Gudermannian function

The Gudermannian function, named after Christoph Gudermann (1798–1852), relates the circular functions and hyperbolic functions without using complex numbers.

Properties

Alternative definitions

Some related formula, such as  , doesn't quite work as definition. (See inverse trigonometric functions.)

, doesn't quite work as definition. (See inverse trigonometric functions.)

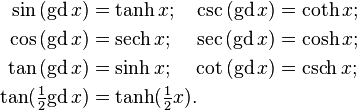

Some identities

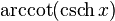

Inverse

(See inverse hyperbolic functions.)

Some identities

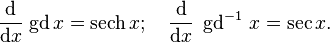

Derivatives

History

The function was introduced by Johann Heinrich Lambert in the 1760s at the same time as the hyperbolic functions. He called it the "transcendent angle," and it went by various names until 1862 when Arthur Cayley suggested it be given its current name as a tribute to Gudermann's work in the 1830s on the theory of special functions.[4] Gudermann had published articles in Crelle's Journal that were collected in Theorie der potenzial- oder cyklisch-hyperbolischen Functionen (1833), a book which expounded sinh and cosh to a wide audience (under the guises of  and

and  ).

).

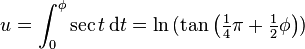

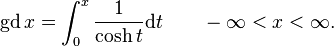

The notation gd was introduced by Cayley[5] where he starts by calling gd. u the inverse of the integral of the secant function:

and then derives "the definition" of the transcendent:

observing immediately that it is a real function of u.

Applications

- The angle of parallelism function in hyperbolic geometry is defined by

- On a Mercator projection a line of constant latitude is parallel to the equator (on the projection) and is displaced by an amount proportional to the inverse Gudermannian of the latitude.

- The Gudermannian (with a complex argument) may be used in the definition of the Transverse Mercator projection.[6]

- The Gudermannian appears in a non-periodic solution of the inverted pendulum.[7]

- The Gudermannian also appears in a moving mirror solution of the dynamical Casimir effect.[8]

References

- ↑ Olver, F. W.J.; Lozier, D.W.; Boisvert, R.F.; Clark, C.W., eds. (2010), NIST Handbook of Mathematical Functions, Cambridge University Press. Section 4.23(viii).

- ↑ CRC Handbook of Mathematical Sciences 5th ed. pp. 323–325

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W., "Gudermannian", MathWorld.

- ↑ George F. Becker, C. E. Van Orstrand. Hyperbolic functions. Read Books, 1931. Page xlix. Scanned copy available at archive.org

- ↑ Cayley, A. (1862). "On the transcendent gd. u". Philosophical Magazine (4th ser.) 24: 19–21. doi:10.1080/14786446208643307 (inactive 2015-02-01).

- ↑ Osborne, P (2013), The Mercator projections, p74

- ↑ John S. Robertson (1997). "Gudermann and the Simple Pendulum". The College Mathematics Journal 28 (4): 271–276. JSTOR 2687148. Review.

- ↑ Good, Michael R. R.; Anderson, Paul R.; Evans, Charles R. (2013). "Time dependence of particle creation from accelerating mirrors". Physical Review D 88 (2): 025023. arXiv:1303.6756. Bibcode:2013PhRvD..88b5023G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.88.025023.

See also

- Hyperbolic secant distribution

- Mercator projection

- Tangent half-angle formula

- Tractrix

- Trigonometric identity

![\begin{align}{\rm{gd}}\,x

&=\arcsin\left(\tanh x \right)=\mathrm{arctan}\left(\sinh x \right)=\mathrm{arccsc}\left(\coth x \right) \\

&=\mbox{sgn}(x)\cdot\mathrm{arccos}\left(\mathrm{sech}\,x \right)=\mbox{sgn}(x)\cdot\mathrm{arcsec}\left(\cosh x \right) \\

&=2\,\arctan\left[\tanh\left(\tfrac12x\right)\right]\\

&=2\,\arctan(e^x)-\tfrac12\pi.

\end{align}\,\!](../I/m/ab53f7bdc4fb23a2d2f135937d4a22cd.png)

![\begin{align}

\operatorname{gd}^{-1}\,x

& = \int_0^x\frac{1}{\cos t}\mathrm{d}t \qquad -\pi/2<x<\pi/2\\[8pt]

& = \ln\left| \frac{1 + \sin x}{\cos x} \right| = \tfrac12\ln \left| \frac{1 + \sin x}{1 - \sin x} \right| \\[8pt]

& = \ln\left| \tan x +\sec x \right| = \ln \left| \tan\left(\tfrac14\pi + \tfrac12x\right) \right| \\[8pt]

& = \mathrm{arctanh}\,(\sin x) = \mathrm{arcsinh}\,(\tan x)\\

& = \mathrm{arccoth}\,(\csc x) = \mathrm{arccsch}\,(\cot x)\\

& = \mbox{sgn}(x)\,\mathrm{arccosh}\,(\sec x) = \mbox{sgn}(x)\,\mathrm{arcsech}\,(\cos x)\\

& = -i \operatorname{gd}(ix)

\end{align}](../I/m/2baa8feeff20703d3ee972a16f2fd450.png)