The 2003 Atlantic hurricane season officially began June 1, 2003 and officially ended on November 30, 2003.[1] These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin, although effectively the season extended from April through December due to out of season storm activity.

The 2003 season was tied for the sixth most active season on record.[2] Sixteen tropical storms formed, of which seven became hurricanes; of these, three strengthened into major hurricanes, of which one reached Category 5 strength, the highest categorization for Atlantic hurricanes on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale. The most notable storms of the season were hurricanes Fabian, Isabel, and Juan, all of which were retired.[3] The total season impact resulted in $4.4 billion (2003 USD) in damage and 92 total deaths.

Storms

Tropical Storm Ana

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

April 20 – April 24 |

| Peak intensity |

60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 994 mbar (hPa) |

A non-tropical low pressure area developed about 240 mi (390 km) south-southwest of Bermuda on April 18 through the interaction of an upper-level trough and a surface frontal trough. It tracked northwestward at first, then turned to the southeast. After developing centralized convection, the system developed into Subtropical Storm Ana on April 20 to the west of Bermuda. It tracked east-southeastward and organized, and on April 21 it transitioned into a tropical cyclone with peak winds of 60 mph (95 km/h), after developing an upper-level warm core. Increased wind shear caused fluctuations in intensity and a steady weakening trend, and on April 24 the center of Ana merged with an approaching cold front, thus signaling the completion of extratropical transition. The extratropical remnants continued east-northeastward, and on April 27 the gale was absorbed within the cold front.[4]

The cyclone is most notable for being the only Atlantic tropical cyclone in the month of April. When Ana became a Subtropical Storm, it became the second subtropical cyclone on record in the month, after a storm in 1992.[4] Ana dropped 2.63 in (67 mm) of rainfall in Bermuda over a period of several days.[5] Increased swells from the storm caused two drowning deaths in southeastern Florida when a boat capsized.[4] The remnants of the storm brought light rainfall to the Azores and the United Kingdom, though no significant damage was reported.[6]

Tropical Depression Two

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

June 11 – June 11 |

| Peak intensity |

35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min) 1008 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave moved off the coast of Africa on June 6.[7] Tracking westward at a low latitude, a disturbance along the wave axis became better organized on June 9,[8] with reasonable favorable environmental conditions despite the time of year. Initially lacking a well-defined low-level circulation,[9] convection increased further on June 10, and the system was declared Tropical Depression Two early on June 11 in the central tropical Atlantic Ocean.[7][10] The depression was only the third tropical cyclone on record to develop in the month of June to the east of the Lesser Antilles;[11] the others were Tropical Depression Two in 2000,[12] Ana in 1979, and a Storm in 1933.[11]

Initially, the depression was forecast to attain tropical storm status, maintaining good outflow and some banding features around the system.[10] Around 0900 UTC on June 11 satellite-based intensity estimates indicated the depression was near tropical storm status.[13] However, the convection subsequently diminished and became displaced to the northeast of the center, and late on June 11 the depression degenerated into an open tropical wave about 950 mi (1535 km) east-southeast of Barbados.[7] The tropical wave remained well-defined with a well-defined low-level vorticity, though strong wind shear prevented tropical redevelopment.[14] On June 13 its remnants passed through the Lesser Antilles, and the wave continued westward through the Caribbean Sea.[15]

Tropical Storm Bill

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

June 29 – July 2 |

| Peak intensity |

60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 997 mbar (hPa) |

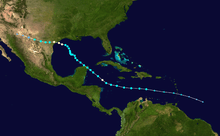

Tropical Storm Bill developed from a tropical wave on June 29 to the north of the Yucatán Peninsula. It slowly organized as it moved northward, and reached a peak of 60 mph (95 km/h) shortly before making landfall 27 mi (43 km) west of Chauvin, Louisiana. Bill quickly weakened over land, and as it accelerated to the northeast, moisture from the storm, combined with cold air from an approaching cold front, produced an outbreak of 34 tornadoes. Bill became extratropical on July 2, and was absorbed by the cold front later that day.[16]

Upon making landfall on Louisiana, the storm produced a moderate storm surge, causing tidal flooding.[17] In a city in the northeastern portion of the state, the surge breached a levee, which flooded many homes in the town.[18] Moderate winds combined with wet soil knocked down trees, which then hit a few houses and power lines,[19] and left hundreds of thousands without electric power.[20] Further inland, tornadoes from the storm produced localized moderate damage. Throughout its path, Tropical Storm Bill caused around $50 million in damage (2003 USD, $64.3 million 2016 USD) and four deaths.[16]

