2015 Atlantic hurricane season

| |

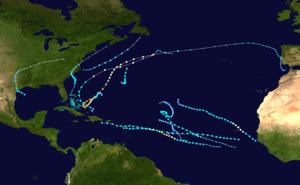

| Season summary map | |

| First system formed | May 8, 2015 |

|---|---|

| Last system dissipated | November 11, 2015 |

| Strongest storm1 | Joaquin – 931 mbar (hPa) (27.49 inHg), 155 mph (250 km/h) |

| Total depressions | 12 |

| Total storms | 11 |

| Hurricanes | 4 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 2 |

| Total fatalities | 88 direct, 2 indirect |

| Total damage | ≥ $588.1 million (2015 USD) |

| 1Strongest storm is determined by lowest pressure | |

2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 | |

| Related article | |

The 2015 Atlantic hurricane season was a slightly below average season featuring eleven named storms, in which four reached hurricane status. It officially began on June 1 and ended on November 30. These dates historically describe the period each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. However the first named storm, Ana, developed nearly a month before the official start of the season, the first since 2012’s Beryl and the earliest since 2003’s Ana. The season ended with the dissipation of Kate 18 days before the official end.

Due to a strong El Niño, most agencies predicted that only 6–10 tropical cyclones would develop; however, the number of tropical cyclones that developed this season exceeded this prediction.

Most storms remained weak, in which they affected few land masses. Tropical Storm Bill affected Texas during mid-June and remained over land for a few days which caused extreme flooding. In August, despite a strong El Niño becoming evident, eight systems continuously developed, most of which formed near and affected the Cape Verde Islands. Erika affected the Lesser Antilles and was known for the worst natural disaster in Dominica since Hurricane David in 1979 with 36 total fatalities and damages of more than $500 million, while Fred become the first hurricane to strike the Cape Verde Islands in over a century. A month later, in late-September, Joaquin developed and strengthened into a Category 4 major hurricane and affected the Bahamas and Bermuda with damages around $60 million and a similar number of attributable deaths as Erika. Henri and Kate's remnants affected Europe in September and November, respectively.

Seasonal forecasts

| Source | Date | Named | Hurricanes | Major | Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average (1981–2010) | 12.1 | 6.4 | 2.7 | [1] | ||

| Record high activity | 28 | 15 | 7 | [2] | ||

| Record low activity | 4 | 2† | 0† | [2] | ||

| ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– | ||||||

| TSR | December 9, 2014 | 13 | 6 | 2 | [3] | |

| TSR | April 9, 2015 | 11 | 5 | 2 | [4] | |

| CSU | April 9, 2015 | 7 | 3 | 1 | [5] | |

| NCSU | April 13, 2015 | 4–6 | 1–3 | 1 | [6] | |

| UKMO | May 21, 2015 | 8* | 5* | N/A | [7] | |

| NOAA | May 27, 2015 | 6–11 | 3–6 | 0–2 | [8] | |

| CSU | June 1, 2015 | 8 | 3 | 1 | [9] | |

| TSR | August 5, 2015 | 11 | 4 | 1 | [10] | |

| NOAA | August 6, 2015 | 6–10 | 1–4 | 0–1 | [11] | |

| ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– | ||||||

| Actual activity |

11 | 4 | 2 | |||

| * June–November only † Most recent of several such occurrences. (See all) | ||||||

Forecasts of hurricane activity are issued before each hurricane season by noted hurricane experts Philip J. Klotzbach, William M. Gray, and their associates at Colorado State University (CSU); and separately by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) forecasters.

Klotzbach's team (formerly led by Gray) defined the average number of storms per season (1981 to 2010) as 12.1 tropical storms, 6.4 hurricanes, 2.7 major hurricanes (storms reaching at least Category 3 strength on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale), and an Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) index of 96.1.[12] NOAA defines a season as above-normal, near-normal or below-normal by a combination of the number of named storms, the number reaching hurricane strength, the number reaching major hurricane strength, and the ACE index.[13]

Pre-season forecasts

On December 9, 2014, Tropical Storm Risk (TSR), a public consortium consisting of experts on insurance, risk management, and seasonal climate forecasting at University College London, issued its first outlook on seasonal hurricane activity during the 2015 season. In its report, the organization forecast activity about 20% below the 1950–2014 average, or about 30% below the 2005–2014 average, totaling to 13 (±4) tropical storms, 6 (±3) hurricanes, 2 (±2) major hurricanes, and a cumulative ACE index of 79 (±58) units. This forecast was largely based on an enhancement of low-level trade winds across the tropical Atlantic during the July to September period. TSR's report stressed that uncertainty in this forecast existed due to the unpredictability in the El Niño Southern Oscillation and North Atlantic sea surface temperatures.[3] A few months later, on April 9, 2015, the organization updated its report, detailing its prediction of activity 45% below the 1950–2014 average, or about 50% below the recent 2005–2014 average, with 11 named storms, 5 hurricanes, 2 major hurricanes, and a cumulative ACE index of 56 units. TSR cited what were expected to be cooler than average ocean temperatures across the tropical North Atlantic and Caribbean Sea as reasoning for lower activity. In addition, the report stated that if the ACE forecast for 2015 were to verify, the total values during the three-year period from 2013–2015 would be the lowest since 1992–1994, signalling a possible end to the active phase of Atlantic hurricane activity that began in 1995.[4]

