Time-weighted return

The time-weighted return (or true time-weighted rate of return (TWROR)) is a measure of the historical performance of an investment portfolio which compensates for external flows. (External flows are net movements of value which result from transfers of cash, securities or other instruments, into or out of the portfolio, with no simultaneous equal and opposite movement of value in the opposite direction, as in the case of a purchase or sale, and which are not income from the investments in the portfolio, such as interest, coupons or dividends.)

To compensate for external flows, the overall time interval under analysis is divided into contiguous sub-periods at each point in time within the overall time period whenever there is an external flow. In general, these sub-periods will be of unequal lengths. The returns over the sub-periods between external flows are linked geometrically (compounded) together, i.e. by multiplying together the growth factors in all the sub-periods. (The growth factor in each sub-period is equal to 1 plus the return over the sub-period.)

Investment managers are judged on investment activity which is under their control. If they have no control over the timing of flows, then compensating for the timing of flows using the true time-weighted return method is a superior measure of the performance of the investment manager.

Formulae

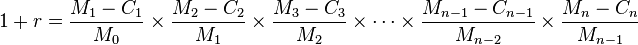

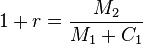

Suppose that the portfolio is valued immediately after each external flow. The value of the portfolio at the end of each sub-period is adjusted for the external flow which takes place immediately before. External flows into the portfolio are considered positive and flows out of the portfolio are negative.

where:

is the "true time-weighted return" of the portfolio,

is the "true time-weighted return" of the portfolio,

is the initial portfolio value,

is the initial portfolio value,

is the portfolio value at the end of sub-period

is the portfolio value at the end of sub-period  , immediately after external flow

, immediately after external flow  ,

,

is the final portfolio value,

is the final portfolio value,

is the net external flow into the portfolio which occurs just before the end of sub-period

is the net external flow into the portfolio which occurs just before the end of sub-period  ,

,

and

is the number of sub-periods.

is the number of sub-periods.

Note that if there is an external flow occurring at the end of the overall period, then the number of sub-periods  matches the number of flows. However, if there is no flow at the end of the overall period, then

matches the number of flows. However, if there is no flow at the end of the overall period, then  is zero, and the number of sub-periods

is zero, and the number of sub-periods  is one greater than the number of flows.

is one greater than the number of flows.

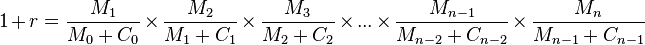

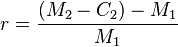

Note also that if the portfolio is valued immediately before each flow instead of immediately after, then each flow should be used to adjust the starting value within each sub-period, instead of the ending value, resulting in a different formula:

where:

is the "true time-weighted return" of the portfolio,

is the "true time-weighted return" of the portfolio,

is the initial portfolio value,

is the initial portfolio value,

is the portfolio value at the end of sub-period

is the portfolio value at the end of sub-period  , immediately before external flow

, immediately before external flow  ,

,

is the final portfolio value,

is the final portfolio value,

is the net external flow into the portfolio which occurs at the beginning of sub-period

is the net external flow into the portfolio which occurs at the beginning of sub-period  ,

,

and

is the number of sub-periods.

is the number of sub-periods.

Adjustment for Flows

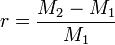

Measuring the performance of a portfolio in the absence of flows is trivial:

where  is the portfolio's final value,

is the portfolio's final value,  is the portfolio's initial value, and

is the portfolio's initial value, and  is the portfolio's return over the period.

is the portfolio's return over the period.

The growth factor is:

External flows during the period being analyzed complicate the performance calculation. If external flows are not taken into account, the performance measurement is distorted: a flow into the portfolio would cause this method to overstate the true performance, while flows out of the portfolio would cause it to understate the true performance.

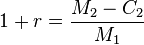

To compensate for an external flow  into the portfolio at the beginning of the period, adjust the portfolio's initial value

into the portfolio at the beginning of the period, adjust the portfolio's initial value  by adding

by adding  . The return is:

. The return is:

and the corresponding growth factor is:

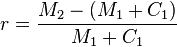

To compensate for an external flow  into the portfolio just before the valuation

into the portfolio just before the valuation  at the end of the period, adjust the portfolio's final value

at the end of the period, adjust the portfolio's final value  by subtracting

by subtracting  . The return is:

. The return is:

and the corresponding growth factor is:

The Problem of External Flows

To illustrate the problem of external flows, consider the following example.

Suppose an investor transfers $500 into a portfolio at the beginning of Year 1, and another $1,000 at the beginning of Year 2, and the portfolio has a total value of $1,500 at the end of the Year 2. The net gain over the two-year period is zero, so intuitively, we might expect that the return over the whole 2-year period to be 0%. If the cash flow of $1,000 at the beginning of Year 2 is ignored, then the simple method of calculating the return without compensating for the flow will be 200% ($1,000 divided by $500). Intuitively, 200% is incorrect.

