Decibel

| dB | power ratio | amplitude ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 10 000 000 000 | 100 000 | ||

| 90 | 1 000 000 000 | 31 623 | ||

| 80 | 100 000 000 | 10 000 | ||

| 70 | 10 000 000 | 3 162 | ||

| 60 | 1 000 000 | 1 000 | ||

| 50 | 100 000 | 316 | .2 | |

| 40 | 10 000 | 100 | ||

| 30 | 1 000 | 31 | .62 | |

| 20 | 100 | 10 | ||

| 10 | 10 | 3 | .162 | |

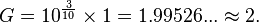

| 6 | 3 | .981 | 1 | .995 (~2) |

| 3 | 1 | .995 (~2) | 1 | .413 |

| 1 | 1 | .259 | 1 | .122 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| −1 | 0 | .794 | 0 | .891 |

| −3 | 0 | .501 (~1/2) | 0 | .708 |

| −6 | 0 | .251 | 0 | .501 (~1/2) |

| −10 | 0 | .1 | 0 | .316 2 |

| −20 | 0 | .01 | 0 | .1 |

| −30 | 0 | .001 | 0 | .031 62 |

| −40 | 0 | .000 1 | 0 | .01 |

| −50 | 0 | .000 01 | 0 | .003 162 |

| −60 | 0 | .000 001 | 0 | .001 |

| −70 | 0 | .000 000 1 | 0 | .000 316 2 |

| −80 | 0 | .000 000 01 | 0 | .000 1 |

| −90 | 0 | .000 000 001 | 0 | .000 031 62 |

| −100 | 0 | .000 000 000 1 | 0 | .000 01 |

| An example scale showing power ratios x and amplitude ratios √x and dB equivalents 10 log10 x. It is easier to grasp and compare 2- or 3-digit numbers than to compare up to 10 digits. | ||||

The decibel (dB) is a logarithmic unit used to express the ratio of two values of a physical quantity, often power or intensity. One of these values is often a standard reference value, in which case the decibel is used to express the level of the other value relative to this reference. The number of decibels is ten times the logarithm to base 10 of the ratio of two power quantities,[1] or of the ratio of the squares of two field amplitude quantities. One decibel is one tenth of one bel, named in honor of Alexander Graham Bell; however, the bel is seldom used.

The definition of the decibel is based on the measurement of power in telephony of the early 20th century in the Bell System in the United States. Today, the unit is used for a wide variety of measurements in science and engineering, most prominently in acoustics, electronics, and control theory. In electronics, the gains of amplifiers, attenuation of signals, and signal-to-noise ratios are often expressed in decibels. The decibel confers a number of advantages, such as the ability to conveniently represent very large or small numbers, and the ability to carry out multiplication of ratios by simple addition and subtraction. By contrast, use of the decibel complicates operations of addition and subtraction.

A change in power by a factor of 10 corresponds to a 10 dB change in level. At the half power point an audio circuit or an antenna exhibits an attenuation of approximately 3dB. A change in voltage by a factor of 10 results in a change in power by a factor of 100, which corresponds to a 20 dB change in level. A change in voltage ratio by a factor of 2 (equivalently factor of 4 in power change) approximately corresponds to a 6.02 dB change in level.

The decibel symbol is often qualified with a suffix that indicates the reference quantity that has been used or some other property of the quantity being measured. For example, dBm indicates a reference power of one milliwatt, while dBu is referenced to approximately 0.775 volts RMS.[2]

In the International System of Quantities, the decibel is defined as a unit of measurement for quantities of type level or level difference, which are defined as the logarithm of the ratio of power- or field-type quantities.[3]

History

The decibel originates from methods used to quantify signal loss in telegraph and telephone circuits. The unit for loss was originally Miles of Standard Cable (MSC). 1 MSC corresponded to the loss of power over a 1 mile (approximately 1.6 km) length of standard telephone cable at a frequency of 5000 radians per second (795.8 Hz), and matched closely the smallest attenuation detectable to the average listener. The standard telephone cable implied was "a cable having uniformly distributed resistance of 88 ohms per loop mile and uniformly distributed shunt capacitance of 0.054 microfarad per mile" (approximately 19 gauge).[4]

In 1924, Bell Telephone Laboratories received favorable response to a new unit definition among members of the International Advisory Committee on Long Distance Telephony in Europe and replaced the MSC with the Transmission Unit (TU). 1 TU was defined such that the number of TUs was ten times the base-10 logarithm of the ratio of measured power to a reference power level.[5] The definition was conveniently chosen such that 1 TU approximated 1 MSC; specifically, 1 MSC was 1.056 TU. In 1928, the Bell system renamed the TU into the decibel,[6] being one tenth of a newly defined unit for the base-10 logarithm of the power ratio. It was named the bel, in honor of the telecommunications pioneer Alexander Graham Bell.[7] The bel is seldom used, as the decibel was the proposed working unit.[8]

