Tošo Dabac

| Tošo Dabac | |

|---|---|

Tošo Dabac in 1951 | |

| Born |

Teodor Eugen Marija Dabac 18 May 1907 Nova Rača, Austria-Hungary |

| Died |

9 May 1970 (aged 62) Zagreb, SFR Yugoslavia |

| Nationality | Yugoslav / Croatian |

| Known for | Photography |

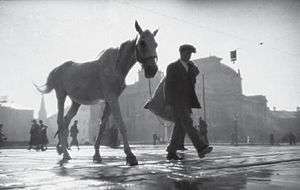

Tošo Dabac (pronounced [toʃo dabats]; 18 May 1907 – 9 May 1970) was a Croatian photographer of international renown.[1][2][3] Although his work was often exhibited and prized abroad, Dabac spent nearly his entire working career in Zagreb.[1] While he worked on many different kinds of publications throughout his career, he is primarily notable for his black-and-white photographs of Zagreb street life during the Great Depression era.[4]

Life and career

Early life

Dabac was born in the small town of Nova Rača near the city of Bjelovar in central Croatia. After finishing primary school in his home town, his family moved to Samobor. He enrolled at the Royal Classical Gymnasium (Kraljevska klasična gimnazija) in Zagreb, and upon graduation, at the University of Zagreb Faculty of Law. In the late 1920s, Dabac worked for the Austrian film distribution company Fanamet-Film. After it closed down, he was employed by the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer subsidiary in Zagreb, where he worked as a translator and as their press officer for Southeast Europe between 1928 and 1937.[2][4][5][6] After he dropped out of law school in 1927, he became the editor of Metro Megafon magazine.[1]

Dabac's earliest surviving photograph is a panorama of Samobor, taken on 7 March 1925.[3] His work was first shown publicly at an amateur exhibition held in the small town of Ivanec in 1932. The pioneering gallery hosting this exhibition later contributed to the development of photography in the country by publishing Croatian-language editions of the European art photography magazine Die Galerie in 1933 and 1934.[4] In 1932 Dabac began working as a professional photojournalist in collaboration with Đuro Janeković.

Rise to prominence

A year after his first exhibition, Dabac's works were selected for exhibition at the Second International Photography Salon in Prague in 1933 along with works by František Drtikol and László Moholy-Nagy. In the same year, his photographs were put on display in the Second Philadelphia International Salon of Photography held at the Philadelphia Museum of Art along with works by Margaret Bourke-White, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paul Outerbridge, Ilse Bing and others, in an exhibition curated by art historian Beaumont Newhall.[4]

Later, Dabac worked as a correspondent for various foreign news agencies. From 1933 and 1937, he created a series of photographs first exhibited under the title Misery (Croatian: Bijeda) but later renamed Street People (Croatian: Ljudi s ulice). This series earned him a reputation as an artful chronicler of Zagreb street life.[1]

In 1937 Dabac opened a photograph studio and married Julija Grill, an operetta singer. That year, his street photographs were selected for the Fourth International Salon held at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, where his photograph Road to the Guillotine (Croatian: Put na giljotinu) claimed an award. Later that year, his work was shown at group exhibitions held at the San Francisco Museum of Art (along with works by Edward Steichen, Brassaï, Man Ray, Alexander Rodchenko and Ansel Adams) and at the Boston Camera Club, where another of his photographs, the Philosopher of Life (Croatian: Filozof života) was awarded a prize. In 1938 he won two monthly contests organised by the American photography magazine Camera Craft.

In 1940 Tošo Dabac moved his studio to 17 Ilica street. Not only would the studio remain his workplace for the rest of his life, but it also soon became an important meeting place where many prominent intellectuals and artists in Zagreb gathered.[1] That year, a photograph of his appeared on the cover of an issue of the German photography magazine Photographische Rundschau which featured a series of Dabac's photographs of Croatia.

After World War II, Dabac joined the Croatian Association of Visual Artists (Croatian: Udruženje likovnih umjetnika Hrvatske or ULUH). In 1945, he spent a month shooting photographs around Istria while writing a diary which depicts the post-war state of the region. In 1946 he continued to shoot natural wonders and cultural heritage sites along the Dalmatian coast from Istria to Dubrovnik.

In the following years Dabac regularly contributed to Jugoslavija magazine and made a series of photographs of medieval sculptures and frescos, tourist sites and Dubrovnik summer houses. He was also hired to work as a photographer at many exhibitions and trade fairs where Yugoslav companies participated (in Toronto in 1949, in Chicago in 1950, in Moscow in 1958 and at the 1958 Expo in Brussels). In 1952, his works were shown at an international exhibition in Lucerne, along with others such as Richard Avedon, Cecil Beaton, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank and André Kertész.

Later life

In 1960, Dabac exhibited at an international exhibition that has since gained cult status, Das menschliche Antlitz Europas, along with Robert Capa, Werner Bischof, Edward Steichen and others. In 1965, his work was shown at Karl Pawek's exhibition titled Was ist der Mensch?. In 1966, he was awarded the Vladimir Nazor Award, given by the Croatian Ministry of Culture for highest achievements in visual arts,[7] for his photographs of the stećak tombstones. Later that year, he won the annual award and the life achievement diploma by the Yugoslav Photographic Union (Fotosavez Jugoslavije).

