Torrs Pony-cap and Horns

The Torrs Horns and Torrs Pony-cap (once together known as the Torrs Chamfrein) are Iron Age bronze pieces now in the National Museum of Scotland, which were found together, but whose relationship is one of many questions about these "famous and controversial" objects that continue to be debated by scholars. Most scholars agree that horns were added to the pony-cap at a later date, but whether they were originally made for this purpose is unclear; one theory sees them as mounts for drinking-horns, either totally or initially unconnected to the cap. The three pieces are decorated in a late stage of La Tène style, as Iron Age Celtic art is called by archaeologists. The dates ascribed to the elements vary, but are typically around 200 BC; it is generally agreed that the horns are somewhat later than the cap, and in a rather different style.[1]

Whatever the original appearance and functions of the objects, and wherever they were made, they are very finely designed and skillfully executed, and form part of a small surviving group of elaborate metal objects found around the British Isles that were commissioned by the elite of Iron Age British and Irish society in the final centuries before the arrival of the Romans.[2]

Modern history

The artefacts were found together, "about 1820" and "before 1829",[3] in a peat bog at Torrs Farm, Kelton, Kirkcudbright, Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland, the context suggesting they were a votive deposit (the bog may once have been a pool or lake). It was thought that the horns were detached from the cap at finding, but a recently unearthed contemporary newspaper report says they were attached. They were given by the local exciseman to the novelist Sir Walter Scott, and long displayed with the horns attached to the cap at Abbotsford House, which was opened for public visits from 1833, soon after Scott's death.[4] The horns are currently exhibited fixed onto the cap, pointing backwards, but were originally mounted pointing forwards,[5] and have also been displayed detached from the cap.[6]

Description

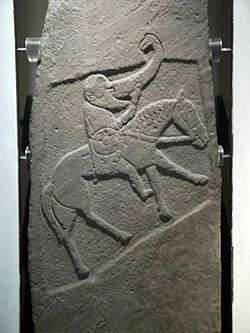

The cap is decorated in repoussé with vegetal motifs, trumpet-spirals and bird heads, while the horns have "boldly asymmetric" engraved decoration including a human face and the single complete one terminates in a modelled bird head; it has been suggested that this represents specifically the head of a northern shoveller duck.[7] This probably originally had coral eyes; the other horn lacks its tip.[8] The cap has holes for the ears of the pony;[9] the angle at which the cap is currently displayed, as in the photo here, is designed to show the decoration clearly, and corresponds to that the cap would have had with the horse bowing its head. The photos on the museum website show the normal angle when worn better, with the edges on the sides roughly parallel with the ground.[10]

The engraved decoration on the horns is described by Lloyd Laing as "very neatly incised and very elaborate; each pattern begins with a circular yin-yang element and swells outwards into a central design before tailing off into a delicate fan-shaped tip. A tiny full-face human mask has been incorporated into the central element of the larger horn."[11] The pony-cap is 10.5 inches long, and the complete horn 16.5 inches along its curve,[12] the dimensions meaning that the horse wearing the cap "would have had to be a very small one".[13] The cap has a large piece at its back proper left missing, and three ancient repairs, using small plates, each decorated with patterns; in the photograph here one can be seen between the ear hole and the near horn, another vertical near the front edge of the cap.[14]

Artistic context

The horns and cap are part of a small group of elaborately decorated objects that are the main evidence for one of the last phases of "Insular" La Tène style in Britain and Ireland, known as "Style IV" in an extension of the scheme originally devised by de Navarro for Continental works. Other objects include the Battersea and Witham Shields, and an especially closely related work is a bronze shield boss found in the river Thames at Wandsworth in London, to the extent that Piggot designates a "Torrs-Wandsworth style"; all these three objects are in the British Museum. The group includes other objects from Britain and Ireland.[15]

In a Scottish context, the cap has been seen as a leading example of a distinctive "Galloway style" of La Tène art, closely related to developments in northern Ireland, a short distance across the Irish Sea.[16] Other scholars see the pieces as imported products, perhaps from "east-central England".[17][18]

Function

The pony-cap is normally regarded as a Celtic example of a champron or chamfrein, a piece of horse armour of the type familiar from the late Middle Ages, but has also been seen as intended to be worn by a human in ritual contexts.[20] This was also the view of local antiquaries when the object was found; in its first publication in 1841 it was described as "a mummer's head-mask", though thought to be medieval.[21] It would have been held on by leather straps, with a plume rising from the top of the cap.[22] No other metal champron from ancient times is known, but there appear to be Celtic and classical Greek examples in materials such as boiled leather, including one from Newstead Fort, a Roman outpost in Scotland.[23] Another possibility is that the intended wearer was a wooden cult statue of a horse, which would help explain the small size.[13]

The theory that the horns were drinking-horn mounts, never joined to the cap in ancient times, was first proposed by Professors Piggott and Atkinson in 1955, and was widely accepted for about three decades, leading to the horns being detached from the cap and displayed separately. The single surviving bird's head terminal is comparable to much later early medieval examples from Anglo-Saxon burials (for example from Sutton Hoo and the Taplow burial) as well as Irish and Pictish contexts, which are either known or assumed to have decorated the tips of drinking-horns.[24] However the theory depended on the assumption that the holes and rivets used to attach the horns to the cap were all the work of a 19th-century restorer. Subsequent investigation suggested that this was not in fact the case, and "opinion has swung back" to support the original reconstruction,[13] and by the late 1960s Piggott and Atkinson preferred "to think of the horns as yoke-terminals" for chariots.[25] The possibility remains that the horns were made for a different function, but later attached to the cap at some time before its deposit.