The naming and early definition of the decibel is described in the NBS Standard's Yearbook of 1931:[9]

Since the earliest days of the telephone, the need for a unit in which to measure the transmission efficiency of telephone facilities has been recognized. The introduction of cable in 1896 afforded a stable basis for a convenient unit and the "mile of standard" cable came into general use shortly thereafter. This unit was employed up to 1923 when a new unit was adopted as being more suitable for modern telephone work. The new transmission unit is widely used among the foreign telephone organizations and recently it was termed the "decibel" at the suggestion of the International Advisory Committee on Long Distance Telephony.The decibel may be defined by the statement that two amounts of power differ by 1 decibel when they are in the ratio of 100.1 and any two amounts of power differ by N decibels when they are in the ratio of 10N(0.1). The number of transmission units expressing the ratio of any two powers is therefore ten times the common logarithm of that ratio. This method of designating the gain or loss of power in telephone circuits permits direct addition or subtraction of the units expressing the efficiency of different parts of the circuit...

In April 2003, the International Committee for Weights and Measures (CIPM) considered a recommendation for the inclusion of the decibel in the International System of Units (SI), but decided against the proposal.[10] However, the decibel is recognized by other international bodies such as the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) and International Organization for Standardization (ISO).[11] The IEC permits the use of the decibel with field quantities as well as power and this recommendation is followed by many national standards bodies, such as NIST, which justifies the use of the decibel for voltage ratios.[12] The term field quantity is deprecated by ISO 80000-1, which favors root-power. In spite of their widespread use, suffixes (such as in dBA or dBV) are not recognized by the IEC or ISO.

Definition

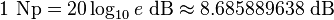

The ISO Standard 80000-3:2006 defines the following quantities. The decibel (dB) is one tenth of the bel (B): 1 B = 10 dB. The bel is (1/2) ln(10) nepers (Np): 1 B = (1/2) ln(10) Np = ln(√10) Np. The neper is the change in the level of a field quantity when the field quantity changes by a factor of e, that is 1 Np = ln(e) = 1 (thereby relating all of the units as nondimensional natural log of field-quantity ratios, 1 dB = 0.11513…Np = 0.11513.... Finally, the level of a quantity is the logarithm of the ratio of the value of that quantity to a reference value of the same quantity.

Therefore, the bel represents the logarithm of a ratio between two power quantities of 10:1, or the logarithm of a ratio between two field quantities of √10:1.[13]

Two signals whose levels differ by one decibel have a power ratio of 101/10, which is approximately 1.25892, and an amplitude (field) ratio of 101/20 (1.12202).[14][15]

Although permissible, the bel is rarely used with other SI unit prefixes than deci. It is preferred to use hundredths of a decibel rather than millibels.[16]

The method of expressing a ratio as a level in decibels depends on whether the measured property is a power quantity or a field quantity; see Field, power, and root-power quantities for details.

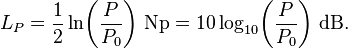

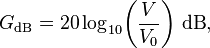

Power quantities

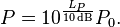

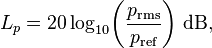

When referring to measurements of power quantities, a ratio can be expressed as a level in decibels by evaluating ten times the base-10 logarithm of the ratio of the measured quantity to reference value. Thus, the ratio of P (measured power) to P0 (reference power) is represented by LP, that ratio expressed in decibels,[17] which is calculated using the formula:[3]

The base-10 logarithm of the ratio of the two power levels is the number of bels. The number of decibels is ten times the number of bels (equivalently, a decibel is one-tenth of a bel). P and P0 must measure the same type of quantity, and have the same units before calculating the ratio. If P = P0 in the above equation, then LP = 0. If P is greater than P0 then LP is positive; if P is less than P0 then LP is negative.

Rearranging the above equation gives the following formula for P in terms of P0 and LP:

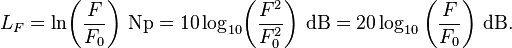

Field quantities and root-power quantities

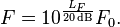

When referring to measurements of field quantities, it is usual to consider the ratio of the squares of F (measured field) and F0 (reference field). This is because in most applications power is proportional to the square of field, and it is desirable for the two decibel formulations to give the same result in such typical cases. Thus, the following definition is used:

The formula may be rearranged to give

Similarly, in electrical circuits, dissipated power is typically proportional to the square of voltage or current when the impedance is held constant. Taking voltage as an example, this leads to the equation:

where V is the voltage being measured, V0 is a specified reference voltage, and GdB is the power gain expressed in decibels. A similar formula holds for current.

The term root-power quantity is introduced by ISO Standard 80000-1:2009 as a substitute of field quantity. The term field quantity is deprecated by that standard.

