Time travel

Time travel is the concept of movement (often by a human) between different points in time in a manner analogous to moving between different points in space, typically using a hypothetical device known as a time machine. Time travel is a recognized concept in philosophy and fiction, but travel to an arbitrary point in time has a very limited support in theoretical physics, usually only in conjunction with quantum mechanics or Einstein–Rosen bridges. Sometimes the above narrow meaning of time travel is used, sometimes a broader meaning. For example, travel into the future (not the past) via time dilation is a well-proven phenomenon in physics (relativity) and is routinely experienced by astronauts, but only by several milliseconds, as they can verify by checking a precise watch against a clock that remained on Earth. Time dilation by years into the future could be done by taking a round trip during which motion occurs at speeds comparable to the speed of light, but this is not currently technologically feasible for vehicles.[1]

The concept is popular in science fiction novels; a science fiction novel written in 1895 called The Time Machine, by H. G. Wells, was instrumental in moving the concept of time travel to the forefront of the public imagination, but the earlier short story "The Clock That Went Backward", by Edward Page Mitchell, involves a clock that, by means unspecified, allows three men to travel backward in time.[2][3] Non-technological forms of time travel had appeared in a number of earlier stories such as Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol. More recently, with advancing technology and a greater scientific understanding of the universe, the plausibility of time travel has been explored in greater detail by science fiction writers, philosophers, and physicists.

History of the time travel concept

Forward time travel

There is no widespread agreement as to which written work should be recognized as the earliest example of a time travel story, since a number of early works feature elements ambiguously suggestive of time travel. Ancient folk tales and myths sometimes involved something akin to traveling forward in time; for example, in Hindu mythology, the Mahabharata mentions the story of the King Raivata Kakudmi, who travels to heaven to meet the creator Brahma and is shocked to learn that many ages have passed when he returns to Earth.[4][5]

The Buddhist Pāli Canon also mentions time moving at different paces, and in the Payasi Sutta, one of the Buddha's chief disciples, Kumara Kassapa, explains to the skeptic Payasi that "In the Heaven of the Thirty Three Devas, time passes at a different pace, and people live much longer. "In the period of our century; one hundred years, only a single day; twenty four hours would have passed for them."[6]

Another of the earliest known stories to involve traveling forward in time to a distant future was the Japanese tale of "Urashima Tarō",[7] first described in the Nihongi (720).[8] It was about a young fisherman named Urashima Taro who visits an undersea palace and stays there for three days. After returning home to his village, he finds himself 300 years in the future, when he is long forgotten, his house in ruins, and his family long dead. Another very old example of this type of story can be found in the Talmud with the story of Honi HaM'agel who went to sleep for 70 years and woke up to a world where his grandchildren were grandparents and where all his friends and family were dead.[9]

A more recent story involving travel to the future is Louis-Sébastien Mercier's L'An 2440, rêve s'il en fût jamais ("The Year 2440: A Dream If Ever There Were One"), a utopian novel in which the main character is transported to the year 2440. An extremely popular work (it went through 25 editions after its first appearance in 1771), it describes the adventures of an unnamed man who, after engaging in a heated discussion with a philosopher friend about the injustices of Paris, falls asleep and finds himself in a Paris of the future. Robert Darnton writes that "despite its self-proclaimed character of fantasy...L'An 2440 demanded to be read as a serious guidebook to the future."[10]

More recently, Washington Irving's 1819 story "Rip Van Winkle" tells of a man named Rip Van Winkle who takes a nap on a mountain and wakes up 20 years in the future, when he has been forgotten, his wife dead, and his daughter grown up.[7] Sleep was also used for time travel in H.G. Wells' The Sleeper Awakes, about a man who wakes 200 years in the future after falling into a state of sleep resembling hibernation or suspended animation.

Backward time travel

Backward time travel seems to be a more modern idea, but its origin is also somewhat ambiguous. One early story with hints of backward time travel is Memoirs of the Twentieth Century (1733) by Samuel Madden, which is mainly a series of letters from British ambassadors in various countries to the British Lord High Treasurer, along with a few replies from the British Foreign Office, all purportedly written in 1997 and 1998 and describing the conditions of that era.[11] However, the framing story is that these letters were actual documents given to the narrator by his guardian angel one night in 1728; for this reason, Paul Alkon suggests in his book Origins of Futuristic Fiction that "the first time-traveler in English literature is a guardian angel who returns with state documents from 1998 to the year 1728",[12] although the book does not explicitly show how the angel obtained these documents. Alkon later qualifies this by writing, "It would be stretching our generosity to praise Madden for being the first to show a traveler arriving from the future", but also says that Madden "deserves recognition as the first to toy with the rich idea of time-travel in the form of an artifact sent backward from the future to be discovered in the present."[11]

In 1836 Alexander Veltman published Predki Kalimerosa: Aleksandr Filippovich Makedonskii (The Forebears of Kalimeros: Alexander, son of Philip of Macedon), which has been called the first original Russian science fiction novel and the first novel to use time travel.[13] In it, the narrator rides to ancient Greece on a hippogriff, meets Aristotle, and goes on a voyage with Alexander the Great before returning to the 19th century.

In the science fiction anthology Far Boundaries (1951), the editor August Derleth identifies the short story "Missing One's Coach: An Anachronism", written for the Dublin Literary Magazine[14] by an anonymous author in 1838, as a very early time travel story.[15] In this story, the narrator is waiting under a tree to be picked up by a coach which will take him out of Newcastle, when he suddenly finds himself transported back over a thousand years. He encounters the Venerable Bede in a monastery, and gives him somewhat ironic explanations of the developments of the coming centuries. However, the story never makes it clear whether these events actually occurred or were merely a dream: the narrator says that when he initially found a comfortable-looking spot in the roots of the tree, he sat down, "and as my sceptical reader will tell me, nodded and slept", but then says that he is "resolved not to admit" this explanation. A number of dreamlike elements of the story may suggest otherwise to the reader, such as the fact that none of the members of the monastery seem to be able to see him at first, and the abrupt ending in which Bede has been delayed talking to the narrator and so the other monks burst in thinking that some harm has come to him and suddenly the narrator finds himself back under the tree in the present (August 1837), with his coach having just passed his spot on the road leaving him stranded in Newcastle for another night.[16]

Charles Dickens' 1843 book A Christmas Carol is considered by some[17] to be one of the first depictions of time travel in both directions, as the main character, Ebenezer Scrooge, is transported to Christmases past, present and yet to come. However, these might be considered mere visions rather than actual time travel, since Scrooge only viewed each time-period passively, unable to interact with them.

