Ulmus rubra

| Ulmus rubra | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mature cultivated slippery elm (Ulmus rubra) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Ulmaceae |

| Genus: | Ulmus |

| Species: | U. rubra |

| Binomial name | |

| Ulmus rubra Muhl.[1] | |

| |

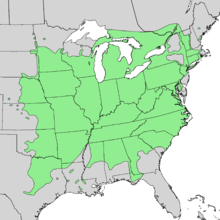

| Natural range of Ulmus rubra | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Ulmus rubra, the slippery elm, is a species of elm native to eastern North America, ranging from southeast North Dakota, east to Maine and southern Quebec, south to northernmost Florida, and west to eastern Texas, where it thrives in moist uplands, although it will also grow in dry, intermediate soils.[2]

Other common names include red elm, gray elm, soft elm, moose elm, and Indian elm. The tree was first named as part of Ulmus americana in 1753,[3] but identified as a separate species, Ulmus rubra, in 1793 by Pennsylvania botanist Gotthilf Muhlenberg. The slightly later name U. fulva, published by French botanist André Michaux in 1803,[4] is still widely used in dietary-supplement and alternative-medicine information.

The species superficially resembles American elm U. americana, but is more closely related to the European wych elm U. glabra, which has a very similar flower structure, though lacks the pubescence over the seed.[5] U. rubra was introduced to Europe in 1830.[3]

Description

Ulmus rubra is a medium-sized deciduous tree with a spreading head of branches,[6] commonly growing to 12–19 m (40–60 feet), very occasionally < 30 m (100 feet) in height. Its heartwood is reddish-brown, giving the tree its alternative common name 'red elm'. The species is chiefly distinguished from American elm by its downy twigs, red hairy buds, and slimy red inner bark. The broad oblong to obovate leaves are 10–20 cm (4–8 in) long, rough above but velvety below, with coarse double-serrate margins, acuminate apices and oblique bases; the petioles are 6–12mm long.[7] The leaves are often red tinged on emergence, turning dark green by summer, and then a dull yellow in the fall;[8] The perfect, apetalous, wind-pollinated flowers are produced before the leaves in early spring, usually in tight, short-stalked, clusters of 10–20. The reddish-brown fruit is an oval winged samara, orbicular to obovate, slightly notched at the top, 12–18 mm (1/2–3/4 in) long, the single, central seed coated with red-brown hairs, naked elsewhere.[7]

-

Asymmetrical leaf of Ulmus rubra

-

Mature bark of Ulmus rubra

Pests and diseases

The tree is reputedly less susceptible to Dutch elm disease than other species of American elms,[9] but is severely damaged by the elm leaf beetle (Xanthogaleruca luteola).[10]

Cultivation

The species has not been planted for ornament in its native country. Introduced to Europe and Australasia, it has never thrived in the UK; Elwes & Henry knew of not one good specimen,[5] and the last tree planted at Kew attained a height of only 12 m (38 ft) in 60 years.[7]

Notable trees

The USA National Champion, measuring 38 m high in 2011, grows in Daviess County, Indiana.[11] Another tall specimen grows in the Bronx, New York City, at 710 West 246th Street, measuring 31 m (100 feet) high in 2002.[12] In the UK, there is no designated TROBI champion, however several mature trees survive in Brighton (see Accessions).

Cultivars

There are no known cultivars, however the hybrid U. rubra × U. pumila cultivar 'Lincoln' is occasionally listed as Ulmus rubra 'Lincoln' in error.

Hybrids and hybrid cultivars

In the central United States, native Ulmus rubra hybridizes in the wild with the Siberian elm (U. pumila),[13] which was introduced in the early 20th century and which has spread widely since then, prompting conservation concerns for the former species.[14] U. rubra had limited success as a hybrid parent in the 1960s, resulting in the cultivars 'Coolshade', 'Lincoln', 'Rosehill', and probably 'Willis'.[15] In later years, it was also used in the Wisconsin elm breeding program to produce 'Repura' and 'Revera' [16] although neither is known to have been released to commerce.

Etymology

The specific epithet rubra (red) alludes to the tree's reddish wood, whilst the common name "slippery elm" alludes to the mucilaginous inner bark.

Uses

Medicinal

Ulmus rubra has various traditional medicinal uses. The mucilagenous inner bark of the tree has long been used as a demulcent, and is still produced commercially for this purpose in the United States with approval for sale as an over-the-counter demulcent by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.[17] Sometimes leaves are dried and ground into a powder, then made into a tea. Both Ulmus rubra gruel and tea may help to soothe the digestive tract.[18] It is however not recommended for women during pregnancy.[19] Slippery elm may decrease the absorption of prescription medications.[18]

Timber

The timber is not of much importance commercially, and is not found anywhere in great quantity.[5] Macoun considered it more durable than that of the other elms,[20] and better suited for railway ties, fence-posts, and rails, while Pinchot recommended planting it in the Mississippi valley, as it grows fast in youth, and could be utilized for fence-posts when quite young, since the sapwood, if thoroughly dried, is quite as durable as the heartwood.[21] The wood is also used for the hubs of wagon wheels, as it is very shock resistant owing to the interlocking grain.[22] The wood, as 'red elm', is sometimes used to make bows for archery. The yoke of the Liberty Bell, a symbol of the independence of the United States, was made from slippery elm.