Conversions

Since logarithm differences measured in these units are used to represent power ratios and field ratios, the values of the ratios represented by each unit are also included in the table.

| Unit | In decibels | In bels | In nepers | Corresponding power ratio | Corresponding field ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 dB | 1 dB | 0.1 B | 0.11513 Np | 101/10 ≈ 1.25893 | 101/20 ≈ 1.12202 |

| 1 B | 10 dB | 1 B | 1.1513 Np | 10 | 101/2 ≈ 3.16228 |

| 1 Np | 8.68589 dB | 0.868589 B | 1 Np | e2 ≈ 7.38906 | e ≈ 2.71828 |

Examples

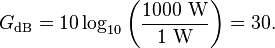

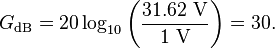

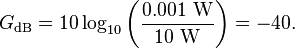

All of these examples yield dimensionless answers in dB because they are relative ratios expressed in decibels. The unit dBW is often used to denote a ratio for which the reference is 1 W, and similarly dBm for a 1 mW reference point.

- Calculating the ratio of 1 kW (one kilowatt, or 1000 watts) to 1 W in decibels yields:

- The ratio of √1000 V ≈ 31.62 V to 1 V in decibels is

(31.62 V/1 V)2 ≈ 1 kW/1 W, illustrating the consequence from the definitions above that GdB has the same value, 30, regardless of whether it is obtained from powers or from amplitudes, provided that in the specific system being considered power ratios are equal to amplitude ratios squared.

- The ratio of 1 mW (one milliwatt) to 10 W in decibels is obtained with the formula

- The power ratio corresponding to a 3 dB change in level is given by

A change in power ratio by a factor of 10 corresponds to a change in level of 10 dB. A change in power ratio by a factor of 2 is approximately a change of 3 dB. More precisely, the factor is 103/10, or 1.9953, about 0.24% different from exactly 2. Similarly, an increase of 3 dB implies an increase in voltage by a factor of approximately √2, or about 1.41, an increase of 6 dB corresponds to approximately four times the power and twice the voltage, and so on. In exact terms the power ratio is 106/10, or about 3.9811, a relative error of about 0.5%.

Properties

The decibel has the following properties:

- The logarithmic scale nature of the decibel means that a very large range of ratios can be represented by a convenient number, in a similar manner to scientific notation. This allows one to clearly visualize huge changes of some quantity. See Bode plot and semi-log plot. For example, 120 dB SPL may be clearer than "a trillion times more intense than the threshold of hearing".

- Level values in decibels can be added instead of multiplying the underlying power values, which means that the overall gain of a multi-component system, such as a series of amplifier stages, can be calculated by summing the gains in decibels of the individual components, rather than multiply the amplification factors; that is, log(A × B × C) = log(A) + log(B) + log(C). Practically, this means that, armed only with the knowledge that 1 dB is approximately 26% power gain, 3 dB is approximately 2× power gain, and 10 dB is 10× power gain, it is possible to determine the power ratio of a system from the gain in dB with only simple addition and multiplication. For example:

- A system consists of 3 amplifiers in series, with gains (ratio of power out to in) of 10 dB, 8 dB, and 7 dB respectively, for a total gain of 25 dB. Broken into combinations of 10, 3, and 1 dB, this is:

- 25 dB = 10 dB + 10 dB + 3 dB + 1 dB + 1 dB

- With an input of 1 watt, the output is approximately

- 1 W x 10 x 10 x 2 x 1.26 x 1.26 = ~317.5 W

- Calculated exactly, the output is 1 W x 1025/10 = 316.2 W. The approximate value has an error of only +0.4% with respect to the actual value which is negligible given the precision of the values supplied and the accuracy of most measurement instrumentation.

- A system consists of 3 amplifiers in series, with gains (ratio of power out to in) of 10 dB, 8 dB, and 7 dB respectively, for a total gain of 25 dB. Broken into combinations of 10, 3, and 1 dB, this is:

Advantages and disadvantages

Supporting arguments

According to Mitschke,[18] "The advantage of using a logarithmic measure is that in a transmission chain, there are many elements concatenated, and each has its own gain or attenuation. To obtain the total, addition of decibel values is much more convenient than multiplication of the individual factors."

The human perception of the intensity of sound and light approximates the logarithm of intensity rather than a linear relationship (Weber–Fechner law), making the dB scale a useful measure.[19][20][21][22][23][24]

Decibels are still the commonly used units to express ratios in a number of fields, even when the original meaning of the term is obscured. Decibels are the traditional way of expressing gain or margin in such diverse disciplines as control theory, antenna and radio frequency transmission theory, and even assessment of nuclear hardness.