A clearer example of backward time travel is found in the popular 1861 book Paris avant les hommes (Paris before Men) by the French botanist and geologist Pierre Boitard, published posthumously. In this story, the main character is transported into the prehistoric past by the magic of a "lame demon" (a French pun on Boitard's name), where he encounters such extinct animals as a Plesiosaur, as well as Boitard's imagined version of an apelike human ancestor, and is able to actively interact with some of them.[18]

In 1881, Edward Everett Hale published "Hands Off", about an unnamed being (possibly the soul of a person who had recently died) free to travel through time and space, who interferes with Earth history in Ancient Egypt, preventing Joseph from being sold into slavery. This was the first known story to feature an alternate history being created as a result of time travel.[19]

The first time travel story to feature time travel by means of a machine of some kind was the short story "The Clock that Went Backward" by Edward Page Mitchell,[20] which appeared in the New York Sun in 1881. However, the mechanism is borderline fantasy in this case—a clock that, when wound, begins to run backward and transports people in the vicinity backward in time, with no explanation as to where the clock came from or how it gained this ability.[21]

Enrique Gaspar y Rimbau's 1887 book El Anacronópete[22] was the first story to feature a vessel that had been engineered by an inventor to transport its riders through time.[23] Andrew Sawyer has commented that the story "does seem to be the first literary description of a time machine noted so far", adding that "Edward Page Mitchell's story The Clock That Went Backward (1881) is usually described as the first time-machine story, but I'm not sure that a clock quite counts."[24]

In 1889 Svatopluk Čech published the novel Nový epochální výlet pana Broučka, tentokráte do XV. století ("The Epoch-making Excursion of Mr. Brouček, this time to the 15th Century").

Mark Twain's A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (1889), in which the protagonist finds himself in the time of King Arthur after a fight in which he is hit with a sledgehammer, was another early time travel story which helped bring the concept to a wide audience, and was also one of the first stories to show history being changed by a time traveler's actions.

The notion of a vehicle designed for time travel gained popularity with the H. G. Wells story The Time Machine, published in 1895 (preceded by a less influential story of time travel which Wells wrote in 1888, titled "The Chronic Argonauts"). The term "time machine", coined by Wells, is now universally used to refer to such a vehicle.

Since that time, both science and fiction (see Time travel in fiction) have expanded on the concept of time travel.

Theory

Some theories, most notably special and general relativity, suggest that suitable geometries of spacetime or specific types of motion in space might allow time travel into the past and future if these geometries or motions were possible.[25] In technical papers, physicists generally avoid the commonplace language of "moving" or "traveling" through time ("movement" normally refers only to a change in spatial position as the time coordinate is varied), and instead discuss the possibility of closed timelike curves, which are worldlines that form closed loops in spacetime, allowing objects to return to their own past. There are known to be solutions to the equations of general relativity that describe spacetimes which contain closed timelike curves (such as Gödel spacetime), but the physical plausibility of these solutions is uncertain.

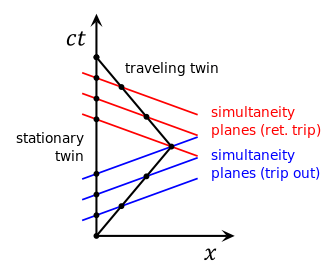

Relativity predicts that if one were to move away from the Earth at relativistic velocities and return, more time would have passed on Earth than for the traveler, so in this sense it is accepted that relativity allows "travel into the future" (according to relativity there is no single objective answer to how much time has really passed between the departure and the return, but there is an objective answer to how much proper time has been experienced by both the Earth and the traveler, i.e., how much each has aged; see twin paradox). On the other hand, many in the scientific community believe that backward time travel is highly unlikely. Any theory that would allow time travel would introduce potential problems of causality. The classic example of a problem involving causality is the "grandfather paradox": what if one were to go back in time and kill one's own grandfather before one's father was conceived? But some scientists believe that paradoxes can be avoided, by appealing either to the Novikov self-consistency principle or to the notion of branching parallel universes.

Tourism in time

Stephen Hawking has suggested that the absence of tourists from the future is an argument against the existence of time travel: this is a variant of the Fermi paradox. Of course, this would not prove that time travel is physically impossible, since it might be that time travel is physically possible but that it is never developed (or is cautiously never used); and even if it were developed, Hawking notes elsewhere that time travel might only be possible in a region of spacetime that is warped in the correct way, and that if we cannot create such a region until the future, then time travelers would not be able to travel back before that date, so "[t]his picture would explain why" the world hasn't already been overrun by "tourists from the future."[26] This simply means that, until a time machine were actually to be invented, we would not be able to see time travelers. Carl Sagan also once suggested the possibility that time travelers could be here, but are disguising their existence or are not recognized as time travelers, because bringing unintentional changes to the time-space continuum might bring about undesired outcomes to those travelers. It might also alter established past events.[27] There is also the possibility that if events were changed, we would never notice it because all events following and our memories would have been instantly altered to remain congruent with the newly established timeline.

General relativity

However, the theory of general relativity does suggest a scientific basis for the possibility of backward time travel in certain unusual scenarios, although arguments from semiclassical gravity suggest that when quantum effects are incorporated into general relativity, these loopholes may be closed.[28] These semiclassical arguments led Hawking to formulate the chronology protection conjecture, suggesting that the fundamental laws of nature prevent time travel,[29] but physicists cannot come to a definite judgment on the issue without a theory of quantum gravity to join quantum mechanics and general relativity into a completely unified theory.[30]:150

Time travel to the past in physics

Time travel to the past is theoretically allowed using the following methods:[31]

- Traveling faster than the speed of light

- The use of cosmic strings and black holes

- Wormholes and Alcubierre drive

Via faster-than-light (FTL) travel

If one were able to move information or matter from one point to another faster than light, then according to the theory of relativity, there would be some inertial frame of reference in which the signal or object was moving backward in time. This is a consequence of the relativity of simultaneity in special relativity, which says that in some cases different reference frames will disagree on whether two events at different locations happened "at the same time" or not, and they can also disagree on the order of the two events. Technically, these disagreements occur when the spacetime interval between the events is 'space-like', meaning that neither event lies in the future light cone of the other.[32] If one of the two events represents the sending of a signal from one location and the second event represents the reception of the same signal at another location, then as long as the signal is moving at the speed of light or slower, the mathematics of simultaneity ensures that all reference frames agree that the transmission-event happened before the reception-event.[32]

However, in the case of a hypothetical signal moving faster than light, there would always be some frames in which the signal was received before it was sent, so that the signal could be said to have moved backward in time. And since one of the two fundamental postulates of special relativity says that the laws of physics should work the same way in every inertial frame, then if it is possible for signals to move backward in time in any one frame, it must be possible in all frames. This means that if observer A sends a signal to observer B which moves FTL (faster than light) in A's frame but backward in time in B's frame, and then B sends a reply which moves FTL in B's frame but backward in time in A's frame, it could work out that A receives the reply before sending the original signal, a clear violation of causality in every frame. An illustration of such a scenario using spacetime diagrams can be found here.[33] The scenario is sometimes referred to as a tachyonic antitelephone.