Hurricane Claudette

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

July 8 – July 17 |

| Peak intensity |

90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min) 979 mbar (hPa) |

A well-organized tropical wave tracked quickly through the Lesser Antilles on July 7, producing tropical storm force winds but failing to attain a low-level circulation. After organizing in the Caribbean Sea, it developed into Tropical Storm Claudette to the south of the Dominican Republic on July 8. Its intensity fluctuated over the subsequent days, attaining hurricane status briefly on July 10 before weakening and hitting Puerto Morelos on the Yucatán Peninsula on July 11 as a tropical storm. The storm remained disorganized due to moderate wind shear, though after turning west-northwestward into an area of lighter shear, it re-attained hurricane status on July 15 off the coast of Texas; it intensified quickly and made landfall on Matagorda Island with peak winds of 90 mph (145 km/h). It slowly weakened after moving ashore, tracking across northern Tamaulipas before dissipating in northwestern Chihuahua.[21]

The precursor cyclone caused light damage in the Lesser Antilles, and waves from the hurricane caused an indirect death off of Florida.[21] Widespread flooding and gusty winds destroyed or severely damaged 412 buildings in southeast Texas, with a further 1,346 buildings suffering lighter impact. The hurricane caused locally severe beach erosion along the coast.[22] High winds downed many trees along the coast, causing one direct and one indirect death. Damage was estimated at $180 million (2003 USD, $232 million 2016 USD).[21]

Hurricane Danny

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

July 16 – July 21 |

| Peak intensity |

75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min) 1000 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave moved off the coast of Africa on July 9. The northern portion of the wave tracked to the west-northwest, and on July 13 an area of convection developed along the wave axis. The system slowly organized, and after a closed low-level circulation developed, the system was classified as Tropical Depression Five about 630 mi (1020 km) east of Bermuda. It quickly organized, becoming Tropical Storm Danny a day after forming. Tracking around the periphery of an anticyclone, the storm moved northwestward before turning north and later northeastward. Despite being located at a high latitude, Danny continued to strengthen due to unusually warm water temperatures, and on July 19 it attained hurricane status about 525 mi (850 km) south of St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador.[23]

Wind shear increased the next day as the hurricane turned eastward, causing a steady weakening trend that was accelerated after crossing into an area of cooler water temperatures. By July 20 the cyclone had turned to the southeast and weakened to tropical depression status, and on July 21 it degenerated into a remnant low pressure area. The remnants of Danny tracked erratically southwestward before dissipating on July 27 about 630 mi (1015 km) east of where it originally developed. There were no reports of damages or casualties associated with Danny.[23]

Tropical Depression Six

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

July 19 – July 21 |

| Peak intensity |

35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min) 1010 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave moved westward off the coast of Africa on July 14.[24] After tracking steadily westward, an area of thunderstorms became more concentrated as its upper-level environment became more favorable,[25] and late on July 19 the National Hurricane Center classified it as Tropical Depression Six while it was located about 1035 mi (1675 km) east of the Lesser Antilles.[24] Upon being classified as a tropical cyclone, the depression maintained two ill-defined hooking bands to its north and south, and was originally forecast to attain hurricane status before passing through the Lesser Antilles. With warm waters and very light wind shear forecast, its environmental conditions met four out of five parameters for rapid intensification.[26] Subsequently, convection diminished as the result of cold air inflow and instability from a disturbance to its southeast.[27]

With a fast forward speed, confirmation of a low-level circulation on July 20 became difficult.[28] Convection increased in curvature on July 21,[29] and several islands in the Lesser Antilles issued tropical storm warnings and watches. After it passed north of Barbados, a Hurricane Hunters flight failed to report a closed low-level circulation, and it is estimated the depression degenerated into an open tropical wave late on July 21. The remnants brought a few showers to the Lesser Antilles,[24] and after tracking into the Caribbean Sea redevelopment was prevented by increased wind shear.[30] The northern portion of the wave axis split and developed into Tropical Depression Seven.[24]

Tropical Depression Seven

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

July 25 – July 27 |

| Peak intensity |

35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min) 1016 mbar (hPa) |

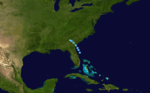

A tropical wave interacted with an upper-level low to develop an area of deep convection near Hispaniola on July 23.[31] A mid- to lower-level circulation developed within the system at it tracked generally north-northwestward, and based on surface and satellite observations, it is estimated the system developed into Tropical Depression Seven at 1200 UTC on July 25 about 60 mi (95 km) east of Daytona Beach, Florida. The system was embedded in an environment characterized by high surface pressures. Tracking through an area of cool water temperatures,[31] as well as unfavorable upper-level winds, the depression failed to achieve winds greater than 35 mph (55 km/h).[32]

Early on July 26 it moved ashore on St. Catherines Island, Georgia, and after steadily weakening over land it dissipated on July 27. As the storm was never forecast to attain tropical storm status, no tropical storm warnings or watches were issued.[31] However, flood watches were posted for much of Georgia and South Carolina.[33] The depression dropped light to moderate rainfall from Florida to the coast of North Carolina, peaking at 5.17 in (131 mm) in Savannah, Georgia. Mostly, rainfall totals between 1 and 3 inches (25 and 76 mm) were common.[34] There were no reports of damage or casualties associated with this depression.[31]

