Graves' ophthalmopathy

| Graves ophthalmopathy | |

|---|---|

Proptosis and lid retraction from Graves' Disease | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | ophthalmology |

| ICD-10 | H06.2* |

| ICD-9-CM | 242.90 |

| DiseasesDB | 5419 |

| eMedicine | oph/237 ent/169 neuro/476 radio/485 |

| MeSH | D049970 |

Graves' ophthalmopathy (also known as thyroid eye disease (TED), dysthyroid/thyroid-associated orbitopathy (TAO), Graves' orbitopathy) is an autoimmune inflammatory disorder affecting the orbit around the eye, characterized by upper eyelid retraction, lid lag, swelling (edema), redness (erythema), conjunctivitis, and bulging eyes (proptosis).[1]

It is part of a systemic process with variable expression in the eyes, thyroid, and skin, caused by autoantibodies that bind to tissues in those organs, and, in general, occurs with hyperthyroidism.[1] The most common form of hyperthyroidism is Graves' disease. About 10% of cases do not have Graves' disease, but do have autoantibodies.

The autoantibodies target the fibroblasts in the eye muscles, and those fibroblasts can differentiate into fat cells (adipocytes). Fat cells and muscles expand and become inflamed. Veins become compressed, and are unable to drain fluid, causing edema.[1]

Annual incidence is 16/100,000 in women, 3/100,000 in men. About 3-5% have severe disease with intense pain, and sight-threatening corneal ulceration or compression of the optic nerve. Cigarette smoking, which is associated with many autoimmune diseases, raises the incidence 7.7-fold.[1]

Mild disease will often resolve and merely requires measures to reduce discomfort and dryness, such as artificial tears and smoking cessation if possible. Severe cases are a medical emergency, and are treated with glucocorticoids (steroids), and sometimes ciclosporin.[2] Many anti-inflammatory biological mediators, such as infliximab, etanercept, and anakinra are being tried, but there are no randomized controlled trials demonstrating effectiveness.[1]

History

In medical literature, Robert James Graves, in 1835, was the first to describe the association of a thyroid goitre with exophthalmos of the eye.[3] Graves' ophthalmopathy may occur before, with, or after the onset of overt thyroid disease and usually has a slow onset over many months.

Epidemiology

The pathology mostly affects persons of 30 to 50 years of age. Females are four times more likely to develop TAO than males. When males are affected, they tend to have a later onset and a poor prognosis. A study demonstrated that at the time of diagnosis, 90% of the patients with clinical orbitopathy were hyperthyroid according to thyroid function tests, while 3% had Hashimoto's thyroiditis, 1% were hypothyroid and 6% did not have any thyroid function tests abnormality.[4] Of patients with Graves' hyperthyroidism, 20 to 25 percent have clinically obvious Graves' ophthalmopathy, while only 3-5% will develop severe ophthalmopathy.[5][6]

Pathophysiology

TAO is an orbital autoimmune disease. The thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (TSH-R) is an antigen found in orbital fat and connective tissue, and is a target for autoimmune assault. However, some patients with Graves’ orbitopathy present with neither anti-microsomal nor anti-thyroglobulin nor anti-TSH receptor antibodies, the antibodies identified in Graves' disease.

On histological examination, there is an infiltration of the orbital connective tissue by lymphocytes, plasmocytes, and mastocytes. The inflammation results in a deposition of collagen and glycosaminoglycans in the muscles, which leads to subsequent enlargement and fibrosis. There is also an induction of the lipogenesis by fibroblasts and preadipocytes, which causes orbital volume enlargement due to fat deposition. Thyroid eye disease affects between 25-50% of patients with Graves' disease.

Signs and symptoms

In mild disease, patients present with eyelid retraction. In fact, upper eyelid retraction is the most common ocular sign of Graves' orbitopathy. This finding is associated with lid lag on infraduction (Von Graefe's sign), eye globe lag on supraduction (Kocher's sign), a widened palpebral fissure during fixation (Dalrymple's sign) and an incapacity of closing the eyelids completely (lagophthalmos). Due to the proptosis, eyelid retraction and lagophthalmos, the cornea is more prone to dryness and may present with chemosis, punctate epithelial erosions and superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. The patients also have a dysfunction of the lacrimal gland with a decrease of the quantity and composition of tears produced. Non-specific symptoms with these pathologies include irritation, grittiness, photophobia, tearing, and blurred vision. Pain is not typical, but patients often complain of pressure in the orbit. Periorbital swelling due to inflammation can also be observed.