On April 9, CSU also released its first quantitative forecast for the 2015 hurricane season, predicting 7 named storms, 3 hurricanes, 1 major hurricane, and a cumulative ACE index of 40 units. The combination of cooler than average waters in the tropical and subtropical Atlantic, as well as a developing El Niño predicted to reach at least moderate intensity, were expected to favor one of the least active seasons since the mid-1990s. The probabilities of a major hurricane striking various coastal areas across the Atlantic were lower than average, although CSU stressed that it only takes one landfalling hurricane to make it an active season for residents involved.[5] On April 13, North Carolina State University (NCSU) released its forecast, predicting a near record-low season with just 4 to 6 named storms, 1 to 3 hurricanes, and 1 major hurricane.[6]

On May 21, the United Kingdom Met Office (UKMO) issued its forecast, predicting a season with below-normal activity. It predicted 8 storms, with a 70% chance that the number of storms would be between 6 and 10; it predicted 5 hurricanes, with a 70% chance that that number would fall in the range of 3 to 7. UKMO's ACE index prediction was 74 units, with a 70% chance of the index falling in the range of 40 to 108 units.[7] On May 27, NOAA released its seasonal forecast, predicting a below-normal season with 6 to 11 named storms, 3 to 6 hurricanes, and 0 to 2 major hurricanes. NOAA indicated that there was a 70% chance of a below-normal season, a 20% chance of a near-normal season, and a 10% chance of an above-normal season.[8]

Mid-season outlooks

On June 1, CSU released an updated forecast, increasing the number of predicted named storms to 8, due to the early formation of Tropical Storm Ana, while keeping the predictions for hurricanes and major hurricanes at 3 and 1, respectively; the ACE index forecast was also kept at 40 units. Probabilities of a major hurricane making landfall on various coastal areas remained below average.[9] On August 5, TSR updated their forecast and lowered the number of hurricanes developing within the basin to 4, with only 1 forecasted to be a major hurricane. The ACE index was also reduced to 44 units.[10]

Seasonal summary

The season's first storm, Ana, developed nearly a month before the official start of the season. Next month, Tropical Storm Bill caused torrential rain in the Southern Plains. Tropical Storm Claudette caused minimal damage while tropical. Despite an El Niño over the Pacific, conditions became more favorable for tropical cyclogenesis over the Cape Verde Islands and the west coast of Africa as eight systems formed continuously beginning on mid-August. Danny became the first major hurricane. Erika then produced torrential rain in the Caribbean and Florida, despite remaining unorganized. Fred produced measurable impact on the Cape Verde Islands following crossing them as a hurricane for the first time since 1892. Grace, Henri, Tropical Depression Nine and Ida caused minimal, if any, damage. The strongest and longest-lived storm of the season, Joaquin caused considerable damage in The Bahamas and Bermuda as a Category 4 and Category 2, respectively. The final system of the season, Kate, moved through the Bahamas as a tropical storm before reaching weak hurricane status. Kate's remnants affected Europe.

The Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) for the season was 62.685 units.[nb 1]

Storms

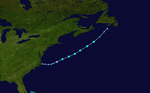

Tropical Storm Ana

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | May 8 – May 11 | ||

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 998 mbar (hPa) | ||

A low pressure area of non-tropical origins developed into Subtropical Storm Ana at 00:00 UTC on May 8, while situated about 175 miles (280 km) of Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. The system was classified as subtropical due to its involvement with an upper trough, as well as its large wind field. Throughout the day, convection progressively increased as Ana moved north-northwestward across the warm sea surface temperatures associated with the Gulf Stream. At 00:00 UTC on May 9, the cyclone attained its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 60 miles per hour (95 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 998 millibars (29.5 inHg). Six hours later, Ana transitioned into a fully tropical system. However, the storm soon began weakening after moving away from the warm waters of the Gulf Stream and increasing wind shear also contributed to the deterioration of Ana. Around 10:00 UTC on May 10, the system made landfall near North Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, with winds of 45 mph (75 km/h). Ana weakened to a tropical depression just eight hours later and transitioned into a remnant low near the Delmarva Peninsula at 00:00 UTC on May 12. The remnant low merged with a frontal system about 24 hours later.[14]

Striking South Carolina on May 10, Ana became the earliest U.S. landfalling system on record. In the state, a storm surge peaking at about 2.5 feet (0.76 m) resulted in erosion and minor coastal flooding,[14] with roads washed out at North Myrtle Beach.[15] Inland, moderate rainfall caused a lake to rise above its bank, inundating some homes and streets.[16] One drowning death occurred in North Carolina after rip currents caused a man to remain underwater for more than 10 minutes. Rainfall in the state peaked at 6.7 inches (170 mm) southeast of Kinston, North Carolina, where minor street flooding took place. In Lenoir County, local firefighters rescued several stranded individuals by boat when rising floodwaters isolated about 10 residences.[14] Tropical storm-force winds were confined to coastal areas, with a peak gust of 62 mph (100 km/h) observed near Southport.[17] An additional death occurred in North Carolina after a tree fell on a car in Richlands.[14]