Hurricane Erika

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

August 14 – August 17 |

| Peak intensity |

75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min) 986 mbar (hPa) |

The precursor system to Hurricane Erika was first observed as a non-tropical low on August 9 about 1150 mi (1860 km) east of Bermuda. It tracked quickly southwestward then westward in tandem with an upper-level low, which prevented tropical development. On August 13 an area of convection increased as it passed through the Bahamas, and while crossing Florida a circulation built toward the surface; it is estimated the system developed into Tropical Storm Erika on August 14 about 85 mi (140 km) west-southwest of Fort Myers, Florida. A strong ridge caused the storm to continue quickly westward, and the system gradually strengthened and organized. By August 15 its forward motion slowed, allowing the convection to organize into curved rainbands, and late in the day an eye feature began developing. Tropical Storm Erika attained hurricane status at around 1030 UTC as it was moving ashore in northeastern Tamaulipas; operationally it was not classified as a hurricane, due to lack of data. The winds rapidly decreased as it tracked across the mountainous terrain of northeastern Mexico, and early on August 17 the cyclone dissipated.[35]

The hurricane dropped light to moderate rainfall along its path, which caused some flooding; in Montemorelos in Nuevo León, two people died after being swept away by floodwaters. Several mudslides were reported, which left numerous highways blocked or impassable. In southern Texas, the hurricane caused light winds and minor damage, with no reports of deaths or injuries in the United States.[35]

Tropical Depression Nine

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

August 21 – August 22 |

| Peak intensity |

35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min) 1007 mbar (hPa) |

A strong tropical wave moved off the coast of Africa on August 14,[36] and after tracking steadily westward an area of convection began to become better organized on August 18.[37] After it tracked through the Lesser Antilles, it developed into Tropical Depression Nine on August 21 to the south of Puerto Rico. The depression quickly showed signs of organization, and forecasters predicted the depression to intensify to a strong tropical storm.[38] However, strong southwesterly wind shear unexpectedly became established over the system, and the depression degenerated into a tropical wave late on August 22 to the south of the eastern tip of the Dominican Republic.[36]

The remnants of the depression dropped light to moderate precipitation in the Dominican Republic, which caused flooding and overflown rivers. More than 100 houses were flooded, and some crop damage was reported.[3] The rainfall was welcome in the country, as conditions were dry in the preceding months.[39] Flooding was also reported in eastern Jamaica, though damage there, if any, is unknown.[3]

Hurricane Fabian

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

August 27 – September 8 |

| Peak intensity |

145 mph (230 km/h) (1-min) 939 mbar (hPa) |

On August 25, a tropical wave emerged off the coast of Africa, and two days later developed enough organized convection to develop into Tropical Depression Ten. Tracking through warm waters and low vertical shear, the depression was named Tropical Storm Fabian on August 28. On August 30, the storm intensified into a hurricane, and it quickly strengthened to attain major hurricane status late that day; on September 1 Fabian reached its peak intensity of 145 mph (230 km/h). The hurricane turned to the north and gradually weakened before passing 14 mi (23 km) west of Bermuda on September 5 with winds of 115 mph (180 km/h). The cyclone accelerated northeastward into an environment of unfavorable conditions, becoming an extratropical cyclone on September 8; two days later it merged with another extratropical storm between southern Greenland and Iceland.[40]

Strong waves caused extensive damage to the Bermuda coastline,[3] destroying 10 nests of the endangered Bermuda petrel.[41] The storm surge from the hurricane stranded one vehicle with three police officers and another with a resident on the causeway between St. George's Parish and St. David's Island, later washing both vehicles into Castle Harbour;[42] all four were killed.[40] Strong winds left about 25,000 people without power on the island, and also caused severe damage to vegetation.[3] The strong winds damaged or destroyed the roofs of numerous buildings on Bermuda,[43] Damage on the island totaled $300 million (2003 USD, $386 million 2016 USD). Elsewhere, strong waves from the hurricane killed a surfer in North Carolina and caused three deaths off of Newfoundland when a fishing vessel sank.[40]

Tropical Storm Grace

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

August 30 – September 2 |

| Peak intensity |

40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min) 1007 mbar (hPa) |

A strong tropical wave accompanied with a low pressure system moved off the coast of Africa on August 19. It moved quickly westward, failing to organize significantly, and developed a surface low pressure area on August 29 in the Gulf of Mexico. Convection continued to organize, and the tropical wave developed into Tropical Depression Eleven on August 30 while located 335 mi (540 km) east-southeast of Corpus Christi, Texas. The depression quickly intensified to become Tropical Storm Grace, though further intensification was limited due to a nearby upper-level low. On August 31, Grace moved ashore on Galveston Island, Texas, and it quickly weakened over land. The storm turned northeastward and was absorbed by a cold front over extreme eastern Oklahoma on September 2.[44]

