USS New York (ACR-2)

| USS New York (ACR-2), off New York City during the victory fleet review, August 1898. | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: |

|

| Namesake: |

|

| Ordered: | 7 September 1888 |

| Awarded: | 28 August 1890 |

| Builder: | William Cramp & Sons, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Cost: | $2,985,000 (contract price of hull and machinery) |

| Laid down: | 30 September 1890 |

| Launched: | 2 December 1891 |

| Sponsored by: | Miss Helen Page |

| Commissioned: | 1 August 1893 |

| Decommissioned: | 29 April 1933 |

| Renamed: |

|

| Reclassified: | CA-2, 17 July 1920 |

| Struck: | 28 October 1938 |

| Identification: |

|

| Fate: | Scuttled 24 December 1941, Subic Bay, Philippines, wreck remains in place |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Type: | Armored cruiser |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: | |

| Beam: | 64 ft 10 in (19.76 m) |

| Draft: | 23 ft 3 in (7.09 m) (mean) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: | 2 × screws |

| Speed: | |

| Complement: | 53 officers, 422 enlisted, 40 Marines |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: | |

| General characteristics (1909)[1][2] | |

| Installed power: | 12 × Babcock & Wilcox boilers |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: | |

| General characteristics (1919)[2][3] | |

| Complement: | 73 officers, 511 enlisted, 64 Marines |

| Armament: |

|

USS New York (ACR-2/CA-2) was the second United States Navy armored cruiser so designated; the first was the ill-fated Maine, which was soon redesignated a second-class battleship. The fourth Navy ship to be named in honor of the state of New York, she was later renamed Saratoga and then Rochester. With six 8-inch guns, she was the most heavily armed cruiser in the US Navy when commissioned.[4][2]

She was laid down on 19 September 1890 by William Cramp and Sons, Philadelphia, launched on 2 December 1891, and sponsored by Miss Helen Clifford Page,[5] the daughter of J. Seaver Page, the secretary of the Union League Club of New York.[6] New York was commissioned 1 August 1893, Captain John Philip in command.[5]

Design and construction

Acquisition

In 1888, during the 50th Congress, 3.5 million dollars was authorized for the construction of New York.[6] She was designed by the Navy Department.[4] On 28 August 1890, the contract for her construction was awarded to William Cramp & Sons of Philadelphia.

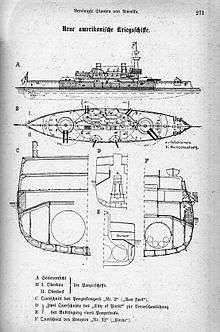

Armament

New York as built had a main armament of six 8 in (203 mm)/35 caliber Mark 3 and/or Mark 4 breech-loading rifles in two twin Mark 5 turrets fore and aft and two open single Mark 3 and/or Mark 4 mounts on the sides.[7] Secondary armament was twelve 4 in (102 mm)/40 caliber rapid fire (RF) guns in sponsons along the sides, along with eight 6-pounder (57 mm (2.2 in)) Driggs-Schroeder RF guns, four 1-pounder (37 mm (1.5 in)) Driggs-Schroeder RF guns, and three 14 in (356 mm) torpedo tubes for Howell torpedoes.[2][4][8]

Armor

New York, as an armored cruiser, had good protection. The belt was 4 in (102 mm) thick and 9 ft (2.7 m) deep, of which 4 ft (1.2 m) was below the waterline. It was 186 ft (57 m) long, protecting only the machinery spaces.[2][8] The armored deck was 6 in (152 mm) thick on its sloped sides and 3 in (76 mm) in the flat middle amidships, but only 2 1⁄2 in (64 mm) at the ends.[2][8] The original gun turrets had up to 5 1⁄2 in (140 mm) of armor, on 10 in (254 mm) barbettes with 5 in (127 mm) protecting the ammunition hoists.[2][8] The open single 8-inch mounts on the sides were much less protected by 2 in (51 mm) partial barbettes, while the secondary gun sponsons had 4 in (102 mm). The conning tower was 7 1⁄2 in (191 mm) thick.[2][8] During construction, the builder reconfigured New York's boiler arrangement for tighter compartmentation.[8]