Criticism

Various published articles have criticized the unit decibel as having shortcomings that hinder its understanding and use:[25][26][27] According to its critics, the decibel creates confusion, obscures reasoning, is more related to the era of slide rules than to modern digital processing, are cumbersome and difficult to interpret.[27]

Representing the equivalent of zero watts is not possible, causing problems in conversions. Hickling concludes "Decibels are a useless affectation, which is impeding the development of noise control as an engineering discipline".[27]

A common source of confusion in using the decibel occurs when deciding about the use of 10*log or 20*log. In the original definition, it was a power measurement, and as employed in that context, the formulation 10*log should be used, as deci means one tenth. The user must be clear whether the quantity expressed is power or amplitude. It is useful to consider how power or energy is expressed, e.g., current*current*resistance, 0.5*velocity*velocity*mass. if the formulation is a square function of the variable, then 20*log is the correct expression. In simple ratios without obvious power or energy context, such as damage ratios in nuclear hardness assessments, the 20*log is commonly used.

Quantities in decibels are not necessarily additive,[28][29] thus being "of unacceptable form for use in dimensional analysis".[30]

For the same reason that humans excel at additive operation over multiplication, decibels are awkward in inherently additive operations:[31] "if two machines each individually produce a [sound pressure] level of, say, 90 dB at a certain point, then when both are operating together we should expect the combined sound pressure level to increase to 93 dB, but certainly not to 180 dB!." "suppose that the noise from a machine is measured (including the contribution of background noise) and found to be 87 dBA but when the machine is switched off the background noise alone is measured as 83 dBA. ... the machine noise [level (alone)] may be obtained by 'subtracting' the 83 dBA background noise from the combined level of 87 dBA; i.e., 84.8 dBA." "in order to find a representative value of the sound level in a room a number of measurements are taken at different positions within the room, and an average value is calculated. (...) Compare the logarithmic and arithmetic averages of ... 70 dB and 90 dB: logarithmic average = 87 dB; arithmetic average = 80 dB."

Uses

Acoustics

The decibel is commonly used in acoustics as a unit of sound pressure level. The reference pressure in air is set at the typical threshold of perception of an average human and there are common comparisons used to illustrate different levels of sound pressure. Sound pressure is a field quantity, therefore the field version of the unit definition is used:

where pref is the standard reference sound pressure of 20 micropascals in air[32] or 1 micropascal in water.

The human ear has a large dynamic range in sound reception. The ratio of the sound intensity that causes permanent damage during short exposure to the quietest sound that the ear can hear is greater than or equal to 1 trillion (1012).[33] Such large measurement ranges are conveniently expressed in logarithmic scale: the base-10 logarithm of 1012 is 12, which is expressed as a sound pressure level of 120 dB re 20 micropascals. Since the human ear is not equally sensitive to all sound frequencies, noise levels at maximum human sensitivity, somewhere between 2 and 4 kHz, are factored more heavily into some measurements using frequency weighting. (See also Stevens' power law.)

Electronics

In electronics, the decibel is often used to express power or amplitude ratios (gains), in preference to arithmetic ratios or percentages. One advantage is that the total decibel gain of a series of components (such as amplifiers and attenuators) can be calculated simply by summing the decibel gains of the individual components. Similarly, in telecommunications, decibels denote signal gain or loss from a transmitter to a receiver through some medium (free space, waveguide, coaxial cable, fiber optics, etc.) using a link budget.

The decibel unit can also be combined with a suffix to create an absolute unit of electric power. For example, it can be combined with "m" for "milliwatt" to produce the "dBm". Zero dBm is the level corresponding to one milliwatt, and 1 dBm is one decibel greater (about 1.259 mW).

In professional audio specifications, a popular unit is the dBu. The dBu is a root mean square (RMS) measurement of voltage that uses as its reference approximately 0.775 VRMS. Chosen for historical reasons, the reference value is the voltage level which delivers 1 mW of power in a 600 ohm resistor, which used to be the standard reference impedance in telephone circuits.

Optics

In an optical link, if a known amount of optical power, in dBm (referenced to 1 mW), is launched into a fiber, and the losses, in dB (decibels), of each component (e.g., connectors, splices, and lengths of fiber) are known, the overall link loss may be quickly calculated by addition and subtraction of decibel quantities.[34]

In spectrometry and optics, the blocking unit used to measure optical density is equivalent to −1 B.

Video and digital imaging

In connection with video and digital image sensors, decibels generally represent ratios of video voltages or digitized light levels, using 20 log of the ratio, even when the represented optical power is directly proportional to the voltage or level, not to its square, as in a CCD imager where response voltage is linear in intensity.[35] Thus, a camera signal-to-noise ratio or dynamic range of 40 dB represents a power ratio of 100:1 between signal power and noise power, not 10,000:1.[36] Sometimes the 20 log ratio definition is applied to electron counts or photon counts directly, which are proportional to intensity without the need to consider whether the voltage response is linear.[37]

However, as mentioned above, the 10 log intensity convention prevails more generally in physical optics, including fiber optics, so the terminology can become murky between the conventions of digital photographic technology and physics. Most commonly, quantities called "dynamic range" or "signal-to-noise" (of the camera) would be specified in 20 log dBs, but in related contexts (e.g. attenuation, gain, intensifier SNR, or rejection ratio) the term should be interpreted cautiously, as confusion of the two units can result in very large misunderstandings of the value.

