United States Consumer Price Index

The U.S. Consumer Price Index (CPI) is a set of consumer price indices calculated by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). To be precise, the BLS routinely computes many different CPIs that are used for different purposes. Each is a time series measure of the price of consumer goods and services. The BLS publishes the CPI monthly.

Different indices computed by the BLS

The BLS started the statistic in 1919. It currently computes thousands of consumer price indices, beginning with monthly average prices for each of 8,018 category-area combinations (211 categories of consumption items in 38 urban geographical areas). They also track how much of each of these category area combinations is in the "market basket" consumed by different groups of people. Different published consumer price indices differ in the weights, including the target consumer group and how frequently the weights are updated. The weights for many indices are modified only in January of even-numbered years and are held constant for the next two years. However, weights for the chained CPI (C-CPI-U) are updated each month, so they more accurately track short term shifts in consumption patterns.[1]

CPI for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W)

The urban wage earner and clerical worker population consists of consumer units consisting of clerical workers, sales workers, craft workers, operative, service workers, or laborers. (Excluded from this population are professional, managerial, and technical workers; the self-employed; short-term workers; the unemployed; and retirees and others not in the labor force.[2]) More than one half of the consumer unit's income has to be earned from the above occupations, and at least one of the members must be employed for 37 weeks or more in an eligible occupation. The Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W) is a continuation of the historical index that was introduced after World War I for use in wage negotiation. As new uses were developed for the CPI, the need for a broader and more representative index became apparent. The Social Security Administration uses the CPI-W as the basis for its periodic COLA (Cost Of Living Adjustment).

CPI for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U)

The all-urban consumer population consists of all urban households in Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs) and in urban places of 2,500 inhabitants or more. Non-farm consumers living in rural areas within MSAs are included, but the index excludes rural consumers and the military and institutional population. The Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) introduced in 1978 is representative of the buying habits of approximately 80 percent of the non-institutional population of the United States, compared with 32 percent represented in the CPI-W. The methodology for producing the index is the same for both populations.

Core CPI

The core CPI index excludes goods with high price volatility, such as food and energy. This measure of core inflation systematically excludes food and energy prices because, historically, they have been highly volatile and non-systemic. More specifically, food and energy prices are widely thought to be subject to large changes that often fail to persist and do not represent relative price changes. In many instances, large movements in food and energy prices arise because of supply disruptions such as drought or OPEC-led cutbacks in production. This was introduced in the early 1970s when food and especially oil prices were quite volatile, and the Fed wanted an index that was less subject to short term shocks. However, on January 25, 2012, the Fed announced they would stop using the core CPI and rely instead on the Personal consumption expenditures price index.[3]

Chained CPI for All Urban Consumers (C-CPI-U)

This index applies to the same target population as the CPI-U, but the weights are updated each month. This allows the weights to evolve more gracefully with people's consumption patterns; for CPI-U, the weights are changed only in January of even-numbered years and are held constant for the next two years.[1]

CPI for the Elderly (CPI-E)

Since at least 1982, the BLS has also computed a consumer price index for the elderly to account for the fact that the consumption patterns of seniors are different from those of younger people. For the BLS, "elderly" means that the reference person or a spouse is at least 62 years of age; approximately 24 percent of all consumer units meet this definition. Individuals in this group consume roughly double the amount of medical care as all consumers in CPI-U or employees in CPI-W.[4]

In January of each year, Social Security recipients receive a cost of living adjustment (COLA) "to ensure that the purchasing power of Social Security and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits is not eroded by inflation. It is based on the percentage increase in the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W)".[5]

However, from December 1982 through December 2011, the all-items CPI-E rose at an annual average rate of 3.1 percent, compared with increases of 2.9 percent for both the CPI-U and CPI-W.[4] This suggests that the elderly have been losing purchasing power at the rate of roughly 0.2 (=3.1–2.9) percentage points per year.

