Tournament (graph theory)

| Tournament | |

|---|---|

|

A tournament on 4 vertices | |

| Vertices |

|

| Edges |

|

A tournament is a directed graph (digraph) obtained by assigning a direction for each edge in an undirected complete graph. That is, it is an orientation of a complete graph, or equivalently a directed graph in which every pair of distinct vertices is connected by a single directed edge.

Many of the important properties of tournaments were first investigated by Landau in order to model dominance relations in flocks of chickens. Current applications of tournaments include the study of voting theory and social choice theory among other things. The name tournament originates from such a graph's interpretation as the outcome of a round-robin tournament in which every player encounters every other player exactly once, and in which no draws occur. In the tournament digraph, the vertices correspond to the players. The edge between each pair of players is oriented from the winner to the loser. If player  beats player

beats player  , then it is said that

, then it is said that  dominates

dominates  .

.

Paths and cycles

Any tournament on a finite number  of vertices contains a Hamiltonian path, i.e., directed path on all

of vertices contains a Hamiltonian path, i.e., directed path on all  vertices (Rédei 1934). This is easily shown by induction on

vertices (Rédei 1934). This is easily shown by induction on  : suppose that the statement holds for

: suppose that the statement holds for  , and consider any tournament

, and consider any tournament  on

on  vertices. Choose a vertex

vertices. Choose a vertex  of

of  and consider a directed path

and consider a directed path  in

in  . Now let

. Now let  be maximal such that for every

be maximal such that for every  there is a directed edge from

there is a directed edge from  to

to  .

.

is a directed path as desired. This argument also gives an algorithm for finding the Hamiltonian path. More efficient algorithms, that require examining only  of the edges, are known.[1]

of the edges, are known.[1]

This implies that a strongly connected tournament has a Hamiltonian cycle (Camion 1959). More strongly, every strongly connected tournament is vertex pancyclic: for each vertex v, and each k in the range from three to the number of vertices in the tournament, there is a cycle of length k containing v.[2] Moreover, if the tournament is 4‑connected, each pair of vertices can be connected with a Hamiltonian path (Thomassen 1980).

Transitivity

A tournament in which  and

and

is called transitive. In a transitive tournament, the vertices may be totally ordered by reachability.

is called transitive. In a transitive tournament, the vertices may be totally ordered by reachability.

Equivalent conditions

The following statements are equivalent for a tournament T on n vertices:

- T is transitive.

- T is acyclic.

- T does not contain a cycle of length 3.

- The score sequence (set of outdegrees) of T is {0,1,2,...,n − 1}.

- T has exactly one Hamiltonian path.

Ramsey theory

Transitive tournaments play a role in Ramsey theory analogous to that of cliques in undirected graphs. In particular, every tournament on n vertices contains a transitive subtournament on  vertices.[3] The proof is simple: choose any one vertex v to be part of this subtournament, and form the rest of the subtournament recursively on either the set of incoming neighbors of v or the set of outgoing neighbors of v, whichever is larger. For instance, every tournament on seven vertices contains a three-vertex transitive subtournament; the Paley tournament on seven vertices shows that this is the most that can be guaranteed (Erdős & Moser 1964).

However, Reid & Parker (1970) showed that this bound is not tight for some larger values of n.

vertices.[3] The proof is simple: choose any one vertex v to be part of this subtournament, and form the rest of the subtournament recursively on either the set of incoming neighbors of v or the set of outgoing neighbors of v, whichever is larger. For instance, every tournament on seven vertices contains a three-vertex transitive subtournament; the Paley tournament on seven vertices shows that this is the most that can be guaranteed (Erdős & Moser 1964).

However, Reid & Parker (1970) showed that this bound is not tight for some larger values of n.

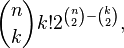

Erdős & Moser (1964) proved that there are tournaments on n vertices without a transitive subtournament of size  Their proof uses a counting argument: the number of ways that a k-element transitive tournament can occur as a subtournament of a larger tournament on n labeled vertices is

Their proof uses a counting argument: the number of ways that a k-element transitive tournament can occur as a subtournament of a larger tournament on n labeled vertices is

and when k is larger than  , this number is too small to allow for an occurrence of a transitive tournament within each of the

, this number is too small to allow for an occurrence of a transitive tournament within each of the  different tournaments on the same set of n labeled vertices.

different tournaments on the same set of n labeled vertices.

Paradoxical tournaments

A player who wins all games would naturally be the tournament's winner. However, as the existence of non-transitive tournaments shows, there may not be such a player. A tournament for which every player loses at least one game is called a 1-paradoxical tournament. More generally, a tournament T=(V,E) is called k-paradoxical if for every k-element subset S of V there is a vertex v0 in  such that

such that  for all

for all  . By means of the probabilistic method, Paul Erdős showed that for any fixed value of k, if |V| ≥ k22kln(2 + o(1)), then almost every tournament on V is k-paradoxical.[4] On the other hand, an easy argument shows that any k-paradoxical tournament must have at least 2k+1 − 1 players, which was improved to (k + 2)2k−1 − 1 by Esther and George Szekeres (1965). There is an explicit construction of k-paradoxical tournaments with k24k−1(1 + o(1)) players by Graham and Spencer (1971) namely the Paley tournament.