The storm produced light to moderate precipitation from Texas through the eastern United States, peaking at 10.4 in (263 mm) in eastern Texas.[45] Near where it made landfall, Grace produced flooding of low-lying areas and light beach erosion.[46] In Oklahoma and southern Missouri, the remnants of the storm caused localized flooding.[47][48] No deaths were reported, and damage was minimal.[44]

Tropical Storm Henri

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

September 3 – September 8 |

| Peak intensity |

60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 997 mbar (hPa) |

On August 22, a tropical wave moved off the coast of Africa, and it remained disorganized until reaching the eastern Gulf of Mexico on September 1. A tropical disturbance developed into Tropical Depression Twelve on September 3 about 300 mi (480 km) west of Tampa, Florida. It moved eastward and strengthened into Tropical Storm Henri on September 5, and despite strong wind shear it intensified to reach peak winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) later that day. Subsequently it quickly weakened, and it struck the western Florida coast as a tropical depression. On September 8 it degenerated into a remnant low pressure area off the coast of North Carolina,[49] and after moving ashore near Cape Hatteras,[50] it crossed the Mid-Atlantic states and dissipated on September 17 over New England.[51]

Henri was responsible for locally heavy rainfall across Florida, but damage was minimal.[49] The remnants of Henri caused heavy precipitation in Delaware and Pennsylvania, causing $19.6 million in damage (2003 USD; $24.4 million 2016 USD).[52][53] In Delaware, the rainfall caused record-breaking river flooding, with part of the Red Clay Creek experiencing a 500-year flood,[54] and the system left 109,000 residents without power in Pennsylvania.[53] The impacts of the storm were severely compounded the following week by Hurricane Isabel across the region.

Hurricane Isabel

| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

September 6 – September 19 |

| Peak intensity |

165 mph (270 km/h) (1-min) 915 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave moved off the coast of Africa on September 1, which developed into Tropical Depression Thirteen early on September 6 to the southwest of the Cape Verde islands. It quickly intensified into Tropical Storm Isabel,[55] and it continued to gradually intensify within an area of light wind shear and warm waters.[56] Isabel strengthened to a hurricane on September 7, and the following day it attained major hurricane status. Its intensity fluctuated over the subsequent days as it passed north of the Lesser Antilles, and it attained peak winds of 165 mph (270 km/h) on September 11, a Category 5 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Scale. The hurricane oscillated between Category 4 and Category 5 status over the following four days, before weakening due to wind shear. On September 18 Isabel made landfall between Cape Lookout and Ocracoke Island in North Carolina with winds of 105 mph (165 km/h). It continued northwestward, becoming extratropical over western Pennsylvania before being absorbed by a larger storm over Ontario on September 19.[55]

Strong winds from Isabel extended from North Carolina to New England and westward to West Virginia. The winds, combined with previous rainfall which moistened the soil, downed many trees and power lines across its path, leaving about 6 million electricity customers without power at some point. Coastal areas suffered from waves and its powerful storm surge, with areas in eastern North Carolina and southeast Virginia reporting severe damage from both winds and the storm surge. Throughout its path, Isabel resulted in $3.6 billion in damage (2003 USD; $4.63 billion 2016 USD) and 47 deaths, of which 16 were directly related to the storm's effects.[57]

The governors of Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Maryland, New Jersey, and Delaware declared states of emergencies.[58] Isabel was the first major hurricane to threaten the Mid-Atlantic States and the South since Hurricane Floyd in September 1999. Isabel's greatest impact was due to flood damage, the worst in some areas of Virginia since 1972's Hurricane Agnes. More than 60 million people were affected to some degree — a similar number to Floyd but more than any other hurricane in recent memory.[59]

Tropical Depression Fourteen

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

September 8 – September 10 |

| Peak intensity |

35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min) 1007 mbar (hPa) |

A strong tropical wave moved off the coast of Africa on September 6, and almost immediately it became associated with a broad surface circulation.[60] With favorable upper-level winds the system quickly became better organized,[61] and on September 8 it possessed enough organization to be classified as Tropical Depression Fourteen while located about 290 mi (465 km) southeast of the southernmost Cape Verde islands.[60] Initially the depression failed to maintain an inner core of deep convection, and despite its occurrence with nearby dry air, the depression was forecast to intensify to hurricane status due to anticipated favorable conditions.[62]

In the hours subsequent to formation, the convection near the center decreased as the banding features dissipated.[63] Dry air greatly increased over the depression, and by September 9 the system was not forecast to intensify past minimal tropical storm status.[64] Later that day an upper-level low tracked southward to the west of the depression, which increased wind shear and caused a steady north-northwest motion for the depression. The circulation became elongated and separated from the convection as it passed just west of the Cape Verde Islands,[60] where it brought heavy rainfall,[65] and on September 10 the depression dissipated.[60]

