Ultra-Low Fouling

Surfaces are prone to contamination, which is a phenomenon known as fouling. Unwanted adsorbates caused by fouling change the properties of a surface, which is often counter-productive to the function of that surface. Consequently, a necessity for anti-fouling surfaces has arisen in many fields: blocked pipes inhibit factory productivity, biofouling increases fuel consumption on ships, medical devices must be kept sanitary, etc. Although chemical fouling inhibitors, metallic coatings, and cleaning processes can be used to reduce fouling, non-toxic surfaces with anti-fouling properties are ideal for fouling prevention. To be considered effective, an ultra-low fouling surface must be able repel and withstand the accumulation of detrimental aggregates down to less than 5 ng/cm2.[1] A recent surge of research has been conducted to create these surfaces in order to benefit the biological, nautical, mechanical, and medical fields.

Making Ultra-Low Fouling Surfaces

High surface energies cause adsorption because a contaminated surface will have a smaller difference between the surface and bulk coordination numbers. This drives the surface to reach a lower, more favored, energy state. A low energy surface would then be desired to prevent adsorption. It would be convenient if the desired surface was already low energy, but in many cases-such as metals-this is not the case.[2] One solution would be to layer the surface with a low surface energy polymer such as polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS). However, PDMS coating's hydrophobicity [3] causes any adsorbed particles to increase the surface energy, easing adhesion[4] and ultimately defeating the purpose. Oxidizing the PDMS surface does generate hydrophilic anti-fouling properties, but the low glass transition temperature allows for surface reconstruction via internal rearrangement: destroying hydrophilicity.[3]

In aqueous environments the alternative is to use high-energy hydrophilic coatings; whose chains become hydrated by the surrounding water and physically bar adsorbates. The most commonly used hydrophilic coating is poly ethylene glycol (PEG) due to its low cost.[5] On the other hand, PEG is highly susceptible to oxidation, which eventually destroys it’s hydrophilic properties.[5]

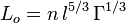

Hydrophilic surfaces are generally created one of two ways; the first being physisorption of an amphiphilic diblock co-polymer where the hydrophobic block adsorbs to the surface, leaving the hydrophilic block available for anti-fouling purposes. The second way is via surface initiated polymerization techniques which has been greatly influence by the development of controlled radical polymerization techniques such as Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization (ATRP). The physisorption results in mushroom regimes leaving much of the surface area of the hydrophilic polymer coiled up on itself while the grafting from approach results in highly ordered, tailorable, brush polymers. A film that is either too thick or too thin will adsorb particles onto the surface,[1] therefore film thickness becomes an important parameter in the synthesis of ultra-low fouling surfaces. Film thickness is determined by three factors that can be tailored individually to produce the desired thickness: one being the length of the polymer chains, the second being the grafting density and the last being the solvent concentration during polymerization.[1] The length of the chains is easily manipulated by varying the degree of polymerization by changing the ratio of initiator to monomer. The grafting density can be adjusted through varying the density of initiator on the surface. Film thickness can be theoretically calculated by the equation below;

where  is the thickness of the brush,

is the thickness of the brush,  is the number of segments in the polymer chain,

is the number of segments in the polymer chain,  is the average length of the grafted polymer chains, and

is the average length of the grafted polymer chains, and  is the grafting density.[6]

is the grafting density.[6]

If long polymer chains are used then a relatively sparse grafting density can be employed, but if the chains are short, a high grafting density is necessary. Furthermore, solvent concentration during polymerization affects both of these factors. Low concentration yields high-density short brush polymers, while high concentration results in low-density long polymers. Eventually, increasing solvent concentration creates a surface prone to fouling.[1]

Due to the eventual degradation of the polyethylene glycol (PEG) anti-fouling surfaces, new techniques employ zwitterionic polymers containing carboxybetaine or sulfobetaine due to their comparable hydration by water.[5] Zwitterions can be used to solve the fouling complications that arise from using PDMS, for PDMS is readily functionalized by zwitterionic polymers such as Poly(carboxybetaine methacrylate) (pCBMA).[3] This allows for a cheap, readily available substrate (PDMS) to be easily converted into an anti-fouling surface.

