Tudor architecture

The Tudor architectural style is the final development of Medieval architecture in England, during the Tudor period (1485–1603) and even beyond. It followed the Perpendicular style and, although superseded by Elizabethan architecture in domestic building of any pretensions to fashion, the Tudor style long retained its hold on English taste. Nevertheless, 'Tudor style' is an awkward style-designation, with its implied suggestions of continuity through the period of the Tudor dynasty and the misleading impression that there was a style break at the accession of Stuart James I in 1603.

The four-centered arch, now known as the Tudor arch, was a defining feature. Some of the most remarkable oriel windows belong to this period. Mouldings are more spread out and the foliage becomes more naturalistic. During the reigns of Henry VIII and Edward VI, many Italian artists arrived in England; their decorative features can be seen at Hampton Court, Layer Marney Tower, Sutton Place, and elsewhere. However, in the following reign of Elizabeth I, the influence of Northern Mannerism, mainly derived from books, was greater. Courtiers and other wealthy Elizabethans competed to built prodigy houses that proclaimed their status.

The Dissolution of the Monasteries redistributed large amounts of land to the wealthy, resulting in a secular building boom, as well as a source of stone.[1] The building of churches had already slowed somewhat before the English Reformation, after a great boom in the previous century, but was brought to a nearly complete stop by the Reformation. Civic and university buildings became steadily more numerous in the period, which saw general increasing prosperity. Brick was something of an exotic and expensive rarity at the beginning of the period, but during it became very widely used in many parts of England, even for modest buildings, gradually restricting traditional methods such as wood framed daub and wattle and half-timbering to the lower classes by the end of the period.

Typical features

Tudor style buildings have several features that separate them from Medieval and later 17th-century design.

Nobility, upper classes, and clerical

The early years

Prior to 1485, most wealthy and noble lived in homes that were not necessarily comfortable but built to withstand sieges. Castles and smaller manor houses often had moats, portcullises, and crenellations designed for archers to stand guard and pick off approaching enemies. If that failed enemy invaders, there were holes in the ceiling where soldiers would lie in wait to pour boiling oil or tar on top of the heads of attackers, and dungeons were so feared that, in England at least, the very mention of Pontefract Castle's vast underground chambers sent chills up the commoner's spine long after they fell into disuse, as evidenced by William Shakespeare, a commoner himself, mentioning its notorious reputation in the play Richard III in 1597.

However, with the arrival of gunpowder and cannons by the time of Henry VI, fortifications like castles became increasingly obsolete. The autumn of 1485 marked the ascension of Henry VII to the throne. In 1487, Henry Tudor passed laws against livery and maintenance, which checked the nobility's ability to raise armies independent of the crown, and raised taxes on the nobility through a trusted advisor, John Morton. In architecture, these laws opened the door to wealthy homes being built for material comfort and aesthethics rather than as imposing stone citadels. Though this period is better known for the luxuries and excesses of his son and granddaughter, it was under Henry VII that the transition from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance began. In the early part of his reign, Henry Tudor favored a site at Sheen as his primary residence that had hosted royalty intermittently going back to the time of Edward II, with the most recent edition as of 1496 being started by Henry V in 1414. The building was largely a wooden edifice with cloisters and several features of the Middle Ages, such as a grand central banqueting hall, and the Privy Chambers facing the river very much resembling a 15th-century castle.[2]

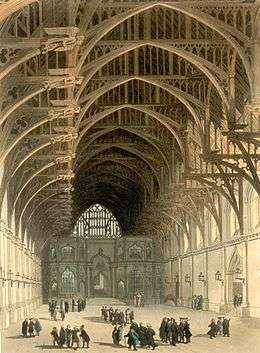

However, at Christmastide 1497 a horrific fire broke out in the king's private chambers, destroying a large portion of the palace: the Milanese ambassador,Raimondo Soncino, witnessed the blaze, and estimated the damage at 60,000 ducats, in modern money about $10,138,450, or approximately 7 million British pounds. The fire lasted three hours and tore through the rest of the palace, causing panic and hundreds to flee.[3] Hammerbeam roofs of the Middle Ages were a structural necessity as much as they were pretty architecture as they kept the heavy timbered roofs from caving in; they were the carpenter's equivalent of the stone vaulting found in Gothic cathedrals of the Middle Ages because as in famous examples, like Westminster Abbey, they allowed the architect greater ability to achieve higher heights with thinner walls and evenly distributed the lateral weight.[4] In as large a fire as described by Soncino the English oak beams of the great hall, a centerpiece of a royal Christmas, would have stood no chance of remaining upright and intact. They would have been engulfed in flames in the high temperatures well exceeding 270 °C. Much of the tapestry work of earlier ages was burnt to cinder, and losses included crown jewels and much of the royal wardrobe including a large amount of cloth of gold, at this time a luxury item only wearable by royalty and in the case of Sheen Palace it was a feature of the bedding.[5] Henry Tudor, his mother, Margaret Beaufort, his wife, Queen Elizabeth, and their children, Margaret, Mary, and the youngster Henry VIII were in residence at the time of the fire, with the king barely escaping the collapse of one of the hallways on top of him. Soncino reports all of this, and also states in his accounts that the king "does not attach much importance to this loss. He purposes to build the chapel all in stone, and much finer than before." [6]