Comparison with foreign ships

New York was a fast armored cruiser with a powerful armament, but the belt armor was thin compared to the first generation of older, slow armored cruisers, which tended to have a thick but narrow-coverage (waterline) belt. The thin side armor was comparable to that of the groundbreaking French armored cruiser Dupuy de Lôme, but the French ship's armor covered a much greater area of the hull.[9][10] New York had a greater number of heavy guns than the French cruiser. The hull protection of both ships was superior to their main rival, the British Blake class, which were the largest cruisers at the time but had no side armor.[11] The British had switched from building armored cruisers to favor very large, first class protected cruisers, and stuck with this policy until after the Diadem class.

Engineering

Along with having competitive weapons and armor, New York was intended to be relatively fast at 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph), and achieved 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) on trials. This was achieved with four triple-expansion engines totaling 16,000 ihp (12,000 kW), two clutched in tandem on each of two shafts.[8] The forward engines could be disconnected to conserve fuel at an economical cruising speed. In the US Navy, only Brooklyn shared this feature, which proved something of a liability in the Battle of Santiago de Cuba when both ships were operating with the forward engines disconnected and did not have time to reconnect them, thus limiting their speed.[12] As built, eight coal-fired cylindrical boilers supplied 160 psi (1,100 kPa) steam to the engines.[2][8]

Refits

New York underwent an extensive refit in 1905-1909. Her main guns and turrets were replaced with four 8 in (203 mm)/45 caliber Mark 6 guns in new Mark 12 turrets.[13] The new turrets and barbettes had improved Krupp cemented armor, with up to 6 1⁄2 in (165 mm) on the turrets and 6 in (152 mm)-4 in (102 mm) on the barbettes.[2] The side 8-inch guns and torpedo tubes were removed. The secondary armament was replaced as well, with ten 5 in (127 mm)/50 caliber Mark 6 guns and eight 3 in (76 mm)/50 caliber guns. She also received twelve Babcock & Wilcox boilers and the funnels were extended to improve natural draft through the boilers.[2] A further refit during World War I removed two 5-inch and all of the 3-inch single-purpose guns, adding two 3 in (76 mm)/50 anti-aircraft guns. In 1927 her boilers were reduced to four with two funnels, leaving only 7,700 ihp (5,700 kW).[2][4]

Service

In July 1893 New York performed sea trials using the Five Fathom Bank light station and the North East End light station as markers, achieving 21.0 knots (38.9 km/h; 24.2 mph) with 17,401 ihp (12,976 kW) at a displacement of 8,480 tons; at the time she was said to be the fastest armored vessel in the world.[2][8][14] On 1 August 1893 New York was commissioned at Philadelphia, Captain John Philip in command.[5] After completion, she was accepted by the Navy and left Cramp shipyards on 6 September for the League Island Navy Yard to load stores.[15]

USS New York (ACR-2)

Assigned to the South Atlantic Squadron, New York departed New York Harbor on 27 December 1893 for Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Arriving at Taipu Beach in January 1894, she remained there until heading home on 23 March, via Nicaragua and the West Indies. Transferred to the North Atlantic Squadron in August, the cruiser returned to West Indian waters for winter exercises and was commended for her aid during a fire that threatened to destroy Port of Spain, Trinidad.[5]

Returning to New York, New York joined the European Squadron in 1895, and steamed to Kiel, where she represented the United States at the opening of the Kiel Canal. Rejoining the North Atlantic Squadron, she operated off Fort Monroe, Charleston, and New York through 1897.[5]

