Trojan War

In Greek mythology, the Trojan War was waged against the city of Troy by the Achaeans (Greeks) after Paris of Troy took Helen from her husband Menelaus, king of Sparta. The war is one of the most important events in Greek mythology and has been narrated through many works of Greek literature, most notably through Homer's Iliad. The Iliad relates a part of the last year of the siege of Troy; the Odyssey describes the journey home of Odysseus, one of the war's heroes. Other parts of the war are described in a cycle of epic poems, which have survived through fragments. Episodes from the war provided material for Greek tragedy and other works of Greek literature, and for Roman poets including Virgil and Ovid.

The war originated from a quarrel between the goddesses Athena, Hera, and Aphrodite, after Eris, the goddess of strife and discord, gave them a golden apple, sometimes known as the Apple of Discord, marked "for the fairest". Zeus sent the goddesses to Paris, who judged that Aphrodite, as the "fairest", should receive the apple. In exchange, Aphrodite made Helen, the most beautiful of all women and wife of Menelaus, fall in love with Paris, who took her to Troy. Agamemnon, king of Mycenae and the brother of Helen's husband Menelaus, led an expedition of Achaean troops to Troy and besieged the city for ten years because of Paris' insult. After the deaths of many heroes, including the Achaeans Achilles and Ajax, and the Trojans Hector and Paris, the city fell to the ruse of the Trojan Horse. The Achaeans slaughtered the Trojans (except for some of the women and children whom they kept or sold as slaves) and desecrated the temples, thus earning the gods' wrath. Few of the Achaeans returned safely to their homes and many founded colonies in distant shores. The Romans later traced their origin to Aeneas, one of the Trojans, who was said to have led the surviving Trojans to modern-day Italy.

The ancient Greeks treated the Trojan War as a historical event that had taken place in the 13th or 12th century BC and believed that Troy was located near the Dardanelles in what is now Turkey. As of the mid-19th century, both the war and the city were widely believed to be non-historical. In 1868, however, the German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann met Frank Calvert, who convinced Schliemann that Troy was at Hissarlik and Schliemann took over Calvert's excavations on property belonging to Calvert;[1] this claim is now accepted by most scholars.[2][3] Whether there is any historical reality behind the Trojan War is an open question. Many scholars believe that there is a historical core to the tale, though this may simply mean that the Homeric stories are a fusion of various tales of sieges and expeditions by Mycenaean Greeks during the Bronze Age. Those who believe that the stories of the Trojan War are derived from a specific historical conflict usually date it to the 12th or 11th centuries BC, often preferring the dates given by Eratosthenes, 1194–1184 BC, which roughly corresponds with archaeological evidence of a catastrophic burning of Troy VIIa.[4]

Sources

The events of the Trojan War are found in many works of Greek literature and depicted in numerous works of Greek art. There is no single, authoritative text which tells the entire events of the war. Instead, the story is assembled from a variety of sources, some of which report contradictory versions of the events. The most important literary sources are the two epic poems traditionally credited to Homer, the Iliad and the Odyssey, composed sometime between the 9th and 6th centuries BC.[5] Each poem narrates only a part of the war. The Iliad covers a short period in the last year of the siege of Troy, while the Odyssey concerns Odysseus's return to his home island of Ithaca, following the sack of Troy.

Other parts of the Trojan War were told in the poems of the Epic Cycle, also known as the Cyclic Epics: the Cypria, Aethiopis, Little Iliad, Iliou Persis, Nostoi, and Telegony. Though these poems survive only in fragments, their content is known from a summary included in Proclus' Chrestomathy.[6] The authorship of the Cyclic Epics is uncertain. It is generally thought that the poems were written down in the 7th and 6th century BC, after the composition of the Homeric poems, though it is widely believed that they were based on earlier traditions.[7] Both the Homeric epics and the Epic Cycle take origin from oral tradition. Even after the composition of the Iliad, Odyssey, and the Cyclic Epics, the myths of the Trojan War were passed on orally, in many genres of poetry and through non-poetic storytelling. Events and details of the story that are only found in later authors may have been passed on through oral tradition and could be as old as the Homeric poems. Visual art, such as vase-painting, was another medium in which myths of the Trojan War circulated.[8]

In later ages playwrights, historians, and other intellectuals would create works inspired by the Trojan War. The three great tragedians of Athens, Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, wrote many dramas that portray episodes from the Trojan War. Among Roman writers the most important is the 1st century BC poet Virgil. In Book 2 of the Aeneid, Aeneas narrates the sack of Troy; this section of the poem is thought to rely on material from the Cyclic Epic Iliou Persis.

Legend

The following summary of the Trojan War follows the order of events as given in Proclus' summary, along with the Iliad, Odyssey, and Aeneid, supplemented with details drawn from other authors.

Origins of the war

The plan of Zeus

According to Greek mythology, Zeus had become king of the gods by overthrowing his father Cronus; Cronus in turn had overthrown his father Uranus. Zeus was not faithful to his wife and sister Hera, and had many relationships from which many children were born. Since Zeus believed that there were too many people populating the earth, he envisioned Momus[9] or Themis,[10] who was to use the Trojan War as a means to depopulate the Earth, especially of his demigod descendants.[11]

The Judgement of Paris

Zeus came to learn from either Themis[12] or Prometheus, after Heracles had released him from Caucasus,[13] that, like his father Cronus, one of his sons would overthrow him. Another prophecy stated that a son of the sea-nymph Thetis, with whom Zeus fell in love after gazing upon her in the oceans off the Greek coast, would become greater than his father.[14] Possibly for one or both of these reasons,[15] Thetis was betrothed to an elderly human king, Peleus son of Aiakos, either upon Zeus' orders,[16] or because she wished to please Hera, who had raised her.[17]

All of the gods were invited to Peleus and Thetis' wedding and brought many gifts,[18] except Eris (the goddess of discord), who was stopped at the door by Hermes, on Zeus' order.[19] Insulted, she threw from the door a gift of her own:[20] a golden apple (το μήλον της έριδος) on which was inscribed the word καλλίστῃ Kallistēi ("To the fairest").[21] The apple was claimed by Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite. They quarreled bitterly over it, and none of the other gods would venture an opinion favoring one, for fear of earning the enmity of the other two. Eventually, Zeus ordered Hermes to lead the three goddesses to Paris, a prince of Troy, who, unaware of his ancestry, was being raised as a shepherd in Mount Ida,[22] because of a prophecy that he would be the downfall of Troy.[23] After bathing in the spring of Ida, the goddesses appeared to him naked, either for the sake of winning or at Paris' request. Paris was unable to decide between them, so the goddesses resorted to bribes. Athena offered Paris wisdom, skill in battle, and the abilities of the greatest warriors; Hera offered him political power and control of all of Asia; and Aphrodite offered him the love of the most beautiful woman in the world, Helen of Sparta. Paris awarded the apple to Aphrodite, and, after several adventures, returned to Troy, where he was recognized by his royal family.

Peleus and Thetis bore a son, whom they named Achilles. It was foretold that he would either die of old age after an uneventful life, or die young in a battlefield and gain immortality through poetry.[24] Furthermore, when Achilles was nine years old, Calchas had prophesied that Troy could not again fall without his help.[25] A number of sources credit Thetis with attempting to make Achilles immortal when he was an infant. Some of these state that she held him over fire every night to burn away his mortal parts and rubbed him with ambrosia during the day, but Peleus discovered her actions and stopped her.[26] According to some versions of this story, Thetis had already destroyed several sons in this manner, and Peleus' action therefore saved his son's life.[27] Other sources state that Thetis bathed Achilles in the River Styx, the river that runs to the under world, making him invulnerable wherever he had touched the water.[28] Because she had held him by the heel, it was not immersed during the bathing and thus the heel remained mortal and vulnerable to injury (hence the expression "Achilles heel" for an isolated weakness). He grew up to be the greatest of all mortal warriors. After Calchas' prophesy, Thetis hid Achilles in Skyros at the court of king Lycomedes, where he was disguised as a girl.[29] At a crucial point in the war, she assists her son by providing weapons divinely forged by Hephaestus (see below).

Elopement of Paris and Helen

The most beautiful woman in the world was Helen, one of the daughters of Tyndareus, King of Sparta. Her mother was Leda, who had been either raped or seduced by Zeus in the form of a swan.[30] Accounts differ over which of Leda's four children, two pairs of twins, were fathered by Zeus and which by Tyndareus. However, Helen is usually credited as Zeus' daughter,[31] and sometimes Nemesis is credited as her mother.[32] Helen had scores of suitors, and her father was unwilling to choose one for fear the others would retaliate violently.