- Eye signs in TED[7]

| Sign | Description |

|---|---|

| Abadie's sign | Elevator muscle of upper eyelid is spastic. |

| Ballett's sign | Paralysis of one or more EOM |

| Beck's sign | Abnormal intense pulsation of retina's arteries |

| Boston's sign | Jerky movements of upper lid on lower gaze |

| Coweh's sign | Extensive hippus of consensual pupillary reflex |

| Dalrymple's sign | Upper eyelid retraction |

| Enroth's sign | Edema esp. of the upper eyelid |

| Gifford's sign | Difficulty in eversion of upper lid. |

| Goldzieher’s sign | Deep injection of conjunctiva, especially temporal |

| Griffith’s sign | Lower lid lag on upward gaze |

| Hertoghe's sign | Loss of eyebrows laterally |

| Jellinek's sign | Superior eyelid folds is hyperpigmented |

| Joffroy’s sign | Absent creases in the fore head on upward gaze. |

| Jendrassik's sign | Abduction and rotation of eyeball is limited also |

| Knies’ sign | Uneven pupillary dilatation in dim light |

| Kocher's sign | Spasmatic retraction of upper lid on fixation |

| Loewi's sign | Quick Mydriasis after instillation of 1:1000 adrenaline |

| Mann's sign | Eyes seem to be situated at different levels because of tanned skin. |

| Means' sign | Increased scleral show on upgaze(globe lag) |

| Moebius's sign | Lack of convergence |

| Payne-Trousseau’s sign | Dislocation of globe |

| Pochin’s sign | Reduced amplitude of blinking |

| Riesman's sign | Bruit over the eyelid |

| Movement's cap phenomenon | Eyeball movements are performed difficultly, abruptly and incompletely |

| Rosenbach's sign | Eyelids are animated by thin tremors when closed |

| Saiton's sign | Frontalis contraction after cessation of levator activity |

| Snellen-Rieseman's sign | When placing the stethoscope's capsule over closed eyelids a systolic murmur could be heard |

| Stellwag's sign | Incomplete and infrequent blinking |

| Suker's sign | Inability to maintain fixation on extreme lateral gaze |

| Tellas's sign | Inferior eyelid might be hyperpigmented |

| Topolanski's sign | Around insertion areas of the four rectus muscles of the eyeball a vascular band network is noticed and this network joints the four insertion points. |

| von Graefe's sign | Upper lid lag on down gaze |

| Wilder's sign | Jerking of the eye on movement from abduction to adduction |

In moderate active disease, the signs and symptoms are persistent and increasing and include myopathy. The inflammation and edema of the extraocular muscles lead to gaze abnormalities. The inferior rectus muscle is the most commonly affected muscle and patient may experience vertical diplopia on upgaze and limitation of elevation of the eyes due to fibrosis of the muscle. This may also increase the intraocular pressure of the eyes. The double vision is initially intermittent but can gradually become chronic. The medial rectus is the second-most-commonly-affected muscle, but multiple muscles may be affected, in an asymmetric fashion.

In more severe and active disease, mass effects and cicatricial changes occur within the orbit. This is manifested by a progressive exophthalmos, a restrictive myopathy that restricts eye movements and an optic neuropathy. With enlargement of the extraocular muscle at the orbital apex, the optic nerve is at risk of compression. The orbital fat or the stretching of the nerve due to increased orbital volume may also lead to optic nerve damage. The patient experiences a loss of visual acuity, visual field defect, afferent pupillary defect, and loss of color vision. This is an emergency and requires immediate surgery to prevent permanent blindness.

Diagnostic

Graves' ophthalmopathy is diagnosed clinically by the presenting ocular signs and symptoms, but positive tests for antibodies (anti-thyroglobulin, anti-microsomal and anti-thyrotropin receptor) and abnormalities in thyroid hormones level (T3, T4, and TSH) help in supporting the diagnosis.

