Thermal wind

Thermal wind is a vertical shear in the geostrophic wind caused by a horizontal temperature gradient. The name is a misnomer, it is not a wind but rather a wind shear.

Description

Physical intuition

Geostrophic wind is proportional to the slope of geopotential on a surface of constant pressure. In a barotropic atmosphere, one where density is a function only of pressure, the slope of isobaric surfaces is independent of temperature, so geostrophic wind does not increase with height.

This does not hold true in a baroclinic atmosphere, where density is a function of both pressure and temperature. Horizontal temperature gradients cause the thickness of gas layers between isobaric surfaces to increase with higher temperatures. When multiple atmospheric layers are stacked upon each other, the slope of isobaric surfaces increases with height. This also causes the magnitude of geostrophic wind to increase with height.

Mathematical formalism

The geopotential thickness of an atmospheric layer is described by the hypsometric equation:

![\Phi_2 - \Phi_1 =\ R \bar{T} \ln \left [ \frac{p_1}{p_2} \right ]](../I/m/f12c2de619a623f9185ad811f8c40f57.png) ,

,

where  is the specific gas constant for air,

is the specific gas constant for air,  is the geopotential at pressure level

is the geopotential at pressure level  , and

, and  is the vertically-averaged temperature of the layer. This formula shows that the layer thickness is proportional to the temperature. When there is a horizontal temperature gradient, the thickness of the layer would be greatest where the temperature is greatest.

is the vertically-averaged temperature of the layer. This formula shows that the layer thickness is proportional to the temperature. When there is a horizontal temperature gradient, the thickness of the layer would be greatest where the temperature is greatest.

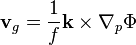

Differentiating the geostrophic wind,  (where

(where  is the Coriolis parameter,

is the Coriolis parameter,  is the vertical unit vector, and the subscript "p" on the gradient operator denotes gradient on a constant pressure surface)

with respect to pressure, and integrate from pressure level

is the vertical unit vector, and the subscript "p" on the gradient operator denotes gradient on a constant pressure surface)

with respect to pressure, and integrate from pressure level  to

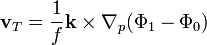

to  , we obtain the thermal wind equation:

, we obtain the thermal wind equation:

.

.

Substituting the hypsometric equation, one gets a form based on temperature,

![\mathbf{v}_T = \frac{R}{f} \ln \left [ \frac{p_0}{p_1}\right ] \mathbf{k} \times \nabla_p \bar{T}](../I/m/4dfbf9743be9b4c09c6c3643717ca1e9.png) .

.

Note that thermal wind is at right angles to the horizontal temperature gradient, counter clockwise in the northern hemisphere. In the southern hemisphere, the change in sign of  flips the direction.

flips the direction.

Examples

Advection turning

If a component of the geostrophic wind is parallel to the temperature gradient, the thermal wind will cause the geostrophic wind to rotate with height. If geostrophic wind blows from cold air to warm air (cold advection) the geostrophic wind will turn counterclockwise with height (for the northern hemisphere), a phenomenon known as wind backing. Otherwise, if geostrophic wind blows from warm air to cold air (warm advection) the wind will turn clockwise with height, also known as wind veering.

Wind backing and veering allow an estimation of the horizontal temperature gradient with data from an atmospheric sounding.

Frontogenesis

As in the case of advection turning, when there is a cross-isothermal component of the geostrophic wind, a sharpening of the temperature gradient results. Thermal wind causes a deformation field and frontogenesis may occur.

Jet stream

A horizontal temperature gradient exists while moving North-South along a meridian because curvature of the Earth allows for more solar heating at the equator than at the poles. This creates a westerly geostrophic wind pattern to form in the mid-latitudes. Because thermal wind causes an increase in wind velocity with height, the westerly pattern increases in intensity up until the tropopause, creating a strong wind current known as the jet stream. The Northern and Southern Hemispheres exhibit similar jet stream patterns in the mid-latitudes.

The strongest part of jet streams should be in proximity where temperature gradients are the largest. Due to land masses in the northern hemisphere, largest temperature contrasts are observed on the east coast of North America (boundary between Canadian cold air mass and the Gulf Stream/warmer Atlantic) and Eurasia (boundary between the boreal winter monsoon/Siberian cold air mass and the warm Pacific). Therefore, the strongest boreal winter northern hemisphere jet streams are observed over east coast of North America and Eurasia. Since stronger vertical shear promotes baroclinic instability, the most rapid development of extratropical cyclones (so called bombs) is also observed along the east coast of North America and Eurasia.

The lack of land masses in the Southern Hemisphere leads to a more constant jet with longitude (i.e. a more zonally symmetric jet).

Further reading

- Holton, James R. (2004). An Introduction to Dynamic Meteorology. New York: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-354015-1.

- Vasquez, Tim (2002). Weather Forecasting Handbook. ISBN 0-9706840-2-9.

- Vallis, Geoffrey K. (2006). Atmospheric and Oceanic Fluid Dynamics. ISBN 0-521-84969-1.

- Wallace, John M.; Hobbs, Peter V. (2006). Atmospheric Science. ISBN 0-12-732951-X.