According to special relativity, it would take an infinite amount of energy to accelerate a slower-than-light object to the speed of light. Although relativity does not forbid the theoretical possibility of tachyons which move faster than light at all times, when analyzed using quantum field theory, it seems that it would not actually be possible to use them to transmit information faster than light.[34] There is also no widely agreed-upon evidence for the existence of tachyons; the faster-than-light neutrino anomaly had opened the possibility that neutrinos might be tachyons, but the results of the experiment were found to be invalid upon further analysis.

Special spacetime geometries

The general theory of relativity extends the special theory to cover gravity, illustrating it in terms of curvature in spacetime caused by mass-energy and the flow of momentum. General relativity describes the universe under a system of field equations, and there exist solutions to these equations that permit what are called "closed time-like curves", and hence time travel into the past.[25] The first of these was proposed by Kurt Gödel, a solution known as the Gödel metric, but his (and many others') example requires the universe to have physical characteristics that it does not appear to have.[25] Whether general relativity forbids closed time-like curves for all realistic conditions is unknown.

Using wormholes

Wormholes are a hypothetical warped spacetime which are also permitted by the Einstein field equations of general relativity,[35] although it would not be possible to travel through a wormhole unless it were what is known as a traversable wormhole.

A proposed time-travel machine using a traversable wormhole would (hypothetically) work in the following way: One end of the wormhole is accelerated to some significant fraction of the speed of light, perhaps with some advanced propulsion system, and then brought back to the point of origin. Alternatively, another way is to take one entrance of the wormhole and move it to within the gravitational field of an object that has higher gravity than the other entrance, and then return it to a position near the other entrance. For both of these methods, time dilation causes the end of the wormhole that has been moved to have aged less than the stationary end, as seen by an external observer; however, time connects differently through the wormhole than outside it, so that synchronized clocks at either end of the wormhole will always remain synchronized as seen by an observer passing through the wormhole, no matter how the two ends move around.[36] This means that an observer entering the accelerated end would exit the stationary end when the stationary end was the same age that the accelerated end had been at the moment before entry; for example, if prior to entering the wormhole the observer noted that a clock at the accelerated end read a date of 2007 while a clock at the stationary end read 2012, then the observer would exit the stationary end when its clock also read 2007, a trip backward in time as seen by other observers outside. One significant limitation of such a time machine is that it is only possible to go as far back in time as the initial creation of the machine;[37] in essence, it is more of a path through time than it is a device that itself moves through time, and it would not allow the technology itself to be moved backward in time.

According to current theories on the nature of wormholes, construction of a traversable wormhole would require the existence of a substance with negative energy (often referred to as "exotic matter"). More technically, the wormhole spacetime requires a distribution of energy that violates various energy conditions, such as the null energy condition along with the weak, strong, and dominant energy conditions.[38] However, it is known that quantum effects can lead to small measurable violations of the null energy condition,[38] and many physicists believe that the required negative energy may actually be possible due to the Casimir effect in quantum physics.[39] Although early calculations suggested a very large amount of negative energy would be required, later calculations showed that the amount of negative energy can be made arbitrarily small.[40]

In 1993, Matt Visser argued that the two mouths of a wormhole with such an induced clock difference could not be brought together without inducing quantum field and gravitational effects that would either make the wormhole collapse or the two mouths repel each other.[41] Because of this, the two mouths could not be brought close enough for causality violation to take place. However, in a 1997 paper, Visser hypothesized that a complex "Roman ring" (named after Tom Roman) configuration of an N number of wormholes arranged in a symmetric polygon could still act as a time machine, although he concludes that this is more likely a flaw in classical quantum gravity theory rather than proof that causality violation is possible.[42]

Other approaches based on general relativity

Another approach involves a dense spinning cylinder usually referred to as a Tipler cylinder, a GR solution discovered by Willem Jacob van Stockum[43] in 1936 and Kornel Lanczos[44] in 1924, but not recognized as allowing closed timelike curves[45] until an analysis by Frank Tipler[46] in 1974. If a cylinder is infinitely long and spins fast enough about its long axis, then a spaceship flying around the cylinder on a spiral path could travel back in time (or forward, depending on the direction of its spiral). However, the density and speed required is so great that ordinary matter is not strong enough to construct it. A similar device might be built from a cosmic string, but none are known to exist, and it does not seem to be possible to create a new cosmic string.

Physicist Robert Forward noted that a naïve application of general relativity to quantum mechanics suggests another way to build a time machine. A heavy atomic nucleus in a strong magnetic field would elongate into a cylinder, whose density and "spin" are enough to build a time machine. Gamma rays projected at it might allow information (not matter) to be sent back in time; however, he pointed out that until we have a single theory combining relativity and quantum mechanics, we will have no idea whether such speculations are nonsense.

A more fundamental objection to time travel schemes based on rotating cylinders or cosmic strings has been put forward by Stephen Hawking, who proved a theorem showing that according to general relativity it is impossible to build a time machine of a special type (a "time machine with the compactly generated Cauchy horizon") in a region where the weak energy condition is satisfied, meaning that the region contains no matter with negative energy density (exotic matter). Solutions such as Tipler's assume cylinders of infinite length, which are easier to analyze mathematically, and although Tipler suggested that a finite cylinder might produce closed timelike curves if the rotation rate were fast enough,[47] he did not prove this. But Hawking points out that because of his theorem, "it can't be done with positive energy density everywhere! I can prove that to build a finite time machine, you need negative energy."[30]:96 This result comes from Hawking's 1992 paper on the chronology protection conjecture, where he examines "the case that the causality violations appear in a finite region of spacetime without curvature singularities" and proves that "[t]here will be a Cauchy horizon that is compactly generated and that in general contains one or more closed null geodesics which will be incomplete. One can define geometrical quantities that measure the Lorentz boost and area increase on going round these closed null geodesics. If the causality violation developed from a noncompact initial surface, the averaged weak energy condition must be violated on the Cauchy horizon."[48] However, this theorem does not rule out the possibility of time travel 1) by means of time machines with the non-compactly generated Cauchy horizons (such as the Deutsch-Politzer time machine) and 2) in regions which contain exotic matter (which would be necessary for traversable wormholes or the Alcubierre drive). Because the theorem is based on general relativity, it is also conceivable a future theory of quantum gravity which replaced general relativity would allow time travel even without exotic matter (though it is also possible such a theory would place even more restrictions on time travel, or rule it out completely as postulated by Hawking's chronology protection conjecture).