Photographers typically use an alternative base-2 log unit, the f-stop, to describe light intensity or dynamic range.

Suffixes and reference values

Suffixes are commonly attached to the basic dB unit in order to indicate the reference value by which the ratio is calculated. For example, dBm indicates power measurement relative to 1 milliwatt.

In cases where the unit value of the reference is stated, the decibel value is known as "absolute". If the unit value of the reference is not explicitly stated, as in the dB gain of an amplifier, then the decibel value is considered relative.

The SI does not permit attaching qualifiers to units, whether as suffix or prefix, other than standard SI prefixes. Therefore, even though the decibel is accepted for use alongside SI units, the practice of attaching a suffix to the basic dB unit, forming compound units such as dBm, dBu, dBA, etc., is not.[12] The proper way, according to the IEC 60027-3,[11] is either as Lx (re xref) or as Lx/xref, where x is the quantity symbol and xref is the value of the reference quantity, e.g., LE (re 1 μV/m) = LE/(1 μV/m) for the electric field strength E relative to 1 μV/m reference value.

Outside of documents adhering to SI units, the practice is very common as illustrated by the following examples. There is no general rule, with various discipline-specific practices. Sometimes the suffix is a unit symbol ("W","K","m"), sometimes it is a transliteration of a unit symbol ("uV" instead of μV for microvolt), sometimes it is an acronym for the unit's name ("sm" for square meter, "m" for milliwatt), other times it is a mnemonic for the type of quantity being calculated ("i" for antenna gain with respect to an isotropic antenna, "λ" for anything normalized by the EM wavelength), or otherwise a general attribute or identifier about the nature of the quantity ("A" for A-weighted sound pressure level). The suffix is often connected with a dash (dB-Hz), with a space (dB HL), with no intervening character (dBm), or enclosed in parentheses, dB(sm).

Voltage

Since the decibel is defined with respect to power, not amplitude, conversions of voltage ratios to decibels must square the amplitude, or use the factor of 20 instead of 10, as discussed above.

dBV

dBu or dBv

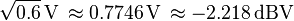

- RMS voltage relative to

.[2] Originally dBv, it was changed to dBu to avoid confusion with dBV.[38] The "v" comes from "volt", while "u" comes from "unloaded". dBu can be used regardless of impedance, but is derived from a 600 Ω load dissipating 0 dBm (1 mW). The reference voltage comes from the computation

.[2] Originally dBv, it was changed to dBu to avoid confusion with dBV.[38] The "v" comes from "volt", while "u" comes from "unloaded". dBu can be used regardless of impedance, but is derived from a 600 Ω load dissipating 0 dBm (1 mW). The reference voltage comes from the computation  .

.

- In professional audio, equipment may be calibrated to indicate a "0" on the VU meters some finite time after a signal has been applied at an amplitude of +4 dBu. Consumer equipment typically uses a lower "nominal" signal level of -10 dBV.[39] Therefore, many devices offer dual voltage operation (with different gain or "trim" settings) for interoperability reasons. A switch or adjustment that covers at least the range between +4 dBu and -10 dBV is common in professional equipment.

dBmV

- dB(mVRMS) – voltage relative to 1 millivolt across 75 Ω.[40] Widely used in cable television networks, where the nominal strength of a single TV signal at the receiver terminals is about 0 dBmV. Cable TV uses 75 Ω coaxial cable, so 0 dBmV corresponds to −78.75 dBW (−48.75 dBm) or ~13 nW.

dBμV or dBuV

- dB(μVRMS) – voltage relative to 1 microvolt. Widely used in television and aerial amplifier specifications. 60 dBμV = 0 dBmV.

Acoustics

Probably the most common usage of "decibels" in reference to sound level is dB SPL, sound pressure level referenced to the nominal threshold of human hearing:[41] The measures of pressure (a field quantity) use the factor of 20, and the measures of power (e.g. dB SIL and dB SWL) use the factor of 10.

dB SPL

- dB SPL (sound pressure level) – for sound in air and other gases, relative to 20 micropascals (μPa) = 2×10−5 Pa, approximately the quietest sound a human can hear. For sound in water and other liquids, a reference pressure of 1 μPa is used.[42]

An RMS sound pressure of one pascal corresponds to a level of 94 dB SPL.

dB SIL

- dB sound intensity level – relative to 10−12 W/m2, which is roughly the threshold of human hearing in air.

dB SWL

- dB sound power level – relative to 10−12 W.

dB(A), dB(B), and dB(C)