Tropical Storm Bill

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | June 16 – June 18 | ||

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 997 mbar (hPa) | ||

The National Hurricane Center (NHC) began monitoring disorganized convection across the northwestern Caribbean Sea in association with an upper-level trough on June 12.[18] After interacting with a broad area of low pressure near the Yucatán Peninsula, an elongated area of low pressure formed in the vicinity on June 13. The system moved northwestward into the Gulf of Mexico and developed a well-defined circulation on early June 16. Because the system was already producing tropical storm force winds, it was immediately classified as Tropical Storm Bill while situated about 200 mi (320 km). Initially continuing northwestward, Bill re-curved west-northwestward later on June 16. Around 12:00 UTC, the storm peaked with winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 997 mbar (29.4 inHg). Just under five hours later, Bill made landfall near on Matagorda Island, Texas, at the same intensity. The cyclone weakened to a tropical depression and turned northward early on June 17.[19] However, possibly due to the rare brown ocean effect,[20] Bill remained a tropical cyclone until late on June 18, when it degenerated into a remnant low. The remnant low moved east-northeastward until dissipating over West Virginia on June 21.[19]

The precursor to Bill produced widespread heavy rain in Central America. In Guatemala, flooding affected more than 100 homes while a landslide killed two people.[21] Two others died in Honduras due to flooding with two more missing.[22] Heavy rains fell across parts of the Yucatán Peninsula, with accumulations peaking at 13 in (330 mm) in Cancún, the highest daily total seen in the city in nearly two years. One person died from electrocution in the city.[23] In Texas, flooding was exacerbated by record rainfall in some areas in May. A number of roads were inundated and several water rescues were required in Alice and San Antonio. Major traffic jams occurred in the Houston and Dallas areas. Coastal flooding left minor damage, mostly in Galveston and Matagorda counties.[19] One death occurred when a boy was swept into a culvert.[24] In Oklahoma, numerous roads were also inundated by water. Interstate 35 was closed near Turner Falls due to a rockslide and near Ardmore because of high water. There were two fatalities in Oklahoma, both from drowning. There was also flooding in several others states.[19] Across the United States, Bill was responsible for approximately $17.9 million in damage.[25]

Tropical Storm Claudette

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | July 13 – July 14 | ||

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 1003 mbar (hPa) | ||

In early July, a shortwave trough embedded in the westerlies crossed the United States. The system emerged over the Atlantic near the Outer Banks of North Carolina on July 12; a surface low soon developed. Traversing the Gulf Stream, convection abruptly increased on July 13 and it is estimated that a tropical depression formed by 06:00 UTC that day, roughly 255 mi (410 km) east-northeast of Cape Hatteras. Six hours later, the depression intensified into a tropical storm and was assigned the name Claudette. The sudden development of the cyclone was not well-forecast,[26] and Claudette was not operationally warned upon until it was already a tropical storm.[27] Embedded within southwesterly flow ahead of mid-latitude trough, the storm moved generally northeast. Claudette reached its peak intensity around 18:00 UTC with winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) and a pressure of 1003 mbar (hPa; 29.62 inHg). Increasing wind shear on July 14 prompted weakening, displacing convection from the storm's center. It subsequently degenerated into a remnant low by 00:00 UTC on July 15. The remnants of Claudette were absorbed into a frontal boundary just south of Newfoundland later that day.[26]

Foggy and wet conditions associated with Claudette forced flight cancellations and travel delays across portions of eastern Newfoundland.[28]

Hurricane Danny

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | August 18 – August 24 | ||

| Peak intensity | 125 mph (205 km/h) (1-min) 960 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical wave emerged off the western coast of Africa in mid-August, acquiring sufficient organization to be declared a tropical depression by 06:00 UTC on August 18 while located about 765 mi (1,230 km) southwest of Cape Verde. The depression intensified into Tropical Storm Danny six hours later. Steered generally westward, the cyclone initially struggled to intensify quickly in the midst of abundant Saharan Air Layer (SAL), but it managed to attain hurricane intensity around 12:00 UTC on August 20. Thereafter, Danny began a period of rapid deepening, becoming a Category 3 hurricane and attaining peak winds of 125 mph (205 km/h) early on August 21. The negative effects of dry air and increased shear began to affect the cyclone after peak.[29]

Early on August 22, the storm weakened to a Category 2 and further to a Category 1 hurricane several hours later. Danny then deteriorated to a tropical storm by 00:00 UTC on August 23. After about twelve hours, the cyclone weakened to a tropical depression as it moved through the Leeward Islands. Danny degenerated into an open wave at 18:00 UTC on August 24. The remnants of Danny continued to the west-northwest for another day and was last noted over Hispaniola. The hurricane prompted the issuance of several tropical storm warnings for the Lesser Antilles.[29] Leeward Islands Air Transport cancelled 40 flights and sandbags were distributed in the United States Virgin Islands.[30][31] Danny ultimately only brought light rain to the region, with its effects considered beneficial due to a severe drought.[29]

Tropical Storm Erika

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | August 24 – August 28 | ||

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 1001 mbar (hPa) | ||

A westward-moving tropical wave developed into Tropical Storm Erika late on August 24 while located about 1,035 mi (1,665 km) east of the Leeward Islands. Steered briskly westward by southerly flow associated with a subtropical ridge, the storm did not strengthen further despite initially favorable conditions. On August 25, Erika encountered wind shear and dry mid-level air, causing the storm to weaken slightly and leaving the low-level circulation partially exposed. Contrary to predictions of a northwesterly recurvature, the cyclone persisted on a westerly course and passed through the Leeward Islands just north of Guadeloupe on August 27. Unfavorable conditions in the Caribbean Sea prevented Erika from strengthening beyond 50 mph (85 km/h). Late on August 28, the storm degenerated into a low pressure area just south of the eastern tip of Hispaniola. Shortly thereafter, the remnants trekked across Hispaniola and later Cuba, before reaching the Gulf of Mexico on September 1. After striking Florida on the following day, the remains of Erika became indistinguishable over Georgia on September 3.[32]