Experiments carried out

Certain experiments carried out give the impression of reversed causality but are subject to interpretation. For example, in the delayed choice quantum eraser experiment performed by Marlan Scully, pairs of entangled photons are divided into "signal photons" and "idler photons", with the signal photons emerging from one of two locations and their position later measured as in the double-slit experiment, and depending on how the idler photon is measured, the experimenter can either learn which of the two locations the signal photon emerged from or "erase" that information. Even though the signal photons can be measured before the choice has been made about the idler photons, the choice seems to retroactively determine whether or not an interference pattern is observed when one correlates measurements of idler photons to the corresponding signal photons. However, since interference can only be observed after the idler photons are measured and they are correlated with the signal photons, there is no way for experimenters to tell what choice will be made in advance just by looking at the signal photons, and under most interpretations of quantum mechanics the results can be explained in a way that does not violate causality.

The experiment of Lijun Wang might also show causality violation since it made it possible to send packages of waves through a bulb of caesium gas in such a way that the package appeared to exit the bulb 62 nanoseconds before its entry. But a wave package is not a single well-defined object but rather a sum of multiple waves of different frequencies (see Fourier analysis), and the package can appear to move faster than light or even backward in time even if none of the pure waves in the sum do so. This effect cannot be used to send any matter, energy, or information faster than light,[49] so this experiment is understood not to violate causality either.

The physicists Günter Nimtz and Alfons Stahlhofen, of the University of Koblenz, claim to have violated Einstein's theory of relativity by transmitting photons faster than the speed of light. They say they have conducted an experiment in which microwave photons traveled "instantaneously" between a pair of prisms that had been moved up to 3 ft (0.91 m) apart, using a phenomenon known as quantum tunneling. Nimtz told New Scientist magazine: "For the time being, this is the only violation of special relativity that I know of." However, other physicists say that this phenomenon does not allow information to be transmitted faster than light. Aephraim Steinberg, a quantum optics expert at the University of Toronto, Canada, uses the analogy of a train traveling from Chicago to New York, but dropping off train cars at each station along the way, so that the center of the train moves forward at each stop; in this way, the speed of the center of the train exceeds the speed of any of the individual cars.[50]

Some physicists have performed experiments that attempted to show causality violations, but so far without success. The "Space-time Twisting by Light" (STL) experiment run by physicist Ronald Mallett attempts to observe a violation of causality when a neutron is passed through a circle made up of a laser whose path has been twisted by passing it through a photonic crystal. Mallett has some physical arguments that suggest that closed timelike curves would become possible through the center of a laser that has been twisted into a loop. However, other physicists dispute his arguments (see objections).

Shengwang Du claims in a peer-reviewed journal to have observed single photons' precursors, saying that they travel no faster than c in a vacuum. His experiment involved slow light as well as passing light through a vacuum. He generated two single photons, passing one through rubidium atoms that had been cooled with a laser (thus slowing the light) and passing one through a vacuum. Both times, apparently, the precursors preceded the photons' main bodies, and the precursor traveled at c in a vacuum. According to Du, this implies that there is no possibility of light traveling faster than c (and, thus, violating causality).[51] Some members of the media took this as an indication of proof that time travel to the past using superluminal speeds was impossible.[52][53]

Non-physics-based experiments

Several experiments have been carried out to try to entice future humans, who might invent time travel technology, to come back and demonstrate it to people of the present time. Events such as Perth's Destination Day (2005) or MIT's Time Traveler Convention heavily publicized permanent "advertisements" of a meeting time and place for future time travelers to meet. Back in 1982, a group in Baltimore, Maryland, identifying itself as the Krononauts, hosted an event of this type welcoming visitors from the future.[54][55][56] These experiments only stood the possibility of generating a positive result demonstrating the existence of time travel, but have failed so far—no time travelers are known to have attended either event. It is hypothetically possible that future humans have traveled back in time, but have traveled back to the meeting time and place in a parallel universe.[57]

Another factor is that for all the time travel devices considered under current physics (such as those that operate using wormholes), it is impossible to travel back to before the time machine was actually made.[58][59]

Time travel to the future in physics

There are various ways in which a person could "travel into the future" in a limited sense: the person could set things up so that in a small amount of his own subjective time, a large amount of subjective time has passed for other people on Earth. For example, an observer might take a trip away from the Earth and back at relativistic velocities, with the trip only lasting a few years according to the observer's own clocks, and return to find that thousands of years had passed on Earth. According to relativity, there would be no objective answer to the question of how much time "really" passed during the trip; it would be equally valid to say that the trip had lasted only a few years or that the trip had lasted thousands of years, depending on the choice of reference frame.

This form of "travel into the future" is theoretically allowed (and has been demonstrated at very small time scales) using the following methods:[31]

- Using velocity-based time dilation under the theory of special relativity, for instance:

- Traveling at almost the speed of light to a distant star, then slowing down, turning around, and traveling at almost the speed of light back to Earth[60] (see the Twin paradox)

- Using gravitational time dilation under the theory of general relativity, for instance:

- Residing inside of a hollow, high-mass object;

- Residing just outside the event horizon of a black hole, or sufficiently near an object whose mass or density causes the gravitational time dilation near it to be larger than the time dilation factor on Earth.

Time dilation

Time dilation is permitted by Albert Einstein's special and general theories of relativity. These theories state that, relative to a given observer, time passes more slowly for bodies moving quickly relative to that observer, or bodies that are deeper within a gravity well.[61] For example, a clock which is moving relative to the observer will be measured to run slow in that observer's rest frame; as a clock approaches the speed of light it will almost slow to a stop, although it can never quite reach light speed so it will never completely stop. For two clocks moving inertially (not accelerating) relative to one another, this effect is reciprocal, with each clock measuring the other to be ticking slower. However, the symmetry is broken if one clock accelerates, as in the twin paradox where one twin stays on Earth while the other travels into space, turns around (which involves acceleration), and returns—in this case both agree the traveling twin has aged less. General relativity states that time dilation effects also occur if one clock is deeper in a gravity well than the other, with the clock deeper in the well ticking more slowly; this effect must be taken into account when calibrating the clocks on the satellites of the Global Positioning System, and it could lead to significant differences in rates of aging for observers at different distances from a black hole.

It has been calculated that, under general relativity, a person could travel forward in time at a rate four times that of distant observers by residing inside a spherical shell with a diameter of 5 meters and the mass of Jupiter.[62] For such a person, every one second of their "personal" time would correspond to four seconds for distant observers. Of course, squeezing the mass of a large planet into such a structure is not expected to be within our technological capabilities in the near future.

There is a great deal of experimental evidence supporting the validity of equations for velocity-based time dilation in special relativity[63] and gravitational time dilation in general relativity.[64][65][66] However, with current technologies it is only possible to cause a human traveler to age less than companions on Earth by a very small fraction of a second, the current record being about 20 milliseconds for the cosmonaut Sergei Avdeyev.

Time perception

Time perception can be apparently sped up for living organisms through hibernation, where the body temperature and metabolic rate of the creature is reduced. A more extreme version of this is suspended animation, where the rates of chemical processes in the subject would be severely reduced.