Construction on the new palace began in 1498 as soon as the salvage of whatever remained could be managed. Henry named his creation Richmond Palace, in honor of the title he held before ascending to the throne and the title he inherited from his father: Earl of Richmond. Though the palace did not survive the English Civil War, fragments of the edifice still remain along the bank of the Thames as does Richmond Park, originally a royal hunting reserve that Henry Tudor and all members of the Tudors and early Stuarts used for their personal entertainment. Henry Tudor built a monstrously large and grand palace that became the center of royal life for many years to come. Drawings and descriptions of the palace survive as does the documentation of a 1970s excavation of the grounds, thus posterity has a fairly accurate idea of what the contents and features of the building were. Richmond Palace was largely a building of brick and white stone that was outfitted with the latest styles of the times, with geometric octagonal towers, pepper pot chimney caps, and ornate weathervanes made of brass.[7] Though it retained the layout of Sheen Palace new additions that would mark the Renaissance were to be found in this palace, for example, long galleries to display sculpture and portraiture, and a complete and utter lack of a keep: castles typically had enormous thick walls with an inner layer of building protected by an outer layer, as shown in surviving castles like Warwick Castle and York Castle, and had been that way since the Normans, as shown in the Tower of London, originally built during the time of William the Conqueror and downriver from Henry Tudor's palace. The windows were paneled, built to bring in more light than the tiny slit like windows of a castle, built for defense. From its earliest it had inner courtyards designed for leisure, with several portions built for the royal family overlooking a large green. It is known that Henry Tudor decorated his home with many gifts he accepted from Italian bankers in Venice, and the evidence survives in a 17th-century inventory taken of the palace that is now located in the British National Archives. The inventory also describes new tapestries he commissioned to replace the ones lost in the fire.

Henry VIII and later

Henry VII was succeeded by his second son, Henry VIII, a man of a very different character of his father: much taller than his father at 188 centimeters, bright red hair, and with a talent for spending money on whatever caught his fancy: it is known that in a courtyard of Hampton Court Palace he installed a fountain that spurted nothing but red wine.[8] During the reign of Henry VIII, architecture became a favourite pastime of the king, especially when it came to showing grandeur or flattering the ego of this larger than life king. Henry VIII spent an enormous amount of money on building new palaces and even some military installations all along the Southern coast of England and the border with Scotland, at the time a separate nation.

As time wore on, quadrangular, 'H' or 'E' shaped floor plans became more common, with the H shape coming to fruition during the reign of Henry VII's son and successor.[9] It was also fashionable for these larger buildings to incorporate 'devices', or riddles, designed into the building, which served to demonstrate the owner's wit and to delight visitors. Occasionally these were Catholic symbols, for example, subtle or not so subtle references to the trinity, seen in three-sided, triangular, or 'Y' shaped plans, designs or motifs.[10] Earlier clerical buildings would have had a cross shape so as to honor Christ, such as in Old St Paul's and the surviving York Cathedral, but as with all clerical buildings, this was a time of great upheaval catalyzed by Henry VIII's Reformation. Henry set himself up as head of the church and confiscated the lands, titles, and bluntly he nearly destroyed the entire physical footprint of the Roman Catholic Church in England. A part of his policy was the suppression of the

During this period the arrival of the chimney stack and enclosed hearths resulted in the decline of the great hall based around an open hearth that was typical of earlier Medieval architecture. Instead, fireplaces could now be placed upstairs and it became possible to have a second story that ran the whole length of the house.[11] Tudor chimney-pieces were made large and elaborate to draw attention to the owner's adoption of this new technology.[1] The jetty appeared, as a way to show off the modernity of having a complete, full-length upper floor.[1]

Buildings constructed by the wealthy had these common characteristics:

- An 'E' or 'H' shaped floor plan

- Brick and stone masonry, sometimes with half timbers earlier in the period

- Recycling of older medieval stone. Signs of hand riven stone masonry from earlier than 1505 consistent with Henry VIII's policy of plundering building materials from priories and abbeys. Especially common in country estates.