Finally, one of the suitors, Odysseus of Ithaca, proposed a plan to solve the dilemma. In exchange for Tyndareus' support of his own suit towards Penelope,[33] he suggested that Tyndareus require all of Helen's suitors to promise that they would defend the marriage of Helen, regardless of whom he chose. The suitors duly swore the required oath on the severed pieces of a horse, although not without a certain amount of grumbling.[34]

Tyndareus chose Menelaus. Menelaus was a political choice on her father's part. He had wealth and power. He had humbly not petitioned for her himself, but instead sent his brother Agamemnon on his behalf. He had promised Aphrodite a hecatomb, a sacrifice of 100 oxen, if he won Helen, but forgot about it and earned her wrath.[35] Menelaus inherited Tyndareus' throne of Sparta with Helen as his queen when her brothers, Castor and Pollux, became gods,[36] and when Agamemnon married Helen's sister Clytemnestra and took back the throne of Mycenae.[37]

Paris, under the guise of a supposed diplomatic mission, went to Sparta to get Helen and bring her back to Troy. Before Helen could look up to see him enter the palace, she was shot with an arrow from Eros, otherwise known as Cupid, and fell in love with Paris when she saw him, as promised by Aphrodite. Menelaus had left for Crete[38] to bury his uncle, Crateus.[39] Hera, still jealous over the judgement of Paris, sent a storm.[38] The storm caused the lovers to land in Egypt, where the gods replaced Helen with a likeness of her made of clouds, Nephele.[40] The myth of Helen being switched is attributed to the 6th century BC Sicilian poet Stesichorus. For Homer the true Helen was in Troy. The ship then landed in Sidon before reaching Troy. Paris, fearful of getting caught, spent some time there and then sailed to Troy.[41]

Paris' abduction of Helen had several precedents. Io was taken from Mycenae, Europa was taken from Phoenicia, Jason took Medea from Colchis,[42] and the Trojan princess Hesione had been taken by Heracles, who gave her to Telamon of Salamis.[43] According to Herodotus, Paris was emboldened by these examples to steal himself a wife from Greece, and expected no retribution, since there had been none in the other cases.[44]

The gathering of Achaean forces and the first expedition

According to Homer, Menelaus and his ally, Odysseus, traveled to Troy, where they unsuccessfully sought to recover Helen by diplomatic means.[45]

Menelaus then asked Agamemnon to uphold his oath, which, as one of Helen's suitors, was to defend her marriage regardless of which suitor had been chosen. Agamemnon agreed and sent emissaries to all the Achaean kings and princes to call them to observe their oaths and retrieve Helen.[46]

Odysseus and Achilles

Since Menelaus's wedding, Odysseus had married Penelope and fathered a son, Telemachus. In order to avoid the war, he feigned madness and sowed his fields with salt. Palamedes outwitted him by placing his infant son in front of the plough's path, and Odysseus turned aside, unwilling to kill his son, so revealing his sanity and forcing him to join the war.[38][47]

According to Homer, however, Odysseus supported the military adventure from the beginning, and traveled the region with Pylos' king, Nestor, to recruit forces.[48]

At Skyros, Achilles had an affair with the king's daughter Deidamia, resulting in a child, Neoptolemus.[49] Odysseus, Telamonian Ajax, and Achilles' tutor Phoenix went to retrieve Achilles. Achilles' mother disguised him as a woman so that he would not have to go to war, but, according to one story, they blew a horn, and Achilles revealed himself by seizing a spear to fight intruders, rather than fleeing.[25] According to another story, they disguised themselves as merchants bearing trinkets and weaponry, and Achilles was marked out from the other women for admiring weaponry instead of clothes and jewelry.[50]

Pausanias said that, according to Homer, Achilles did not hide in Skyros, but rather conquered the island, as part of the Trojan War.[51]

First gathering at Aulis

The Achaean forces first gathered at Aulis. All the suitors sent their forces except King Cinyras of Cyprus. Though he sent breastplates to Agamemnon and promised to send 50 ships, he sent only one real ship, led by the son of Mygdalion, and 49 ships made of clay.[52] Idomeneus was willing to lead the Cretan contingent in Mycenae's war against Troy, but only as a co-commander, which he was granted.[53] The last commander to arrive was Achilles, who was then 15 years old.

Following a sacrifice to Apollo, a snake slithered from the altar to a sparrow's nest in a plane tree nearby. It ate the mother and her nine babies, then was turned to stone. Calchas interpreted this as a sign that Troy would fall in the tenth year of the war.[54]

Telephus

When the Achaeans left for the war, they did not know the way, and accidentally landed in Mysia, ruled by King Telephus, son of Heracles, who had led a contingent of Arcadians to settle there.[55] In the battle, Achilles wounded Telephus,[56] who had killed Thersander.[57] Because the wound would not heal, Telephus asked an oracle, "What will happen to the wound?". The oracle responded, "he that wounded shall heal". The Achaean fleet then set sail and was scattered by a storm. Achilles landed in Scyros and married Deidamia. A new gathering was set again in Aulis.[38]

Telephus went to Aulis, and either pretended to be a beggar, asking Agamemnon to help heal his wound,[58] or kidnapped Orestes and held him for ransom, demanding the wound be healed.[59] Achilles refused, claiming to have no medical knowledge. Odysseus reasoned that the spear that had inflicted the wound must be able to heal it. Pieces of the spear were scraped off onto the wound, and Telephus was healed.[60] Telephus then showed the Achaeans the route to Troy.[58]

Some scholars have regarded the expedition against Telephus and its resolution as a derivative reworking of elements from the main story of the Trojan War, but it has also been seen as fitting the story-pattern of the "preliminary adventure" that anticipates events and themes from the main narrative, and therefore as likely to be "early and integral".[61]

The second gathering

Eight years after the storm had scattered them,[62] the fleet of more than a thousand ships was gathered again. But when they had all reached Aulis, the winds ceased. The prophet Calchas stated that the goddess Artemis was punishing Agamemnon for killing either a sacred deer or a deer in a sacred grove, and boasting that he was a better hunter than she.[38] The only way to appease Artemis, he said, was to sacrifice Iphigenia, who was either the daughter of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra,[63] or of Helen and Theseus entrusted to Clytemnestra when Helen married Menelaus.[64] Agamemnon refused, and the other commanders threatened to make Palamedes commander of the expedition.[65] According to some versions, Agamemnon relented, but others claim that he sacrificed a deer in her place, or that at the last moment, Artemis took pity on the girl, and took her to be a maiden in one of her temples, substituting a lamb.[38] Hesiod says that Iphigenia became the goddess Hecate.[66]

The Achaean forces are described in detail in the Catalogue of Ships, in the second book of the Iliad. They consisted of 28 contingents from mainland Greece, the Peloponnese, the Dodecanese islands, Crete, and Ithaca, comprising 1186 pentekonters, ships with 50 rowers. Thucydides says[67] that according to tradition there were about 1200 ships, and that the Boeotian ships had 120 men, while Philoctetes' ships only had the fifty rowers, these probably being maximum and minimum. These numbers would mean a total force of 70,000 to 130,000 men. Another catalogue of ships is given by the Bibliotheca that differs somewhat but agrees in numbers. Some scholars have claimed that Homer's catalogue is an original Bronze Age document, possibly the Achaean commander's order of operations.[68][69][70] Others believe it was a fabrication of Homer.

The second book of the Iliad also lists the Trojan allies, consisting of the Trojans themselves, led by Hector, and various allies listed as Dardanians led by Aeneas, Zeleians, Adrasteians, Percotians, Pelasgians, Thracians, Ciconian spearmen, Paionian archers, Halizones, Mysians, Phrygians, Maeonians, Miletians, Lycians led by Sarpedon and Carians. Nothing is said of the Trojan language; the Carians are specifically said to be barbarian-speaking, and the allied contingents are said to have spoken multiple languages, requiring orders to be translated by their individual commanders.[71] It should be noted, however, that the Trojans and Achaeans in the Iliad share the same religion, same culture and the enemy heroes speak to each other in the same language, though this could be dramatic effect.