- These symbols are often used to denote the use of different weighting filters, used to approximate the human ear's response to sound, although the measurement is still in dB (SPL). These measurements usually refer to noise and its effects on humans and animals, and they are widely used in industry while discussing noise control issues, regulations and environmental standards. Other variations that may be seen are dBA or dBA. According to ANSI standards, the preferred usage is to write LA = x dB. Nevertheless, the units dBA and dB(A) are still commonly used as a shorthand for A-weighted measurements. Compare dBc, used in telecommunications.

dB HL or dB hearing level is used in audiograms as a measure of hearing loss. The reference level varies with frequency according to a minimum audibility curve as defined in ANSI and other standards, such that the resulting audiogram shows deviation from what is regarded as 'normal' hearing.

dB Q is sometimes used to denote weighted noise level, commonly using the ITU-R 468 noise weighting

Audio electronics

- dB(mW) – power relative to 1 milliwatt. In audio and telephony, dBm is typically referenced relative to a 600 ohm impedance,[43] while in radio frequency work dBm is typically referenced relative to a 50 ohm impedance.[44]

- dB(full scale) – the amplitude of a signal compared with the maximum which a device can handle before clipping occurs. Full-scale may be defined as the power level of a full-scale sinusoid or alternatively a full-scale square wave. A signal measured with reference to a full-scale sine-wave will appear 3dB weaker when referenced to a full-scale square wave, thus: 0 dBFS(ref=fullscale sine wave) = -3 dBFS(ref=fullscale square wave).

dBTP

- dB(true peak) - peak amplitude of a signal compared with the maximum which a device can handle before clipping occurs.[45] In digital systems, 0 dBTP would equal the highest level (number) the processor is capable of representing. Measured values are always negative or zero, since they are less than or equal to full-scale.

Radar

- dB(Z) – decibel relative to Z = 1 mm6 m−3:[46] energy of reflectivity (weather radar), related to the amount of transmitted power returned to the radar receiver. Values above 15–20 dBZ usually indicate falling precipitation.[47]

dBsm

- dB(m2) – decibel relative to one square meter: measure of the radar cross section (RCS) of a target. The power reflected by the target is proportional to its RCS. "Stealth" aircraft and insects have negative RCS measured in dBsm, large flat plates or non-stealthy aircraft have positive values.[48]

Radio power, energy, and field strength

- dBc

- dBc – relative to carrier—in telecommunications, this indicates the relative levels of noise or sideband power, compared with the carrier power. Compare dBC, used in acoustics.

- dBJ

- dB(J) – energy relative to 1 joule. 1 joule = 1 watt second = 1 watt per hertz, so power spectral density can be expressed in dBJ.

- dBm

- dB(mW) – power relative to 1 milliwatt. Traditionally associated with the telephone and broadcasting industry to express audio-power levels referenced to one milliwatt of power, normally with a 600 ohm load, which is a voltage level of 0.775 volts or 775 millivolts. This is still commonly used to express audio levels with professional audio equipment.

- In the radio field, dBm is usually referenced to a 50 ohm load, with the resultant voltage being 0.224 volts.

- dBμV/m or dBuV/m

- dB(μV/m) – electric field strength relative to 1 microvolt per meter. Often used to specify the signal strength from a television broadcast at a receiving site (the signal measured at the antenna output will be in dBμV).

- dBf

- dB(fW) – power relative to 1 femtowatt.

- dBW

- dB(W) – power relative to 1 watt.

- dBk

- dB(kW) – power relative to 1 kilowatt.

Antenna measurements

dBi

- dB(isotropic) – the forward gain of an antenna compared with the hypothetical isotropic antenna, which uniformly distributes energy in all directions. Linear polarization of the EM field is assumed unless noted otherwise.

dBd

- dB(dipole) – the forward gain of an antenna compared with a half-wave dipole antenna. 0 dBd = 2.15 dBi

dBiC

- dB(isotropic circular) – the forward gain of an antenna compared to a circularly polarized isotropic antenna. There is no fixed conversion rule between dBiC and dBi, as it depends on the receiving antenna and the field polarization.

dBq

- dB(quarterwave) – the forward gain of an antenna compared to a quarter wavelength whip. Rarely used, except in some marketing material. 0 dBq = −0.85 dBi

dBsm

- dB(m2) – decibel relative to one square meter: measure of the antenna effective area.[49]

dBm−1

- dB(m−1) – decibel relative to reciprocal of meter: measure of the antenna factor.

Other measurements

dB-Hz

- dB(Hz) – bandwidth relative to one hertz. E.g., 20 dB-Hz corresponds to a bandwidth of 100 Hz. Commonly used in link budget calculations. Also used in carrier-to-noise-density ratio (not to be confused with carrier-to-noise ratio, in dB).

dBov or dBO

- dB(overload) – the amplitude of a signal (usually audio) compared with the maximum which a device can handle before clipping occurs. Similar to dBFS, but also applicable to analog systems.

dBr

- dB(relative) – simply a relative difference from something else, which is made apparent in context. The difference of a filter's response to nominal levels, for instance.