Several Leeward Islands experienced heavy rainfall during the passage of Erika, especially Dominica. There, 15 in (380 mm) of precipitation fell at Canefield Airport,[33][34] causing catastrophic mudslides and flooding. A total of 890 homes were destroyed or left uninhabitable while 14,291 people were rendered homeless, and entire villages were flattened.[35] With at least 31 deaths, Erika was the deadliest natural disaster in Dominica since David in 1979.[36][37] Overall, there was up to $500 million in damage and the island was set back approximately 20 years in terms of development.[32][38] In Guadeloupe, heavy rainfall in the vicinity of Basse-Terre caused flooding and mudslides, forcing roads to temporarily close.[39] Approximately 200,000 people in Puerto Rico were left without electricity.[40] The island experienced at least $17.4 million in agricultural damage.[32] In the Dominican Republic, a weather station in Barahona measured 24.26 in (616 mm) of rain, including 8.8 in (220 mm) in a single hour.[41] About 823 homes suffered damage and 7,345 people were displaced.[42] Five people died in Haiti, four from a weather-related traffic accident and one from a landslide.[43]

Hurricane Fred

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | August 30 – September 6 | ||

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min) 986 mbar (hPa) | ||

A well-defined tropical wave developed into a tropical depression about 190 mi (310 km) west-northwest of Conakry, Guinea, early on August 30. About six hours later, the depression intensified into a tropical storm. The next day, Fred further grew to a Category 1 hurricane and several hours later peaked with winds of 85 mph (140 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 986 mbar (29.1 inHg) while approaching Cape Verde. After passing Boa Vista and moving away from Santo Antão, it entered a phase of steady weakening, dropping below hurricane status by September 1. Fred then turned to the west-northwest and endured increasingly hostile wind shear,[44] but maintained its status as a tropical cyclone despite repeated forecasts of dissipation.[45] It fluctuated between a minimal tropical storm and tropical depression through September 4–5 before curving sharply to the north. By September 6, Fred's circulation pattern had diminished considerably and the cyclone degenerated into a trough several hours later while located about 1,210 mi (1,950 km) southwest of the Azores. The remnants were soon absorbed by a frontal system.[44]

At the threat of the hurricane, all of Cape Verde was placed under a hurricane warning for the first time in history.[46] Gale-force winds battered much of the Barlavento region through August 31, downing numerous trees and utility poles.[47] On the easternmost islands of Boa Vista and Sal, Fred leveled roofs and left several villages without power and phone services for several days. About 70 percent of the houses in Povoação Velha were damaged to some degree.[48] Throughout the northern islands, rainstorms damaged homes and roads, and São Nicolau lost large amounts of its crop and livestock.[49] Monetary losses exceeded $1.1 million across Cape Verde,[50] though the rain's overall impact on the agriculture was positive.[51] Swells from the hurricane produced violent seas along West African shores, destroying fishing villages and submerging large swaths of residential area in Senegal.[52] Overall, nine deaths were directly attributed to Fred.[44]

Tropical Storm Grace

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | September 5 – September 9 | ||

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 1000 mbar (hPa) | ||

A well-organized tropical wave emerged off the western coast of Africa on September 3. Initially disorganized with a broad area of low pressure, a burst of convection on September 5 led to a more concise center, and a tropical depression developed around 06:00 UTC that day while positioned about 175 mi (280 km) south of Cape Verde. The depression intensified into Tropical Storm Grace twelve hours later. Embedded within a generally favorable environment, Grace strengthened to attain peak winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) around 12:00 UTC on September 6, when a mid-level eye feature was evident on satellite. Thereafter, cooler waters and increased shear caused the cyclone to weaken to a tropical depression early on September 8 and dissipate at 12:00 UTC the next day while located within the central Atlantic.[53]

Tropical Storm Henri

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | September 8 – September 11 | ||

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 1003 mbar (hPa) | ||

On September 8, an upper-level trough spawned a tropical depression southeast of Bermuda; the next day it was upgraded to Tropical Storm Henri. Struggling against strong westerly wind shear, the system attained a peak intensity of 50 mph (85 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 1003 mbar (hPa), possibly due to baroclinity. Operationally, the NHC put Henri's peak intensity at only 40 mph (65 km/h). Thereafter, increasing interaction with the same upper-level trough to the west degraded Henri's circulation. It opened up into a trough on September 11; the remnants were later absorbed into a non-tropical cyclone over the North Atlantic several days later.[54]

Tropical Depression Nine

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | September 16 – September 19 | ||

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min) 1006 mbar (hPa) | ||

On September 10, a strong tropical wave emerged off the western coast of Africa. Passing south of Cape Verde, its interaction with a convectively-coupled kelvin wave resulted in increased convection and the formation of an area of low pressure. After further organization, the wave acquired sufficient organization to be declared a tropical depression by 12:00 UTC on September 16 while located within the central Atlantic. Unfavorable upper-level winds caused the appearance of the cyclone to become disheveled almost immediately after formation, and despite sporadic bursts of convection atop the storm's center, the depression dissipated at 18:00 UTC on September 19 without ever attaining tropical storm intensity.[55]

Tropical Storm Ida

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | September 18 – September 27 | ||