Baseball

Though now outmoded, slippery elm tablets were chewed by spitball pitchers to enhance the effectiveness of the saliva applied to make the pitched baseball curve.[23]

Miscellaneous

The tree's fibrous inner bark produces a strong and durable fiber that can be spun into thread, twine, or rope[22] useful for bow strings, ropes, jewellery, clothing, snowshoe bindings, woven mats, and even some musical instruments. Once cured, the wood is also excellent for starting fires with the bow-drill method, as it grinds into a very fine flammable powder under friction.

Accessions

- North America

- Arnold Arboretum. Acc. nos. 737–88, 738–88, both of unrecorded provenance.

- Bernheim Arboretum and Research Forest , Clermont, Kentucky. No details available.

- Brenton Arboretum, Dallas Center, Iowa. No details available.

- Chicago Botanic Garden, Glencoe, Illinois. 1 tree, no other details available.

- Dominion Arboretum, Ottawa, Canada. No acc. details available.

- Longwood Gardens. Acc. no. L–3002, of unrecorded provenance.

- Nebraska Statewide Arboretum. No details available.

- Smith College. Acc. no. 8119PA.

- U S National Arboretum , Washington, D.C., USA. Acc. no. 77501.

- Europe

- Brighton & Hove City Council, NCCPG elm collection : Carden Park, Hollingdean (1 tree); Malthouse Car Park, Kemp Town (1 tree).

- Grange Farm Arboretum, Sutton St James, Spalding, Lincolnshire, UK. Acc. no. 522

- Hortus Botanicus Nationalis, Salaspils, Latvia. Acc. nos. 18168, 18169, 18170.

- Linnaean Gardens of Uppsala, Sweden. As U. fulva. Acc. no. 1955–1052.

- Royal Botanic Gardens Wakehurst Place. Acc. no. 1973–21050.

- Thenford House arboretum, Northamptonshire, UK. No details available.

- University of Copenhagen Botanic Garden. No details available.

- Australasia

- Eastwoodhill Arboretum , Gisborne, New Zealand. 1 tree, no details available.

References

- ↑ "Ulmus rubra information from NPGS/GRIN". www.ars-grin.gov. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- ↑ "Ulmus rubra Muhl". Northeastern Area State & Private Forestry.

- 1 2 J., White; D., More (2003). "Trees of Britain & Northern Europe". Cassell, London. ISBN 0-304-36192-5.

- ↑ Michaux, A. (1803). Flora Boreali-Americana ("The Flora of North America")

- 1 2 3 Elwes, H. J. & Henry, A. (1913). The Trees of Great Britain & Ireland. Vol. VII. 1862-4 (as U. fulva). Republished 2004 Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9781108069380

- ↑ Hillier & Sons. (1990). Hillier's Manual of Trees & Shrubs, 5th ed.. David & Charles, Newton Abbot, UK

- 1 2 3 Bean, W. J. (1970). Trees & Shrubs Hardy in the British Isles, 8th ed., p. 656. (2nd impression 1976) John Murray, London. ISBN 9780719517907

- ↑ Missouri Botanical Garden, Ulmus rubra

- ↑ "Ulmus rubra". Illinois State Museum.

- ↑ http://www.sunshinenursery.com/survey.htm

- ↑ American Forests. (2012). The 2012 National Register of Big Trees.

- ↑ Barnard, E. S. (2002) New York city trees. Columbia University Press, New York. ISBN 0-231-12835-5

- ↑ Zalapa, J. E.; Brunet, J.; Guries, R. P. (2008). "Isolation and characterization of microsatellite markers for red elm (Ulmus rubra Muhl.) and cross-species amplification with Siberian elm (Ulmus pumila L.)". Molecular Ecology Resources 8 (1): 109–12. doi:10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01805.x. PMID 21585729.

- ↑ 'Conservation status of Red Elm (U. rubra) in the north-central United States', elm2013.ipp.cnr.it/downloads/book_of_abstracts.pdfCached p.33-35

- ↑ Green, P S (24 July 1964). "Registration of cultivar names in Ulmus" (PDF). Arnoldia 24 (6–8): 41–46. hair space character in

|first=at position 2 (help) - ↑ Santamour, Frank S; Susan E Bentz (May 1995). "Updated checklist of elm (Ulmus) cultivars for use in North America". Journal of Arboriculture 21 (3): 122–131.

- ↑ Braun, Lesley; Cohen, Marc (2006). Herbs and Natural Supplements: An Evidence-Based Guide (2nd ed.). Churchill Livingstone. p. 586. ISBN 978-0-7295-3796-4. , quote:"Although Slippery Elm has not been scientifically investigated, the FDA has approved it as a safe demulcent substance."

- 1 2 "Bile reflux: Alternative medicine - MayoClinic.com". www.mayoclinic.com. Retrieved 2010-02-03.

- ↑ Pagano, John OA. Healing Psoriasis-The natural alternative. Wiley.

- ↑ Macoun, J. M. (1900). The Forest Wealth of Canada, p. 24. Canadian Commission for the Paris International Exhibition 1900.

- ↑ Pinchot, G. (1907). U S Forest Circular, no.85.

- 1 2 Werthner, William B. (1935). Some American Trees: An intimate study of native Ohio trees. New York: The Macmillan Company. pp. xviii + 398.

- ↑ "Spitball - BR Bullpen". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of a 1920 Encyclopedia Americana article about Ulmus rubra. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ulmus rubra. |

- USDA Plants profile for Ulmus rubra

- Dr. Duke's Databases: List of Chemicals in Ulmus rubra

- Ohio DNR.gov: Slippery Elm