New York departed Fort Monroe on 17 January 1898 for Key West. After the declaration of the Spanish–American War in April, she steamed to Cuba and bombarded the defenses at Matanzas before joining other American ships at San Juan in May, seeking the Spanish squadron. Not finding them, they bombarded El Morro Castle at San Juan (12 May) before withdrawing. New York then became flagship of Admiral William T. Sampson's squadron, as the American commander planned the campaign against Santiago. However, New York was taking Admiral Sampson to a meeting with Major General William Shafter when the Spanish fleet made its breakout attempt, some of her engines were disconnected which reduced her speed, and she was only able to participate in the closing phases of the battle.[12][16][17] The Battle of Santiago de Cuba on 3 July resulted in complete destruction of the Spanish fleet.[5]

The cruiser sailed for New York on 14 August to receive a warrior's welcome. The next year, she cruised with various state naval militia units to Cuba, Bermuda, Honduras, and Venezuela, and conducted summer tactical operations off New England. On 17 October 1899, she departed New York for Central and South American trouble areas.[5]

New York was transferred to the Asiatic Fleet in 1901, sailing via Gibraltar, Port Said, and Singapore to Cavite, where she became flagship of the Asiatic Fleet. She steamed to Yokohama in July for the unveiling of the memorial to the Perry Expedition. In October, New York visited Samar and other Philippine islands as part of the campaign against insurgents. On 13 March 1902, she got underway for Hong Kong and other Chinese ports. In September, she visited Vladivostok, Russia, then stopped at Korea before returning to San Francisco in November. In 1903, New York transferred to the Pacific Squadron and cruised with it to Ampala, Honduras in February to protect American interests during turbulence there. Steaming via Magdalena Bay, Mexico, the cruiser returned to San Francisco, for a reception for President Theodore Roosevelt. In 1904, New York joined squadron cruises off Panama and Peru, then reported to Puget Sound in June where she became flagship of the Pacific Squadron. In September, she enforced the President's neutrality order during the Russo-Japanese War. New York was at Valparaíso, Chile from 21 December 1904 – 4 January 1905, then sailed to Boston and decommissioned on 31 March for modernization.[5]

Recommissioning on 15 May 1909, New York departed Boston on 25 June for Algiers and Naples, where she joined the Armored Cruiser Squadron on 10 July and sailed with it for home on the 23rd. Operating out of Atlantic and gulf ports for the next year, she went into fleet reserve on 31 December.[5]

In full commission again on 1 April 1910, New York steamed via Gibraltar, Port Said, and Singapore to join the Asiatic Fleet at Manila on 6 August. While stationed in Asiatic waters, she cruised among the Philippine Islands, and ports in China and Japan.[5]

She was renamed Saratoga on 16 February 1911, to make the name "New York" available for the battleship New York (BB-34).[5]

USS Saratoga (ACR-2)

The cruiser spent the next five years in the Far East. Steaming to Bremerton, Washington on 6 February 1916, Saratoga went into reduced commission with the Pacific Reserve Fleet.[5]

As the U.S. drew closer to participation in World War I, Saratoga commissioned in full on 23 April 1917, and joined the Pacific Patrol Force on 7 June. In September, Saratoga steamed to Mexico to counter enemy activity in the troubled country. At Ensenada, Saratoga intercepted and helped to capture a merchantman transporting 32 German agents and several Americans seeking to avoid the draft law.[5]

In November, she transited the Panama Canal, joining the Cruiser Force, Atlantic Fleet at Hampton Roads. Here, she was renamed Rochester on 1 December 1917, to free the name "Saratoga" for the new battlecruiser Saratoga (CC-3) (eventually the aircraft carrier CV-3).[5]

USS Rochester (ACR-2/CA-2)

After escorting a convoy to France, Rochester commenced target and defense instruction of armed guard crews, in Chesapeake Bay. In March 1918, she resumed escorting convoys and continued the duty through the end of the war, with Alfred Walton Hinds in command. On her third trip, with convoy HM-58, a U-boat torpedoed the British steamer Atlantian on 9 June. Rochester sped to her aid, but Atlantian sank within five minutes. Other ships closed in, but the submarine was not seen again.[5]

After the Armistice, Rochester served as a transport bringing troops home. In May 1919, she served as flagship of the destroyer squadron guarding the transatlantic flight of the Navy's Curtiss NC seaplanes. On 17 July 1920 she was redesignated with the hull number CA-2 (heavy cruiser) as part of a fleetwide redesignation plan.[18] In the early 1920s, she operated along the east coast.[5]

