United States Intelligence Community

Seal of the United States Intelligence Community | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | December 4, 1981 |

| Agency executive | |

The United States Intelligence Community (I.C.) is a federation of 16 separate United States government agencies that work separately and together to conduct intelligence activities considered necessary for the conduct of foreign relations and national security of the United States. Member organizations of the I.C. include intelligence agencies, military intelligence, and civilian intelligence and analysis offices within federal executive departments. The I.C. is headed by the Director of National Intelligence (DNI), who reports to the President of the United States.

Among their varied responsibilities, the members of the Community collect and produce foreign and domestic intelligence, contribute to military planning, and perform espionage. The I.C. was established by Executive Order 12333, signed on December 4, 1981, by U.S. President Ronald Reagan.[1]

The Washington Post reported in 2010 that there were 1,271 government organizations and 1,931 private companies in 10,000 locations in the United States that are working on counterterrorism, homeland security, and intelligence, and that the intelligence community as a whole includes 854,000 people holding top-secret clearances.[2] According to a 2008 study by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, private contractors make up 29% of the workforce in the U.S. intelligence community and cost the equivalent of 49% of their personnel budgets.[3]

Etymology

The term "Intelligence Community" was first used during Lt. Gen. Walter Bedell Smith's tenure as Director of Central Intelligence (1950–1953).[4]

History

Intelligence is information that agencies collect, analyze, and distribute in response to government leaders' questions and requirements. Intelligence is a broad term that entails:

Collection, analysis, and production of sensitive information to support national security leaders, including policymakers, military commanders, and Members of Congress. Safeguarding these processes and this information through counterintelligence activities. Execution of covert operations approved by the President. The IC strives to provide valuable insight on important issues by gathering raw intelligence, analyzing that data in context, and producing timely and relevant products for customers at all levels of national security—from the war-fighter on the ground to the President in Washington.[5]

Executive Order 12333 charged the IC with six primary objectives:[6]

- Collection of information needed by the President, the National Security Council, the Secretary of State, the Secretary of Defense, and other executive branch officials for the performance of their duties and responsibilities;

- Production and dissemination of intelligence;

- Collection of information concerning, and the conduct of activities to protect against, intelligence activities directed against the U.S., international terrorist and/or narcotics activities, and other hostile activities directed against the U.S. by foreign powers, organizations, persons and their agents;

- Special activities (defined as activities conducted in support of U.S. foreign policy objectives abroad which are planned and executed so that the "role of the United States Government is not apparent or acknowledged publicly", and functions in support of such activities, but which are not intended to influence United States political processes, public opinion, policies, or media and do not include diplomatic activities or the collection and production of intelligence or related support functions);

- Administrative and support activities within the United States and abroad necessary for the performance of authorized activities and

- Such other intelligence activities as the President may direct from time to time.

Organization

Members

The IC is headed by the The Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI), and made up of 16 members;[7]

- United States Air Force

- United States Army

- Central Intelligence Agency

- United States Coast Guard

- United States Department of Defense

- United States Department of Energy

- United States Department of Homeland Security

- United States Department of State

- United States Department of the Treasury

- United States Department of Justice

- Drug Enforcement Administration

- Office of National Security Intelligence

- Federal Bureau of Investigation

- Drug Enforcement Administration

- United States Marine Corps

- National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency

- National Reconnaissance Office

- National Security Agency

- United States Navy

Programs

The IC performs under two separate programs:

- The National Intelligence Program (NIP), formerly known as the National Foreign Intelligence Program as defined by the National Security Act of 1947 (as amended), "refers to all programs, projects, and activities of the intelligence community, as well as any other programs of the intelligence community designated jointly by the Director of National Intelligence (DNI) and the head of a United States department or agency or by the President. Such term does not include programs, projects, or activities of the military departments to acquire intelligence solely for the planning and conduct of tactical military operations by United States Armed Forces". Under the law, the DNI is responsible for directing and overseeing the NIP, though the ability to do so is limited (see the Organization structure and leadership section).