Nine years of war

Philoctetes

Philoctetes was Heracles' friend, and because he lit Heracles's funeral pyre when no one else would, he received Heracles' bow and arrows.[72] He sailed with seven ships full of men to the Trojan War, where he was planning on fighting for the Achaeans. They stopped either at Chryse Island for supplies,[73] or in Tenedos, along with the rest of the fleet.[74] Philoctetes was then bitten by a snake. The wound festered and had a foul smell; on Odysseus's advice, the Atreidae ordered Philoctetes to stay on Lemnos.[38] Medon took control of Philoctetes's men. While landing on Tenedos, Achilles killed king Tenes, son of Apollo, despite a warning by his mother that if he did so he would be killed himself by Apollo.[75] From Tenedos, Agamemnon sent an embassy to Priam, composed of Menelaus, Odysseus, and Palamedes, asking for Helen's return. The embassy was refused.[76]

Philoctetes stayed on Lemnos for ten years, which was a deserted island according to Sophocles' tragedy Philoctetes, but according to earlier tradition was populated by Minyans.[77]

Arrival

Calchas had prophesied that the first Achaean to walk on land after stepping off a ship would be the first to die.[78] Thus even the leading Greeks hesitated to land. Finally, Protesilaus, leader of the Phylaceans, landed first.[79] Odysseus had tricked him, in throwing his own shield down to land on, so that while he was first to leap off his ship, he was not the first to land on Trojan soil. Hector killed Protesilaus in single combat, though the Trojans conceded the beach. In the second wave of attacks, Achilles killed Cycnus, son of Poseidon. The Trojans then fled to the safety of the walls of their city.[80] Protesilaus had killed many Trojans but was killed by Hector in most versions of the story,[81] though others list Aeneas, Achates, or Ephorbus as his slayer.[82] The Achaeans buried him as a god on the Thracian peninsula, across the Troad.[83] After Protesilaus' death, his brother, Podarces, took command of his troops.

Achilles' campaigns

The Achaeans besieged Troy for nine years. This part of the war is the least developed among surviving sources, which prefer to talk about events in the last year of the war. After the initial landing the army was gathered in its entirety again only in the tenth year. Thucydides deduces that this was due to lack of money. They raided the Trojan allies and spent time farming the Thracian peninsula.[84] Troy was never completely besieged, thus it maintained communications with the interior of Asia Minor. Reinforcements continued to come until the very end. The Achaeans controlled only the entrance to the Dardanelles, and Troy and her allies controlled the shortest point at Abydos and Sestus and communicated with allies in Europe.[85]

Achilles and Ajax were the most active of the Achaeans, leading separate armies to raid lands of Trojan allies. According to Homer, Achilles conquered 11 cities and 12 islands.[86] According to Apollodorus, he raided the land of Aeneas in the Troad region and stole his cattle.[87] He also captured Lyrnassus, Pedasus, and many of the neighbouring cities, and killed Troilus, son of Priam, who was still a youth; it was said that if he reached 20 years of age, Troy would not fall. According to Apollodorus,

- He also took Lesbos and Phocaea, then Colophon, and Smyrna, and Clazomenae, and Cyme; and afterwards Aegialus and Tenos, the so-called Hundred Cities; then, in order, Adramytium and Side; then Endium, and Linaeum, and Colone. He took also Hypoplacian Thebes and Lyrnessus, and further Antandrus, and many other cities.[88]

Kakrides comments that the list is wrong in that it extends too far into the south.[89] Other sources talk of Achilles taking Pedasus, Monenia,[90] Mythemna (in Lesbos), and Peisidice.[91]

Among the loot from these cities was Briseis, from Lyrnessus, who was awarded to him, and Chryseis, from Hypoplacian Thebes, who was awarded to Agamemnon.[38] Achilles captured Lycaon, son of Priam,[92] while he was cutting branches in his father's orchards. Patroclus sold him as a slave in Lemnos,[38] where he was bought by Eetion of Imbros and brought back to Troy. Only 12 days later Achilles slew him, after the death of Patroclus.[93]

Ajax and a game of petteia

Ajax son of Telamon laid waste the Thracian peninsula of which Polymestor, a son-in-law of Priam, was king. Polymestor surrendered Polydorus, one of Priam's children, of whom he had custody. He then attacked the town of the Phrygian king Teleutas, killed him in single combat and carried off his daughter Tecmessa.[94] Ajax also hunted the Trojan flocks, both on Mount Ida and in the countryside.

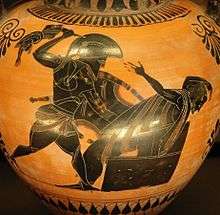

Numerous paintings on pottery have suggested a tale not mentioned in the literary traditions. At some point in the war Achilles and Ajax were playing a board game (petteia).[95][96] They were absorbed in the game and oblivious to the surrounding battle.[97] The Trojans attacked and reached the heroes, who were only saved by an intervention of Athena.[98]

The death of Palamedes

Odysseus was sent to Thrace to return with grain, but came back empty-handed. When scorned by Palamedes, Odysseus challenged him to do better. Palamedes set out and returned with a shipload of grain.[99]

Odysseus had never forgiven Palamedes for threatening the life of his son. In revenge, Odysseus conceived a plot[100] where an incriminating letter was forged, from Priam to Palamedes,[101] and gold was planted in Palamedes' quarters. The letter and gold were "discovered", and Agamemnon had Palamedes stoned to death for treason.

However, Pausanias, quoting the Cypria, says that Odysseus and Diomedes drowned Palamedes, while he was fishing, and Dictys says that Odysseus and Diomedes lured Palamedes into a well, which they said contained gold, then stoned him to death.[102]

Palamedes' father Nauplius sailed to the Troad and asked for justice, but was refused. In revenge, Nauplius traveled among the Achaean kingdoms and told the wives of the kings that they were bringing Trojan concubines to dethrone them. Many of the Greek wives were persuaded to betray their husbands, most significantly Agamemnon's wife, Clytemnestra, who was seduced by Aegisthus, son of Thyestes.[103]

Mutiny

Near the end of the ninth year since the landing, the Achaean army, tired from the fighting and from the lack of supplies, mutinied against their leaders and demanded to return to their homes. According to the Cypria, Achilles forced the army to stay.[38] According to Apollodorus, Agamemnon brought the Wine Growers, daughters of Anius, son of Apollo, who had the gift of producing by touch wine, wheat, and oil from the earth, in order to relieve the supply problem of the army.[104]

The Iliad

Chryses, a priest of Apollo and father of Chryseis, came to Agamemnon to ask for the return of his daughter. Agamemnon refused, and insulted Chryses, who prayed to Apollo to avenge his ill-treatment. Enraged, Apollo afflicted the Achaean army with plague. Agamemnon was forced to return Chryseis to end the plague, and took Achilles' concubine Briseis as his own. Enraged at the dishonour Agamemnon had inflicted upon him, Achilles decided he would no longer fight. He asked his mother, Thetis, to intercede with Zeus, who agreed to give the Trojans success in the absence of Achilles, the best warrior of the Achaeans.

After the withdrawal of Achilles, the Achaeans were initially successful. Both armies gathered in full for the first time since the landing. Menelaus and Paris fought a duel, which ended when Aphrodite snatched the beaten Paris from the field. With the truce broken, the armies began fighting again. Diomedes won great renown amongst the Achaeans, killing the Trojan hero Pandaros and nearly killing Aeneas, who was only saved by his mother, Aphrodite. With the assistance of Athena, Diomedes then wounded the gods Aphrodite and Ares. During the next days, however, the Trojans drove the Achaeans back to their camp and were stopped at the Achaean wall by Poseidon. The next day, though, with Zeus' help, the Trojans broke into the Achaean camp and were on the verge of setting fire to the Achaean ships. An earlier appeal to Achilles to return was rejected, but after Hector burned Protesilaus' ship, he allowed his close friend[105] and relative Patroclus to go into battle wearing Achilles' armour and lead his army. Patroclus drove the Trojans all the way back to the walls of Troy, and was only prevented from storming the city by the intervention of Apollo. Patroclus was then killed by Hector, who took Achilles' armour from the body of Patroclus.

Achilles, maddened with grief, swore to kill Hector in revenge. He was reconciled with Agamemnon and received Briseis back, untouched by Agamemnon. He received a new set of arms, forged by the god Hephaestus, and returned to the battlefield. He slaughtered many Trojans, and nearly killed Aeneas, who was saved by Poseidon. Achilles fought with the river god Scamander, and a battle of the gods followed. The Trojan army returned to the city, except for Hector, who remained outside the walls because he was tricked by Athena. Achilles killed Hector, and afterwards he dragged Hector's body from his chariot and refused to return the body to the Trojans for burial. The Achaeans then conducted funeral games for Patroclus. Afterwards, Priam came to Achilles' tent, guided by Hermes, and asked Achilles to return Hector's body. The armies made a temporary truce to allow the burial of the dead. The Iliad ends with the funeral of Hector.

