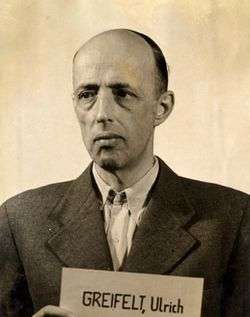

Ulrich Greifelt

Ulrich Heinrich Emil Richard Greifelt (8 December 1896 in Berlin – 6 February 1949 in Landsberg Prison) was an SS-Obergruppenführer, lieutenant general of police, and convicted war criminal. He was found guilty of war crimes at the RuSHA trial at Nuremberg, sentenced to life imprisonment, and died in Landsberg Prison.

Biography

Greifelt was born in Berlin in 1896, the son of a pharmacist. He joined the German army in 1914 and fought in the First World War.[1] After the war, he retired from the army with the rank of Oberleutnant.[2] Subsequently, he was a member of the Freikorps.[1] During the Weimar Republic, Greifelt worked as an economist at a Berlin joint-stock company until he was laid off in 1932 due to the difficult economic situation in Germany.[2]

After the Machtergreifung, Greifelt joined the Nazi Party in April 1933 (member no. 1,667,407) and the SS in June 1933 (member no. 72,909).[3] As of August 1933, Greifelt was a speaker on the Persönlicher Stab Reichsführer-SS. From early March to mid-June 1934, Greifelt was business leader for the chief of staff of SS-Oberabschnitts Mitte/Elbe, and then by mid-January 1935, chief of staff of SS-Oberabschnitt Rhein/Rhein-Westmark/Westmark. He then headed the Central Registry of the SS-Hauptamt.[3]

After the beginning of the Second World War, Greifelt was appointed Chief of Staff of RKFDV (Reichskommissar für die Festigung deutschen Volkstums; Reich Commissioner for the Consolidation of German Nationhood) in October 1939. He was instrumental in the "planning and implementation of population relocation in the context of Generalplan Ost".[3] In the SS, Greifelt rose quickly through the ranks, reaching Gruppenführer (major general) by 1941. He ultimately reached the rank of SS-Obergruppenführer und General der Polizei on 30 January 1944.

In February 1942, whilst serving on Heinrich Himmler's staff, Greifelt wrote a directive for dealing with children. According to what this laid out the Polish government had been responsible for seizing ethnic German children and placing them in orphanages and it was the duty of the Nazis to reclaim these children. He continued that those who "looked" German should be taken from orphanages, taken for examination at the SS-Rasse- und Siedlungshauptamt before underoging extensive psychological study. Those that were found to be of desirable racial stock were to be sent to German boarding schools and subsequently made available for adoption by the families of SS members, with their Polish origin to be concealed from any prospective parents.[4]

After the war of World War II, Greifelt was arrested in May 1945. Greifelt was sentenced to life imprisonment at the RuSHA trial on 10 March 1948. He had been found guilty as the person mainly responsible for the expulsion of people from Slovenia, Alsace, Lorraine and Luxembourg. He died in custody in the prison for war criminals in Landsberg.[5][6] Greifelt argued in his defence that he had the welfare of the people whom he expelled at heart and wanted to help them to find "the consolidation of their existence and thereby of their Germanism."[7] His claims were rejected however and he was sentenced under recently passed genocide legislation.[8]

Awards

- Iron Cross (1914), 1st and 2nd Class

- War Merit Cross (1939), 2nd and 1st Class with Swords

- Sword of Honour of the Reichsführer-SS

- SS-Ehrenring (SS Honour Ring)

References

- 1 2 Heinz Höhne. Der Orden unter dem Totenkopf - Die Geschichte der SS, Augsburg 1998, p. 283

- 1 2 Bastian Hein. Elite für Volk und Führer? Die Allgemeine SS und ihre Mitglieder 1925-1945, Oldenbourg, München 2012, p. 75

- 1 2 3 Angelika Ebbinghaus and Karl Heinz Roth. Kurzbiografien zum Ärzteprozess. In: Klaus Dörner (Hrsg.): Der Nürnberger Ärzteprozeß 1946/47. Wortprotokolle, Anklage- und Verteidigungsmaterial, Quellen zum Umfeld., München 2000, p. 92

- ↑ Catrine Clay & Michael Leapman, Master Race: The Lebensborn Experiment in Nazi Germany, Coronet Books, 1995, pp. 94-96

- ↑ Ernst Klee. Das Personenlexikon zum Dritten Reich, Frankfurt am Main 2007, p. 198

- ↑ This article contains a translation of the corresponding article in the German Wikipedia

- ↑ Clay & Leapman, Master Race, p. 173

- ↑ Clay & Leapman, Master Race, p. 175

|