the GP model, need to be estimated via maximum likelihood estimation (MLE). This module can be considered as a generalized Kriging method.

, known as hyperparameters of the GP model, need to be estimated via maximum likelihood estimation (MLE). This module can be considered as a generalized Kriging method.

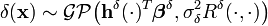

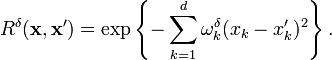

- Module 2: Gaussian process modeling for the discrepancy function

Similarly with the first module, the discrepancy function is replaced with a GP model

where

Together with the prior distribution of unknown parameters, and data from both computer models and experiments, one can derive the maximum likelihood estimates for  . At the same time,

. At the same time,  from Module 1 gets updated as well.

from Module 1 gets updated as well.

- Module 3: Posterior distribution of unknown parameters

Bayes' theorem is applied to calculate the posterior distribution of the unknown parameters:

where  includes all the fixed hyperparameters in previous modules.

includes all the fixed hyperparameters in previous modules.

- Module 4: Prediction of the experimental response and discrepancy function

Fully Bayesian approach

Fully Bayesian approach requires that not only the priors for unknown parameters  but also the priors for the other hyperparameters

but also the priors for the other hyperparameters  should be assigned. It follows the following steps:[12]

should be assigned. It follows the following steps:[12]

- Derive the posterior distribution

;

; - Integrate

out and obtain

out and obtain  . This single step accomplishes the calibration;

. This single step accomplishes the calibration; - Prediction of the experimental response and discrepancy function.

However, the approach has significant drawbacks:

- For most cases,

is a highly intractable function of

is a highly intractable function of  . Hence the integration becomes very troublesome. Moreover, if priors for the other hyperparameters

. Hence the integration becomes very troublesome. Moreover, if priors for the other hyperparameters  are not carefully chosen, the complexity in numerical integration increases even more.

are not carefully chosen, the complexity in numerical integration increases even more. - In the prediction stage, the prediction (which should at least include the expected value of system responses) also requires numerical integration. Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) is often used for integration; however it is computationally expensive.

The fully Bayesian approach requires a huge amount of calculations and may not yet be practical for dealing with the most complicated modelling situations.[12]

Known issues

The theories and methodologies for uncertainty propagation are much better established, compared with inverse uncertainty quantification. For the latter, several difficulties remain unsolved:

- Dimensionality issue: The computational cost increases dramatically with the dimensionality of the problem, i.e. the number of input variables and/or the number of unknown parameters.

- Identifiability issue:[13] Multiple combinations of unknown parameters and discrepancy function can yield the same experimental prediction. Hence different values of parameters cannot be distinguished/identified.

See also

References

- ↑ Jerome Sacks, William J. Welch, Toby J. Mitchell and Henry P. Wynn, Design and Analysis of Computer Experiments, Statistical Science, Vol. 4, No. 4 (Nov., 1989), pp. 409-423

- ↑ Ronald L. Iman, Jon C. Helton, An Investigation of Uncertainty and Sensitivity Analysis Techniques for Computer Models, Risk Analysis, Volume 8, Issue 1, pages 71–90, March 1988, DOI: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1988.tb01155.x

- ↑ W.E. Walker, P. Harremoës, J. Rotmans, J.P. van der Sluijs, M.B.A. van Asselt, P. Janssen and M.P. Krayer von Krauss, Defining Uncertainty: A Conceptual Basis for Uncertainty Management in Model-Based Decision Support, Integrated Assessment, Volume 4, Issue 1, 2003, DOI: 10.1076/iaij.4.1.5.16466

- 1 2 Marc C. Kennedy, Anthony O'Hagan, Bayesian calibration of computer models, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B Volume 63, Issue 3, pages 425–464, 2001

- ↑ Armen Der Kiureghiana, Ove Ditlevsen, Aleatory or epistemic? Does it matter?, Structural Safety, Volume 31, Issue 2, March 2009, Pages 105–112

- ↑ Hermann G. Matthies, Quantifying uncertainty: modern computational representation of probability and applications, Extreme Man-Made and Natural Hazards in Dynamics of Structures, NATO Security through Science Series, 2007, 105-135, DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4020-5656-7_4

- ↑ Abhaya Indrayan, "Medical Biostatistics, Second Edition", Chapman & Hall/CRC Press, 2008, pages 8, 673

- ↑ S. H. Lee and W. Chen, A comparative study of uncertainty propagation methods for black-box-type problems, Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization Volume 37, Number 3 (2009), 239-253, DOI: 10.1007/s00158-008-0234-7

- ↑ Jaulin, L.; Kieffer, M.; Didrit, O.; Walter, E. (2001). Applied Interval Analysis. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 1-85233-219-0.

- ↑ Arnaut, L. R. Measurement uncertainty in reverberation chambers - I. Sample statistics. Technical report TQE 2, 2nd. ed., sec. 3.1, National Physical Laboratory, 2008.

- ↑ Marc C. Kennedy, Anthony O'Hagan, Supplementary Details on Bayesian Calibration of Computer Models, Sheffield, University of Sheffield: 1-13, 2000

- 1 2 F. Liu, M.J. Bayarriy and J.O.Bergerz, Modularization in Bayesian Analysis, with Emphasis on Analysis of Computer Models, Bayesian Analysis (2009) 4, Number 1, pp. 119-150, DOI:10.1214/09-BA404

- ↑ Arendt, P., W. Chen, and D. Apley, Improving Identifiability in Model Calibration Using Multiple Responses, DETC2011-48623, ASME International Design Engineering Technical Conferences, August 28–31, Washington, D.C., 2011

Further reading

- da Silva, R.B., Bulska, E., Godlewska-Zylkiewicz, B., Hedrich, M., Majcen, N., Magnusson, B., Marincic, S., Papadakis, I., Patriarca, M., Vassileva, E., Taylor, P., Analytical measurement: measurement uncertainty and statistics; ISBN 978-92-79-23070-7, 2012.

- Arnaut, L. R. Measurement uncertainty in reverberation chambers - I. Sample statistics. Technical report TQE 2, 2nd. ed., National Physical Laboratory, 2008.