After the Iliad

Penthesilea and the death of Achilles

Shortly after the burial of Hector, Penthesilea, queen of the Amazons, arrived with her warriors.[106] Penthesilea, daughter of Otrere and Ares, had accidentally killed her sister Hippolyte. She was purified from this action by Priam,[107] and in exchange she fought for him and killed many, including Machaon[108] (according to Pausanias, Machaon was killed by Eurypylus),[109] and according to another version, Achilles himself, who was resurrected at the request of Thetis.[110] Penthesilia was then killed by Achilles[111] who fell in love with her beauty after her death. Thersites, a simple soldier and the ugliest Achaean, taunted Achilles over his love[108] and gouged out Penthesilea's eyes.[112] Achilles slew Thersites, and after a dispute sailed to Lesbos, where he was purified for his murder by Odysseus after sacrificing to Apollo, Artemis, and Leto.[111]

While they were away, Memnon of Ethiopia, son of Tithonus and Eos,[113] came with his host to help his stepbrother Priam.[114] He did not come directly from Ethiopia, but either from Susa in Persia, conquering all the peoples in between,[115] or from the Caucasus, leading an army of Ethiopians and Indians.[116] Like Achilles, he wore armour made by Hephaestus.[117] In the ensuing battle, Memnon killed Antilochus, who took one of Memnon's blows to save his father Nestor.[118] Achilles and Memnon then fought. Zeus weighed the fate of the two heroes; the weight containing that of Memnon sank,[119] and he was slain by Achilles.[111][120] Achilles chased the Trojans to their city, which he entered. The gods, seeing that he had killed too many of their children, decided that it was his time to die. He was killed after Paris shot a poisoned arrow that was guided by Apollo.[111][113][121] In another version he was killed by a knife to the back (or heel) by Paris, while marrying Polyxena, daughter of Priam, in the temple of Thymbraean Apollo,[122] the site where he had earlier killed Troilus. Both versions conspicuously deny the killer any sort of valour, saying Achilles remained undefeated on the battlefield. His bones were mingled with those of Patroclus, and funeral games were held.[123] Like Ajax, he is represented as living after his death in the island of Leuke, at the mouth of the Danube River,[124] where he is married to Helen.[125]

The Judgment of Arms

A great battle raged around the dead Achilles. Ajax held back the Trojans, while Odysseus carried the body away.[126] When Achilles' armour was offered to the smartest warrior, the two that had saved his body came forward as competitors. Agamemnon, unwilling to undertake the invidious duty of deciding between the two competitors, referred the dispute to the decision of the Trojan prisoners, inquiring of them which of the two heroes had done most harm to the Trojans.[127] Alternatively, the Trojans and Pallas Athena were the judges[128][129] in that, following Nestor's advice, spies were sent to the walls to overhear what was said. A girl said that Ajax was braver:

- For Aias took up and carried out of the strife the hero, Peleus'

- son: this great Odysseus cared not to do.

- To this another replied by Athena's contrivance:

- Why, what is this you say? A thing against reason and untrue!

- Even a woman could carry a load once a man had put it on her

- shoulder; but she could not fight. For she would fail with fear

- if she should fight. (Scholiast on Aristophanes, Knights 1056 and Aristophanes ib)

According to Pindar, the decision was made by secret ballot among the Achaeans.[130] In all story versions, the arms were awarded to Odysseus. Driven mad with grief, Ajax desired to kill his comrades, but Athena caused him to mistake the cattle and their herdsmen for the Achaean warriors.[131] In his frenzy he scourged two rams, believing them to be Agamemnon and Menelaus.[132] In the morning, he came to his senses and killed himself by jumping on the sword that had been given to him by Hector, so that it pierced his armpit, his only vulnerable part.[133] According to an older tradition, he was killed by the Trojans who, seeing he was invulnerable, attacked him with clay until he was covered by it and could no longer move, thus dying of starvation.

The prophecies

After the tenth year, it was prophesied[134] that Troy could not fall without Heracles' bow, which was with Philoctetes in Lemnos. Odysseus and Diomedes[135] retrieved Philoctetes, whose wound had healed.[136] Philoctetes then shot and killed Paris.

According to Apollodorus, Paris' brothers Helenus and Deiphobus vied over the hand of Helen. Deiphobus prevailed, and Helenus abandoned Troy for Mt. Ida. Calchas said that Helenus knew the prophecies concerning the fall of Troy, so Odysseus waylaid Helenus.[129][137] Under coercion, Helenus told the Achaeans that they would win if they retrieved Pelops' bones, persuaded Achilles' son Neoptolemus to fight for them, and stole the Trojan Palladium.[138]

The Greeks retrieved Pelop's bones,[139] and sent Odysseus to retrieve Neoptolemus, who was hiding from the war in King Lycomedes's court in Scyros. Odysseus gave him his father's arms.[129][140] Eurypylus, son of Telephus, leading, according to Homer, a large force of Kêteioi,[141] or Hittites or Mysians according to Apollodorus,[142] arrived to aid the Trojans. He killed Machaon[109] and Peneleos,[143] but was slain by Neoptolemus.

Disguised as a beggar, Odysseus went to spy inside Troy, but was recognized by Helen. Homesick,[144] Helen plotted with Odysseus. Later, with Helen's help, Odysseus and Diomedes stole the Palladium.[129][145]

Trojan Horse

The end of the war came with one final plan. Odysseus devised a new ruse—a giant hollow wooden horse, an animal that was sacred to the Trojans. It was built by Epeius and guided by Athena,[146] from the wood of a cornel tree grove sacred to Apollo,[147] with the inscription:

- The Greeks dedicate this thank-offering to Athena for their return home.[148]

The hollow horse was filled with soldiers[149] led by Odysseus. The rest of the army burned the camp and sailed for Tenedos.[150]

When the Trojans discovered that the Greeks were gone, believing the war was over, they "joyfully dragged the horse inside the city",[151] while they debated what to do with it. Some thought they ought to hurl it down from the rocks, others thought they should burn it, while others said they ought to dedicate it to Athena.[152][153]

Both Cassandra and Laocoön warned against keeping the horse.[154] While Cassandra had been given the gift of prophecy by Apollo, she was also cursed by Apollo never to be believed. Serpents then came out of the sea and devoured either Laocoön and one of his two sons,[152] Laocoön and both his sons,[155] or only his sons,[156] a portent which so alarmed the followers of Aeneas that they withdrew to Ida.[152] The Trojans decided to keep the horse and turned to a night of mad revelry and celebration.[129] Sinon, an Achaean spy, signaled the fleet stationed at Tenedos when "it was midnight and the clear moon was rising"[157] and the soldiers from inside the horse emerged and killed the guards.[158]

The Sack of Troy

The Achaeans entered the city and killed the sleeping population. A great massacre followed which continued into the day.

- Blood ran in torrents, drenched was all the earth,

- As Trojans and their alien helpers died.

- Here were men lying quelled by bitter death

- All up and down the city in their blood.[159]

The Trojans, fuelled with desperation, fought back fiercely, despite being disorganized and leaderless. With the fighting at its height, some donned fallen enemies' attire and launched surprise counterattacks in the chaotic street fighting. Other defenders hurled down roof tiles and anything else heavy down on the rampaging attackers. The outlook was grim though, and eventually the remaining defenders were destroyed along with the whole city.

Neoptolemus killed Priam, who had taken refuge at the altar of Zeus of the Courtyard.[152][160] Menelaus killed Deiphobus, Helen's husband after Paris' death, and also intended to kill Helen, but, overcome by her beauty, threw down his sword[161] and took her to the ships.[152][162]

Ajax the Lesser raped Cassandra on Athena's altar while she was clinging to her statue. Because of Ajax's impiety, the Acheaens, urged by Odysseus, wanted to stone him to death, but he fled to Athena's altar, and was spared.[152][163]

Antenor, who had given hospitality to Menelaus and Odysseus when they asked for the return of Helen, and who had advocated so, was spared, along with his family.[164] Aeneas took his father on his back and fled, and, according to Apollodorus, was allowed to go because of his piety.[160]

The Greeks then burned the city and divided the spoils. Cassandra was awarded to Agamemnon. Neoptolemus got Andromache, wife of Hector, and Odysseus was given Hecuba, Priam's wife.[165]

The Achaeans[166] threw Hector's infant son Astyanax down from the walls of Troy,[167] either out of cruelty and hate[168] or to end the royal line, and the possibility of a son's revenge.[169] They (by usual tradition Neoptolemus) also sacrificed the Trojan princess Polyxena on the grave of Achilles as demanded by his ghost, either as part of his spoil or because she had betrayed him.[170]

Aethra, Theseus' mother, and one of Helen's handmaids,[171] was rescued by her grandsons, Demophon and Acamas.[152][172]

The returns

The gods were very angry over the destruction of their temples and other sacrilegious acts by the Achaeans, and decided that most would not return home. A storm fell on the returning fleet off Tenos island. Additionally, Nauplius, in revenge for the murder of his son Palamedes, set up false lights in Cape Caphereus (also known today as Cavo D'Oro, in Euboea) and many were shipwrecked.[173]

- Agamemnon had made it back to Argos safely with Cassandra in his possession after some stormy weather. He and Cassandra were slain by Aegisthus (in the oldest versions of the story) or by Clytemnestra or by both of them. Electra and Orestes later avenged their father, but Orestes was the one who was chased by the Furies.