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 1001 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical wave emerged into the Atlantic from the west coast of Africa on September 13. The wave later interacted with a Kelvin wave, the latter of which contributed to the formation of Tropical Depression Nine. Moving westward with a large area of convection, the tropical wave and the Kelvin developed into a well-defined low pressure area around midday on September 15, according to satellite imagery. However, disorganized prevented its classification as a tropical depression until 06:00 UTC on September 18, while located about 750 mi (1,210 km) south of the southernmost Cape Verde Islands. The depression moved west-northwestward due to a subtropical ridge to the north and intensified into Tropical Storm Ida early the following day. Westerly wind shear exposed the storm's low-level circulation, causing Ida to strengthen only slightly.[56]

Wind shear briefly decreased, allowing the cyclone to peak with winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 1,001 mbar (29.6 inHg) at 12:00 UTC on September 21. However, shear increased later that day, causing slow weakening. Ida then decelerated and began moving in a general eastward direction on September 22 after becoming embedded in the flow associated with an mid- to upper-level trough. Early on September 24, the storm weakened to a tropical depression. During the following day, the trough was replaced with a subtropical ridge, causing Ida to turn northwestward and then west-northwestward on September 26. After shear and dry air caused much of the convection to diminish, Ida degenerated into a remnant low around 12:00 UTC on September 27 while situated about 1,000 mi (1,610 km) east-northeast of Barbuda.[56]

Hurricane Joaquin

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | September 28 – October 8 | ||

| Peak intensity | 155 mph (250 km/h) (1-min) 931 mbar (hPa) | ||

A non-tropical low developed into a tropical depression on September 28 about 405 mi (650 km) southwest of Bermuda, based on the improved circulation on satellite imagery.[57] Convection increased and organized around the center as the wind shear decreased, resulting in the depression being upgraded to Tropical Storm Joaquin early on September 29. The storm initially moved generally westward or southwestward, steered by a high pressure area to the north.[58] The cloud pattern became better organized as Joaquin moved toward the Bahamas.[59] On September 30, the storm intensified into a hurricane, as reported by the Hurricane Hunters.[60] Joaquin then rapidly deepened, becoming a Category 4 hurricane late on October 1.[61] Joaquin later weakened as it passed through the Bahamas,[62] but reintensified to a Category 4 hurricane while recurving northeastward.[63] On October 3, maximum sustained winds peaked at 155 mph (250 km/h), just below Category 5 strength.[64] Thereafter, Joaquin began to rapidly weaken as it approached Bermuda. The cyclone then turned eastward and maintained hurricane status until October 7.[65] By the following day, Joaquin became extratropical about 350 mi (565 km) west-northwest of Corvo Island in the Azores.[66]

Battering the Bahamas's southern islands for over two days, Joaquin caused extensive devastation, especially on Acklins, Crooked Island, Long Island, Rum Cay, and San Salvador Island.[67] Severe storm surge inundated many communities, trapping hundreds of people in their homes; flooding persisted for days after the hurricane's departure.[68][69] Prolonged, intense winds brought down trees and powerlines, and unroofed homes throughout the affected region.[70] As airstrips were submerged and heavily damaged, relief workers were limited in their ability to quickly help affected residents.[71] Offshore, the American cargo ship El Faro and her 33 crew members were lost to the hurricane.[72] Coastal flooding also impacted the Turks and Caicos, washing out roadways, compromising seawalls, and damaging homes.[73] Strong winds and heavy rainfall caused some property damage in eastern Cuba.[74] One fisherman died when heavy seas capsized a small boat along the coast of Haiti.[71] Storm tides resulted in severe flooding in several of Haiti's departments, forcing families from their homes and destroying crops.[75] The storm brought strong winds to Bermuda that cut power to 15,000 customers.[76] Damage on Bermuda was minor.[77] Although Joaquin steered clear of the mainland United States, another large storm system over the southeastern states drew tremendous moisture from the hurricane, resulting in catastrophic flooding in South Carolina.[78]

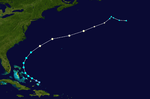

Hurricane Kate

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | November 8 – November 11 | ||

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min) 980 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical wave, which had heavy thunderstorm activity over the northern Lesser Antilles, was interacting with an upper-level low pressure area by late on November 4.[79] A low pressure area formed near the Turks and Caicos Islands on November 7.[80] Late on the following day, satellite imagery indicated that the circulation became well-defined. As a result, Tropical Depression Twelve developed about 115 mi (190 km) southeast of San Salvador Island in the Bahamas around 03:00 UTC on November 9. Amid generally favorable atmospheric conditions,[81] the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Kate several hours later.[82] After initially moving northwestward, Kate briefly accelerated northward around the western periphery of a subtropical ridge over the central Atlantic.[83] Thereafter, the cyclone accelerated further and curved northeastward due to the mid-latitude westerlies.[84]

After intensification and improvements to convective banding, Kate was upgraded to a Category 1 hurricane at 09:00 UTC and peaked with sustained winds of 75 mph. (120 km/h).[85] This was later upgraded to 85 mph in Post-Storm Analysis. Due to very strong wind shear and decreasing sea surface temperatures, the storm began losing tropical characteristics shortly thereafter.[86] The hurricane weakened to a tropical storm early on November 12, as the cloud pattern became elongated and asymmetrical.[87] However, around that time, Kate attained its lowest barometric pressure of 983 mbar (29.03 inHg).[88] By 09:00 UTC on November 12, the system became extratropical about 430 mi (690 km) south-southeast of Cape Race, Newfoundland, after merging with a baroclinic zone.[89] The remnants of Kate moved north of the British Isles and affected the United Kingdom and Ireland on November 15 and 16.[90][91]