In 2003 Hobijn and Lagakos estimated that the social security trust fund would run out of money in 40 years using CPI-W and in 35 years using CPI-E.[6]

Uses

- As an economic indicator. As the most widely used measure of inflation, the CPI is an indicator of the effectiveness of government fiscal and monetary policy. Especially for inflation targeting monetary policy by the Federal Reserve; however, the Federal Reserve System has recently begun favoring the Personal consumption expenditures price index (PCE) over the CPI as a measure of inflation. Business executives, labor leaders, and other private citizens also use the CPI as a guide in making economic decisions.

- As a deflator of other economic series. The CPI and its components are used to adjust other economic series for price change and to translate these series into inflation-free dollars.

- As a means for indexation (i.e. adjusting income payments). Over 2 million workers are covered by collective bargaining agreements which tie wages to the CPI. In the United States, the index affects the income of almost 80 million people as a result of statutory action: 47.8 million Social Security beneficiaries, about 4.1 million military and Federal Civil Service retirees and survivors, and about 22.4 million food stamp recipients. Changes in the CPI also affect the cost of lunches for the 26.7 million children who eat lunch at school. Some private firms and individuals use the CPI to keep rents, royalties, alimony payments and child support payments in line with changing prices. Since 1985, the CPI has been used to adjust the Federal income tax structure to prevent inflation-induced increases in taxes.

History

The Consumer Price Index was initiated during World War I, when rapid increases in prices, particularly in shipbuilding centers, made an index essential for calculating cost-of-living adjustments in wages. To provide appropriate weighting patterns for the index, it reflected the relative importance of goods and services purchased in 92 different industrial centers in 1917–1919. Periodic collection of prices was started, and in 1919 the Bureau of Labor Statistics began publication of separate indexes for 32 cities. Regular publication of a national index, the U.S. city average began in 1921, and indexes were estimated back to 1913 using records of food prices.

Because people's buying habits had changed substantially, a new study was made covering expenditures in the years 1934–1936, which provided the basis for a comprehensively revised index introduced in 1940. During World War II, when many commodities were scarce and goods were rationed, the index weights were adjusted temporarily to reflect these shortages. In 1951, the BLS again made interim adjustments, based on surveys of consumer expenditures in seven cities between 1947 and 1949, to reflect the most important effects of immediate postwar changes in buying patterns. The index was again revised in 1953 and 1964.

In 1978, the index was revised to reflect the spending patterns based upon the surveys of consumer expenditures conducted in 1972–1974. A new and expanded 85-area sample was selected based on the 1970 Census of Population. The Point-of-Purchase Survey (POPS) was also introduced. POPS eliminated reliance on outdated secondary sources for screening samples of establishments or outlets where prices are collected. A second, more broadly based CPI for All Urban Consumers, the CPI-U was also introduced. The CPI-U took into account the buying patterns of professional and salaried workers, part-time workers, the self-employed, the unemployed, and retired people, in addition to wage earners and clerical workers.[7]

The hidden change in prices of housing

In January 1983 housing prices were replaced with owners' equivalent of rent because rents are more stable. [8] Because house prices rose and fell more than rents during the housing bubble and crash, housing's effects on inflation and deflation are not reflected in the CPI.

Perceived errors in estimation

Perceived overestimation of inflation

In 1995, the Senate Finance Committee appointed a commission to study CPI's ability to estimate inflation. The CPI commission found in their study that the index overestimated the cost of living by a value between 0.8 to 1.6 percentage points.

If CPI overestimates inflation, then claims that real wages have fallen over time could be unfounded. An overestimation of only a few tenths of a percentage point per annum compounds dramatically over time. In the 1970s and 80s the federal government began indexing several transfers and taxes including social security (see below Uses of the CPI). The overestimation of CPI would imply that the increases in these taxes and transfers have been greater than necessary, meaning the government and taxpayers have overpaid for them.

The Commission concluded that more than half of the overestimation was due to slow adjustments in the index to new products or changes in product quality. At that time, the weights for indices like CPI-U and CPI-W were updated only once per decade; today, they are updated in January of even-numbered years. However, even with this more frequent updates, the CPI-U and CPI-W might still be excessively slow in responding to new technologies. For example, by 1996 there were over 47 million cellular phone users in the United States, but the weights for the CPI did not account for this new product until 1998. This new product lowered costs of communication when away from the home. The commission recommended that the BLS update weights more frequently to prevent upward bias in the index from a failure to properly account for the benefits of new products.