.png)

Testing Methodology

Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensors

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) sensors are thin film-refractometers that measure changes in refractive index occurring in the field of an electromagnetic wave supported by the optical structure of the sensor.[7] SPRs are widely used in order to determine the refractive index of ultra-low fouling surfaces, an important determinant in their anti-fouling capabilities. Protein adsorption can be measured using an SPR by detecting the change in refractive index arising from molecular adsorption at the sensor chip surface.[8] SPRs used in this type of experimentation have a detection limit of 0.3 ng/cm2 for nonspecific protein adsorption[9] allowing for the identification of a surface which is capable of achieving ultralow fouling (<5 ng/cm2).[7]

| Surface Coatings | Single protein adsorption | Adsorption in 100% human plasma | Adsorption in 100% human blood serum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Au[10] | - | 315 | - |

| pCB2-catechol2[8] | <0.3 | 8.9 ± 3.4 | 11.0 ± 5.0 |

| pSBMA300-catechol[1] | - | 1.6 ± 7.3 | 22.5 ± 7.5 |

| pCB[7] | <0.3 | 3.9 ± 0.8 | - |

| pCBAA[9] | <5 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | - |

| poly(MeOEGMA)[10] | - | 48 | - |

Table 1: Surfaces and their resistance to adsorption by single proteins, human plasma, and human blood serum measured in ng/cm2.

Ellipsometry

Ellipsometry, a form of sensitive polarized optical spectroscopy,[11] allows for the measurement of film refractive index (RI) and film thickness, both of which are important parameters for forming an ultra-low fouling surface.[1]

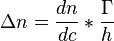

According to recent studies, film refractive index (RI) is the most important determinant in the nonfouling capabilities of a film.[1] In order to achieve ultra-low fouling a dry film needs to achieve a minimum polymer density, which is determined by RI, depending on the identity of the polymer coating.[1] The RI of a film can be increased by combining both long and polydisperse chains,[1] thus increasing the film’s nonfouling properties. From the measured change in RI the ability of an adsorbate molecule to bind to the surface of a material can be determined by

where  is the layer thickness,

is the layer thickness,  is the refractive index,

is the refractive index,  is the number of analyte molecules, and

is the number of analyte molecules, and  is the surface concentration.[7] Data collected on a zwitterionic pCBAA film suggested an RI range of 1.50 to 1.56 RIU is needed in order to achieve a nonspecific protein adsorption of <5 ng/cm2,[8] however data would vary depending on the identity of the film. This allows for a simple parameter to test the ultra-low fouling capabilities of polymer films.

is the surface concentration.[7] Data collected on a zwitterionic pCBAA film suggested an RI range of 1.50 to 1.56 RIU is needed in order to achieve a nonspecific protein adsorption of <5 ng/cm2,[8] however data would vary depending on the identity of the film. This allows for a simple parameter to test the ultra-low fouling capabilities of polymer films.

Another parameter for protein resistance is the film thickness. Also measured by ellipsometry, a film thickness too small or too large results in increased protein adsorption, indicating that some optimal value unique to the surface must be reached to achieve ultra-low fouling.[1]

Water Content

The amount of water present at the time of polymer attachment to the surface also has a high correlation to the packing density of the polymer film.[1] The effect of film thickness and RI on nonfouling properties can be better studied by varying the water content of the solution.[1] This is because increasing the amount of water increases the accessibility of the chain end due to the superhydrophilicity of zwitterionic materials and results in an increase in the polymerization rate, resulting in larger film thicknesses.[1] However, when the water concentration is too high, film thickness is decreased due to increased radical recombination of the polymer chain.[1]