Across Wales, high winds downed trees and heavy rain flooded roadways.[92]

Storm names

The following list of names will be used for named storms that form in the North Atlantic in 2015. Retired names, if any, will be announced by the World Meteorological Organization in the spring of 2016. The names not retired from this list will be used again in the 2021 season list. This is the same list used in the 2009 season. The name Joaquin replaced Juan after 2003, but was not used in 2009; therefore, it was used for the first time this year.[93]

|

|

Season effects

This is a table of all of the storms that have formed during the 2015 Atlantic hurricane season. It includes their names, duration, peak strength, areas affected, damage, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all of the damage figures are in 2015 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category

at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (millions USD) |

Deaths | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ana | May 8 – 11 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 998 | Southeastern United States | Minimal | 1 (1) | |||

| Bill | June 16 – 18 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 997 | Central America, Yucatán Peninsula, South Central United States, Midwestern United States | 17.9 | 8 (1) | |||

| Claudette | July 13 – 14 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1003 | East Coast of the United States, Newfoundland | None | None | |||

| Danny | August 18 – 24 | Category 3 hurricane | 125 (205) | 960 | Lesser Antilles, Puerto Rico | Minor | None | |||

| Erika | August 25 – 29 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1003 | Lesser Antilles (Dominica), Greater Antilles, Florida | 509.1 | 36 | |||

| Fred | August 30 – September 6 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 986 | West Africa, Cape Verde | >1.1 | 9 | |||

| Grace | September 5 – 9 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 1000 | None | None | None | |||

| Henri | September 8 – 11 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1003 | None | None | None | |||

| Nine | September 16 – 19 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1006 | None | None | None | |||

| Ida | September 18 – 27 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1001 | None | None | None | |||

| Joaquin | September 28 – October 8 | Category 4 hurricane | 155 (250) | 931 | Turks and Caicos Islands, The Bahamas, Cuba, Haiti, Southeastern United States, Bermuda, Azores, Iberian Peninsula | >60 | 34 | |||

| Kate | November 8 – 11 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 980 | The Bahamas, United Kingdom, Ireland | Minimal | None | |||

| Season Aggregates | ||||||||||

| 12 cyclones | May 8 – November 11 | 155 (250) | 931 | ≥588.1 | 88 (2) | |||||

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 2015 Atlantic hurricane season. |

- List of Atlantic hurricanes

- 2015 Pacific hurricane season

- 2015 Pacific typhoon season

- 2015 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 2014–15, 2015–16

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 2014–15, 2015–16

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 2014–15, 2015–16

- South Atlantic tropical cyclone

Footnotes

- ↑ The totals represent the sum of the squares for every (sub)tropical storm's intensity of over 33 knots (38 mph, 61 km/h), divided by 10,000. Calculations are provided at Talk:2015 Atlantic hurricane season/ACE calcs.

References

- ↑ "Background Information: The North Atlantic Hurricane Season". Climate Prediction Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. August 9, 2012. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- 1 2 National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division (June 4, 2015). "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 15, 2016.

- 1 2 Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (December 9, 2014). Extended Range Forecast for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2015 (PDF). Tropical Storm Risk (Report) (London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk). Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- 1 2 Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (April 9, 2014). April Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2015 (PDF). Tropical Storm Risk (Report) (London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk). Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- 1 2 Phillip J. Klotzbach; William M. Gray (April 9, 2015). "Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and Landfall Strike Probability for 2015" (PDF). Colorado State University. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- 1 2 "Expect Quiet Hurricane Season, NC State Researchers Say" (PDF). North Carolina State University. North Carolina State University. April 13, 2015. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- 1 2 "North Atlantic tropical storm seasonal forecast 2015". Met Office. May 21, 2015. Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- 1 2 "NOAA: Below-normal Atlantic Hurricane Season is likely this year". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 27, 2015. Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- 1 2 Phillip J. Klotzbach; William M. Gray (June 1, 2015). "Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and Landfall Strike Probability for 2015" (PDF). Colorado State University. Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- 1 2 Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (August 5, 2015). April Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2015 (PDF). Tropical Storm Risk (Report) (London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk). Retrieved August 5, 2015.

- ↑ "Increased likelihood of below-normal Atlantic hurricane season". Climate Prediction Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. August 6, 2015. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- ↑ Philip J. Klotzbach and William M. Gray (December 10, 2008). "Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and U.S. Landfall Strike Probability for 2009" (PDF). Colorado State University. Archived from the original on June 12, 2009. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ↑ "NOAA's Atlantic Hurricane Season Classifications". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. National Hurricane Center. May 22, 2008. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Stacy R. Stewart (September 15, 2015). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Ana (PDF). National Hurricane Center (Report) (Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- ↑ Liz Cooper (May 10, 2015). "Impacts of Ana along the Grand Strand". WPDE Carolina Live. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- ↑ James Hopkins (May 11, 2015). "Ana causes flooding, beach erosion in North Myrtle Beach". WBTW (Myrtle Beach, South Carolina). Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- ↑ Public Information Statement. National Weather Service Office in Wilmington, North Carolina (Report) (Wilmington, North Carolina: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). May 10, 2015. Archived from the original on May 10, 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- ↑ Eric S. Blake and James L. Franklin (June 12, 2015). Tropical Weather Outlook valid 200 pm EDT Fri Jun 12 2015. National Hurricane Center (Report) (Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Robbie J. Berg (September 9, 2015). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Bill (PDF). National Hurricane Center (Report) (Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ↑ Jeff Masters and Bob Henson (15 June 2015). "Dangerous Flood Potential in Texas, Oklahoma from Invest 91L".