- Nestor, who had the best conduct in Troy and did not take part in the looting, was the only hero who had a fast and safe return.[174] Those of his army that survived the war also reached home with him safely, but later left and colonised Metapontium in Southern Italy.[175]

- Ajax the Lesser, who had endured more than the others the wrath of the Gods, never returned. His ship was wrecked by a storm sent by Athena, who borrowed one of Zeus' thunderbolts and tore it to pieces. The crew managed to land in a rock, but Poseidon struck it, and Ajax fell in the sea and drowned. He was buried by Thetis in Myconos[176] or Delos.[177]

- Teucer, son of Telamon and half-brother of Ajax, stood trial by his father for his half-brother's death. He was disowned by his father and wasn't allowed back on Salamis Island. He was at sea near Phreattys in Peiraeus.[178] He was acquitted of responsibility but found guilty of negligence because he did not return his dead body or his arms. He left with his army (who took their wives) and founded Salamis in Cyprus.[179] The Athenians later created a political myth that his son left his kingdom to Theseus' sons (and not to Megara).

- Neoptolemus, following the advice of Helenus, who accompanied him when he traveled over land, was always accompanied by Andromache. He met Odysseus and they buried Achilles' teacher Phoenix on the land of the Ciconians. They then conquered the land of the Molossians (Epirus) and Neoptolemus had a child by Andromache, Molossus, to whom he later gave the throne.[180] Thus the kings of Epirus claimed their lineage from Achilles, and so did Alexander the Great, whose mother was of that royal house. Alexander the Great and the kings of Macedon also claimed to be descended from Heracles. Helenus founded a city in Molossia and inhabited it, and Neoptolemus gave him his mother Deidamia as wife. After Peleus died he succeeded Phtia's throne.[181] He had a feud with Orestes (son of Agamemnon) over Menelaus' daughter Hermione, and was killed in Delphi, where he was buried.[182] In Roman myths, the kingdom of Phtia was taken over by Helenus, who married Andromache. They offered hospitality to other Trojan refugees, including Aeneas, who paid a visit there during his wanderings.

- Diomedes was first thrown by a storm on the coast of Lycia, where he was to be sacrificed to Ares by king Lycus, but Callirrhoe, the king's daughter, took pity upon him, and assisted him in escaping.[183] He then accidentally landed in Attica, in Phaleron. The Athenians, unaware that they were allies, attacked them. Many were killed, and Demophon took the Palladium.[184] He finally landed in Argos, where he found his wife Aegialeia committing adultery. In disgust, he left for Aetolia.[185] According to later traditions, he had some adventures and founded Canusium and Argyrippa in Southern Italy.[186]

- Philoctetes, due to a sedition, was driven from his city and emigrated to Italy, where he founded the cities of Petilia, Old Crimissa, and Chone, between Croton and Thurii.[187] After making war on the Leucanians he founded there a sanctuary of Apollo the Wanderer, to whom also he dedicated his bow.[188]

- According to Homer, Idomeneus reached his house safe and sound.[189] Another tradition later formed. After the war, Idomeneus's ship hit a horrible storm. Idomeneus promised Poseidon that he would sacrifice the first living thing he saw when he returned home if Poseidon would save his ship and crew. The first living thing he saw was his son, whom Idomeneus duly sacrificed. The gods were angry at his murder of his own son and they sent a plague to Crete. His people sent him into exile to Calabria in Italy,[190] and then to Colophon, in Asia Minor, where he died.[191] Among the lesser Achaeans very few reached their homes.

House of Atreus

According to the Odyssey, Menelaus's fleet was blown by storms to Crete and Egypt, where they were unable to sail away due to calm winds.[192] Only five of his ships survived.[174] Menelaus had to catch Proteus, a shape-shifting sea god, to find out what sacrifices to which gods he would have to make to guarantee safe passage.[193] According to some stories the Helen who was taken by Paris was a fake, and the real Helen was in Egypt, where she was reunited with Menelaus. Proteus also told Menelaus that he was destined for Elysium (Heaven) after his death. Menelaus returned to Sparta with Helen eight years after he had left Troy.[194]

Agamemnon returned home with Cassandra to Argos. His wife Clytemnestra (Helen's sister) was having an affair with Aegisthus, son of Thyestes, Agamemnon's cousin who had conquered Argos before Agamemnon himself retook it. Possibly out of vengeance for the death of Iphigenia, Clytemnestra plotted with her lover to kill Agamemnon. Cassandra foresaw this murder, and warned Agamemnon, but he disregarded her. He was killed, either at a feast or in his bath,[195] according to different versions. Cassandra was also killed.[196] Agamemnon's son Orestes, who had been away, returned and conspired with his sister Electra to avenge their father.[197] He killed Clytemnestra and Aegisthus and succeeded to his father's throne.[198][199]

The Odyssey

Odysseus' ten-year journey home to Ithaca was told in Homer's Odyssey. Odysseus and his men were blown far off course to lands unknown to the Achaeans; there Odysseus had many adventures, including the famous encounter with the Cyclops Polyphemus, and an audience with the seer Teiresias in Hades. On the island of Thrinacia, Odysseus' men ate the cattle sacred to the sun-god Helios. For this sacrilege Odysseus' ships were destroyed, and all his men perished. Odysseus had not eaten the cattle, and was allowed to live; he washed ashore on the island of Ogygia, and lived there with the nymph Calypso. After seven years, the gods decided to send Odysseus home; on a small raft, he sailed to Scheria, the home of the Phaeacians, who gave him passage to Ithaca.

Once in his home land, Odysseus traveled disguised as an old beggar. He was recognised by his dog, Argos, who died in his lap. He then discovered that his wife, Penelope, had been faithful to him during the 20 years he was absent, despite the countless suitors that were eating his food and spending his property. With the help of his son Telemachus, Athena, and Eumaeus, the swineherd, he killed all of them except Medon, who had been polite to Penelope, and Phemius, a local singer who had only been forced to help the suitors against Penelope. Penelope tested Odysseus and made sure it was him, and he forgave her. The next day the suitors' relatives tried to take revenge on him but they were stopped by Athena.

The Telegony

The Telegony picks up where the Odyssey leaves off, beginning with the burial of the dead suitors, and continues until the death of Odysseus.[200] Some years after Odysseus' return, Telegonus, the son of Odysseus and Circe, came to Ithaca and plundered the island. Odysseus, attempting to fight off the attack, was killed by his unrecognized son. After Telegonus realized he had killed his father, he brought the body to his mother Circe, along with Telemachus and Penelope. Circe made them immortal; then Telegonus married Penelope and Telemachus married Circe.

The Aeneid

The journey of the Trojan survivor Aeneas and his resettling of Trojan refugees in Italy are the subject of the Latin epic poem The Aeneid by Virgil. Writing during the time of Augustus, Virgil has his hero give a first-person account of the fall of Troy in the second of the Aeneid 's twelve books; the Trojan Horse, which does not appear in "The Iliad", became legendary from Virgil's account.

Aeneas leads a group of survivors away from the city, among them his son Ascanius (also known as Iulus), his trumpeter Misenus, father Anchises, the healer Iapyx, his faithful sidekick Achates, and Mimas as a guide. His wife Creusa is killed during the sack of the city. Aeneas also carries the Lares and Penates of Troy, which the historical Romans claimed to preserve as guarantees of Rome's own security.

The Trojan survivors escape with a number of ships, seeking to establish a new homeland elsewhere. They land in several nearby countries that prove inhospitable, and are finally told by an oracle that they must return to the land of their forebears. They first try to establish themselves in Crete, where Dardanus had once settled, but find it ravaged by the same plague that had driven Idomeneus away. They find the colony led by Helenus and Andromache, but decline to remain. After seven years they arrive in Carthage, where Aeneas has an affair with Queen Dido. (Since according to tradition Carthage was founded in 814 BC, the arrival of Trojan refugees a few hundred years earlier exposes chronological difficulties within the mythic tradition.) Eventually the gods order Aeneas to continue onward, and he and his people arrive at the mouth of the Tiber River in Italy. Dido commits suicide, and Aeneas's betrayal of her was regarded as an element in the long enmity between Rome and Carthage that expressed itself in the Punic Wars and led to Roman hegemony.