Dabac worked for many international publishing houses, including Thames & Hudson, Encyclopædia Britannica, Alber Müller Verlag of Zürich, Hanns Reich Verlag of Munich, and others. His photographs were used in both local and foreign encyclopedias. He also wrote and collaborated on many books of photographs of cities and regions throughout Croatia and Yugoslavia. Dabac was a member of several national and international photographic organisations; from 1953 he was a member of the Photographic Society of America and he was made an honorary member of the Royal Photographic Society of Belgium (CREPSA), the Dutch salon FOKUS, and the holder of titles Hon. exc. by FIAP and MS (Master of Photography) by the Yugoslav Photographic Union.

Legacy

Tošo Dabac died on 9 May 1970 in Zagreb and was buried at Mirogoj Cemetery.[8]

In 1975, the Zagreb Photographic Club (Croatian: Fotoklub Zagreb) established an annual award given to Croatian photographers for highest achievements in the field.[9]

Dabac's entire photographic opus of nearly 200,000 negatives is kept in the Tošo Dabac Archive, at his former studio. In March 2006, the archive was acquired by the City of Zagreb and is now managed by the Museum of Contemporary Art.[10]

Selected exhibitions

Group

- 1933 – "Second Philadelphia International Salon of Photography", Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, USA

- 1937 – "Fourth International Salon"", American Museum of Natural History, New York, USA

- 1937 – "Invitational Salon of International Photography", San Francisco Museum of Art, San Francisco, USA

- 1937 – "Sixth International Salon", Boston Camera Club, Boston, USA

- 1939 – "Sixth International Salon of Photography, Centennial Exhibition ", American Museum of Natural History, New York, USA

- 1951 – "Mostra della Fotografia Europea", Palazzo di Brera, Milan, Italy

- 1952 – "Welt Ausstellung der Photographie", Lucerne, Switzerland

- 1960 – "International Salon of Photography Das menschliche Antlitz Europas", Munich, West Germany

- 1965 – "Welt Ausstellung der Photographie, Was ist der Mensch?", Hamburg, West Germany

- 1968 – "Tombstones of medieval Bosnia", National Gallery in Prague, Belvedere Palace, Prague, Czechoslovakia

Solo

- 1962 – "Salon of Photography", Belgrade, Yugoslavia

- 1968 – "Tošo Dabac Retrospective", Museum of Arts and Crafts, Zagreb, Yugoslavia

- 1969 – "The Art of the Stećak", Art Pavilion, Zagreb, Yugoslavia

- 1969 – "The Days of Yugoslavia", Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany

- 1969 – Split Art Gallery, Split, Yugoslavia

- 1972 – "Tošo Dabac und sein Atelier", Kunstverein Mannheim (Mannheim Society of Art), Mannheim, West Germany

- 1975 – "Mostra fotografica ad invito: I grandi autori FIAP", Padua, Italy

- 1984 – "Fotografie di Tošo Dabac", Centro San Fedele, Milan, Italy

- 1988 – "Color photographs by Tošo Dabac 1940–1941", Studio Fotocolor, Zagreb, Yugoslavia

- 1992 – "Mois de la Photo Mitteleuropa Tošo Dabac: une oeuvre de transition", Grande halle de la Villette, Paris, France

- 1994 – "1930s Zagreb", Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb, Croatia

- 2002 – "The Photographer Tošo Dabac", Klovićevi dvori Gallery, Zagreb, Croatia

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kostelnik, Branko (24 November 2007). "Sve Tošine žene" [All Tošo's women] (in Croatian). Jutarnji list. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- 1 2 "Tošo Dabac, Life & Photographs, 1907–1970". Culturenet.hr. 9 January 2009. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- 1 2 "Tošo Dabac - Biografija" (in Croatian). The Badrov Gallery. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 "Biografija" (in Croatian). Blur Magazine. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ↑ Bajlo, Ivan. "Tošo Dabac (1907. - 1970.)" (in Croatian). Svijet-Fotografije.com. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ↑ "Dubrovnik Culture and Event - Tošo Dabac: Scenes from the street". In Your Pocket City Guides. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ↑ "Dobitnici "Nagrade Vladimir Nazor" 1959–2005" [Vladimir Nazor Prize winners 1959–2005] (DOC) (in Croatian). Croatian Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ↑ "List of notable people buried at Mirogoj". Mirogoj Cemetery. Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- ↑ Pavleković, Nikolina (29 April 2009). "Hoyka i Atletić primili Nagradu Tošo Dabac" [Hoyka and Atletić receive the Tošo Dabac Award] (in Croatian). Javno.hr. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ↑ "The Tošo Dabac Archive". msu.hr. Museum of Contemporary Art Zagreb. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

External links

- Biography at Culturenet.hr

- Website dedicated to Tošo Dabac made by Blur Magazine, a Croatian photographic monthly magazine (Croatian)

- Gallery of photographs by Dabac at Fotografija.hr (Croatian)

- Gospon fotograf, Zagreb vas ima rad! (Croatian)

|