Additional upward biases were said to come from several other sources. Fixed weights do not accommodate consumer substitutions among commodities, such as buying more chicken when the price of beef increases.[9] Because the CPI assumes that people continue to buy beef, it would increase even if people are buying chicken instead. However, this is by design: the CPI measures the change in expenses required for people to maintain the same standard of living.[10] The Commission also found that 99% of all data were collected during the week, although an increasing amount of purchases happen during the weekend. Additional bias was said to stem from changes in retailing that were unaccounted for in the CPI.[11]

Perceived underestimation of inflation

Some critics believe however, that because of changes to the way that the CPI is calculated, and because energy and food price changes were excluded from the Federal Reserve's calculation of "core inflation", that inflation is being dramatically underestimated.[12][13] The second argument is unrelated to the CPI, except insofar as the calculation of CPI is modified in response to a perceived overstatement of inflation.

The Federal Reserve's policy of ignoring food and energy prices when making interest rate decisions is often confused with the Bureau of Labor Statistics' measurement of the CPI. The BLS publishes both a headline CPI which counts food and energy prices, and also a CPI for All Items Less Food and Energy, or "Core" CPI. None of the prominent legislated uses of the CPI excludes food and energy.[14] However, with regard to calculating inflation, the Federal Reserve no longer uses the CPI, preferring to use core PCE instead.

Some critics believe that changes in CPI calculation due to the Boskin Commission have led to dramatic cuts in inflation estimates. They believe that using pre-Boskin methods, which they also think are still used by most other countries, the current U.S. inflation is estimated to be around 7% per year. The BLS maintains that these beliefs are based on misunderstandings of the CPI. For example, the BLS has stated that changes made due to the introduction of the geometric mean formula to account for product substitution (one of the Boskin recommended changes) have lowered the measured rate of inflation by less than 0.3% per year, and the methods now used are commonly employed in the CPIs of developed nations.[15]

Method of calculation

The calculation of the CPI involves a hybrid methodology consisting of two stages:

In the first stage, elementary indices are created to show the price levels of very similar goods in the same area. For instance, there is an elementary index for "sports equipment in Seattle".[16] As of June 2007, there are 8,018 of these elementary indices [8,018 = 211 * 38, where 211 is the number of categories ("item strata") and 38 is the number of geographical areas considered].[17] All but a few of the elementary indices are based on geometric mean formulas.

In the second stage, the elementary indices are combined to create a number of aggregate indices, including the CPI. (The CPI is an aggregate of all 8,018 basic indices. BLS also computes other aggregates computed uses smaller subsets of the basic indices. For instance, there is an all-items index for Boston, and an all-areas index for electricity.)

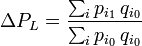

These aggregate indices (including the CPI) are calculated using a Laspeyres index computed as:

where:

is the relative change in price level,

is the relative change in price level,

is the price of each good

is the price of each good  in the first period,

in the first period,

is the quantity of each good

is the quantity of each good  in the first period,

in the first period,

is the price of each good

is the price of each good  in the second period.

in the second period.

Weights of the CPI

The weight (or quantities, to use the above terminology) of an item in the CPI is derived from the expenditure on that item as estimated by the Consumer Expenditure Survey. This survey provides data on the average expenditure on selected items, such as white bread, gasoline and so on, that were purchased by the index population during the survey period. In a fixed-weight index such as CPI-U, the implicit quantity of any item used in calculating the index remains the same from month to month.

A related concept is the relative importance of an item. The relative importance shows the share of total expenditure that would occur if quantities consumed were unaffected by changes in relative prices and actually remained constant. Although the implicit quantity weights remain fixed, the relative importance changes over time, reflecting average price changes. Items registering a greater than average price increase (or smaller decrease) become relatively more important.

