National Monument (United States)

A National Monument in the United States is a protected area that is similar to a National Park, but can be created from any land owned or controlled by the federal government by proclamation of the President of the United States.

National monuments can be managed by one of several federal agencies: the National Park Service, United States Forest Service, United States Fish and Wildlife Service, or the Bureau of Land Management. Historically, some national monuments were managed by the War Department.[1]

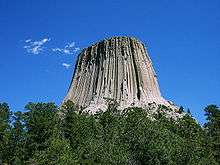

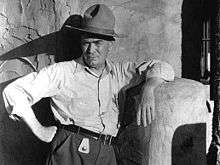

National monuments can be so designated through the power of the Antiquities Act of 1906. President Theodore Roosevelt used the act to declare Devils Tower in Wyoming as the first national monument.

History

The Antiquities Act of 1906 resulted from concerns about protecting mostly prehistoric Native American ruins and artifacts (collectively termed "antiquities") on federal lands in the American West. The Act authorized permits for legitimate archaeological investigations and penalties for taking or destroying antiquities without permission. Additionally, it authorized the President to proclaim "historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest" on federal lands as national monuments, "the limits of which in all cases shall be confined to the smallest area compatible with the proper care and management of the objects to be protected."[2]

The reference in the act to "objects of...scientific interest" enabled President Theodore Roosevelt to make a natural geological feature, Devils Tower in Wyoming, the first national monument three months later.[3] Among the next three monuments he proclaimed in 1906 was Petrified Forest in Arizona, another natural feature.

In 1908, Roosevelt used the act to proclaim more than 800,000 acres (3,200 km2) of the Grand Canyon as a national monument. May 24 1911, Pres. T. Roosevelt created the Colorado National Monument in Grand Junction.

In 1918, President Woodrow Wilson proclaimed Katmai National Monument in Alaska, comprising more than 1,000,000 acres (4,000 km2). Katmai was later enlarged to nearly 2,800,000 acres (11,000 km2) by subsequent Antiquities Act proclamations and for many years was the largest national park system unit. Petrified Forest, Grand Canyon, and Katmai were among the many national monuments later converted to national parks by Congress.[4][5]

In response to Roosevelt's declaration of the Grand Canyon monument, a putative mining claimant sued in federal court, claiming that Roosevelt had overstepped the Antiquities Act authority by protecting an entire canyon. In 1920, the United States Supreme Court ruled unanimously that the Grand Canyon was indeed "an object of historic or scientific interest" and could be protected by proclamation, setting a precedent for the use of the Antiquities Act to preserve large areas.[6] Federal courts have since rejected every challenge to the President's use of Antiquities Act preservation authority, ruling that the law gives the president exclusive discretion over the determination of the size and nature of the objects protected.

Substantial opposition did not materialize until 1943, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt proclaimed Jackson Hole National Monument in Wyoming. He did this to accept a donation of lands acquired by John D. Rockefeller, Jr., for addition to Grand Teton National Park after Congress had declined to authorize this park expansion. Roosevelt's proclamation unleashed a storm of criticism about use of the Antiquities Act to circumvent Congress. A bill abolishing Jackson Hole National Monument passed Congress but was vetoed by Roosevelt, and Congressional and court challenges to the proclamation authority were mounted. In 1950, Congress finally incorporated most of the monument into Grand Teton National Park, but the act doing so barred further use of the proclamation authority in Wyoming except for areas of 5,000 acres or less.

In 1949, for example, President Harry S. Truman proclaimed Effigy Mounds National Monument to accept a donation of the land from the state of Iowa, at the request of Iowa's delegation. On those rare occasions when the proclamation authority was used in seeming defiance of local and congressional sentiment, Congress again retaliated. Just before he left office in 1961, President Dwight D. Eisenhower proclaimed the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Monument after Congress had declined to act on related national historical park legislation. The chairman of the House Interior Committee, Wayne Aspinall of Colorado, responded by blocking action on subsequent C & O Canal Park bills to the end of that decade.

The most substantial use of the proclamation authority came in 1978, when President Jimmy Carter proclaimed 15 new national monuments in Alaska after Congress had adjourned without passing a major Alaska lands bill strongly opposed in that state. Congress passed a revised version of the bill in 1980 incorporating most of these national monuments into national parks and preserves, but the act also curtailed further use of the proclamation authority in Alaska.

The proclamation authority was not used again anywhere until 1996, when President Bill Clinton proclaimed the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in Utah. This action was widely unpopular in Utah,[7] and bills were introduced to further restrict the president's authority.[8] To date, none of them have been enacted. Most of the 16 national monuments created by President Clinton are managed not by the National Park Service, but by the Bureau of Land Management as part of the National Landscape Conservation System.

Presidents have used the Antiquities Act's proclamation authority not only to create new national monuments but to enlarge existing ones. For example, Franklin D. Roosevelt significantly enlarged Dinosaur National Monument in 1938. Lyndon B. Johnson added Ellis Island to Statue of Liberty National Monument in 1965, and Jimmy Carter made major additions to Glacier Bay and Katmai National Monuments in 1978.

List of National Monuments

See also

- List of U.S. National Forests

- List of areas in the National Park System of the United States (includes list of NPS-managed National Monuments)

- List of U.S. wilderness areas

- Wilderness preservation systems in the United States

References

- ↑ Glimpses of Our National Monuments. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1930.

- ↑ "American Antiquities Act". National Park Service. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- ↑ "Devils Tower First 50 Years" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- ↑ "PUBLIC LAW 85-358-MAR. 28, 1958" (PDF). Government Printing Office. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- ↑ "Records of the NPS". archives.gov. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- ↑ Cameron v. United States, 252 U.S. 450 (1920)

- ↑ Wieber, Audrey (October 12, 2014). "Locals Bitter Over Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Creation". MagicValley.com (Twin Falls Times-News). Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ↑ Lewis, Neil A. (October 8, 1997). "House Tweaks Clinton Over Creation of National Monuments". New York Times. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

External links

- National Monument Proclamations under the Antiquities Act (public domain text)

- Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports regarding National Monuments

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to National Monuments of the United States. |

| ||||||