Hurricane Juan

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

September 24 – September 29 |

| Peak intensity |

105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min) 969 mbar (hPa) |

Main article:

Hurricane JuanA large tropical wave moved off the coast of Africa on September 14,[66] and due to unfavorable wind shear it initially remained disorganized.[67] An area of convection increased in association with an upper-level low, and it developed into Tropical Depression Fifteen on September 24 to the southeast of Bermuda. It steadily organized as it tracked northward, intensifying into Tropical Storm Juan on September 25 and attaining hurricane status on September 26.[66] With warm waters and light wind shear, Juan reached peak winds of 105 mph (165 km/h) on September 27 about 635 mi (1,020 km) south of Halifax, Nova Scotia.[68] It accelerated northward, weakening only slightly before moving ashore near Halifax on September 29 with winds of 100 mph (160 km/h). It quickly weakened while crossing the southern Canadian Maritimes before being absorbed by a large extratropical cyclone over the Gulf of Saint Lawrence.[66]

The eyewall of Hurricane Juan was the first to directly cross over Halifax since a hurricane in August of 1893; the cyclone became one of the most damaging tropical cyclones in modern history for the city. The hurricane produced a record storm surge of 4.9 ft (1.5 m), which resulted in extensive flooding of the Halifax and Dartmouth waterfront properties. Strong winds caused widespread occurrences of falling trees, downed power lines, and damaged houses, and the hurricane was responsible for four direct deaths and four indirect deaths.[66] More than 800,000 people were left without power. Nearly all wind-related damage occurred to the east of the storm track, and damage amounted to about $200 million (2003 CAD; $150 million 2003 USD; $257 million 2016 USD).[69]

Hurricane Kate

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

September 25 – October 7 |

| Peak intensity |

125 mph (205 km/h) (1-min) 952 mbar (hPa) |

Kate developed from a tropical wave in the central tropical Atlantic on September 25. The storm moved northwestward until a weakness in the subtropical ridge forced it eastward. Kate strengthened to a hurricane, turned sharply westward while moving around a mid-level low, and intensified to a 125 mph (205 km/h) major hurricane on October 4. Kate turned sharply northward around the periphery of an anticyclone, weakened, and became extratropical after passing to the east of Newfoundland. The extratropical storm persisted for three days until losing its identity near Scandinavia.[70]

Kate threatened Atlantic Canada just one week after Hurricane Juan caused severe damage in Nova Scotia. The storm had minimal effects on land, limited to moderately strong winds and heavy rainfall over Newfoundland;[71] St. John's reported 1.8 in (45 mm) on October 6, a record for the date.[72] The interaction between Kate and a high pressure area to its north produced three to four ft (one m) waves along the coast of North Carolina and New England.[73]

Tropical Storm Larry

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

October 1 – October 6 |

| Peak intensity |

65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) 993 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave moved off the coast of Africa on September 17, which developed a low pressure area on September 27 in the western Caribbean Sea. It moved ashore along the Yucatán Peninsula on September 29 and developed into an extratropical cyclone as it interacted with a stationary cold front. Deep convection increased, and it transitioned into Tropical Storm Larry by October 1. The storm drifted generally southward, and after reaching peak winds of 65 mph (100 km/h) it made landfall in the Mexican state of Tabasco on October 5,[74] the first landfall in the state since Hurricane Brenda in 1973.[75] The remnants of Larry crossed the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, degenerating into a remnant low pressure area before dissipating on October 7 in the eastern Pacific Ocean.[74]

The storm dropped heavy rainfall, peaking at 24.77 inches (629.2 mm) in Upper Juarez in southeastern Mexico.[76] The rainfall caused mudslides and damage, which coincided with the presence of two other tropical cyclones – Eastern Pacific tropical storm Nora and Olaf.[77] Overall, the storm resulted in five deaths and $53.4 million in damage (2003 USD).[74][78]

Tropical Storm Mindy

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

October 10 – October 14 |

| Peak intensity |

45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1002 mbar (hPa) |

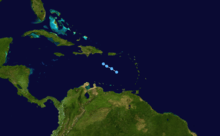

A tropical wave exited the coast of Africa on October 1 and moved westward.[79] On October 8, thunderstorms spread across the Lesser Antilles, and the wave slowly organized.[80] Rainfall reached 2.98 in (75 mm) in Christiansted in Saint Croix, and 7.13 in (181 mm) near Ponce, Puerto Rico.[45] Strong winds left around 29,000 people without power in northeastern Puerto Rico.[81] The rainfall wrecked bridges in Las Piedras and Guayama,[82][83] and led to flooded streams, downed trees, and rockslides that closed four roads. One car was swept away,[84] and a few houses were flooded.[85] The damage total was at least $46,000 (2003 USD).[82][83][86]