If we add further information however, a different picture emerges. If the initial investment gained 100% in value over the first year, but the portfolio then declined by 25% during the second year, we would expect the overall return over the two year period to be the result of compounding a 100% gain ($500) with a 25% loss (also $500). The time-weighted return is found by multiplying together the growth factors for each year, i.e. the growth factors before and after the second transfer into the portfolio, then subtracting one, and expressing the result as a percentage:

.

.

We can see from the time-weighted return that the absence of any net gain over the two year period was due to bad timing of the cash inflow at the beginning of the second year.

The time-weighted return appears in this example to overstate the return to the investor, because he sees no net gain. However, by reflecting the performance each year compounded together on an equalized basis, the time-weighted return recognizes the performance of the investment activity independently of the poor timing of the cash flow at the beginning of Year 2. If all the money had been invested at the beginning of Year 1, the return by any measure would most likely have been 50%. $1,500 would have grown by 100% to $3,000 at the end of Year 1, and then declined by 25% to $2,250 at the end of Year 2, resulting in an overall gain of $750, i.e. 50% of $1,500.

Other Returns Methods

Other methods exist to compensate for external flows when calculating investment returns. The time-weighted return is higher than other methods of calculating the investment return when external flows are badly timed - refer to the example immediately above.

Internal Rate of Return

One of these methods is the internal rate of return. Like the true time-weighted return method, the internal rate of return is also based on a compounding principle. It is the discount rate that will set the net present value of all external flows and the terminal value equal to the value of the initial investment. However, solving the equation to find an estimate of the internal rate of return generally requires an iterative numerical method.

The internal rate of return is commonly used for measuring the performance of private equity investments, because the principal partner (the investment manager) has greater control over the timing of cash flows, rather than the limited partner (the end investor).

Simple Dietz Method

The Simple Dietz method[1] applies a simple rate of interest principle, as opposed to the compounding principle underlying the internal rate of return method, and further assumes that flows occur at the midpoint within the time interval (or equivalently that they are distributed evenly throughout the time interval). However, the Simple Dietz method is unsuitable when such assumptions are invalid, and will produce different results to other methods in such a case.

Modified Dietz Method

The Modified Dietz method is another method which, like the Simple Dietz method, applies a simple rate of interest principle. Instead of comparing the gain in value (net of flows) with the initial value of the portfolio, it compares the net gain in value with average capital over the time interval. Average capital allows for the timing of each external flow. As the difference between the Modified Dietz method and the internal rate of return method is that the Modified Dietz method is based on a simple rate of interest principle, whereas the internal rate of return method applies a compounding principle, the two methods produce similar results over short time intervals, if the rates of return are low. Over longer time periods, with significant flows relative to the size of the portfolio, and where the returns are not low, then the differences are more significant.

Linked Returns Methods

Calculating the "true time-weighted return" depends on the availability of portfolio valuations during the investment period. If valuations are not available when each flow occurs, the time-weighted return can only be estimated by linking returns for contiguous sub-periods together geometrically, using sub-periods at the end of which valuations are available. Such an approximate time-weighted return method is prone to overstate or understate the true time-weighted return.

Linked Internal Rate of Return (LIROR) is another such method which is sometimes used to approximate the true time-weighted return. It combines the true time-weighted rate of return method with the internal rate of return (IRR) method. The internal rate of return is estimated over regular time intervals, and then the results are linked geometrically. For example, if the internal rate of return over successive years is 4%, 9%, 5% and 11%, then the LIROR equals 1.04 x 1.09 x 1.05 x 1.11 – 1 = 32.12%. If the regular time periods are not years, then either calculate the un-annualized holding period version of the IRR for each time interval, or calculate the IRR for each time interval firstly, and then convert each one to a holding period return over the time interval, then link together these holding period returns to obtain the LIROR.

Returns Methods in the Absence of Flows

If there are no external flows, then all these methods (time-weighted return, internal rate of return, Modified Dietz Method etc.) give identical results - it is only the various ways they handle flows which makes them different from each other.

Logarithmic Returns

The logarithmic return method is not a competing method of compensating for flows. It is simply the natural logarithm ln(M2/M1) of the growth factor. Refer to the article rate of return.

Fees

To measure returns net of fees, allow the value of the portfolio to be reduced by the amount of the fees. To calculate returns gross of fees, compensate for them by treating them as an external flow, and exclude accrued fees from valuations.

Annual Rate of Return

Any confusion over the meaning of the term return or rate of return should be avoided. The return calculated by these methods is the return per dollar (or per some other unit of currency), not per year (or other unit of time). Annualization, which means conversion to an annual rate of return, is a separate process. Refer to the article rate of return.

See also

- Internal rate of return

- Modified Dietz method

- Rate of return

- Rate of return on a portfolio

- Simple Dietz method

References

- ↑ Dietz, Peter O. Pension Funds: Measuring Investment Performance. Free Press, 1966.

Further reading

- Carl Bacon. Practical Portfolio Performance Measurement and Attribution. West Sussex: Wiley, 2003. ISBN 0-470-85679-3

- Bruce J. Feibel. Investment Performance Measurement. New York: Wiley, 2003. ISBN 0-471-26849-6