Potential Applications

Anti-Microbial Surfaces

The anti-microbial properties of metal surfaces are of high interest to water sanitation. The metals produce an oligodynamic effect due to oxide formation and subsequent ion formation, making them biocidically active. This prevents contaminants from adhering to the surface. Coliform bacteria and E.coli content on metal surfaces have been shown to substantially decrease with time, indicating the ability of these surfaces to prevent biofouling and thus promote sanitation.[12] Of these metal surfaces, copper and zinc have been found to be most effective.[12] Polyurethane, polyethylene glycol, and other polymers have been shown to reduce external bacterial adhesion, which elicits applications of anti-microbial substances to the polymer and coatings industry. Sustainable alternatives like topographically modified cellulose are also of high interest due to recyclability and low cost.[13] Surfaces that are superhydrophobic are desirable for non-fouling behavior because an affinity for water correlates to an affinity for contaminants. Superhydrophobic xerogels made from silica colloids have been shown to reduce bacterial adhesion, specifically S. aureus and P. aeruginosa.[14] The non-fouling applications of these polymers and superhydrophobic coatings is of substantial importance to the field of medical devices.

Nautical Applications

Accumulation of marine organisms on vessels prevents efficient cruising speed from being obtained. Thus, ships affected by biofouling consume excess fuel and have increased costs.

Preventing biofouling

Traditionally, marine biofouling has been prevented through use of biocides: substances that deter or eliminate organisms upon contact. Yet most biocides are also harmful to humans, non-fouling marine organisms, and the general aquatic environment. Emerging regulations by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) have all but ceased application of biocides, causing a rush to research environmentally friendly ultra-low fouling materials.

Heavy Metal Paints

Toxic copper, iron, and zinc oxide pigments are mixed with rosin derivative binders to produce both water-soluble matrix paints, which are adhered to surfaces with bituminous-based primers. These have many disadvantages though, such as poor mechanical strength and sensitivity to oxidation. Thus, soluble matrix paints can only remain functional for a 12–15 month period, and are unsuitable for slow vessels. In contrast, insoluble matrix paints must use higher molecular weight binders: acrylics, vinyls, chlorinated rubbers, etc. and maintain stronger resistance to oxidation.[15] With better mechanical strength comes a higher biocide capacity, but also prevents consistent release of the biocide, resulting in a functional duration variating between 12 and 24 months. The chemical pigment form of these heavy metals often dissolves by the following mechanism:

Although only Copper(II) Oxide is shown, it can be analogized to other heavy metal oxides in this specific case. The most effective metallic variation utilized is tributyltin (TBT) water-soluble self-polishing paint, whose effectiveness in 1999 was estimated to save close to $US 2400 million and coat 70% of commercial ships:

However TBT, copper, zinc, and all other heavy metal coatings have been outlawed by the IMO.[15]

PDMS and derivatives

PDMS coatings are non-biocidal, leaving the ocean species unharmed. The basis of these elastomers is fouling-release: the prevention of organic substrate adhesion. This is accomplished due to the non-polarity, and more importantly low surface energy of PDMS. Consequently, the mechanical strength is weak, limiting efficiency and increasing dry-dock time. As a countermeasure, PDMS elastomers often are reinforced by carbon nanotubes and sepiolite mineral.[16] Fouling-release properties have also been reportedly improved via attachment of quaternary ammonium salts to the polymer backbone. Further research is currently underway to improve the effects of PDMS and its derivatives.

Mechanical Applications

Alloys of nickel and copper have also been shown to resist corrosion and pitting, which is of interest in piping systems for mechanical application, specifically in the offshore oil industry. A higher percentage of copper in these alloys (90/10 and 70/30) correlates to a higher resistance to biofouling and corrosion fouling. Other mechanical applications of these alloys include netting and cages for fish farming, hydraulic brake systems, piping for cooling systems, and components of flash distillation plants for desalination. [17]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Brault, Norman; Harihara Sundaram, Yuting Li, Chun-Jen Huang, Qiuming Yu, , and Shaoyi Jiang (2012). "Dry Film Refractive Index as an Important Parameter for Ultra-Low Fouling Surface Coatings". Biomacromolecules 13 (3): 589–593. doi:10.1021/bm3001217.

- ↑ Bondi, A. (1953). "The Spreading of Liquid Metals on Solid Surfaces. Surface Chemistry of High-Energy Surfaces.". Chemical Reviews 52: 417–458. doi:10.1021/cr60162a002.