It turned northwestward through a weakness in the subtropical ridge, and despite strong wind shear developed into Tropical Storm Mindy late on October 10 over eastern Dominican Republic, with peak winds of 45 mph (75 km/h).[79] It produced 2.63 in (60 mm) of rain in Santiago Rodríguez, which caused flooding and damaged 320 houses.[87] Although forecast to intensify to 65 mph (105 km/h) winds, the storm weakened due to the wind shear.[88] The center passed near the Turks and Caicos Islands on October 11,[79] and winds reached only 31 mph (50 km/h) at Grand Turk Island.[87] On October 12, Mindy weakened to a tropical depression, and later turned eastward due to an approaching short-wave trough. Devoid of deep convection, the circulation dissipated on October 14 about 445 mi (715 km) south-southwest of Bermuda.[79] Mindy produced two to three ft (0.6 to 0.9 m) swells along the U.S. Atlantic coast from Florida through North Carolina.[73]

Tropical Storm Nicholas

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

October 13 – October 23 |

| Peak intensity |

70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) 990 mbar (hPa) |

Forming from a tropical wave on October 13 in the central tropical Atlantic Ocean, Nicholas slowly developed due to moderate levels of wind shear throughout its lifetime. Deep convection slowly organized, and Nicholas attained a peak intensity of 70 mph (110 km/h) on October 17. After moving west-northwestward for much of its lifetime, it turned northward and weakened due to increasing shear. The storm again turned to the west and briefly restrengthened, but after turning again to the north Nicholas transitioned to an extratropical cyclone on October 24. As an extratropical storm, Nicholas executed a large loop to the west, and after moving erratically for a week and organizing into a tropical low, it was absorbed by a non-tropical low. The low continued westward, crossed Florida, and ultimately dissipated over the Gulf Coast of the United States on November 5.[89]

Nicholas had no impact as a tropical cyclone, and impact from the low that absorbed the storm was limited to rainfall, gusty winds, and rough surf.[73] The low that absorbed the storm nearly developed into a tropical cyclone, which would have been called Odette. However, moderate wind shear prevented further development.[90]

Tropical Storm Odette

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

December 4 – December 7 |

| Peak intensity |

65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) 993 mbar (hPa) |

Odette was a rare December tropical storm, the first since Hurricane Lili in 1984, that formed on December 4 in the southwest Caribbean Sea. Odette strengthened and made landfall near Cabo Falso in the Dominican Republic on December 6 as a moderately strong tropical storm. A day later, Odette became extratropical, and eventually merged with a cold front.[91]

Eight deaths were directly attributed to this tropical storm in the Dominican Republic due to mudslides or flash flooding. In addition, two deaths were indirectly caused by the storm. Approximately 35% of the nation's banana crop was destroyed.[91] Light to moderate rainfall was reported in Puerto Rico.[51]

Tropical Storm Peter

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) |

|

|

| Duration |

December 7 – December 11 |

| Peak intensity |

70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) 990 mbar (hPa) |

By December 5, an extratropical cyclone developed and was moving southward, isolated from the Westerlies. Convection developed near the center, and the system organized into a subtropical storm late on December 7, about 835 mi (1340 km) south-southwest of the Azores. The system moved southwestward over warmer waters, and deep convection continued to organize over the center. Banding features also increased, and the National Hurricane Center declared the system as Tropical Storm Peter on December 9, about 980 mi (1580 km) northwest of the Cape Verde islands. With the development of Peter and Odette, 2003 became the first year since 1887 that two storms developed in the month of December.[92] Peter also made 2003 the eighth most active season on record, and is one of only seven storms to reach the "P" name since naming began in 1950.[2]

Initially, the National Hurricane Center did not anticipate strengthening;[93] however, Peter intensified to winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) late on December 9, after an eye feature developed. Usually that would indicate hurricane intensity, but as the eye was short-lived, Peter remained a tropical storm. It turned northward ahead of the same frontal system that absorbed Tropical Storm Odette, and the combination of strong upper-level winds and cooler water temperatures caused quick weakening. By December 10, Peter degenerated into a tropical depression, and after turning northeastward it was absorbed by the cold front the next day.[92]

Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) Ranking

The table on the right shows the ACE for each storm in the season. The ACE is, broadly speaking, a measure of the power of the hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed for, so hurricanes that lasted a long time (such as Isabel and Fabian) have higher ACEs. Isabel was one of the very few hurricanes since 1950 to have an ACE of over 50 104 kt2, and was one of just 7 to have an ACE of over 60.[2]

See also

References

- ↑ Jack Beven (2003). "June 1 Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

- 1 2 3 National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division (February 17, 2016). "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 World Meteorological Organization (2004). "Final Report of the Twenty-Sixth Session" (DOC). Retrieved 2006-06-03.