. By means of the probabilistic method, Paul Erdős showed that for any fixed value of k, if |V| ≥ k22kln(2 + o(1)), then almost every tournament on V is k-paradoxical.[4] On the other hand, an easy argument shows that any k-paradoxical tournament must have at least 2k+1 − 1 players, which was improved to (k + 2)2k−1 − 1 by Esther and George Szekeres (1965). There is an explicit construction of k-paradoxical tournaments with k24k−1(1 + o(1)) players by Graham and Spencer (1971) namely the Paley tournament.

Condensation

The condensation of any tournament is itself a transitive tournament. Thus, even for tournaments that are not transitive, the strongly connected components of the tournament may be totally ordered.[5]

Score sequences and score sets

The score sequence of a tournament is the nondecreasing sequence of outdegrees of the vertices of a tournament. The score set of a tournament is the set of integers that are the outdegrees of vertices in that tournament.

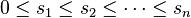

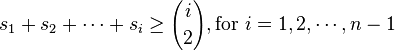

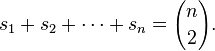

Landau's Theorem (1953) A nondecreasing sequence of integers  is a score sequence if and only if :

is a score sequence if and only if :

Let  be the number of different score sequences of size

be the number of different score sequences of size  . The sequence

. The sequence  (sequence A000571 in OEIS) starts as:

(sequence A000571 in OEIS) starts as:

1, 1, 1, 2, 4, 9, 22, 59, 167, 490, 1486, 4639, 14805, 48107, ...

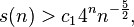

Winston and Kleitman proved that for sufficiently large n:

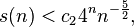

where  Takács later showed, using some reasonable but unproven assumptions, that

Takács later showed, using some reasonable but unproven assumptions, that

where

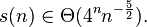

Together these provide evidence that:

Here  signifies an asymptotically tight bound.

signifies an asymptotically tight bound.

Yao showed that every nonempty set of nonnegative integers is the score set for some tournament.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Bar-Noy & Naor (1990).

- ↑ Moon (1966), Theorem 1.

- ↑ Erdős & Moser (1964).

- ↑ Erdős (1963).

- ↑ Harary & Moser (1966), Corollary 5b.

References

- Bar-Noy, A.; Naor, J. (1990), "Sorting, Minimal Feedback Sets and Hamilton Paths in Tournaments", SIAM Journal on Discrete Mathematics 3 (1): 7–20, doi:10.1137/0403002.

- Camion, Paul (1959), "Chemins et circuits hamiltoniens des graphes complets", Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences de Paris 249: 2151–2152.

- Erdős, P. (1963), "On a problem in graph theory" (PDF), The Mathematical Gazette 47: 220–223, JSTOR 3613396, MR 0159319.

- Erdős, P.; Moser, L. (1964), "On the representation of directed graphs as unions of orderings" (PDF), Magyar Tud. Akad. Mat. Kutató Int. Közl. 9: 125–132, MR 0168494.

- Graham, R. L.; Spencer, J. H. (1971), "A constructive solution to a tournament problem", Canadian Mathematical Bulletin 14: 45–48, doi:10.4153/cmb-1971-007-1, MR 0292715.

- Harary, Frank; Moser, Leo (1966), "The theory of round robin tournaments", American Mathematical Monthly 73 (3): 231–246, doi:10.2307/2315334, JSTOR 2315334.

- Landau, H.G. (1953), "On dominance relations and the structure of animal societies. III. The condition for a score structure", Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics 15 (2): 143–148, doi:10.1007/BF02476378.

- Moon, J. W. (1966), "On subtournaments of a tournament", Canadian Mathematical Bulletin 9 (3): 297–301, doi:10.4153/CMB-1966-038-7.

- Rédei, László (1934), "Ein kombinatorischer Satz", Acta Litteraria Szeged 7: 39–43.

- Reid, K.B.; Parker, E.T. (1970), "Disproof of a conjecture of Erdös and Moser", Journal of Combinatorial Theory 9 (3): 225–238, doi:10.1016/S0021-9800(70)80061-8.

- Szekeres, E.; Szekeres, G. (1965), "On a problem of Schütte and Erdős", The Mathematical Gazette 49: 290–293, doi:10.2307/3612854, MR 0186566.

- Takács, Lajos (1991), "A Bernoulli Excursion and Its Various Applications", Advances in Applied Probability (Applied Probability Trust) 23 (3): 557–585, doi:10.2307/1427622, JSTOR 1427622.

- Thomassen, Carsten (1980), "Hamiltonian-Connected Tournaments", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B 28 (2): 142–163, doi:10.1016/0095-8956(80)90061-1.

- Yao, T.X. (1989), "On Reid conjecture of score sets for tournaments", Chinese Sci. Bull. 34: 804–808.

This article incorporates material from tournament on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.