Though no actual comparable finds have been made, some parallels have been suggested in representations of similar caps, including a figure of the mythical horse Pegasus on a coin of Tasciovanus, the largely Romanized chief who ruled the Catuvellauni from Verlamion (St Albans) between about 20 BC and 9 AD, and was the father of Cymbeline. The Pegasus appears to wear a cap from which rise two knobbed horns.[26] The remains of horses found in the graves of the Iron Age Pazyryk culture in Siberia were fitted with masks in the shape of stag heads, complete with antlers (another example) or horns (another example). In July 2015, an Iron Age burial of carefully arranged animal bones that included a horse's skull with a cow's horn on its forehead was unearthed in Dorset, England.[27]

Notes

- ↑ Laings, 102; Horns of bronze, Museum of Scotland database, accessed 27 June 2011; Sandars, 260–261; Hennig (1995), 18 ("famous and controversial")

- ↑ Laings, 101–104; Sandars, 258–268

- ↑ quotes respectively from Smith, 334 and the RCAHMS website (with map and bibliography but otherwise outdated, sticking to Piggot and Atkinson)

- ↑ Laings, 102; Horns of bronze, Museum of Scotland database, accessed 27 June 2011; Smith, 334

- ↑ See Sandars, Plate 286

- ↑ Laing, 31. Apparently they were so displayed around 1979

- ↑ Sandars, 260–263 (quoted); Laing, 70; also Pigott and Atkinson in Further reading.

- ↑ Museum of Scotland, Horns page

- ↑ Laings, 102

- ↑ Pony cap of bronze and from the other side, Museum of Scotland database, accessed 27 June 2011

- ↑ Laing, 70; Sandars, 263, fig. 100 has drawings of the engravings on both horns.

- ↑ Smith, 337, who measures many other dimensions

- 1 2 3 Henig (1995), 18

- ↑ Sandars, 261, fig. 99, which shows the whole cap as a flat projection; see also cap from the other side, Museum of Scotland database, accessed 27 June 2011.

- ↑ Laings, 100–107; Sandars, 260–268 (using a different classification scheme for the styles).

- ↑ Kilbride-Jones, 73–76

- ↑ James Neil Graham Ritchie; Anna Ritchie (5 December 1991). Scotland, archaeology and early history. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 119–. ISBN 978-0-7486-0291-9. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- ↑ Dennis William Harding (2004). The Iron Age in northern Britain: Celts and Romans, natives and invaders. Routledge. pp. 82–. ISBN 978-0-415-30149-7. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- ↑ In relation to the horns, "a reminder of Celtic conservatism" according to Laing, 71

- ↑ Green, 135, citing the recent authority of Prof. Martin Jope's article (see Further reading). Archaeologists tend to use the archaic synonym "chamfrein", following the ancient tradition of their tribe since Smith.

- ↑ Smith, 334–335

- ↑ Pony cap of bronze, Museum of Scotland database, accessed 27 June 2011 (with a better view of the engraving)

- ↑ Henig (1974), 374, citing Piggott and Atkinson, 234–235

- ↑ See Youngs, p.62, catalogue numbers 53 and 54 for Irish examples; Laing, 71

- ↑ Henig (1974), 374; see also the Museum of Scotland web site. The objection that the horns were an "incongruous" shape for terminals to the conventional cow or ox-horn led to the suggestion that aurochs horns were involved, Laing, 70

- ↑ Henig (1974), 374

- ↑ http://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/archaeology/news/the-boneyard-of-the-bizarre-that-rewrites-our-celtic-past-to-include-hybridanimal-monster-myths-10381965.html

References

- Green, Miranda. Animals in Celtic Life and Myth, 1998, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-18588-2, ISBN 978-0-415-18588-2

- Henig, Martin (1974). "A Coin of Tasciovanus", Britannia, Vol. 5, 1974, 374–375, JSTOR

- Henig, Martin (1995). The Art of Roman Britain, Routledge, 1995, ISBN 0-415-15136-8, ISBN 978-0-415-15136-8

- Kilbride-Jones, H. E., Celtic craftsmanship in bronze, 1980, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-7099-0387-1, ISBN 978-0-7099-0387-1

- "Laings", Lloyd Laing and Jennifer Laing. Art of the Celts: From 700 BC to the Celtic Revival, 1992, Thames & Hudson (World of Art), ISBN 0-500-20256-7

- Laing, Lloyd Robert. Celtic Britain, 1979, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-7100-0131-2, ISBN 978-0-7100-0131-3

- Sandars, Nancy K., Prehistoric Art in Europe, Penguin (Pelican, now Yale, History of Art), 1968 (nb 1st edn.)

- Smith, John Alexander, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Volume 7, December 1867, 334–341, Printed for the Society by Neill and Company, 1870, google books

- Youngs, Susan (ed), "The Work of Angels", Masterpieces of Celtic Metalwork, 6th–9th centuries AD, 1989, British Museum Press, London, ISBN 0714105546

Further reading

- Calder, Jenni. The Wealth of a Nation, Edinburgh: National Museums of Scotland and Glasgow: Richard Drew Publishing, 1989, pp. 97–9.

- Jope, E. M., "Torrs, Aylesford, and the Padstow hobby-horse", in From the Stone Age to the 'Forty-Five', studies presented to RBK Stevenson, ed. A. O'Connor and DV Clarke, 1983, 149–59, John Donald, Edinburgh – interprets Torrs as part of a mummer's costume. See also p. 130 in the same volume.

- MacGregor, Morna. Early Celtic art in North Britain. Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1976, vol. 1, pp. 23–4; vol. 2, no. 1.

- Megaw, J. V. S., Art of the European Iron Age: a study of the elusive image, Adams & Dart, 1970

- Piggott S. and Atkinson R., "The Torrs Chamfrein", 'Archaeologia, XCVI, 197–235, 1955 – the paper proposing the "drinking-horn mounts" theory.