- 1 2 3 Beven, Jack (December 19, 2003). "Tropical Storm Ana Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ "Bermuda Weather for April 2003". Bermuda Weather Service. May 25, 2003. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ Padgett, Gary (2003). "April 2003 Global Tropical Cyclone Summary". Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- 1 2 3 Franklin, James (August 6, 2003). "Tropical Depression Two Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ Lawrence, Miles (June 9, 2003). "June 9 Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ Franklin, James (June 9, 2003). "June 9 Tropical Weather Outlook (2)". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- 1 2 Avila, Lixion (June 11, 2003). "Tropical Depression Two Discussion One". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- 1 2 Pasch, Richard / Stewart, Stacy / Lawrence, Miles (July 1, 2003). "June 2003 Tropical Weather Summary". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ Padgett, Gary (2000). "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary June 2000". Australia Severe Weather. Retrieved 2012-02-03.

- ↑ Pasch, Richard (June 11, 2003). "Tropical Depression Two Discussion Two". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ Formosa, Mike (June 13, 2003). "June 13 Tropical Weather Discussion". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ Avila, Lixion (June 13, 2003). "June 13 Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- 1 2 Avila, lixion (December 8, 2003). "Tropical Storm Bill Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ National Climatic Data Center (August 2, 2003). "Event Report for Louisiana". Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ National Climatic Data Center (August 2, 2003). "Event Report for Louisiana (2)". Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ New Orleans National Weather Service (October 9, 2003). "Tropical Storm Bill Post Tropical Cyclone Report". Archived from the original on 2006-09-30. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ "Gulf Coast reeling from Tropical Storm Bill". USA Today. June 30, 2003. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- 1 2 3 Beven, Jack (September 9, 2003). "Hurricane Claudette Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ National Weather Service at Houston/Galveston (2003). "Upper Texas Coast Tropical Cyclones in the 2000s". Archived from the original on January 11, 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

- 1 2 Stewart, Stacy. "Hurricane Danny Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- 1 2 3 4 Lawrence, Miles (August 18, 2003). "Tropical Depression Six Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ Avila, Lixion (July 19, 2003). "July 19 Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-12.

- ↑ Avila, Lixion (July 19, 2003). "Tropical Depression Six Discussion One". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ Stewart, Stacy (June 20, 2003). "Tropical Depression Six Discussion Three". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ Lawrence, Miles (July 20, 2003). "Tropical Depression Six Discussion Four". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ Beven, Jack (July 21, 2003). "Tropical Depression Six Discussion Six". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ Stewart, Stacy (July 22, 2003). "July 22 Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- 1 2 3 4 Pasch, Richard (November 30, 2003). "Tropical Depression Seven Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ Avila, Lixion (July 25, 2003). "Tropical Depression Seven Discussion One". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ "Saturday: No. 7 Unlucky For Soggy Georgia, SC". WJXT. July 26, 2003. Archived from the original on 2011-05-24. Retrieved 2011-12-30.

- ↑ Roth, David (August 4, 2008). "Tropical Depression #7 - July 25-27, 2003". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- 1 2 Franklin, James (November 13, 2003). "Hurricane Erika Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- 1 2 Avila, Lixion (November 17, 2003). "Tropical Depression Nine Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ Stewart, Stacy (August 18, 2003). "August 18 Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ Avila, Lixion (August 21, 2003). "Tropical Depression Nine Discussion One". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ Stormcarib.net (2003). "Unofficial Reports from the Dominican Republic". Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- 1 2 3 Pasch, Blake, & Brown (2003). "Hurricane Fabian Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-12-17.

- ↑ Environment News Service (2003). "Bermuda's National Bird Blown Away". Retrieved 2006-10-17.

- ↑ Karen Smith and Dan Rutstein (2003-09-06). "Search for the missing a difficult job". The Royal Gazette. Retrieved 2008-01-03.

- ↑ The Royal Gazette (2003-09-06). "Bermuda Shorts — Fabian". Retrieved 2008-02-03.

- 1 2 Stewart, Stacy (November 27, 2003). "Tropical Storm Grace Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-12-22.

- 1 2 Hydrometeorological Prediction Center (2005). "Rainfall data for Tropical Storm Grace". Retrieved 2007-12-17.

- ↑ Jim O'Donnel (2003). "Tropical Storm Grace Preliminary Storm Report". Jamaica Beach Weather Observatory. Retrieved 2006-08-14.

- ↑ Ty Judd (2003). "The 2003 Labor Day Weekend Heavy Rain and Flooding Event". Norman, Oklahoma National Weather Service. Archived from the original on 2006-06-04. Retrieved 2006-08-18.

- ↑ Paducah, Kentucky National Weather Service (2003). "Autumn 2003 Weather Summary". Retrieved 2006-08-18.