Early in 1923, Rochester got underway for Guantanamo Bay to begin another period of service off the coasts of Central and South America.[5]

In the summer of 1925, Rochester carried General John J. Pershing and other members of his commission to Arica, Chile to arbitrate the Tacna-Arica dispute and remained there for the rest of the year. In September 1926, she helped bring peace to turbulent Nicaragua and from time to time returned there in the late 1920s.[5]

After a quiet 1927, Rochester relieved the gunboat Tulsa at Corinto in 1928 as Expeditionary Forces directed efforts against bandits in the area. Disturbances boiled over in Haiti in 1929, and opposition to the government was strong; inasmuch as American lives were endangered, Rochester transported the 1st Marine Brigade to Port-au-Prince and Cap-Haïtien. In 1930, Rochester transported the five-man commission sent to investigate the situation. In March, she returned to the area to embark marines and transported them to the U.S. She aided Continental Oil tanker H. W. Bruce, damaged in a collision on 24 May.[5]

In 1931, an earthquake rocked Nicaragua. Rochester was the first relief ship to arrive on the scene and ferried refugees from the area. Bandits took advantage of the chaotic conditions and Rochester steamed to the area to counter their activities.[5]

Rochester departed Balboa on 25 February 1932 for service in the Pacific Fleet. She arrived Shanghai on 27 April, to join the fleet in the Yangtze River in June and remained there until steaming to Cavite, to decommission on 29 April 1933. She would remain moored at the Olongapo Shipyard at Subic Bay for the next eight years. Her name was struck from the Naval Vessel Register on 28 October 1938, and she was scuttled on 24 December 1941 to prevent her capture by the Japanese.[5][19]

Awards

- Sampson Medal

- Spanish Campaign Medal

- Philippine Campaign Medal

- Victory Medal with "ARMED GUARD" and "ESCORT" clasps

- Second Nicaraguan Campaign Medal

- Yangtze Service Medal

Dive site Rochester

Since being scuttled, Rochester has been transformed into an artificial reef. The growth of the tourism industry has expanded and Subic Bay has become an upcoming dive vacation location. Rochester has become one of the most dived shipwrecks in Asia, given her somewhat shallow depth (59–88 ft (18–27 m)), ease of access, and proximity to other wrecks and activities. The wreck can be dived by most confident divers.

Rochester was scuttled with a small charge that blew a hole in her bottom in 1941. This resulted in minimal damage and left the wreck relatively intact. However, from 11 July 1967 to 20 July 1967 Harbor Clearance Team Four and Yard Light Lift Craft Two attached to Harbor Clearance Unit One conducted demolition as the U.S. Navy decided to try to flatten the wreck. Large charges were used on the central hull and these resulted in extensive damage around the midsection. This lowered the wreck; enabling deep draft tankers to approach and moor to the POL buoy planned for Subic Bay (at the same time, Navy divers helped to clear more than 650 wrecks from Manila bay).

Basic Divers – Lower than average visibility (due to proximity to the Olongapo river mouth) and deeper water makes this site more suitable for divers who have gained experience beyond entry-level training. The top of the wreck lies in 17-22m depth, covered in soft and whip corals with many reef fish. Lying slightly deeper (~59 ft (18 m) deep)divers can examine the uppermost barrel of an 8 in (200 mm) primary gun. The 361 ft (110 m) length gives plenty of area to observe as corals, sponges and fish life that have had over 60 years to convert it into home. Scorpionfish are common around this wreck and divers are reminded that these fish are dangerous to touch.

Experienced Wreck Divers – More advanced divers can explore the propeller, conning tower and deck areas. There are some areas of relatively easy penetration, with open-spaces and sufficient height to stay clear of major silt deposits. These include the following. The mess deck (2nd deck down) has an interesting penetration 197 ft (60 m) with portholes above allowing light, but no exit. The boiler room can be explored within recreation diving limits. Due to the nature of the wreck, with low light/viz and the risk of silt disturbance; redundant gas supplies and guideline deployment training are recommended for penetrations.

