Tropics

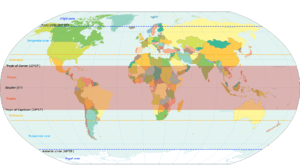

The tropics is a region of the Earth surrounding the Equator. It is limited in latitude by the Tropic of Cancer in the Northern Hemisphere at 23°26′13.9″ (or 23.4372°) N and the Tropic of Capricorn in the Southern Hemisphere at 23°26′13.9″ (or 23.4372°) S; these latitudes correspond to the axial tilt of the Earth. The tropics are also referred to as the tropical zone and the torrid zone (see geographical zone). The tropics include all the areas on the Earth where the Sun reaches a subsolar point, a point directly overhead at least once during the solar year.

The tropics are distinguished from the other climatic and biomatic regions of Earth, the middle latitudes and the polar regions on either side of the equatorial zone.

Seasons and climate

"Tropical" is sometimes used in a general sense for a tropical climate to mean warm to hot and moist year-round, often with the sense of lush vegetation.

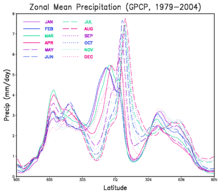

Many tropical areas have a dry and wet season. The wet season, rainy season or green season, is the time of year, ranging from one or more months, when most of the average annual rainfall in a region falls.[1] Areas with wet seasons are disseminated across portions of the tropics and subtropics.[2] Under the Köppen climate classification, for tropical climates, a wet season month is defined as a month where average precipitation is 60 millimetres (2.4 in) or more.[3] Tropical rainforests technically do not have dry or wet seasons, since their rainfall is equally distributed through the year.[4] Some areas with pronounced rainy seasons see a break in rainfall during mid-season when the intertropical convergence zone or monsoon trough moves poleward of their location during the middle of the warm season.[5]

When the wet season occurs during the warm season, or summer, precipitation falls mainly during the late afternoon and early evening hours. The wet season is a time when air quality improves, freshwater quality improves and vegetation grows significantly, leading to crop yields late in the season. Floods cause rivers to overflow their banks, and some animals to retreat to higher ground. Soil nutrients diminish and erosion increases. The incidence of malaria increases in areas where the rainy season coincides with high temperatures. Animals have adaptation and survival strategies for the wetter regime. Unfortunately, the previous dry season leads to food shortages into the wet season, as the crops have yet to mature.

Regions within the tropics may well not have a tropical climate. There are alpine tundra and snow-capped peaks, including Mauna Kea, Mount Kilimanjaro, and the Andes as far south as the northernmost parts of Chile and Argentina. Under the Köppen climate classification, much of the area within the geographical tropics is classed not as "tropical" but as "dry" (arid or semi-arid) including the Sahara Desert, the Atacama Desert and Australian Outback.

Tropical ecosystems

Tropical plants and animals are those species native to the tropics. Tropical ecosystems may consist of rainforests, dry deciduous forests, spiny forests, desert and other habitat types. There are often significant areas of biodiversity, and species endemism present, particularly in rainforests and dry deciduous forests. Some examples of important biodiversity and/or high endemism ecosystems are: El Yunque National Forest in Puerto Rico, Costa Rican and Nicaraguan rainforests, Amazon Rainforest territories of several South American countries, Madagascar dry deciduous forests, the Waterberg Biosphere of South Africa, and eastern Madagascar rainforests. Often the soils of tropical forests are low in nutrient content, making them quite vulnerable to slash-and-burn deforestation techniques, which are sometimes an element of shifting cultivation agricultural systems.

In biogeography, the tropics are divided into Paleotropics (Africa, Asia and Australia) and Neotropics (Caribbean, Central America, and South America). Together, they are sometimes referred to as the Pantropic. The Neotropical region should not be confused with the ecozone of the same name; in the Old World, there is no such ambiguity, as the Paleotropics correspond to the Afrotropical, Indomalayan, and partly the Australasian and Oceanic ecozones.

Tropicality

Tropicality can be described as the idea or imagination that Western geographers held about the tropics. The idea of Tropicality gained renewed interest in modern geographical discourse when French geographer Pierre Gourou published Les Pays Tropicaux, in English, The Tropical World, in the late 1940s.[6]

There are two major imaginations of the tropics which are presented through Tropicality. The first imagination is that the tropics are a sort of Garden of Eden, a heaven on Earth.[7] The second imagination is that tropic areas are primitive and essentially lawless.[7] The second imagination of the tropics was often discussed in Western literature, more so than the first imagination.

Western scholars also theorized about the possible reasons why tropical areas were inferior to northern areas. A popular explanation was the difference in climate between northern and tropical regions. Tropical regions typically have much warmer weather than northern areas, leading some scholars, such as Gourou and other western scholars, to theorize that there is a correlation between warmer climates and primitive indigenous populations lacking a control over nature whereas northern populations had mastered nature.[8]

Image gallery

-

A Morpho peleides (Blue Morpho) tropical butterfly

-

A Graphium agamemnon (Tailed Jay) belongs to the swallowtail family.

See also

References

- ↑ Glossary of Meteorology (2009). Rainy season. American Meteorological Society. Retrieved on 2008-12-27.

- ↑ Michael Pidwirny (2008). CHAPTER 9: Introduction to the Biosphere. PhysicalGeography.net. Retrieved on 2008-12-27.

- ↑ "Updated world Koppen-Geiger climate classification map" (PDF).

- ↑ Elisabeth M. Benders-Hyde (2003). World Climates. Blue Planet Biomes. Retrieved on 2008-12-27.

- ↑ J . S. 0guntoyinbo and F. 0. Akintola (1983). Rainstorm characteristics affecting water availability for agriculture. IAHS Publication Number 140. Retrieved on 2008-12-27.

- ↑ Arnold, David. "Illusory Riches: Representations of the Tropical World, 1840-1950", p. 6. Journal of Tropical Geography

- 1 2 Arnold, David. "Illusory Riches: Representations of the Tropical World, 1840-1950", p. 7. Journal of Tropical Geography

- ↑ Arnold, David. "Illusory Riches: Representations of the Tropical World, 1840-1950", p. 13. Journal of Tropical Geography

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tropics. |

- Tropen, Goethe-Institut http://wayback.archive.org/web/20150311063809/http://www.goethe.de/tropen (bilingual web site English/German with a lot of information and extracts from novels, short stories, essays, etc. written by explorers, conquerors and writers since the discovery of the so-called New World)

|