- ↑ Wendy Sandoval (June 14, 2015). "Deslaves dejan segunda víctima en Alta Verapaz". Siglo21 (in Spanish). Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- ↑ "Lluvias causan dos muertos y daños". La Prensa Grafica (in Spanish). June 16, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ↑ ""Carlos", otra vez ciclón". Diario de Yucatán (in Spanish). =El Universal. June 16, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ↑ Texas Event Report: Flash Flood. National Weather Service Office in Fort Worth, Texas (Report) (National Climatic Data Center). 2015. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ↑ "Storm Events Database". National Climatic Data Center. 2015. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

- 1 2 Lixion A. Avila (August 14, 2015). Tropical Storm Claudette (PDF) (Report). Tropical Cyclone Report. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 30, 2015.

- ↑ Daniel P. Brown (July 13, 2015). Tropical Storm Claudette Special Advisory Number 1 (Advisory). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 30, 2015.

- ↑ "Post-tropical storm Claudette flight cancellations plague travellers". CBC News. July 15, 2015. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Stacy R. Stewart (January 19, 2016). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Danny (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Puerto Rico, USVI prepare for Tropical Storm Danny". Jamaica Observer (San Juan, Puerto Rico). Associated Press. August 23, 2015. Retrieved January 28, 2016.

- ↑ Jenny Staletovich and Jacqueline Charles (August 21, 2015). "Hurricane Danny raises worry in Caribbean; expected to weaken over weekend". Miami Herald (Miami, Florida). Retrieved January 28, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Richard J. Pasch and Andrew B. Penny (February 6, 2016). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Erika (PDF). National Hurricane Center (Report) (Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Retrieved February 12, 2016.

- ↑ Carlisle Jno Paptiste and Danica Coto (August 27, 2015). "5 missing in Dominica as Tropical Storm Erika unleashes heavy rain, wind, landslides". U.S. News & World Report (Roseau, Dominica). Associated Press. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- ↑ "Tropical Storm Erika: At Least 2 Dead, Widespread Flooding Reported in Dominica; Florida Prepares For Possible Impacts". The Weather Channel. August 27, 2015. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- ↑ Ashley Mayrianne Jones (October 3, 2015). "Month after Erika, Dominica destruction 'jaw-dropping'". Virgin Islands Daily News. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved October 8, 2015.

- ↑ "At least 27 dead in Petite Savanne following Erika". The Dominican. August 28, 2015. Retrieved August 28, 2015.

- ↑ "Dominica pleads for help as storm death toll tops 30". Yahoo News. Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- ↑ "Nine dead, others missing after Tropical Storm Erika's deluge hits Dominica". CNN. August 28, 2015. Retrieved August 29, 2015.

- ↑ Laurie-Anne Virassamy (August 27, 2015). "Erika perturbe la Martinique". France Télévisions (in French). Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ↑ "Erika soaks Puerto Rico after 4 killed in Dominica". Newsday (San Juan, Puerto Rico). Associated Press. August 28, 2015. Retrieved August 28, 2015.

- ↑ Jeff Masters (August 29, 2015). "Erika Dissipates". Weather Underground. Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- ↑ "Erika leaves over 7,300 displaced in Dominican Republic". Dominican Today (Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic). August 29, 2015. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ↑ Francisco Jara (August 30, 2015). "Tropical storm Erika drenches parched Cuba". ReliefWeb (Havana, Cuba). Agence France-Presse. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- 1 2 3 John L. Beven II (January 20, 2016). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Fred (PDF). National Hurricane Center (Report) (Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Retrieved February 12, 2016.

- ↑ John L. Beven II (September 2, 2015). Tropical Storm Fred Discussion Number Thirteen (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- Stacy R. Stewart (September 3, 2015). Tropical Storm Fred Discussion Number Eighteen (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- John L. Beven II (September 4, 2015). Tropical Storm Fred Discussion Number Twenty-Two (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ↑ "Primeiro furacão da história, "Fred" ameaça Cabo Verde" (in Portuguese). São Paulo, Brazil: De Olho No Tempo Meteorologia. August 30, 2015. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ↑ "Agricultores de Fajã somam prejuízos com passagem do furação Fred". Ocean Press (in Portuguese) (Santa Maria, Cape Verde). September 1, 2015. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ↑ Sanny Fonseca (2015-09-04). "Boa Vista: Furacão Fred deixa 50 casas destruídas em Povoação Velha". A Semana (in Portuguese) (Praia, Cape Verde). Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ↑ "Furacão Fred: Governo vai precisar de 30 mil contos para intervenções em São Nicolau" (in Portuguese). Praia, Cape Verde. Inforpress. September 8, 2015. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ↑ "Furacão Fred desalojou 50 famílias e causou estragos em todo o país". Sapo Notícias (in Portuguese) (Praia, Cape Verde). Lusa. September 1, 2015. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ↑ Nélio dos Santos (September 7, 2015). "Um verde que renasce do Furacão Fred" (in Portuguese). Bonn, Germany: Deutsche Welle. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ↑ "Sénégal: 200 maisons détruites par la houle à Dakar". StarAfrica (in French). Agence France-Presse. September 1, 2015. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ↑ Eric S. Blake (November 21, 2015). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Grace (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- ↑ Todd B. Kimberlain (October 21, 2015). Tropical Storm Henri (PDF) (Report). Tropical Cyclone Report. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 28, 2015.