Advanced/Technical Wreck Divers – Three divers have died exploring inside Rochester - which indicates significant hazards and the need for advanced technical wreck training. Divers with appropriate decompression and advanced/technical wreck penetration training can access the engine room, machinery spaces and lower decks. These are in excellent condition, with huge pipes, machinery and valve wheels. Spaces can be extremely confined, with many restrictions and high risk of silt-out. Penetration is generally made on twin tanks, whilst deploying a constant guideline to the exit. Both engine room entrances are posted with notices warning of the dangers to the untrained.

References

- ↑ "Ships' Data, U. S. Naval Vessels". US Navy Department. 1 January 1914. pp. 24–31. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Gardiner and Chesneau, p. 147

- ↑ "Ships' Data, U.S. Naval Vessels". US Navy Department. 1 July 1921. p. 50. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Bauer and Roberts, p. 133

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 "New York (ACR-2)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- 1 2 "Launch of the New York". The Illustrated American 9: 217–219. 19 December 1891.

- ↑ DiGiulian, Tony, 8"/35 and 8"/40 USN guns at NavWeaps.com

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Friedman, pp. 34-39, 465-466

- ↑ Gardiner and Chesneau, pp. 147, 303

- ↑ Jane's 1905–1906, p.119, p.161

- ↑ Gardiner and Chesneau, p. 66

- 1 2 USS Brooklyn at SpanAmWar.com

- ↑ DiGiulian, Tony, 8"/45 US Navy guns at Navweaps.com

- ↑ "Cruiser New York". The Scranton Republican (Scranton, Pennsylvania). 27 March 1893. p. 1. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ↑ "News of the Navy". The Sun (New York, NY). 7 September 1893. p. 9.

- ↑ Battle of Santiago de Cuba at SpanAmWar.com

- ↑ USS New York at SpanAmWar.com

- ↑ USS New York/Saratoga/Rochester at NavSource Naval History

- ↑ "USS Rochester CA-2 (USS New York, USS Saratoga, ACR-2)". Pacific Wrecks.com. 7 August 2015. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

Bibliography

- Alden, John D. American Steel Navy: A Photographic History of the U.S. Navy from the Introduction of the Steel Hull in 1883 to the Cruise of the Great White Fleet. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1989. ISBN 0-87021-248-6

- Bauer, K. Jack; Roberts, Stephen S. (1991). Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775–1990: Major Combatants. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-26202-0.

- Bennett, Tom (2010). Shipwrecks of the Philippines (E-book). Wales, UK: Happy Fish Publications. ISBN 9780951211489.

- Burr, Lawrence. US Cruisers 1883–1904: The Birth of the Steel Navy. Oxford : Osprey, 2008. ISBN 1-84603-267-9 OCLC 488657946

- Davis, Charles W. "Subic Bay: Travel & Diving Guide." Manila, Philippines, Encyclea Publications, 2007. ISBN 978-971-0321-18-6

- Friedman, Norman (1984). U.S. Cruisers: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-718-6.

- Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1860–1905. New York: Mayflower Books. ISBN 0-8317-0302-4.

- Jane's Fighting Ships 1905/6. Arco Publishing Company, Inc. (reprint) 1970.

- Munsey's Magazine Volume XXVI. October 1901, to March 1902. Page 880 (article with paragraph on the Driggs-Schroeder six pounder guns used on USS Olympia, USS Brooklyn, and USS New York)

- Musicant, Ivan. U.S. Armored Cruisers: A Design and Operational History. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1985. ISBN 0-87021-714-3

- Taylor, Michael J.H. (1990). Jane's Fighting Ships of World War I. Studio. ISBN 1-85170-378-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to USS New York (ACR-2). |

- USS New York (CA-2) photos at Naval History & Heritage Command

- Photo gallery of USS NEW YORK/SARATOGA/ROCHESTER (ACR/CA-2) at NavSource Naval History

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||