- 1 2 3 Keefe, Andrew; Norman D. Brault; Shaoyi Jiang (2012). "Suppressing Surface Reconstruction of Superhydrophobic PDMS Using a Superhydrophilic Zwitterioinic Polymer". Biomacromolecules 13: 1683–1687. doi:10.1021/bm300399s.

- ↑ Wynne, K; G. Swain; R. Fox et al. (2000). Biofouling 16: 277–288. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 3 Qingsheng, Liu; Anuradha Singh; Lingyun Liu (2013). "Amino Acid-Based Zwitterionic Poly(serine methacrylate) as an Antifouling Material". Biomacromolecules 14: 226–231. doi:10.1021/bm301646y.

- ↑ Butt, Hans-Jϋrgen (2006). Physics and Chemistry of Interfaces. Weinhim: WILEY-VCH Verlag GimgH & Co. KGaA. p. 114. ISBN 9783527406296.

- 1 2 3 4 Homola, Jiří (2008). "Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensors for Detection of Chemical and Biological Species". Chemical Reviews 108 (2): 462–493. doi:10.1021/cr068107d. PMID 18229953.

- 1 2 3 Huang, Chun-Jen; Yuting Li; Shaoyi Jiang (2012). "Zwitterionic Polymer-Based Platform with Two-Layer Architecture for Ultra Low Fouling and High Protein Loading". Anal. Chem 84 (7): 3440–3445. doi:10.1021/ac3003769.

- 1 2 Gao, Changlu; Guozhu Li; Hong Xue; Wei Yang; Fengbao Zhang; Shaoyi Jiang; LTD ELSEVIER SCI (2010). "Functionalizable and Ultra-low Fouling Zwitterionic Surfaces Via Adhesive Mussel Mimetic Linkages". Biomaterials 31 (7): 1486–1492. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.025.

- 1 2 Riedel, Tomáš; Zuzana Riedelová-Reicheltová; Pavel Májek; César Rodriguez-Emmenegger; Milan Houska; Jan Dyr; Eduard Brynda (2013). "Complete Identification of Proteins Responsible for Human Blood Plasma Fouling on Poly(ethylene Glycol)-Based Surfaces". Langmuir 29 (10): 3388–3397. doi:10.1021/la304886r.

- ↑ Oates, T. W; H Wormeester, H Arwin, and LTD PERGAMON-ELSEVIER SCIENCE (2011). "Characterization of Plasmonic Effects in Thin Films and Metamaterials Using Spectroscopic Ellipsometry". Progress in Surface Science 86 (11-12): 328–376. doi:10.1016/j.progsurf.2011.08.004.

- 1 2 Varkey, A. J. (18 December 2010). "Antibacterial properties of some metals and alloys in combating coliforms in contaminated water". Scientific Research and Essays 5 (24): 3834–3839.

- ↑ Balu, Balamurali; Victor Breedveld; Dennis W. Hess (10 January 2008). "Fabrication of "Roll-off" and "Sticky" Superhydrophobic Cellulose Surfaces via Plasma Processing". Langmuir 24 (9): 4785–4790. doi:10.1021/la703766c.

- ↑ J. Privett, Benjamin; Jonghae Youn; Sung A. Hong; Jiyeon Lee; Junhee Han; Jae Ho Shin; Mark H. Schoenfisch (30 June 2011). "Antibacterial Fluorinated Silica Colloid Superhydrophobic Surfaces". Langmuir 27: 9597–9601. doi:10.1021/la201801e.

- 1 2 Almeida, Elisabete; Diamantino, de Sousa (2 April 2007). "Marine paints: The particular case of antifouling paints, Progress in Organic Coatings". Science Direct 59 (1): 2–20. doi:10.1016/j.porgcoat.2007.01.017.

- ↑ Turchyn, Windy. "Non-toxic Polymer Coatings for Fouling-Resistant Marine Surfaces" (PDF). www.chemistry.illinois.edu. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ↑ Powell, C.A. "Copper-Nickel for Seawater Corrosion Resistance and Antifouling - A State of the Art Review". Retrieved June 5, 2013.