- Curvilinear gables, an influence taken from Dutch designs

- Large displays of glass in very large windows several feet long; glass was expensive so only the rich could afford numerous, large windows

- Depressed arches in clerical and aristocratic design, especially in the early-middle portion of the period

- Hammerbeam roofs still in use for great halls from Medieval period under Henry VII until 1603; were built more decoratively, often with geometric-patterned beams and corbels carved into beasts

- Classical accents such as round-headed arches over doors and alcoves, plus prominent balustrades from time of Henry VIII to Elizabeth I

- Large brick chimneys, often topped with narrow decorative chimney pots in the homes of the upper middle class and higher. Ordinary medieval village houses were often made much more pleasant to live in by the addition of brick fireplaces and chimneys, replacing an open heath.

- Wide, enormous stone fireplaces with very large hearths meant to accommodate larger scale entertaining; in aristocratic homes these often were customized with motifs from the family coat of arms. Cooking fireplaces would be found in lower sections of a stately home in a great kitchen and be large enough to fit a bed inside.

- Enormous ironwork for spit roasting located inside cooking fireplaces. In the homes of the upper class and nobility it was fashionable to show off wealth by being able to roast all manner of beasts weighing less than 500 grams on up to a full grown bull; in the case of royalty it would be seen as dishonor if the monarch's table could not provide equal to that of the Continental powers of France and Spain. Managing the flames would be the job of either a spit boy (Henry VII's reign) or later on a new invention where a turnspit dog ran on a treadmill (Elizabeth I's reign.)

- Long galleries

- Tapestries serving a triple purpose of keeping out chill, decorating the interior, and displaying wealth. In the wealthiest homes these may contain gold or silver thread.

- Gilt detailing inside and outside the home

- Geometric landscaping in the back of the home: large gardens and enclosed courtyards were a feature of the very wealthy. Fountains begin to appear in the reign of Henry VIII.

Commoner classes

.jpg)

The houses and buildings of ordinary people were typically timber framed. The frame was usually filled with wattle and daub but occasionally with brick.[1] These houses were also slower to adopt the latest trends, and the great hall continued to prevail.[11]

Smaller Tudor-style houses display the following characteristics:

- Simpler square or rectangular floor plans in market towns or cities

- Farmhouses retain a small fat 'H' shape and traces of late Medieval architecture; modification was less expensive than entirely rebuilding

- Steeply pitched roof, with thatching or tiles of slate or more rarely clay (London did not ban thatched roofs within the city until the 1660s)

- Cruck framing in use throughout the period

- Hammerbeam roofs retained for sake of utility (remained common in barns)

- Prominent cross gables

- Tall, narrow doors and windows

- Small diamond-shaped window panes, typically with lead casings to hold them together

- Dormer windows, late in the period

- Flagstone or dirt floors rather than all stone and wood

- Half-timbers make of oak, with wattle and daub walls painted white

- Brickwork in homes of gentry, especially Elizabethan. As with upper classes, conformed to a set size of 210–250 mm (8.3–9.8 in) × 100–120 mm (3.9–4.7 in) × 40–50 mm (1.6–2.0 in), bonded by mortar with a high lime content

- Jettied top floor to increase interior space;[12] very common in market town high streets and larger cities like London

- Extremely narrow to nonexistent space between buildings in towns

- Inglenook fireplaces. Open floor fireplaces were a feature during the time of Henry VII but had declined in use by the 1560s for all but the poor as the growing middle classes were becoming more able to build them into their homes. Fireplace would be approximately 138 cm (4.5 ft) wide × 91 cm (3 ft) tall × at least 100 cm (3.3 ft) deep. The largest fireplace – in the kitchen – had a hook nailed into the wall for hanging a cooking cauldron rather than the tripod of an open plan. Many chimneys were coated with lime or plaster inside to the misfortune of the owner: when heated these would decompose and thus the very first fire codes were implemented during the reign of Elizabeth I, as many lost their homes because of faulty installation.

- Oven not separated from apparatus used in fireplace, especially after the reign of Edward VI; middle-class homes had no use for such enormous ovens nor money to build them.

- More emphasis on wooden staircases in homes of the middle class and gentry

- Outhouses in the back of the home, especially beyond cities in market towns

- Little landscaping behind the home, but rather small herb gardens.

Examples of Tudor architecture

Church

In church architecture the principal examples are:

- King's College Chapel, Cambridge (1446–1515)

- St. George's Chapel, Windsor Castle (1475–1528)

- Henry VII Lady Chapel at Westminster Abbey (1503)

College

Tudor architecture remained popular for conservative college patrons, even after it had been replaced in domestic building. Portions of the additions to the various colleges of the University of Oxford and the University of Cambridge were still carried out in the Tudor style, overlapping with the first stirrings of the Gothic Revival.