- 1 2 Daniel P. Brown and Miles Lawrence (2003). "Tropical Storm Henri Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- ↑ James L. Franklin (2003). "Tropical Weather Outlook for September 12, 2003". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-12-19.

- 1 2 David Roth (2006). "Rainfall information on Tropical Storm Henri". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- ↑ National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Delaware". Retrieved 2007-12-19.

- 1 2 National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Pennsylvania". Retrieved 2007-12-19.

- ↑ Stefanie Baxter (2003). "Henri Visits Delaware" (PDF). Delaware Geological Survey. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- 1 2 Jack Beven & Hugh Cobb (January 16, 2004). "Hurricane Isabel Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- ↑ Avila, Lixion (September 6, 2003). "Tropical Storm Isabel Discussion Two". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- ↑ United States Department of Commerce (2004). "Service Assessment of Hurricane Isabel" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- ↑ Scotsman.com (September 19, 2003). "America feels the wrath of Isabel". The Scotsman (Edinburgh). Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- ↑ National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Climate of 2003- Comparison of Hurricanes Floyd, Hugo and Isabel". Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- 1 2 3 4 Franklin, James (September 11, 2003). "Tropical Depression Fourteen Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ Stewart, Stacy (September 7, 2003). "September 7 Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ Stewart, Stacy (September 8, 2003). "Tropical Depression Fourteen Discussion One". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ Stewart, Stacy (September 8, 2003). "Tropical Depression Fourteen Discussion Two". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ↑ Knabb, Richard & Franklin, James (September 9, 2003). "Tropical Depression Fourteen Discussion Three". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ Avila, Lixion (September 10, 2003). "Tropical Depression Fourteen Public Advisory Eight". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- 1 2 3 4 Avila, Lixion (May 12, 2004). "Hurricane Juan Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- ↑ Avila, Lixion (September 17, 2003). "September 17 Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- ↑ Avila, Lixion (September 27, 2003). "Hurricane Juan Discussion Ten". NHC. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ↑ Fogarty, Chris (2003). "Hurricane Juan Storm Summary" (PDF). Canadian Hurricane Centre/Environment Canada. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- ↑ Pasch, Richard / Molleda, Robert (November 30, 2003). "Hurricane Kate Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ Rousell, Guy / Bowyer, Peter (October 6, 2003). "Canadian Hurricane Information Statement at 9:30 AM NDT Monday October 6, 2003". Canadian Hurricane Centre. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ CBC news (October 7, 2003). "Lots of rain, but no flooding from Kate". CBC News. Retrieved 2006-10-04.

- 1 2 3 Sean Collins (2003). "Wavetraks October Newsletter". Surfline Forecast Team. Retrieved 2006-10-09.

- 1 2 3 Stacy Stuart (2003). "Tropical Storm Larry Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2006-06-03.

- ↑ Servicio Meteorológico Nacional (2003). "Tormenta Tropical "Larry" del Océano Atlántico" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2005-12-29. Retrieved 2006-06-03.

- ↑ David Roth (2006). "Rainfall data for Tropical Storm Larry". wpc. Retrieved 2006-09-21.

- ↑ Associated Press (2003). "Tropical Depression Olaf weakens after moving inland". Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved 2006-06-03.

- ↑ Foro Consultivo Cientifico y Technológio (2005). "Desastres mayores registrados en México de 1980 a 2003" (PDF) (in Spanish). Retrieved 2006-06-03.

- 1 2 3 4 Lawrence, Miles (2003). "Tropical Storm Mindy Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ Beven, Jack (October 8, 2003). "October 8 Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2006-10-09.

- ↑ National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Puerto Rico (6)". Retrieved 2006-10-09.

- 1 2 National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Puerto Rico (8)". Retrieved 2006-10-09.

- 1 2 National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Puerto Rico (12)". Retrieved 2006-10-09.

- ↑ National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Puerto Rico (3)". Retrieved 2006-10-09.

- ↑ National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Puerto Rico (4)". Retrieved 2006-10-09.

- ↑ National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Puerto Rico (11)". Retrieved 2006-10-09.

- 1 2 World Meteorological Organization (2004). "Final Report of the 2003 Hurricane Season" (PDF). Retrieved 2006-10-09.

- ↑ Beven (2003). "Tropical Storm Mindy Discussion Two". NHC. Retrieved 2006-10-09.

- ↑ Beven, Jack (January 7, 2004). "Tropical Storm Nicholas Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ Padgett, Gary (2003). "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary - November 2003". Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- 1 2 Franklin, James (December 19, 2003). "Tropical Storm Odette Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- 1 2 Avila, Lixion (December 17, 2003). "Tropical Storm Peter Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ↑ Avila, Lixion (December 7, 2003). "Tropical Storm Peter Discussion One". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

External links

|

|---|

| | | |

-

Book Book

-

Category Category

-

Portal Portal

-

WikiProject WikiProject

-

Commons Commons

|

|

.jpg)