- The Military Intelligence Program (MIP) refers to the programs, projects, or activities of the military departments to acquire intelligence solely for the planning and conduct of tactical military operations by United States Armed Forces. The MIP is directed and controlled by the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence. In 2005 the Department of Defense combined the Joint Military Intelligence Program and the Tactical Intelligence and Related Activities program to form the MIP.

Since the definitions of the NIP and MIP overlap when they address military intelligence, assignment of intelligence activities to the NIP and MIP sometimes proves problematic.

Organizational structure and leadership

The overall organization of the IC is primarily governed by the National Security Act of 1947 (as amended) and Executive Order 12333. The statutory organizational relationships were substantially revised with the 2004 Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act (IRTPA) amendments to the 1947 National Security Act.

Though the IC characterizes itself as a federation of its member elements, its overall structure is better characterized as a confederation due to its lack of a well-defined, unified leadership and governance structure. Prior to 2004, the Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) was the head of the IC, in addition to being the director of the CIA. A major criticism of this arrangement was that the DCI had little or no actual authority over the budgetary authorities of the other IC agencies and therefore had limited influence over their operations.

Following the passage of IRTPA in 2004, the head of the IC is the Director of National Intelligence (DNI). The DNI exerts leadership of the IC primarily through statutory authorities under which he or she:

- controls the "National Intelligence Program" budget;

- establishes objectives, priorities, and guidance for the IC; and

- manages and directs the tasking of, collection, analysis, production, and dissemination of national intelligence by elements of the IC.

However, the DNI has no authority to direct and control any element of the IC except his own staff—the Office of the DNI—neither does the DNI have the authority to hire or fire personnel in the IC except those on his own staff. The member elements in the executive branch are directed and controlled by their respective department heads, all cabinet-level officials reporting to the President. By law, only the Director of the Central Intelligence Agency reports to the DNI.

In light of major intelligence failures in recent years that called into question how well Intelligence Community ensures U.S. national security, particularly those identified by the 9/11 Commission (National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States), and the "WMD Commission" (Commission on the Intelligence Capabilities of the United States Regarding Weapons of Mass Destruction), the authorities and powers of the DNI and the overall organizational structure of the IC have become subject of intense debate in the United States.

Interagency cooperation

Previously, interagency cooperation and the flow of information among the member agencies was hindered by policies that sought to limit the pooling of information out of privacy and security concerns. Attempts to modernize and facilitate interagency cooperation within the IC include technological, structural, procedural, and cultural dimensions. Examples include the Intellipedia wiki of encyclopedic security-related information; the creation of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, National Intelligence Centers, Program Manager Information Sharing Environment, and Information Sharing Council; legal and policy frameworks set by the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004, information sharing Executive Orders 13354 and Executive Order 13388, and the 2005 National Intelligence Strategy.

Budget

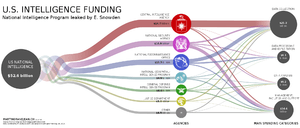

The U.S. intelligence budget (excluding the Military Intelligence Program) in fiscal year 2013 was appropriated as $52.7 billion, and reduced by the amount sequestered to $49.0 billion.[8] In fiscal year 2012 it peaked at $53.9 billion, according to a disclosure required under a recent law implementing recommendations of the 9/11 Commission.[9] The 2012 figure was up from $53.1 billion in 2010,[10] $49.8 billion in 2009,[11] $47.5 billion in 2008,[12] $43.5 billion in 2007,[13] and $40.9 billion in 2006.[14]

About 70 percent of the intelligence budget went to contractors for the procurement of technology and services (including analysis), according to the May 2007 chart from the ODNI. Intelligence spending has increased by a third over ten years ago, in inflation-adjusted dollars, according to the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments.

In a statement on the release of new declassified figures, DNI Mike McConnell said there would be no additional disclosures of classified budget information beyond the overall spending figure because "such disclosures could harm national security". How the money is divided among the 16 intelligence agencies and what it is spent on is classified. It includes salaries for about 100,000 people, multibillion-dollar satellite programs, aircraft, weapons, electronic sensors, intelligence analysis, spies, computers, and software.