- dB above reference noise. See also dBrnC

dBrnC

- dBrnC represents an audio level measurement, typically in a telephone circuit, relative to the circuit noise level, with the measurement of this level frequency-weighted by a standard C-message weighting filter. The C-message weighting filter was chiefly used in North America. The Psophometric filter is used for this purpose on international circuits. See Psophometric weighting to see a comparison of frequency response curves for the C-message weighting and Psophometric weighting filters.[50]

dBK

- dB(K) – decibels relative to kelvin: Used to express noise temperature.[51]

dB/K

- dB(K−1) – decibels relative to reciprocal of kelvin[52]—not decibels per kelvin: Used for the G/T factor, a figure of merit utilized in satellite communications, relating the antenna gain G to the receiver system noise equivalent temperature T.[53][54]

Related units

- mBm

- mB(mW) – power relative to 1 milliwatt, in millibels (one hundredth of a decibel). 100 mBm = 1dBm. This unit is in the Wi-Fi drivers of the Linux kernel[55] and the regulatory domain sections.[56]

Np or cNp

- Another closely related unit is the neper (Np) or centineper (cNp). Like the decibel, the neper is a unit of level.[3] The linear approximation 1cNp =~ 1% for small percentage differences is widely used finance.

Fractions

Attenuation constants, in fields such as optical fiber communication and radio propagation path loss, are often expressed as a fraction or ratio to distance of transmission. dB/m means decibels per meter, dB/mi is decibels per mile, for example. These quantities are to be manipulated obeying the rules of dimensional analysis, e.g., a 100-meter run with a 3.5 dB/km fiber yields a loss of 0.35 dB = 3.5 dB/km × 0.1 km.

See also

- Apparent magnitude

- Cent (music)

- dB drag racing

- Decade (log scale)

- Equal-loudness contour

- Noise (environmental)

- Phon

- Richter magnitude scale

- Signal noise

- Sone

- pH

Notes and references

- ↑ IEEE Standard 100 Dictionary of IEEE Standards Terms, Seventh Edition, The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineering, New York, 2000; ISBN 0-7381-2601-2; page 288

- 1 2 3 Analog Devices : Virtual Design Center : Interactive Design Tools : Utilities : VRMS / dBm / dBu / dBV calculator

- 1 2 3 "ISO 80000-3:2006". International Organization for Standardization. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ Johnson, Kenneth Simonds (1944). Transmission Circuits for Telephonic Communication: Methods of Analysis and Design. New York: D. Van Nostrand Co. p. 10.

- ↑ Don Davis and Carolyn Davis (1997). Sound system engineering (2nd ed.). Focal Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-240-80305-0.

- ↑ R. V. L. Hartley (Dec 1928). "'TU' becomes 'Decibel'". Bell Laboratories Record (AT&T) 7 (4): 137–139.

- ↑ Martin, W. H. (January 1929). "DeciBel—The New Name for the Transmission Unit". Bell System Technical Journal 8 (1).

- ↑ 100 Years of Telephone Switching, p. 276, at Google Books, Robert J. Chapuis, Amos E. Joel, 2003

- ↑ William H. Harrison (1931). "Standards for Transmission of Speech". Standards Yearbook (National Bureau of Standards, U. S. Govt. Printing Office) 119

- ↑ Consultative Committee for Units, Meeting minutes, Section 3

- 1 2 "Letter symbols to be used in electrical technology – Part 3: Logarithmic and related quantities, and their units", IEC 60027-3 Ed. 3.0, International Electrotechnical Commission, 19 July 2002.

- 1 2 Thompson, A. and Taylor, B. N. sec 8.7, "Logarithmic quantities and units: level, neper, bel", Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) 2008 Edition, NIST Special Publication 811, 2nd printing (November 2008), SP811 PDF

- ↑ "International Standard CEI-IEC 27-3 Letter symbols to be used in electrical technology Part 3: Logarithmic quantities and units". International Electrotechnical Commission.

- ↑ Mark, James E. (2007). Physical Properties of Polymers Handbook. Springer. p. 1025.

… the decibel represents a reduction in power of 1.258 times.

- ↑ Yost, William (1985). Fundamentals of Hearing: An Introduction (Second ed.). Holt, Rinehart and Winston. p. 206. ISBN 0-12-772690-X.

… a pressure ratio of 1.122 equals + 1.0 dB

- ↑ Fedor Mitschke, Fiber Optics: Physics and Technology, Springer, 2010 ISBN 3642037038.

- ↑ David M. Pozar (2005). Microwave Engineering (3rd ed.). Wiley. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-471-44878-5.

- ↑ Fiber Optics. Springer. 2010.