There are also examples of Tudor architecture in Scotland, such as King's College, Aberdeen.

Domestic

- Anne Hathaway's Cottage, Stratford Upon Avon, Warwickshire: typical 16th-century farmhouse; contains many original features of the house as it would have been in the 1580s.

- Athelhampton House, Dorchester, Dorset - early Tudor

- The Barbican, Devon, Plymouth

- Bishop Percy House, Bridgnorth, Shropshire

- Burghley House, Stamford, Lincolnshire

- Castle Lodge, Ludlow, Shropshire

- Charlecote Park, Warwickshire

- Compton Wynyates, Warwickshire

- Conquest House, Canterbury, Kent

- East Barsham Manor, Norfolk

- Eastbury Manor House, London

- Eltham Palace, Greenwich, London

- Ford's Hospital, Coventry

- The Guildhall in Thaxted, Essex

- Hampton Court Palace, London

- Henley Street, Stratford Upon Avon, Warwickshire-historic district of the entire town, includes the birthplace of William Shakespeare, a large Tudor edifice constructed c. 1570's.

- Hunsdon House, Hertfordshire

- Kenilworth Castle, Kenilworth, Warwickshire – retains many elements from Robert Dudley's 1570s design

- Layer Marney Tower, Essex

- Mill Street, Warwick, Warwickshire

- Mapledurham House, Mapledurham, Oxfordshire

- Montacute House, Somerset – late Tudor

- Nonsuch Palace – perhaps the grandest of Henry VIII's building projects

- Old Market Hall, Shrewsbury

- Owlpen Manor, Gloucestershire

- Oxburgh Hall, Norfolk

- Gatehouse of Richmond Palace, London – early Tudor

- Shaw House, Newbury, Berkshire

- Sir Thomas Herbert's House, Pavement, York

- Sutton House, London Borough of Hackney

- Sutton Place, Surrey – c. 1525

- Tudor Barn Eltham, London[13]

- Wollaton Hall, Nottinghamshire – late Tudor

As a modern term

In the 19th century a free mix of late Gothic elements, Tudor, and Elizabethan were combined for public buildings, such as hotels and railway stations, as well as for residences. The popularity continued into the 20th century for residential building. This type of Renaissance Revival architecture is called 'Tudor,' 'Mock Tudor,' 'Tudor Revival,' and 'Jacobethan.'

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tudor style architecture. |

References

- 1 2 3 4 Picard, Liza (2003). Elizabeth's London. London: Phoenix. ISBN 0-7538-1757-8.

- ↑ http://www.richmond.gov.uk/local_history_richmond_palace.pdf

- ↑ http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/property/luxury-homes/10744402/Inside-Wrens-3m-Wardrobe.html

- ↑ http://www.britainexpress.com/architecture/perpendicular.htm

- ↑ http://englishhistoryauthors.blogspot.com/2015/12/a-not-so-cool-yule-at-sheen-palace-1497.html

- ↑ Weir, Alison (2013). Elizabeth of York: A Tudor Queen and Her World (1st ed.). pg 215: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0345521378.

- ↑ http://englishhistoryauthors.blogspot.com/2012/07/lost-palace-of-richmond.html

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/england/london/8651854.stm

- ↑ Pragnall, Hubert (1984). Styles of English Architecture. Frome: Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-3768-5.

- ↑ Airs, Malcolm (1982). Service, Alastair, ed. Tudor and Jacobean. The Buildings of Britain. London: Barrie and Jenkins. ISBN 0-09-147830-8.

- 1 2 Quiney, Anthony (1989). Period Houses, a guide to authentic architectural features. London: George Phillip. ISBN 0-540-01173-8.

- ↑ Eakins, Lara E. ""Black and White" Tudor Buildings". Tudorhistory.org. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ↑ "About us". Tudor Barn Eltham. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

Tudor Barn Eltham is all that remains of the country mansion that was built for William Roper and Margaret More, daughter of Thomas More, Lord Chancellor to Henry VIII[,] and is surrounded by a medieval moat and nearby scented gardens. The venue is situated in thirteen acres of beautiful award winning gardens and has stood on this ancient site, which is connected historically with the Tudor Monarchs´ residence at nearby Eltham Palace, since 1525.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

- Garner, Thomas and Arthur James Stratton, Domestic Architecture of England during the Tudor Period. London: B.T. Batsford, 1908–1911.

External links

| |||||||||||||||||||||