Time dilation and suspended animation only allow "travel" to the future, never the past, so they do not violate causality, and it is debatable whether they should be called time travel. However time dilation can be viewed as a better fit for our understanding of the term "time travel" than suspended animation, since with time dilation less time actually does pass for the traveler than for those who remain behind, so the traveler can be said to have reached the future faster than others, whereas with suspended animation this is not the case.

Research

It is hypothesized forward time travel could be experimentally proven using circulating lasers instead of super massive objects. If a subatomic particle with a short lifetime were to be observed lasting longer this would suggest it had traveled into the future at an accelerated rate.[67]

Other ideas from mainstream physics

Many-worlds interpretation

Parallel universes might provide a way out of paradoxes. Everett's many-worlds interpretation (MWI) of quantum mechanics suggests that all possible quantum events can occur in mutually exclusive histories.[68] These alternate, or parallel, histories would form a branching tree symbolizing all possible outcomes of any interaction. If all possibilities exist, any paradoxes could be explained by having the paradoxical events happening in a different universe. This concept is most often used in science-fiction, but some physicists such as David Deutsch have suggested that if time travel is possible and the MWI is correct, then a time traveler should indeed end up in a different history than the one he started from.[69][70][71] On the other hand, Stephen Hawking has argued that even if the MWI is correct, we should expect each time traveler to experience a single self-consistent history, so that time travelers remain within their own world rather than traveling to a different one.[26] The physicist Allen Everett argued that Deutsch's approach "involves modifying fundamental principles of quantum mechanics; it certainly goes beyond simply adopting the MWI". Everett also argues that even if Deutsch's approach is correct, it would imply that any macroscopic object composed of multiple particles would be split apart when traveling back in time through a wormhole, with different particles emerging in different worlds.[72]

Daniel Greenberger and Karl Svozil proposed that quantum theory gives a model for time travel without paradoxes.[73][74] The quantum theory observation causes possible states to 'collapse' into one measured state; hence, the past observed from the present is deterministic (it has only one possible state), but the present observed from the past has many possible states until our actions cause it to collapse into one state. Our actions will then be seen to have been inevitable.

Using quantum entanglement

Quantum-mechanical phenomena such as quantum teleportation, the EPR paradox, or quantum entanglement might appear to create a mechanism that allows for faster-than-light (FTL) communication or time travel, and in fact some interpretations of quantum mechanics such as the Bohm interpretation presume that some information is being exchanged between particles instantaneously in order to maintain correlations between particles.[75] This effect was referred to as "spooky action at a distance" by Einstein.

Nevertheless, the fact that causality is preserved in quantum mechanics is a rigorous result in modern quantum field theories, and therefore modern theories do not allow for time travel or FTL communication. In any specific instance where FTL has been claimed, more detailed analysis has proven that to get a signal, some form of classical communication must also be used.[76] The no-communication theorem also gives a general proof that quantum entanglement cannot be used to transmit information faster than classical signals. The fact that these quantum phenomena apparently do not allow FTL time travel is often overlooked in popular press coverage of quantum teleportation experiments. How the rules of quantum mechanics work to preserve causality is an active area of research.

Philosophical understandings of time travel

Theories of time travel are riddled with questions about causality and paradoxes. Compared to other fundamental concepts in modern physics, time is still not understood very well. Philosophers have been theorizing about the nature of time since before the era of the ancient Greek philosophers. Some philosophers and physicists who study the nature of time also study the possibility of time travel and its logical implications. The probability of paradoxes and their possible solutions are often considered.

For more information on the philosophical considerations of time travel, consult the work of David Lewis. For more information on physics-related theories of time travel, consider the work of Kurt Gödel (especially his theorized universe) and Lawrence Sklar.

Presentism vs. eternalism

The relativity of simultaneity in modern physics favors the philosophical view known as eternalism or four-dimensionalism (Sider, 2001), in which physical objects are either temporally extended spacetime worms, or spacetime worm stages, and this view would be favored further by the possibility of time travel (Sider, 2001). Eternalism, also sometimes known as "block universe theory", builds on a standard method of modeling time as a dimension in physics, to give time a similar ontology to that of space (Sider, 2001). This would mean that time is just another dimension, that future events are "already there", and that there is no objective flow of time. This view is disputed by Tim Maudlin in his The Metaphysics Within Physics.

Presentism is a school of philosophy that holds that neither the future nor the past exist, and there are no non-present objects. In this view, time travel is impossible because there is no future or past to travel to. However, some 21st-century presentists have argued that although past and future objects do not exist, there can still be definite truths about past and future events, and thus it is possible that a future truth about a time traveler deciding to travel back to the present date could explain the time traveler's actual appearance in the present.[77][78]

The grandfather paradox

One subject often brought up in philosophical discussion of time is the idea that, if one were able to go back in time, paradoxes could ensue if the time traveler were to change things. The best examples of this are the grandfather paradox and the idea of autoinfanticide. The grandfather paradox is a hypothetical situation in which a time traveler goes back in time and attempts to kill his paternal grandfather at a time before his grandfather met his grandmother. If he did so, then his father never would have been born, and neither would the time traveler himself, in which case the time traveler never would have gone back in time to kill his grandfather.

Autoinfanticide works the same way, where a traveler goes back and attempts to kill himself as an infant. If he were to do so, he never would have grown up to go back in time to kill himself as an infant.

This discussion is important to the philosophy of time travel because philosophers question whether these paradoxes make time travel impossible. Some philosophers answer the paradoxes by arguing that it might be the case that backward time travel could be possible but that it would be impossible to actually change the past in any way,[79] an idea similar to the proposed Novikov self-consistency principle in physics.

Theory of compossibility

David Lewis's analysis of compossibility and the implications of changing the past is meant to account for the possibilities of time travel in a one-dimensional conception of time without creating logical paradoxes. Consider Lewis’ example of Tim. Tim hates his grandfather and would like nothing more than to kill him. The only problem for Tim is that his grandfather died years ago. Tim wants so badly to kill his grandfather himself that he constructs a time machine to travel back to 1955 when his grandfather was young and kill him then. Assuming that Tim can travel to a time when his grandfather is still alive, the question must then be raised: can Tim kill his grandfather?

For Lewis, the answer lies within the context of the usage of the word "can". Lewis explains that the word "can" must be viewed against the context of pertinent facts relating to the situation. Suppose that Tim has a rifle, years of rifle training, a straight shot on a clear day and no outside force to restrain Tim's trigger finger. Can Tim shoot his grandfather? Considering these facts, it would appear that Tim can in fact kill his grandfather. In other words, all of the contextual facts are compossible with Tim killing his grandfather. However, when reflecting on the compossibility of a given situation, we must gather the most inclusive set of facts that we are able to.