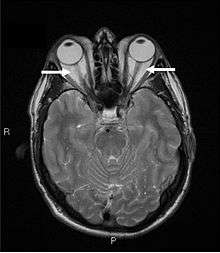

Orbital imaging is an interesting tool for the diagnosis of Graves' ophthalmopathy and is useful in monitoring patients for progression of the disease. It is, however, not warranted when the diagnosis can be established clinically. Ultrasonography may detect early Graves' orbitopathy in patients without clinical orbital findings. It is less reliable than the CT scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), however, to assess the extraocular muscle involvement at the orbital apex, which may lead to blindness. Thus, CT scan or MRI is necessary when optic nerve involvement is suspected. On neuroimaging, the most characteristic findings are thick extraocular muscles with tendon sparing, usually bilateral, and proptosis.

Classification of Graves' eye disease

Mnemonic: "NO SPECS":[8]

| Class | Description |

|---|---|

| Class 0 | No signs or symptoms |

| Class 1 | Only signs (limited to upper lid retraction and stare, with or without lid lag) |

| Class 2 | Soft tissue involvement (oedema of conjunctivae and lids, conjunctival injection, etc.) |

| Class 3 | Proptosis |

| Class 4 | Extraocular muscle involvement (usually with diplopia) |

| Class 5 | Corneal involvement (primarily due to lagophthalmos) |

| Class 6 | Sight loss (due to optic nerve involvement) |

Treatment

Even though some patients undergo spontaneous remission of symptoms within a year, many need treatment. The first step is the regulation of thyroid hormone levels by a physician.

There is some published evidence that a total or sub-total thyroidectomy may assist in reducing levels of TRAB and as a consequence reduce the eye symptoms, perhaps after a 12 month lag.[9][10][11] On the other hand, there is some evidence that suggests that surgery is no better than medication;[12] and there are risks associated with a Thyroidectomy, as there are with long-term use of anti-thyroid medication.

Topical lubrication of the ocular surface is used to avoid corneal damage caused by exposure. Tarsorrhaphy is an alternative option when the complications of ocular exposure can't be avoided solely with the drops.

Corticosteroids are efficient in reducing orbital inflammation, but the benefits cease after discontinuation. Corticosteroids treatment is also limited because of their many side-effects. Radiotherapy is an alternative option to reduce acute orbital inflammation. However, there is still controversy surrounding its efficacy. A simple way of reducing inflammation is smoking cessation, as pro-inflammatory substances are found in cigarettes.

Surgery may be done to decompress the orbit, to improve the proptosis, and to address the strabismus causing diplopia. Surgery is performed once the patient’s disease has been stable for at least six months. In severe cases, however, the surgery becomes urgent to prevent blindness from optic nerve compression. Because the eye socket is bone, there is nowhere for eye muscle swelling to be accommodated, and, as a result, the eye is pushed forward into a protruded position. In some patients, this is very pronounced. Orbital decompression involves removing some bone from the eye socket to open up one or more sinuses and so make space for the swollen tissue and allowing the eye to move back into normal position and also relieving compression of the optic nerve that can threaten sight.

Eyelid surgery is the most common surgery performed on Graves ophthalmopathy patients. Lid-lengthening surgeries can be done on upper and lower eyelid to correct the patient’s appearance and the ocular surface exposure symptoms. Marginal myotomy of levator palpebrae muscle can reduce the palpebral fissure height by 2–3 mm. When there is a more severe upper lid retraction or exposure keratitis, marginal myotomy of levator palpebrae associated with lateral tarsal canthoplasty is recommended. This procedure can lower the upper eyelid by as much as 8 mm. Other approaches include müllerectomy (resection of the Müller muscle), eyelid spacer grafts, and recession of the lower eyelid retractors. Blepharoplasty can also be done to debulk the excess fat in the lower eyelid.[13]

An article in the New England Journal of Medicine reports that treatment with selenium is effective in mild cases. [14]

A large European study performed by the European Group On Graves’ Orbitopathy (EUGOGO) has recently shown that the trace element selenium had a significant effect in patients with mild, active thyroid eye disease. Six months of selenium supplements had a beneficial effect on thyroid eye disease and were associated with improvement in the quality of life of participants. These positive effects persisted at 12 months. There were no side-effects.[15]

One useful summary of treatment recommendations was published recently (in 2015) by an Italian taskforce.,[16] which largely reflects the options above.