On August 29, 2013 the Washington Post published the summary of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence's multivolume FY 2013 Congressional Budget Justification, the U.S. intelligence community's top-secret "black budget."[15][16][17] The IC's FY 2013 budget details, how the 16 spy agencies use the money and how it performs against the goals set by the president and Congress. Experts said that access to such details about U.S. spy programs is without precedent. Steven Aftergood, Federation of American Scientists, which provides analyses of national security issues stated that "It was a titanic struggle just to get the top-line budget number disclosed, and that has only been done consistently since 2007 … but a real grasp of the structure and operations of the intelligence bureaucracy has been totally beyond public reach. This kind of material, even on a historical basis, has simply not been available."[18] Access to budget details will enable an informed public debate on intelligence spending for the first time said the co-chair of the 9/11 Commission Lee H. Hamilton. He added that Americans should not be excluded from the budget process because the intelligence community has a profound impact on the life of ordinary Americans.[18]

Oversight

Intelligence Community Oversight duties are distributed to both the Executive and Legislative branches. Primary Executive oversight is performed by the President's Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, the Joint Intelligence Community Council, the Office of the Inspector General, and the Office of Management and Budget. Primary congressional oversight jurisdiction over the IC is assigned to two committees: the United States House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence and the United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence. The House Armed Services Committee and Senate Armed Services Committee draft bills to annually authorize the budgets of DoD intelligence activities, and both the House and Senate appropriations committees annually draft bills to appropriate the budgets of the IC. The Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs took a leading role in formulating the intelligence reform legislation in the 108th Congress.

See also

- Russian Intelligence Community

- Pakistani Intelligence Community (PIC)

- Australian Intelligence Community (AIC)

- National Virtual Translation Center

- UK-USA Security Agreement (UKUSA)

- Utah Data Center

- The Institute of World Politics

References

- ↑ "Executive Order 12333". Cia.gov. Retrieved 2013-01-23.

- ↑ Dana Priest and William M Arkin (19 July 2010). "A hidden world, growing beyond control". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Priest, Dana (2011). Top Secret America: The Rise of the New American Security State. Little, Brown and Company. p. 320. ISBN 0-316-18221-4.

- ↑ Michael Warner; Kenneth McDonald. "US Intelligence Community Reform Studies Since 1947" (PDF). CIA. p. 4. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- ↑ Rosenbach, Eric, and Aki J. Peritz (12 June 2009). "Confrontation or Collaboration? Congress and the Intelligence Community" (PDF). Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- ↑ Executive Order 12333 text

- ↑ http://www.dni.gov/index.php/intelligence-community/members-of-the-ic

- ↑ "DNI Releases Budget Figure for 2013 National Intelligence Program". Office of the Director of National Intelligence. 30 October 2013. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ↑ DNI Releases FY 2012 Appropriated Budget Figure. Dni.gov (2012-10-30). Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- ↑ "DNI Releases Budget Figure for 2010 National Intelligence Program" (PDF). Office of the Director of National Intelligence. 2010-10-28. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ↑ "DNI Releases Budget Figure for 2009 National Intelligence Program" (PDF). Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ↑ "DNI Releases Budget Figure for 2008 National Intelligence Program" (PDF). Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ↑ "DNI Releases Budget Figure for 2007 National Intelligence Program" (PDF). Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ↑ Hacket, John F. (2010-10-28). "FY2006 National Intelligence Program Budget, 10-28-10" (PDF). Office of the Director of National Intelligence. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ↑ Matt DeLong (29 August 2013). "Inside the 2013 U.S. intelligence 'black budget'". The Washington Post. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ↑ Matthews, Dylan (29 August 2013). "America's secret intelligence budget, in 11 (nay, 13) charts". The Washington Post. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ↑ DeLong, Matt (29 August 2013). "2013 U.S. intelligence budget: Additional resources". The Washington Post. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- 1 2 Barton Gellman and Greg Miller (29 August 2013). "U.S. spy network's successes, failures and objectives detailed in 'black budget' summary". The Washington Post. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

Further reading

- Richelson, Jeffrey T. (2012). The United States Intelligence Community (Sixth ed.). Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press. ISBN 9780813345123. OCLC 701015423.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to United States Intelligence Community. |

- Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports regarding U.S. Intelligence

- United States Intelligence Community website

- Top Secret America: A Washington Post Investigation

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||