Method evaluation

This two-stage method is relatively new. Before 1999, CPI used only Laspeyres indices, measures of the price changes in a fixed market basket of consumption goods and services of constant quantity and quality bought on average by urban consumers, either for all urban consumers (CPI-U) or for urban wage earners and clerical workers (CPI-W). It is argued that Laspeyres index systematically overstates inflation because it does not take into account changes in the quantities consumed that may occur as a response to price changes. The Laspeyres formula works under the assumption that consumers always buy the same amount of each good in the market basket, no matter what the price. The geometric mean price index formula used to calculate many of the elementary indices, in contrast, assumes that consumers will always spend the same amount of money on a good and shift the quantity they buy of that good based on the price. Critics argue that consumers standard of living has declined if price increases force them from preferred to less preferred goods. This logic suggests that the geometric mean price formula understates inflation.

See also

- Consumer Price Index

- Cost of Living

- Boskin Commission

- Stigler Commission

- Inflation

- Core inflation

- Bureau of Labor Statistics

- Producer Price Index

- GDP deflator

- Monetary Policy

- Hedonic regression

- Implicit price deflator (IPD)

- List of economics topics

References

- 1 2 "Frequently Asked Questions about the Chained Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (C-CPI-U)". Consumer Price Index. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved April 11, 2013.

For example, the CPI-U for the years 2004 and 2005 uses expenditure weights drawn from the 2001–2002 Consumer Expenditure Surveys.

- ↑ "Prices" (Section 14). Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2006

- ↑ Shulman, David (January 26, 2012). "Federal Reserve Abandons Core Consumer Price Index". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved April 12, 2013.

- 1 2 "Consumer Price Index for the Elderly". The Editor's Desk (Bureau of Labor Statistics). March 2, 2012.

- ↑ "Cost-Of-Living Adjustment (COLA) Information For 2013". Cost-Of-Living Adjustment. Social Security Administration. Retrieved April 11, 2013.

- ↑ Hobijn, Bart; Lagakos, David (May 2003). "Social Security and the Consumer Price Index for the Elderly". Current Issues in Economics and Finance (Federal Reserve Bank of New York) 9 (5): 1–6. Retrieved April 11, 2013.

- ↑ "17. The Consumer Price Index" (PDF). BLS Handbook of Methods. Bureau of Labor Statistics. June 0207. Retrieved April 12, 2013.

- ↑ U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. "How the CPI measures price change of Owners' equivalent of rent of primary residence (OER) and Rent of primary residence (Rent)".

- ↑ Lebergott, Stanley (1993). Pursuing Happiness: American Consumers in the Twentieth Century. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. See Fig. 9.1. ISBN 0-691-04322-1. The real price of chicken fell rather sharply relative to beef over the past several decades.

- ↑ http://www.bls.gov/cpi/cpiqa.htm#Question_3

- ↑ Boskin et al. (Winter 1998). "Consumer Prices, The Consumer Price Index, and the Cost of Living". Journal of Economic Perspectives 12 (1): 3–26. doi:10.1257/jep.12.1.3.

- ↑ The great inflation cover-up

- ↑ Waggoner, John (2004-11-26). "If you think inflation is on the move, time to protect portfolio". USA Today. Retrieved 2008-02-03.

- ↑ http://www.bls.gov/cpi/cpiqa.htm

- ↑ Addressing misconceptions about the Consumer Price Index

- ↑ Chapter 17, BLS handbook (06/2007 revision). Page 33.

- ↑ Chapter 17, BLS handbook (06/2007 revision, page 3).

Further reading

- Boskin, Michael J. (2008). "Consumer Price Indexes". In David R. Henderson (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Library of Economics and Liberty. ISBN 978-0865976658. OCLC 237794267.

External links

- U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, CPI Home Page

- US Inflation Calculator & CPI US Inflation Calculator based on CPI data (1913–current).

- US Inflation Rate Tables, Charts, Calculators CPI-U based inflation rate tables, charts, calculators, comparison with other countries and periods.

- Note on a New, Supplemental Index of Consumer Price Change (Introduction to C-CPI-U)

- Consumer Price Index Chart Series Historical CPI data charted against other major economic indicators

- An Introductory look at the Chained Consumer Price Index

- Chained Consumer Price Index Top Picks at BLS