Consider now the fact that in Tim's universe his grandfather actually died in 1993 and not in 1955. This new fact about Tim's situation reveals that him killing his grandfather is not compossible with the current set of facts. Tim cannot kill his grandfather because his grandfather died in 1993 and not when he was young. Thus, Lewis concludes, the statements "Tim doesn’t but can, because he has what it takes", and, "Tim doesn’t, and can’t, because it is logically impossible to change the past", are not contradictions; they are both true given the relevant set of facts. The usage of the word "can" is equivocal: he "can" and "can not" under different relevant facts.

So what must happen to Tim as he takes aim? Lewis believes that his gun will jam, a bird will fly in the way, or Tim simply slips on a banana peel. Either way, there will be some logical force of the universe that will prevent Tim every time from killing his grandfather.[80]

Time travel in fiction

Time travel themes in science fiction and the media can generally be grouped into three general categories: immutable timeline; mutable timeline; and alternate histories (as in the many-worlds interpretation).[81][82][83][84] Frequently in fiction, timeline is used to refer to all physical events in history, so that in time travel stories where events can be changed, the time traveler is described as creating a new or altered timeline.[85] This usage is distinct from the use of the term timeline to refer to a type of chart created by humans to illustrate a particular series of events, and the concept is also distinct from a world line, a term from Einstein's theory of relativity which refers to the entire history of a single object.

Immutable timeline

The Novikov self-consistency principle, named after Igor Dmitrievich Novikov, states that the timeline is totally fixed, and any actions taken by a time traveler were part of history all along, so it is impossible for the time traveler to "change" history in any way. The time traveler's actions may be the cause of events in their own past though, which leads to the potential for circular causation and the predestination paradox; for examples of circular causation, see Robert A. Heinlein's story "By His Bootstraps". The Novikov self-consistency principle proposes that the local laws of physics in a region of spacetime containing time travelers cannot be any different from the local laws of physics in any other region of spacetime.[86]

The philosopher Kelley L. Ross argues in "Time Travel Paradoxes"[87] that in an ontological paradox scenario involving a physical object, there can be a violation of the second law of thermodynamics. Ross uses Somewhere in Time as an example where Jane Seymour's character gives Christopher Reeve's character a watch she has owned for many years, and when he travels back in time he gives the same watch to Jane Seymour's character 60 years in the past. As Ross states:

The watch is an impossible object. It violates the Second Law of Thermodynamics, the Law of Entropy. If time travel makes that watch possible, then time travel itself is impossible. The watch, indeed, must be absolutely identical to itself in the 19th and 20th centuries, since Reeve carries it with him from the future instantaneously into the past and bestows it on Seymour. The watch, however, cannot be identical to itself, since all the years in which it is in the possession of Seymour and then Reeve it will wear in the normal manner. Its entropy will increase. The watch carried back by Reeve will be more worn than the watch that would have been acquired by Seymour.

On the other hand, the second law of thermodynamics is understood by modern physicists to be a statistical law rather than an absolute one, so spontaneous reversals of entropy or failure to increase in entropy are not impossible, just improbable (see for example the fluctuation theorem). In addition, the second law of thermodynamics only states that entropy should increase in systems which are isolated from interactions with the external world, so Igor Novikov (creator of the Novikov self-consistency principle) has argued that in the case of macroscopic objects like the watch whose worldlines form closed loops, the outside world can expend energy to repair wear/entropy that the object acquires over the course of its history, so that it will be back in its original condition when it closes the loop.[88]

Mutable timelines

Few if any physicists or philosophers have taken seriously the possibility of "changing" the past except in the case of multiple universes, and in fact many have argued that this idea is logically incoherent,[79] so the mutable timeline idea is rarely considered outside of science fiction.

Time travel or spacetime travel

An objection that is sometimes raised against the concept of time machines in science fiction is that they ignore the motion of the Earth between the date the time machine departs and the date it returns. The idea that a traveler can go into a machine that sends him or her to 1865 and step out into exactly the same spot on Earth might be said to ignore the issue that Earth is moving through space around the Sun, which is moving in the galaxy, and so on, so that advocates of this argument imagine that "realistically" the time machine should actually reappear in space far away from the Earth's position at that date. However, the theory of relativity rejects the idea of absolute time and space; in relativity there can be no universal truth about the spatial distance between events which occur at different times[89] (such as an event on Earth today and an event on Earth in 1865), and thus no objective truth about which point in space at one time is at the "same position" that the Earth was at another time. In the theory of special relativity, which deals with situations where gravity is negligible, the laws of physics work the same way in every inertial frame of reference and therefore no frame's perspective is physically better than any other frame's, and different frames disagree about whether two events at different times happened at the "same position" or "different positions". In the theory of general relativity, which incorporates the effects of gravity, all coordinate systems are on equal footing because of a feature known as "diffeomorphism invariance".[90]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Hawking, Stephen (April 27, 2010). "STEPHEN HAWKING: How to build a time machine". Daily Mail. Retrieved August 7, 2015.

- ↑ "Curiosities : "The Clock That Went Backward," by Edward Page Mitchell (1881)". sfsite.com.

- ↑ Vandermeer. The Time Traveler's Almanac. TOR. pp. 154, 450.

The Clock That Went Backward, released in 1881 in The Sun is the first time-travel story ever published, coming out several years before HG Well's The Time Machine. Although it is popularly believed that The Chronic Argonauts was the first fiction published with a time-travel theme, another story, also in this anthology, predates it by almost a decade: Edward Page Mitchell's The Clock That Went Backward

- ↑ mythfolklore.net, Revati, Encyclopedia for Epics of Ancient India

- ↑ mayapur.com, Lord Balarama, Sri Mayapur Archived December 8, 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Indian Philosophy – Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya: People's Publishing House, New Delhi. (First Published: 1964, 7th Edition: 1993)

- 1 2 Yorke, Christopher (February 2006). "Malchronia: Cryonics and Bionics as Primitive Weapons in the War on Time". Journal of Evolution and Technology 15 (1): 73–85. Retrieved 2009-08-29.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Donna (1997). Folklore, myths, and legends: a world perspective. McGraw-Hill. p. 421. ISBN 0-8442-5780-X.

- ↑ "Choni HaMe'agel". Jewish search. Archived from the original on January 27, 2011. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ↑ Robert Darnton, The Forbidden Best-Sellers of Pre-Revolutionary France (New York: W.W. Norton, 1996), 120.

- 1 2 Alkon, Paul K. (1987). Origins of Futuristic Fiction. The University of Georgia Press. pp. 95–96. ISBN 0-8203-0932-X.

- ↑ Alkon, Paul K. (1987). Origins of Futuristic Fiction. The University of Georgia Press. p. 85. ISBN 0-8203-0932-X.

- ↑ Akutin, Yury (1978) Александр Вельтман и его роман "Странник" (Alexander Veltman and his novel Strannik, in Russian).

- ↑ "Missing One's Coach: An Anachronism". Dublin University magazine 11. March 1838.

- ↑ Derleth, August (1951). Far Boundaries. Pellegrini & Cudahy. p. 3.