- ↑ Sensation and Perception, p. 268, at Google Books

- ↑ Introduction to Understandable Physics, Volume 2, p. SA19-PA9, at Google Books

- ↑ Visual Perception: Physiology, Psychology, and Ecology, p. 356, at Google Books

- ↑ Exercise Psychology, p. 407, at Google Books

- ↑ Foundations of Perception, p. 83, at Google Books

- ↑ Fitting The Task To The Human, p. 304, at Google Books

- ↑ C W Horton, "The bewildering decibel" Elec. Eng., 73, 550-555 (1954)

- ↑ C S Clay (1999), Underwater sound transmission and SI units, J Acoust Soc Am 106, 3047

- 1 2 3 R Hickling (1999), Noise Control and SI Units, J Acoust Soc Am 106, 3048

- ↑ Nicholas P. Cheremisinoff (1996) Noise Control in Industry: A Practical Guide, Elsevier, 203 pp, p. 7

- ↑ Andrew Clennel Palmer (2008), Dimensional Analysis and Intelligent Experimentation, World Scientific, 154 pp, p.13

- ↑ J.C. Gibbings, Dimensional Analysis, p.37, Springer, 2011 ISBN 1849963177.

- ↑ R J Peters, Acoustics and Noise Control, Routledge, Nov 12, 2013, 400 pages, p.13

- ↑ "Electronic Engineer's Handbook" by Donald G. Fink, Editor-in-Chief ISBN 0-07-020980-4 Published by McGraw Hill, page 19-3

- ↑ National Institute on Deafness and Other Communications Disorders, Noise-Induced Hearing Loss (National Institutes of Health, 2008).

- ↑ Bob Chomycz (2000). Fiber optic installer's field manual. McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 123–126. ISBN 978-0-07-135604-6.

- ↑ Stephen J. Sangwine and Robin E. N. Horne (1998). The Colour Image Processing Handbook. Springer. pp. 127–130. ISBN 978-0-412-80620-9.

- ↑ Francis T. S. Yu and Xiangyang Yang (1997). Introduction to optical engineering. Cambridge University Press. pp. 102–103. ISBN 978-0-521-57493-8.

- ↑ Junichi Nakamura (2006). "Basics of Image Sensors". In Junichi Nakamura. Image sensors and signal processing for digital still cameras. CRC Press. pp. 79–83. ISBN 978-0-8493-3545-7.

- ↑ What is the difference between dBv, dBu, dBV, dBm, dB SPL, and plain old dB? Why not just use regular voltage and power measurements? – rec.audio.pro Audio Professional FAQ

- ↑ deltamedia.com. "DB or Not DB". Deltamedia.com. Retrieved 2013-09-16.

- ↑ The IEEE Standard Dictionary of Electrical and Electronics terms (6th ed.). IEEE. 1996 [1941]. ISBN 1-55937-833-6.

- ↑ Jay Rose (2002). Audio postproduction for digital video. Focal Press,. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-57820-116-7.

- ↑ Morfey, C. L. (2001). Dictionary of Acoustics. Academic Press, San Diego.

- ↑ Bigelow, Stephen. Understanding Telephone Electronics. Newnes. p. 16. ISBN 978-0750671750.

- ↑ Carr, Joseph (2002). RF Components and Circuits. Newnes. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-0750648448.

- ↑ ITU-R BS.1770

- ↑ "Glossary: D's". National Weather Service. Retrieved 2013-04-25.

- ↑ "Radar FAQ from WSI". Archived from the original on 2008-05-18. Retrieved 2008-03-18.

- ↑ "Definition at Everything2". Retrieved 2008-08-06.

- ↑ David Adamy. EW 102: A Second Course in Electronic Warfare. Retrieved 2013-09-16.

- ↑ dBrnC is defined on page 230 in "Engineering and Operations in the Bell System," (2ed), R.F. Rey (technical editor), copyright 1983, AT&T Bell Laboratories, Murray Hill, NJ, ISBN 0-932764-04-5

- ↑ K. N. Raja Rao (2013-01-31). Satellite Communication: Concepts And Applications. Retrieved 2013-09-16.

- ↑ Ali Akbar Arabi. Comprehensive Glossary of Telecom Abbreviations and Acronyms. Retrieved 2013-09-16.

- ↑ Mark E. Long. The Digital Satellite TV Handbook. Retrieved 2013-09-16.

- ↑ Mac E. Van Valkenburg (2001-10-19). Reference Data for Engineers: Radio, Electronics, Computers and Communications. Retrieved 2013-09-16.

- ↑ setting the TX power for a Wi-Fi device in Linux showing units in mBm

- ↑ kernel notification of change in regulatory domain showing units in mBm

External links

- What is a decibel? With sound files and animations

- Conversion of sound level units: dBSPL or dBA to sound pressure p and sound intensity J

- OSHA Regulations on Occupational Noise Exposure

| ||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|