Prevention

Not smoking is a common suggestion in the literature. Apart from smoking cessation, there is little definitive research in this area. In addition to the selenium studies above, some recent research also is suggestive that statin use may assist.[10][17]

Poor prognostic indicators

Risk factors of progressive and severe thyroid-associated orbitopathy are:

- Age greater than 50 years

- Rapid onset of symptoms under 3 months

- Cigarette smoking

- Diabetes

- Severe or uncontrolled hyperthyroidism

- Presence of pretibial myxedema

- High cholesterol levels (hyperlipidemia)

- Peripheral vascular disease

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bahn, Rebecca S. (2010). "Graves' Ophthalmopathy". New England Journal of Medicine 362 (8): 726–38. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0905750. PMC 3902010. PMID 20181974.

- ↑ Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 16th Ed., Ch. 320, Disorders of the Thyroid Gland

- ↑ Robert James Graves at Who Named It?

- ↑ Bartley, G. B.; Fatourechi, V; Kadrmas, E. F.; Jacobsen, S. J.; Ilstrup, D. M.; Garrity, J. A.; Gorman, C. A. (1996). "Clinical features of Graves' ophthalmopathy in an incidence cohort". American journal of ophthalmology 121 (3): 284–90. PMID 8597271.

- ↑ Davies, Terry F (September 2009). Ross, Douglas S; Martin, Kathryn A, eds. "Pathogenesis and clinical features of Graves' ophthalmopathy (orbitopathy)". UpToDate.

- ↑ Bartalena, L; Marcocci, C; Pinchera, A (2002). "Graves' ophthalmopathy: A preventable disease?". European Journal of Endocrinology 146 (4): 457–61. doi:10.1530/eje.0.1460457. PMID 11916611.

- ↑ http://www.eophtha.com/eophtha/ppt/Thyroid%20Eye%20diseases.html[]

- ↑ Cawood, T.; Moriarty, P; O'Shea, D (2004). "Recent developments in thyroid eye disease". BMJ 329 (7462): 385–90. doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7462.385. PMC 509348. PMID 15310608.

- ↑ Takamura, Yuuki; Nakano, Keiichi; Uruno, Takashi; Ito, Yasuhiro; Miya, Akihiro; Kobayashi, Kaoru; Yokozawa, Tamotsu; Matsuzuka, Fumio; Kuma, Kanji; Miyauchi, Akira (2003). "Changes in Serum TSH Receptor Antibody (TRAb) Values in Patients with Graves' Disease after Total or Subtotal Thyroidectomy". Endocrine Journal 50 (5): 595–601. doi:10.1507/endocrj.50.595. PMID 14614216.

- 1 2 De Bellis, Annamaria; Conzo, Giovanni; Cennamo, Gilda; Pane, Elena; Bellastella, Giuseppe; Colella, Caterina; Iacovo, Assunta Dello; Paglionico, Vanda Amoresano; Sinisi, Antonio Agostino; Wall, Jack R.; Bizzarro, Antonio; Bellastella, Antonio (2011). "Time course of Graves' ophthalmopathy after total thyroidectomy alone or followed by radioiodine therapy: A 2-year longitudinal study". Endocrine 41 (2): 320–6. doi:10.1007/s12020-011-9559-x. PMID 22169963.

- ↑ Nart, Ahmet; Uslu, Adam; Aykas, Ahmet; Yüzbaşoğlu, Fatih; Doğan, Murat; Demirtaş, Özgür; Şimşek, Cenk (2008). "Total Thyroidectomy for the Treatment of Recurrent Graves' Disease with Ophthalmopathy". Asian Journal of Surgery 31 (3): 115–8. doi:10.1016/S1015-9584(08)60070-6. PMID 18658008.