- ↑ Derleth, August (1951). Far Boundaries. Pellegrini & Cudahy. pp. 11–38.

- ↑ Flynn, John L. "Time Travel Literature". Archived from the original on 2006-09-29. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- ↑ Rudwick, Martin J. S. (1992). Scenes From Deep Time. The University of Chicago Press. pp. 166–169. ISBN 0-226-73105-7.

- ↑ Nahin, Paul J. (2001). Time machines: time travel in physics, metaphysics, and science fiction. Springer. p. 54. ISBN 0-387-98571-9.

- ↑ Page Mitchell, Edward. "The Clock That Went Backward" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 15, 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ Nahin, Paul J. (2001). Time machines: time travel in physics, metaphysics, and science fiction. Springer. p. 55. ISBN 0-387-98571-9.

- ↑ Uribe, Augusto (June 1999). "The First Time Machine: Enrique Gaspar's Anacronópete". The New York Review of Science Fiction. 11, no. 10 (130): 12.

- ↑ Noted in the Introduction to an English translation of the book, The Time Ship: A Chrononautical Journey, translated by Yolanda Molina-Gavilán and Andrea L. Bell.

- ↑ Westcott, Kathryn. "HG Wells or Enrique Gaspar: Whose time machine was first?". Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 Thorne, Kip S. (1994). Black Holes and Time Warps. W. W. Norton. p. 499. ISBN 0-393-31276-3.

- 1 2 Hawking, Stephen. "Space and Time Warps". Retrieved 2012-02-26.

- ↑ "NOVA Online – Sagan on Time Travel". Pbs.org. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ↑ Visser, Matt (2002). "The quantum physics of chronology protection". arXiv:gr-qc/0204022 [gr-qc].

- ↑ Hawking, Stephen (1992). "Chronology protection conjecture". Physical Review D 46 (2): 603. Bibcode:1992PhRvD..46..603H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.46.603.

- 1 2 Hawking, Stephen; Thorne, Kip; Novikov, Igor; Ferris, Timothy; Lightman, Alan (2002). The Future of Spacetime. W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-02022-3.

- 1 2 Gott, J. Richard (2002). "Time Travel in Einstein's Universe". p.33-130

- 1 2 Jarrell, Mark. "The Special Theory of Relativity" (PDF). pp. 7–11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-13. Retrieved 2006-10-27.

- ↑ "Sharp Blue: Relativity, FTL and causality – Richard Baker". Theculture.org. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ↑ Chase, Scott I. "Tachyons entry from Usenet Physics FAQ". Retrieved 2006-10-27.

- ↑ Visser, Matt (1996). Lorentzian Wormholes. Springer-Verlag. p. 100. ISBN 1-56396-653-0.

- ↑ Thorne, Kip S. (1994). Black Holes and Time Warps. W. W. Norton. p. 502. ISBN 0-393-31276-3.

- ↑ Thorne, Kip S. (1994). Black Holes and Time Warps. W. W. Norton. p. 504. ISBN 0-393-31276-3.

- 1 2 Visser, Matt (1996). Lorentzian Wormholes. Springer-Verlag. p. 101. ISBN 1-56396-653-0.

- ↑ Cramer, John G. "NASA Goes FTL Part 1: Wormhole Physics". Archived from the original on 2006-06-27. Retrieved 2006-12-02.

- ↑ Visser, Matt; Sayan Kar; Naresh Dadhich (2003). "Traversable wormholes with arbitrarily small energy condition violations". Physical Review Letters 90 (20): 201102.1–201102.4. arXiv:gr-qc/0301003. Bibcode:2003PhRvL..90t1102V. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.201102.

- ↑ Visser, Matt (1993). "From wormhole to time machine: Comments on Hawking's Chronology Protection Conjecture". Physical Review D 47 (2): 554–565. arXiv:hep-th/9202090. Bibcode:1993PhRvD..47..554V. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.47.554.

- ↑ Visser, Matt (1997). "Traversable wormholes: the Roman ring". Physical Review D 55 (8): 5212–5214. arXiv:gr-qc/9702043. Bibcode:1997PhRvD..55.5212V. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.55.5212.

- ↑ van Stockum, Willem Jacob (1936). "The Gravitational Field of a Distribution of Particles Rotating about an Axis of Symmetry". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

- ↑ Lanczos, Kornel (1924). "On a Stationary Cosmology in the Sense of Einsteins Theory of Gravitation". General Relativity and Gravitation (Springland Netherlands) 29 (3): 363–399. doi:10.1023/A:1010277120072.

- ↑ Earman, John (1995). Bangs, Crunches, Whimpers, and Shrieks: Singularities and Acausalities in Relativistic Spacetimes. Oxford University Press. p. 21. ISBN 0-19-509591-X.

- ↑ Tipler, Frank J (1974). "Rotating Cylinders and the Possibility of Global Causality Violation". Physical Review D 9 (8): 2203. Bibcode:1974PhRvD...9.2203T. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.9.2203.

- ↑ Earman, John (1995). Bangs, Crunches, Whimpers, and Shrieks: Singularities and Acausalities in Relativistic Spacetimes. Oxford University Press. p. 169. ISBN 0-19-509591-X.

- ↑ Hawking, Stephen (1992). "Chronology protection conjecture". Physical Review D 46 (2): 603–611. Bibcode:1992PhRvD..46..603H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.46.603.

- ↑ Wright, Laura (November 6, 2003). "Score Another Win for Albert Einstein". Discover.

- ↑ Anderson, Mark (August 18–24, 2007). "Light seems to defy its own speed limit". New Scientist 195 (2617). p. 10.

- ↑ ust.hk; The Hong Kong University of Science & Technology. Retrieved 2011-09-05.

- ↑ It's official: Time machines won't work – latimes.com. Los Angeles Times. (2011-07-25). Retrieved 2011-09-05.

- ↑ dailymail.co.uk; Time travel is sci-fi fantasy: Scientists prove nothing can travel faster than the speed of light | Mail Online]. Retrieved 2011-09-05.

- ↑ Franklin, Ben A. (March 11, 1982), "The night the planets were aligned with Baltimore lunacy", The New York Times.

- ↑ "Welcome the People from the Future. March 9, 1982". Ad in Artforum (January 1980) p. 90.

- ↑ "Museum of the Future". Lehman.cuny.edu. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ↑ Jaume Garriga; Alexander Vilenkin (2001). "Many worlds in one". Phys. Rev. D 64 (4): 043511. arXiv:gr-qc/0102010. Bibcode:2001PhRvD..64d3511G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.64.043511.

- ↑ "Taking the Cosmic Shortcut – ABC Science Online". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 2002-02-21. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ↑ "Transcript of interview with Dr. Marc Rayman at "Space Place"". Spaceplace.nasa.gov. 2005-09-08. Archived from the original on June 3, 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ↑ Time Can Vary? pbs.org

- ↑ Serway, Raymond A. (2000) Physics for Scientists and Engineers with Modern Physics, Fifth Edition, Brooks/Cole, p. 1258, ISBN 0030226570.