- ↑ Daniel P. Brown (November 16, 2015). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Depression Nine (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- 1 2 John P. Cangialosi (November 16, 2015). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Ida (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- ↑ Todd B. Kimberlain (September 28, 2015). "Tropical Depression Eleven Discussion Number 1". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- ↑ John P. Cangialosi (September 29, 2015). "Tropical Storm Joaquin Discussion Number 5". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- ↑ Richard J. Pasch (September 29, 2015). "Tropical Storm Joaquin Discussion Number 8". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- ↑ John L. Beven II (September 30, 2015). "Hurricane Joaquin Public Advisory Number 10A". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2015-09-30.

- ↑ John L. Beven II (October 1, 2015). "Hurricane Joaquin Public Advisory Number 15A". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- ↑ John L. Beven II (October 2, 2015). "Hurricane Joaquin Discussion Number 20". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- ↑ Lixion A. Avila (October 3, 2015). "Hurricane Joaquin Discussion Number 23". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- ↑ Lixion A. Avila (October 3, 2015). "Hurricane Joaquin Special Discussion Number 24". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- ↑ Eric S. Blake (October 7, 2015). "Hurricane Joaquin Discussion Number 30". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- ↑ Richard J. Pasch (October 7, 2015). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Joaquin Advisory Number 42". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Hurricane Joaquin Updates: Multiple Deaths Confirmed, Southern Family Islands "Completely Devastated"". The Tribune. October 3, 2015. Retrieved October 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Prime Minister Christie to Address The Nation with NEMA at Press Briefing Today". The Bahamas Weekly. October 1, 2015. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

- ↑ Sean Breslin (October 1, 2015). "Hurricane Joaquin's Bahamas Impacts: More Than 500 Residents Trapped in Their Homes, Excessive Power Outages". The Weather Channel. Associated Press. Retrieved October 2, 2015.

- ↑ "Communication With Storm-Hit Islands A Challenge". The Tribune. October 2, 2015. Retrieved October 2, 2015.

- 1 2 Hurricane Joaquin - Situation Report #4 as of 8:00 pm on October 4th, 2015 (Report). Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency. October 4, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ↑ Emily Reiter (October 7, 2015). "Coast Guard to suspend search for El Faro crew after 7-day search". United States Coast Guard. Miami, Florida: TOTE Maritime. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ↑ Hurricane Joaquin - Situation Report #6 as of 6:00 pm on October 8th, 2015 (Report). Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency. October 8, 2015. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ↑ Darelia Díaz Borrero (October 2, 2015). "Se prepara Granma para reducir efectos del huracán Joaquín". Granma (in Spanish) (Bayamo, Cuba). Retrieved October 3, 2015.

- ↑ Hurricane Joaquin - Situation Report #7 as of 3:30 pm on October 9th 2015 (Report). Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency. October 9, 2015. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- ↑ Jonathan Bell (October 6, 2015). "West End bears the brunt of Joaquin". The Royal Gazette. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- ↑ Jonathon Bell (October 5, 2015). "BF&M: little property damage". The Royal Gazette. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ↑ Jeff Halverson (October 5, 2015). "The meteorology behind South Carolina’s catastrophic, 1,000-year rainfall event". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ↑ John P. Cangialosi (November 4, 2015). Tropical Weather Outlook Valid 700 pm EDT Fri Jun 12 2015. National Hurricane Center (Report) (Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ↑ John P. Cangialosi and Stacy R. Stewart (November 7, 2015). Tropical Weather Outlook Valid 700 pm EDT Fri Jun 12 2015. National Hurricane Center (Report) (Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ↑ Daniel P. Brown (November 9, 2015). "Tropical Depression Twelve Discussion Number 1". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ↑ John P. Cangialosi and Stacy R. Stewart (November 9, 2015). "Tropical Storm Kate Tropical Cyclone Report". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ↑ Daniel P. Brown (November 10, 2015). "Tropical Storm Kate Discussion Number 5". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ↑ Michael J. Brennan (November 10, 2015). "Tropical Storm Kate Discussion Number 8". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ↑ John L. Beven II (November 11, 2015). "Hurricane Kate Discussion Number 10". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ↑ John P. Cangialosi (November 11, 2015). "Hurricane Kate Discussion Number 11". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ↑ Todd B. Kimberlain (November 12, 2015). "Tropical Storm Kate Discussion Number 13". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ↑ Todd B. Kimberlain (November 12, 2015). "Tropical Storm Kate Discussion Number 13". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ↑ John L. Beven II (November 12, 2015). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Kate Discussion Number 14". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ↑ "Post Tropical Kate to Bring Flood Risk & Gales This Weekend". Weather Scientific. November 13, 2015. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ↑ "Surface weather showing Ex-Kate". Institut für Meteorologie (in German). The Free University of Berlin. November 16, 2015. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- ↑ "Flooding and fallen trees block roads in Bridgend County as forecasters warn there's more to come". Wales Online (Media Wales Ltd). November 16, 2015. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- ↑ Tropical Cyclone Naming History and Retired Names. National Hurricane Center (Report) (Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). April 11, 2013. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

External links

- National Hurricane Center Website

- National Hurricane Center's Atlantic Tropical Weather Outlook

- Tropical Cyclone Formation Probability Guidance Product

| |||||||||||||

.jpg)