At Cumae, the Sibyl leads Aeneas on an archetypal descent to the underworld, where the shade of his dead father serves as a guide; this book of the Aeneid directly influenced Dante, who has Virgil act as his narrator's guide. Aeneas is given a vision of the future majesty of Rome, which it was his duty to found, and returns to the world of the living. He negotiates a settlement with the local king, Latinus, and was wed to his daughter, Lavinia. This triggered a war with other local tribes, which culminated in the founding of the settlement of Alba Longa, ruled by Aeneas and Lavinia's son Silvius. Roman myth attempted to reconcile two different founding myths: three hundred years later, in the more famous tradition, Romulus and Remus founded Rome. The Trojan origins of Rome became particularly important in the propaganda of Julius Caesar, whose family claimed descent from Venus through Aeneas's son Iulus (hence the Latin gens name Iulius), and during the reign of Augustus; see for instance the Tabulae Iliacae and the "Troy Game" presented frequently by the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

Dates of the Trojan War

Since this war was considered among the ancient Greeks as either the last event of the mythical age or the first event of the historical age, several dates are given for the fall of Troy. They usually derive from genealogies of kings. Ephorus gives 1135 BC,[201] Sosibius 1172 BC,[202] Eratosthenes 1184 BC/1183 BC,[203] Timaeus 1193 BC,[204] the Parian marble 1209 BC/1208 BC,[205] Dicaearchus 1212 BC,[206] Herodotus around 1250 BC,[207] Eretes 1291 BC,[208] while Douris 1334 BC.[209] As for the exact day Ephorus gives 23/24 Thargelion (May 6 or 7), Hellanicus 12 Thargelion (May 26)[210] while others give the 23rd of Sciroforion (July 7) or the 23rd of Ponamos (October 7).

The glorious and rich city Homer describes was believed to be Troy VI by many twentieth century authors, destroyed in 1275 BC, probably by an earthquake. Its follower Troy VIIa, destroyed by fire at some point during the 1180s BC, was long considered a poorer city, but since the excavation campaign of 1988 it has risen to the most likely candidate.

Historical basis

The historicity of the Trojan War is still subject to debate. Most classical Greeks thought that the war was a historical event, but many believed that the Homeric poems had exaggerated the events to suit the demands of poetry. For instance, the historian Thucydides, who is known for being critical, considers it a true event but doubts that 1,186 ships were sent to Troy. Euripides started changing Greek myths at will, including those of the Trojan War. Near year 100, Dio Chrysostom argued that while the war was historical, it ended with the Trojans winning, and the Greeks attempted to hide that fact.[211] Around 1870 it was generally agreed in Western Europe that the Trojan War had never happened and Troy never existed.[212] Then Heinrich Schliemann popularized his excavations at Hisarlik, which he and others believed to be Troy, and of the Mycenaean cities of Greece. Today many scholars agree that the Trojan War is based on a historical core of a Greek expedition against the city of Troy, but few would argue that the Homeric poems faithfully represent the actual events of the war.

In November 2001, geologist John C. Kraft and classicist John V. Luce presented the results of investigations into the geology of the region that had started in 1977.[213][214][215] The geologists compared the present geology with the landscapes and coastal features described in the Iliad and other classical sources, notably Strabo's Geographia. Their conclusion was that there is regularly a consistency between the location of Troy as identified by Schliemann (and other locations such as the Greek camp), the geological evidence, and descriptions of the topography and accounts of the battle in the Iliad.

In the twentieth century scholars have attempted to draw conclusions based on Hittite and Egyptian texts that date to the time of the Trojan War. While they give a general description of the political situation in the region at the time, their information on whether this particular conflict took place is limited. Andrew Dalby notes that while the Trojan War most likely did take place in some form and is therefore grounded in history, its true nature is and will be unknown.[216] Hittite archives, like the Tawagalawa letter mention of a kingdom of Ahhiyawa (Achaea, or Greece) that lies beyond the sea (that would be the Aegean) and controls Milliwanda, which is identified with Miletus. Also mentioned in this and other letters is the Assuwa confederation made of 22 cities and countries which included the city of Wilusa (Ilios or Ilium). The Milawata letter implies this city lies on the north of the Assuwa confederation, beyond the Seha river. While the identification of Wilusa with Ilium (that is, Troy) is always controversial, in the 1990s it gained majority acceptance. In the Alaksandu treaty (ca. 1280 BC) the king of the city is named Alaksandu, and Paris's name in the Iliad (among other works) is Alexander. The Tawagalawa letter (dated ca. 1250 BC) which is addressed to the king of Ahhiyawa actually says:

- Now as we have come to an agreement on Wilusa over which we went to war...

Formerly under the Hittites, the Assuwa confederation defected after the battle of Kadesh between Egypt and the Hittites (ca. 1274 BC). In 1230 BC Hittite king Tudhaliya IV (ca. 1240–1210 BC) campaigned against this federation. Under Arnuwanda III (ca. 1210–1205 BC) the Hittites were forced to abandon the lands they controlled in the coast of the Aegean. It is possible that the Trojan War was a conflict between the king of Ahhiyawa and the Assuwa confederation. This view has been supported in that the entire war includes the landing in Mysia (and Telephus' wounding), Achilles's campaigns in the North Aegean and Telamonian Ajax's campaigns in Thrace and Phrygia. Most of these regions were part of Assuwa.[69][217] It has also been noted that there is great similarity between the names of the Sea Peoples, which at that time were raiding Egypt, as they are listed by Ramesses III and Merneptah, and of the allies of the Trojans.[218]

That most Achaean heroes did not return to their homes and founded colonies elsewhere was interpreted by Thucydides as being due to their long absence.[219] Nowadays the interpretation followed by most scholars is that the Achaean leaders driven out of their lands by the turmoil at the end of the Mycenaean era preferred to claim descent from exiles of the Trojan War.[220]

In popular culture

The inspiration provided by these events produced many literary works, far more than can be listed here. The siege of Troy provided inspiration for many works of art, most famously Homer's Iliad, set in the last year of the siege. Some of the others include Troades by Euripides, Troilus and Criseyde by Geoffrey Chaucer, Troilus and Cressida by William Shakespeare, Iphigenia and Polyxena by Samuel Coster, Palamedes by Joost van den Vondel and Les Troyens by Hector Berlioz.

Films based on the Trojan War include Troy (2004). The war has also been featured in many books, television series, and other creative works.

References

- ↑ Bryce, Trevor (2005). The Trojans and their neighbours. Taylor & Francis. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-415-34959-8.

- ↑ Rutter, Jeremy B. "Troy VII and the Historicity of the Trojan War". Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- ↑ In the second edition of his In Search of the Trojan War, Michael Wood notes developments that were made in the intervening ten years since his first edition was published. Scholarly skepticism about Schliemann's identification has been dispelled by the more recent archaeological discoveries, linguistic research, and translations of clay-tablet records of contemporaneous diplomacy. Wood, Michael (1998). "Preface". In Search of the Trojan War (2 ed.). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 4. ISBN 0-520-21599-0.

Now, more than ever, in the 125 years since Schliemann put his spade into Hisarlik, there appears to be a historical basis to the tale of Troy

- ↑ Wood (1985: 116–118)

- ↑ Wood (1985: 19)

- ↑ It is unknown whether this Proclus is the Neoplatonic philosopher, in which case the summary dates to the 5th century AD, or whether he is the lesser-known grammarian of the 2nd century AD. See Burgess, p. 12.

- ↑ Burgess, pp. 10–12; cf. W. Kullmann (1960), Die Quellen der Ilias.

- ↑ Burgess, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Scholium on Homer A.5.

- ↑ Plato, Republic 2,379e.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 3.1, Hesiod Fragment 204,95ff.

- ↑ Apollonius Rhodius 4.757.

- ↑ Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound 767.

- ↑ Scholiast on Homer’s Iliad; Hyginus, Fabulae 54; Ovid, Metamorphoses 11.217.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Library 3.168.

- ↑ Pindar, Nemean 5 ep2; Pindar, Isthmian 8 str3–str5.

- ↑ Hesiod, Catalogue of Women fr. 57; Cypria fr. 4.

- ↑ Photius, Myrobiblion 190.

- ↑ P.Oxy. 56, 3829 (L. Koppel, 1989)

- ↑ Hyginus, Fabulae 92.

- ↑ Apollodorus Epitome E.3.2

- ↑ Pausanias, 15.9.5.

- ↑ Euripides Andromache 298; Div. i. 21; Apollodorus, Library 3.12.5.

- ↑ Homer Iliad I.410

- 1 2 Apollodorus, Library 3.13.8.

- ↑ Apollonius Rhodius 4.869–879; Apollodorus, Library 3.13.6.

- ↑ Frazer on Apollodorus, Library 3.13.6.

- ↑ Alluded to in Statius, Achilleid 1.269–270.

- ↑ Hyginus, Fabulae 96.

- ↑ Apollodorus 3.10.7.

- ↑ Pausanias 1.33.1; Apollodorus, Library 3.10.7.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Library 3.10.5; Hyginus, Fabulae 77.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Library 3.10.9.