- ↑ Gott, J. Richard (2002). "Time Travel in Einstein's Universe". p.76-140

- ↑ Roberts, Tom (October 2007). "What is the experimental basis of Special Relativity?". Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- ↑ "Scout Rocket Experiment". Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- ↑ "Hafele-Keating Experiment". Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- ↑ Pogge, Richard W. (27 April 2009). "GPS and Relativity". Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- ↑ Lisa Zyga (Apr 4, 2006). "Professor predicts human time travel this century".

- ↑ Vaidman, Lev. "Many-Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics". Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- ↑ Deutsch, David (1991). "Quantum mechanics near closed timelike curves". Physical Review D 44 (10): 3197–3217. Bibcode:1991PhRvD..44.3197D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.44.3197.

- ↑ See also the discussion in "Quantum Mechanics to the Rescue?" from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy article "Time travel and Modern Physics".

- ↑ Explained here by Dr Pieter Kok: youtube.com.

- ↑ Everett, Allen (2004). "Time travel paradoxes, path integrals, and the many worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics". Physical Review D 69 (124023). arXiv:gr-qc/0410035. Bibcode:2004PhRvD..69l4023E. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.69.124023.

- ↑ Greenberger, Daniel M.; Svozil, Karl (2005). "Quantum Theory Looks at Time Travel". Quo Vadis Quantum Mechanics?. The Frontiers Collection. p. 63. arXiv:quant-ph/0506027. Bibcode:2005quant.ph..6027G. doi:10.1007/3-540-26669-0_4. ISBN 3-540-22188-3.

- ↑ Kettlewell, Julianna (2005-06-17). "New model 'permits time travel'". BBC News. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ↑ Goldstein, Sheldon. "Bohmian Mechanics". Retrieved 2006-10-30.

- ↑ Nielsen, Michael; Chuang, Isaac (2000). Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. Cambridge. p. 28. ISBN 0-521-63235-8.

- ↑ Keller, Simon; Michael Nelson (September 2001). "Presentists should believe in time-travel" (PDF). Australian Journal of Philosophy 79.3 (3): 333–345. doi:10.1080/713931204. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 1, 2013.

- ↑ This view is contested by another contemporary advocate of presentism, Craig Bourne, in his recent book A Future for Presentism, although for substantially different (and more complex) reasons.

- 1 2 see this discussion between two philosophers, for example

- ↑ Lewis, David (1976). "The paradoxes of time travel" (PDF). American Philosophical Quarterly 13: 145–52. arXiv:gr-qc/9603042. Bibcode:1996gr.qc.....3042K.

- ↑ Grey, William (1999). "Troubles with Time Travel". Philosophy (Cambridge University Press) 74 (1): 55–70. doi:10.1017/S0031819199001047.

- ↑ Rickman, Gregg (2004). The Science Fiction Film Reader. Limelight Editions. ISBN 0-87910-994-7.

- ↑ Nahin, Paul J. (2001). Time machines: time travel in physics, metaphysics, and science fiction. Springer. ISBN 0-387-98571-9.

- ↑ Schneider, Susan (2009). Science Fiction and Philosophy: From Time Travel to Superintelligence. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 1-4051-4907-8.

- ↑ Prucher, Jeff (2007) Brave New Words: The Oxford Dictionary of Science Fiction, p. 230.

- ↑ Friedman, John; Michael Morris; Igor Novikov; Fernando Echeverria; Gunnar Klinkhammer; Kip Thorne; Ulvi Yurtsever (1990). "Cauchy problem in spacetimes with closed timelike curves". Physical Review D 42 (6): 1915. Bibcode:1990PhRvD..42.1915F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.42.1915.

- ↑ Kelley L. Ross, "Time Travel Paradoxes"

- ↑ Gott, J. Richard (2001). Time Travel in Einstein's Universe. Houghton Mifflin. p. 23. ISBN 0-395-95563-7.

- ↑ Geroch, Robert (1978). General Relativity From A to B. The University of Chicago Press. p. 124. ISBN 0-226-28863-3.

- ↑ Max Planck Institut für Gravitationsphysik (2005-09-12). "Einstein Online: Actors on a changing stage". Einstein-online.info. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

Bibliography

- Curley, Mallory (2005). Beatle Pete, Time Traveller. Randy Press.

- Davies, Paul (1996). About Time. Pocket Books. ISBN 0-684-81822-1.

- Davies, Paul (2002). How to Build a Time Machine. Penguin Books Ltd. ISBN 0-14-100534-3.

- Gale, Richard M (1968). The Philosophy of Time. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-00042-0.

- Gott, J. Richard (2002). Time Travel in Einstein's Universe: The Physical Possibilities of Travel Through Time. Boston: Mariner Books. ISBN 0-618-25735-7.

- Gribbin, John (1985). In Search of Schrödinger's Cat. Corgi Adult. ISBN 0-552-12555-5.

- Miller, Kristie (2005). "Time travel and the open future". Disputatio 1 (19): 223–232.

- Nahin, Paul J. (2001). Time Machines: Time Travel in Physics, Metaphysics, and Science Fiction. Springer-Verlag New York Inc. ISBN 0-387-98571-9.

- Nahin, Paul J. (1997). Time Travel: A writer's guide to the real science of plausible time travel. Writer's Digest Books. Cincinnati, Ohio. ISBN 0-89879-748-9

- Nikolic, H (2006). "Causal paradoxes: a conflict between relativity and the arrow of time". Foundations of Physics Letters 19 (3): 259. arXiv:gr-qc/0403121. Bibcode:2006FoPhL..19..259N. doi:10.1007/s10702-006-0516-5.

- Pagels, Heinz (1985). Perfect Symmetry, the Search for the Beginning of Time. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-46548-1.

- Pickover, Clifford (1999). Time: A Traveler's Guide. Oxford University Press Inc, USA. ISBN 0-19-513096-0.

- Randles, Jenny (2005). Breaking the Time Barrier. Simon & Schuster Ltd. ISBN 0-7434-9259-5.

- Shore, Graham M (2003). "Constructing Time Machines". Int. J. Mod. Phys. A, Theoretical 18 (23): 4169. arXiv:gr-qc/0210048. Bibcode:2003IJMPA..18.4169S. doi:10.1142/S0217751X03015118.

- Toomey, David (2007). The New Time Travelers: A Journey to the Frontiers of Physics. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06013-3.

- Wittenberg, David (2013). Time Travel: The Popular Philosophy of Narrative. Fordham University Press. ISBN 978-0-823-24997-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Time travel. |

| Look up time travel in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Black holes, Wormholes and Time Travel, a Royal Society Lecture

- How Time Travel Will Work at HowStuffWorks

- Time Travel and Modern Physics at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Time Travel at the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||