- ↑ Laurberg, P.; Wallin, G.; Tallstedt, L.; Abraham-Nordling, M.; Lundell, G.; Torring, O. (2007). "TSH-receptor autoimmunity in Graves' disease after therapy with anti-thyroid drugs, surgery, or radioiodine: A 5-year prospective randomized study". European Journal of Endocrinology 158 (1): 69–75. doi:10.1530/EJE-07-0450. PMID 18166819.

- ↑ Muratet JM. "Eyelid retraction". Ophthalmic Plastic Surgery. Le Syndicat National des Ophtalmologistes de France. Archived from the original on June 9, 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-12.

- ↑ Marcocci, Claudio; Kahaly, George J.; Krassas, Gerasimos E.; Bartalena, Luigi; Prummel, Mark; Stahl, Matthias; Altea, Maria Antonietta; Nardi, Marco; Pitz, Susanne; Boboridis, Kostas; Sivelli, Paolo; von Arx, George; Mourits, Maarten P.; Baldeschi, Lelio; Bencivelli, Walter; Wiersinga, Wilmar; European Group on Graves' Orbitopathy (2011). "Selenium and the Course of Mild Graves' Orbitopathy". New England Journal of Medicine 364 (20): 1920–31. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1012985. PMID 21591944.

- ↑ http://www.btf-thyroid.org/index.php/thyroid/research-news/selenium-supplements-and-thyroid[]

- ↑ Bartalena, L.; MacChia, P. E.; Marcocci, C.; Salvi, M.; Vermiglio, F. (2015). "Effects of treatment modalities for Graves' hyperthyroidism on Graves' orbitopathy: A 2015 Italian Society of Endocrinology Consensus Statement". Journal of Endocrinological Investigation 38 (4): 481–7. doi:10.1007/s40618-015-0257-z.

- ↑ Kuehn, Bridget M. (December 15, 2014). "Surgery, Statins Linked to Lower Graves' Complication Risk". Medscape Medical News.

Further reading

- Behbehani, Raed; Sergott, Robert C; Savino, Peter J (2004). "Orbital radiotherapy for thyroid-related orbitopathy". Current Opinion in Ophthalmology 15 (6): 479–82. doi:10.1097/01.icu.0000144388.89867.03. PMID 15523191.

- Boncoeur, M.-P. (2004). "Orbitopathie dysthyroïdienne : imagerie : Orbitopathie dysthyroïdienne" [Imaging techniques in Graves disease : Dysthyroid orbitopathy]. Journal Français d'Ophtalmologie (in French) 27 (7): 815–8. doi:10.1016/S0181-5512(04)96221-3. INIST:16100159.

- Boulos, Patrick Roland; Hardy, Isabelle (2004). "Thyroid-associated orbitopathy: A clinicopathologic and therapeutic review". Current Opinion in Ophthalmology 15 (5): 389–400. doi:10.1097/01.icu.0000139992.15463.1b. PMID 15625899.

- Camezind, P.; Robert, P.-Y.; Adenis, J.-P. (2004). "Signes cliniques de l'orbitopathie dysthyroïdienne : Orbitopathie dysthyroïdienne" [Clinical signs of dysthyroid orbitopathy : Dysthyroid orbitopathy]. Journal Français d'Ophtalmologie (in French) 27 (7): 810–4. doi:10.1016/S0181-5512(04)96220-1. INIST:16100158.

- Duker, Jay S.; Yanoff, Myron (2004). "chapt 95". Ophthalmology (2nd ed.). Saint Louis: C.V. Mosby. ISBN 0-323-02907-8.

- Morax, S.; Ben Ayed, H. (2004). "Techniques et indications chirurgicales des décompressions osseuses de l'orbitopathie dysthyroïdienne" [Orbital decompression for dysthyroid orbitopathy: a review of techniques and indications]. Journal Français d'Ophtalmologie (in French) 27 (7): 828–44. doi:10.1016/s0181-5512(04)96225-0.

- Rose, John G.; Burkat, Cat Nguyen; Boxrud, Cynthia A. (2005). "Diagnosis and Management of Thyroid Orbitopathy". Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America 38 (5): 1043–74. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2005.03.015. PMID 16214573.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||