- ↑ Pausanias 3.20.9.

- ↑ Ptolemy Hephaestion, New History 4 (as summarized in Photius, Myriobiblon 190).

- ↑ Pindar, Pythian 11 ep4; Apollodorus, Library 3.11.15.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 2.15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Proclus Chrestomathy 1

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 3.3.

- ↑ Euripides, Helen 40.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 3.4.

- ↑ Herodotus, Histories 1.2.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Library 3.12.7.

- ↑ Herodotus, 1.3.1.

- ↑ Il. 3.205-6; 11.139

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 3.6.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 3.7.

- ↑ Il.11.767-70, (lines rejected by Aristophanes and Aristarchus)

- ↑ Statius, Achilleid 1.25

- ↑ Scholiast on Homer's Iliad 19.326; Ovid, Metamorphoses 13.162 ff.

- ↑ Pausanias, 1.22.6.

- ↑ Homer, Iliad 11.19 ff.; Apollodurus, Epitome 3.9.

- ↑ Philostratus, Heroicus 7.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 3.15.

- ↑ Pausanias, 1.4.6.

- ↑ Pindar, Isthmian 8.

- ↑ Pausanias, 9.5.14.

- 1 2 Apollodorus, Epitome 3.20.

- ↑ Aeschylus fragment 405–410

- ↑ Pliny, Natural History 24.42, 34.152.

- ↑ Davies, esp. pp. 8, 10.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 3.19.

- ↑ Philodemus, On Piety.

- ↑ Antoninus Liberalis, Metamorphoses 27.

- ↑ Ptolemy Hephaestion, New History 5 (as summarized in Photius, Myriobiblon 190).

- ↑ Pausanias, 1.43.1.

- ↑ History of the Pelloponesian War 1,10.

- ↑ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους (History of the Greek Nation) vol. A, Ekdotiki Athinon, Athens 1968.

- 1 2 Pantelis Karykas, Μυκηναίοι Πολεμιστές (Mycenian Warriors), Athens 1999.

- ↑ Vice Admiral P.E. Konstas R.H.N.,Η ναυτική ηγεμονία των Μυκηνών (The naval hegemony of Mycenae), Athens 1966

- ↑ Homer, Iliad Β.803–806.

- ↑ Diodorus iv,38.

- ↑ Pausanias 8.33.4

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 3.27.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 3.26.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 3.28.

- ↑ Herodotus 4.145.3.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 3.29.

- ↑ Pausianias 4.2.7.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 3.31.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 3.30.

- ↑ Eustathius on Homer, Iliad ii.701.

- ↑ Scholiast on Lycophron 532.

- ↑ Thucydides 1.11.

- ↑ Papademetriou Konstantinos, "Τα όπλα του Τρωϊκού Πολέμου" ("The weapons of the Trojan War"), Panzer Magazine issue 14, June–July 2004, Athens.

- ↑ Iliad I.328

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 3.32.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 3.33; translation, Sir James George Frazer.

- ↑ Volume 5 p.80

- ↑ Demetrius (2nd century BC) Scholium on Iliad Z,35

- ↑ Parthenius Ερωτικά Παθήματα 21

- ↑ Apollodorus, Library 3.12.5.

- ↑ Homer, Iliad Φ 35–155.

- ↑ Dictis Cretensis ii. 18; Sophocles, Ajax 210.

- ↑ "Petteia".

- ↑ "Greek Board Games".

- ↑ "Latrunculi".

- ↑ Kakrides vol. 5 p. 92.

- ↑ Servius, Scholium on Virgil's Aeneid 2.81

- ↑ According to other accounts Odysseus, with the other Greek captains, including Agamemnon, conspired together against Palamedes, as all were envious of his accomplishments. See Simpson, Gods & Heroes of the Greeks: The Library of Apollodorus, p. 251.

- ↑ According to Apollodorus Epitome 3.8, Odysseus forced a Phrygian prisoner, to write the letter.

- ↑ Pausanias 10.31.2; Simpson, Gods & Heroes of the Greeks: The Library of Apollodorus, p. 251.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 6.9.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 3.10

- ↑ The exact nature of Achilles' relationship to Patroclus is the subject of some debate. See Achilles and Patroclus for details.

- ↑ Scholiast on Homer, Iliad. xxiv. 804.

- ↑ Quintus of Smyrna, Posthomerica i.18 ff.

- 1 2 Apollodorus, Epitome 5.1.

- 1 2 Pausanias 3.26.9.

- ↑ Ptolemy Hephaestion, New History Bk6 (as summarized in Photius, Myriobiblon 190)

- 1 2 3 4 Proclus, Chrestomathy 2, Aethiopis.

- ↑ Tzetzes, Scholiast on Lycophron 999.

- 1 2 Apollodorus, Epitome 5.3.

- ↑ Tzetzes ad Lycophroon 18.

- ↑ Pausanias 10.31.7.

- ↑ Dictys Cretensis iv. 4.

- ↑ Virgil, Aeneid 8.372.

- ↑ Pindarus Pythian vi. 30.

- ↑ Quintus Smyrnaeus ii. 224.

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 4.75.4.

- ↑ Pausanias 1.13.9.

- ↑ Euripedes, Hecuba 40.

- ↑ Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica iv. 88–595.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 5.5.

- ↑ Pausanias 3.19.13.

- ↑ Argument of Sophocles' Ajax

- ↑ Scholiast on Homer's Odyssey λ.547.

- ↑ Homer, Odyssey λ 542.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Proclus, Chrestomathy 3, Little Iliad.

- ↑ Pindar, Nemean Odes 8.46(25).

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 5.6.

- ↑ Zenobius, Cent. i.43.

- ↑ Sophocles, Ajax 42, 277, 852.

- ↑ Either by Calchas, (Apollodorus, Epitome 5.8; Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica 9.325–479), or by Paris' brother Helenus (Proclus, Chrestomathy 3, Little Iliad; Sophocles, Philoctetes 604–613; Tzetzes, Posthomerica 571–595).

- ↑ This is according to Apollodorus, Epitome 5.8, Hyginus, Fabulae 103, Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica 9.325–479, and Euripides, Philoctetes—but Sophocles, Philoctetes says Odysseus and Neoptolemus, while Proclus, Chrestomathy 3, Little Iliad says Diomedes alone.

- ↑ Philoctetes was cured by a son of Asclepius, either Machaon, (Proclus, Chrestomathy 3, Little Iliad; Tzetzes, Posthomerica 571–595) or his brother Podalirius (Apollodorus, Epitome 5.8; Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica 9.325–479).

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 5.9.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 5.10; Pausanias 5.13.4.

- ↑ Pausanias 5.13.4–6, says that Pelop's shoulder-blade was brought to Troy from Pisa, and on its return home was lost at sea, later to be found by a fisherman, and identified as Pelop's by the Oracle at Delphi.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 5.11.

- ↑ Odyssey λ.520

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 5.12.

- ↑ Pausanias 9.5.15.

- ↑ Homer, Odyssey 4.242 ff.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 5.13.

- ↑ Homer, Odyssey 8.492–495; Apollodorus, Epitome 5.14.

- ↑ Pausanias, 3.13.5.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 5.15, Simpson, p 246.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 5.14, says the hollow horse held 50, but attributes to the author of the Little Iliad a figure of 3,000, a number that Simpson, p 265, calls "absurd", saying that the surviving fragments only say that the Greeks put their "best men" inside the horse. Tzetzes, Posthomerica 641–650, gives a figure of 23, while Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica xii.314–335, gives the names of thirty, and says that there were more. In late tradition it seems it was standardized at 40.

- ↑ Homer, Odyssey 8.500–504; Apollodorus, Epitome 5.15.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 5.16, as translated by Simpson, p. 246. Proculus, Chrestomathy 3, Little Iliad, says that the Trojans pulled down a part of their walls to admit the horse.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Proclus, Chrestomathy 4, Iliou Persis.

- ↑ Homer, Odyssey 8.505 ff.; Apollodorus, Epitome 5.16–15.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 5.17 says that Cassandra warned of an armed force inside the horse, and that Laocoön agreed.

- ↑ Virgil, Aeneid 2.199–227; Hyginus, Fabulae 135;

- ↑ Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica xii.444–497; Apollodorus, Epitome 5.18.

- ↑ Scholiast on Lycophroon, 344.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 5.19–20.

- ↑ Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica xiii.100–104,Translation by A.S. Way, 1913.

- 1 2 Apollodorus. Epitome 5.21.

- ↑ Aristophanes, Lysistrata 155; Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica xiii.423–457.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 5.22.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 5.22; Pausanias 10.31.2; Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica xiii.462–473; Virgil, Aeneid 403–406. The rape of Cassandra was a popular theme of ancient Greek paintings, see Pausanias, 1.15.2, 5.11.6, 5.19.5, 10.26.3.

- ↑ Homer, Iliad 3.203–207, 7.347–353; Apollodorus, Epitome, 5.21; Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica xiii.322–331, Livy, 1.1; Pausanias, 10.26.8, 27.3 ff.; Strabo, 13.1.53.

- ↑ Apollodorus. Epitome 5.23.

- ↑ Proclus, Chrestomathy 4, Ilio Persis, says Odysseus killed Astyanax, while Pausanias, 10.25.9, says Neoptolemus.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 5.23.

- ↑ Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica xiii.279–285.

- ↑ Euripides, Trojan Women 709–739, 1133–1135; Hyginus, Fabulae 109.

- ↑ Euripides, Hecuba 107–125, 218–224, 391–393, 521–582; Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica xiv.193–328.

- ↑ Homer, Iliad 3.144.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 5.22; Pausanias, 10.25.8; Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica xiii.547–595.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 6.11.

- 1 2 Apollodorus, Epitome 5.24.

- ↑ Strabo, 6.1.15.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 6.6.

- ↑ Scholiast on Homer, Iliad 13.66.

- ↑ Pausanias, 1.28.11.

- ↑ Pausanias, 8.15.7

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 6.12

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 6.13.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 6.14.

- ↑ Plutarch, 23.

- ↑ Pausanias, 1.28.9.

- ↑ Tzetzes ad Lycophroon 609.

- ↑ Strabo, 6.3.9.

- ↑ Strabo, 6.1.3.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 6.15b; Strabo, 6.1.3.

- ↑ Homer, Odyssey 3.191.

- ↑ Virgil, Aeneid 3.400

- ↑ Scholiast on Homer's Odyssey 13.259.

- ↑ Homer, Odyssey 4.360.

- ↑ Homer, Odyssey 4.382.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 6.29.

- ↑ Pausanias, 2.16.6.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Epitome 6.23.

- ↑ Homer, Odyssey 1.30, 298.

- ↑ Pausanias, 2.16.7.

- ↑ Sophocles, Electra 1405.

- ↑ Proclus Chrestomathy 2, Telegony

- ↑ FGrHist 70 F 223

- ↑ FGrHist 595 F 1

- ↑ Chronographiai FGrHist 241 F 1d

- ↑ FGrHist 566 F 125

- ↑ FGrHist 239, §24

- ↑ Bios Hellados

- ↑ Histories 2,145

- ↑ FGrHist 242 F 1

- ↑ FGrHist 76 F 41

- ↑ FGrHist 4 F 152

- ↑ Dio Chrysostom The Eleventh Discourse Maintaining that Troy was not Captured

- ↑ Yale University: Introduction to Ancient Greek History: Lecture 2

- ↑ Kraft, J. C.; Rapp, G. (Rip); Kayan, I.; Luce, J. V. (2003). "Harbor areas at ancient Troy: Sedimentology and geomorphology complement Homer's Iliad". Geology 31 (2): 163. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2003)031<0163:HAAATS>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Geologists show Homer got it right at the Wayback Machine (archived April 2, 2003)

- ↑ Iliad, Discovery.

- ↑ Wilson, Emily. Was The Iliad written by a woman?, Slate Magazine, December 12, 2006. Accessed June 30, 2008.

- ↑ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους (History of the Greek Nation) Volume A. Athens: Ekdotiki Athinon, 1968.

- ↑ Phoenix Data Systems - Attacks on Egypt

- ↑ Thucydides. The Peloponnesian War, 1.12.2.

- ↑ Graves, Robert. The Greek Myths, "The Returns".

Further reading

Ancient authors

- Apollodorus, Gods & Heroes of the Greeks: The Library of Apollodorus, translated by Michael Simpson, The University of Massachusetts Press, (1976). ISBN 0-87023-205-3.

- Apollodorus, Apollodorus: The Library, translated by Sir James George Frazer, two volumes, Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press and London: William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Volume 1: ISBN 0-674-99135-4. Volume 2: ISBN 0-674-99136-2.

- Euripides, Andromache, in Euripides: Children of Heracles, Hippolytus, Andromache, Hecuba, with an English translation by David Kovacs. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. (1996). ISBN 0-674-99533-3.

- Euripides, Helen, in The Complete Greek Drama, edited by Whitney J. Oates and Eugene O'Neill, Jr. in two volumes. 1. Helen, translated by E. P. Coleridge. New York. Random House. 1938.

- Euripides, Hecuba, in The Complete Greek Drama, edited by Whitney J. Oates and Eugene O'Neill, Jr. in two volumes. 1. Hecuba, translated by E. P. Coleridge. New York. Random House. 1938.

- Herodotus, Histories, A. D. Godley (translator), Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1920; ISBN 0-674-99133-8. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library].

- Pausanias, Description of Greece, (Loeb Classical Library) translated by W. H. S. Jones; Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. (1918). Vol 1, Books I–II, ISBN 0-674-99104-4; Vol 2, Books III–V, ISBN 0-674-99207-5; Vol 3, Books VI–VIII.21, ISBN 0-674-99300-4; Vol 4, Books VIII.22–X, ISBN 0-674-99328-4.

- Proclus, Chrestomathy, in Fragments of the Kypria translated by H.G. Evelyn-White, 1914 (public domain).

- Proclus, Proclus' Summary of the Epic Cycle, trans. Gregory Nagy.

- Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica, in Quintus Smyrnaeus: The Fall of Troy, Arthur Sanders Way (Ed. & Trans.), Loeb Classics #19; Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA. (1913). (1962 edition: ISBN 0-674-99022-6).

- Strabo, Geography, translated by Horace Leonard Jones; Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, Ltd. (1924)

Modern authors

| Greek Mythology |

|---|

|

| Deities |

|

|

| Heroes and heroism |

|

| Related |

| Greek mythology portal |

- Burgess, Jonathan S. 2004. The Tradition of the Trojan War in Homer and the Epic Cycle (Johns Hopkins). ISBN 0-8018-7890-X.

- Castleden, Rodney. The Attack on Troy. Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK: Pen and Sword Books, 2006 (hardcover, ISBN 1-84415-175-1).

- Davies, Malcolm (2000). "Euripides Telephus Fr. 149 (Austin) and the Folk-Tale Origins of the Teuthranian Expedition" (PDF). Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 133: 7–10.

- Durschmied, Erik. The Hinge Factor:How Chance and Stupidity Have Changed History. Coronet Books; New Ed edition (7 Oct 1999).

- Frazer, Sir James George, Apollodorus: The Library, two volumes, Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press and London: William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Volume 1: ISBN 0-674-99135-4. Volume 2: ISBN 0-674-99136-2.

- Graves, Robert. The Greek Myths, Penguin (Non-Classics); Cmb/Rep edition (April 6, 1993). ISBN 0-14-017199-1.

- Kakridis, J., 1988. Ελληνική Μυθολογία ("Greek mythology"), Ekdotiki Athinon, Athens.

- Karykas, Pantelis, 2003. Μυκηναίοι Πολεμιστές ("Mycenean Warriors"), Communications Editions, Athens.

- Latacz, Joachim. Troy and Homer: Towards a Solution of an Old Mystery. New York: Oxford University Press (USA), 2005 (hardcover, ISBN 0-19-926308-6).

- Simpson, Michael. Gods & Heroes of the Greeks: The Library of Apollodorus, The University of Massachusetts Press, (1976). ISBN 0-87023-205-3.

- Strauss, Barry. The Trojan War: A New History. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006 (hardcover, ISBN 0-7432-6441-X).

- Thompson, Diane P. The Trojan War: Literature and Legends from the Bronze Age to the Present. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-1737-4.

- Troy: From Homer's Iliad to Hollywood Epic, edited by Martin M. Winkler. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 2007 (hardcover, ISBN 1-4051-3182-9; paperback, ISBN 1-4051-3183-7).

- Wood, Michael. In Search of the Trojan War. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998 (paperback, ISBN 0-520-21599-0); London: BBC Books, 1985 (ISBN 0-563-20161-4).

External links

-

Media related to Trojan War at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Trojan War at Wikimedia Commons - Was There a Trojan War? Maybe so. From Archeology, a publication of the Archeological Institute of America. May/June 2004

- The Trojan War at Greek Mythology Link

- The Legend of the Trojan War

- Mortal Women of the Trojan War

- The Historicity of the Trojan War The location of Troy and possible connections with the city of Teuthrania.

- The Greek Age of Bronze "Trojan war"

- The Trojan War: A Prologue to Homer's Iliad

- BBC audio podcast Melvyn Bragg interviews Edith Hall and others on historicity, history and archaeology of the war. [Play]

|