Thermal conductivity

In physics, thermal conductivity (often denoted k, λ, or κ) is the property of a material to conduct heat. It is evaluated primarily in terms of Fourier's Law for heat conduction.

Heat transfer occurs at a lower rate across materials of low thermal conductivity than across materials of high thermal conductivity. Correspondingly, materials of high thermal conductivity are widely used in heat sink applications and materials of low thermal conductivity are used as thermal insulation. The thermal conductivity of a material may depend on temperature. The reciprocal of thermal conductivity is called thermal resistivity.

Thermal conductivity is actually a tensor, which means it is possible to have different values in different directions. See #Thermal anisotropy below.

Units of thermal conductivity

In SI units, thermal conductivity is measured in watts per meter kelvin (W/(m·K)). The dimension of thermal conductivity is M1L1T−3Θ−1. These variables are (M)mass, (L)length, (T)time, and (Θ)temperature. In Imperial units, thermal conductivity is measured in BTU/(hr·ft⋅°F).[note 1][1]

Other units which are closely related to the thermal conductivity are in common use in the construction and textile industries. The construction industry makes use of units such as the R-value (resistance) and the U-value (conductivity). Although related to the thermal conductivity of a material used in an insulation product, R and U-values are dependent on the thickness of the product.[note 2]

Likewise the textile industry has several units including the tog and the clo which express thermal resistance of a material in a way analogous to the R-values used in the construction industry.

Measurement

There are a number of ways to measure thermal conductivity. Each of these is suitable for a limited range of materials, depending on the thermal properties and the medium temperature. There is a distinction between steady-state and transient techniques.

In general, steady-state techniques are useful when the temperature of the material does not change with time. This makes the signal analysis straightforward (steady state implies constant signals). The disadvantage is that a well-engineered experimental setup is usually needed. The Divided Bar (various types) is the most common device used for consolidated rock solids.

Experimental values

Thermal conductivity is important in material science, research, electronics, building insulation and related fields, especially where high operating temperatures are achieved. Several materials are shown in the list of thermal conductivities. These should be considered approximate due to the uncertainties related to material definitions.

High energy generation rates within electronics or turbines require the use of materials with high thermal conductivity such as copper (see: Copper in heat exchangers), aluminium, and silver. On the other hand, materials with low thermal conductance, such as polystyrene and alumina, are used in building construction or in furnaces in an effort to slow the flow of heat, i.e. for insulation purposes.

Definitions

The reciprocal of thermal conductivity is thermal resistivity, usually expressed in kelvin-meters per watt (K·m·W−1). For a given thickness of a material, that particular construction's thermal resistance and the reciprocal property, thermal conductance, can be calculated. Unfortunately, there are differing definitions for these terms.

Thermal conductivity, k, often depends on temperature. Therefore the definitions listed below make sense when the thermal conductivity is temperature independent. Otherwise an representative mean value has to be considered; for more, see the equations section below.

Conductance

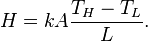

For general scientific use, thermal conductance is the quantity of heat that passes in unit time through a plate of particular area and thickness when its opposite faces differ in temperature by one kelvin. For a plate of thermal conductivity k, area A and thickness L, the conductance calculated is kA/L, measured in W·K−1 (equivalent to: W/°C). The thermal conductance of that particular construction is the inverse of the thermal resistance. Thermal conductivity and conductance are analogous to electrical conductivity (A·m−1·V−1) and electrical conductance (A·V−1).

There is also a measure known as heat transfer coefficient: the quantity of heat that passes in unit time through a unit area of a plate of particular thickness when its opposite faces differ in temperature by one kelvin. The reciprocal is thermal insulance. In summary:

- thermal conductance = kA/L, measured in W·K−1

- thermal resistance = L/(kA), measured in K·W−1 (equivalent to: °C/W)

- heat transfer coefficient = k/L, measured in W·K−1·m−2

- thermal insulance = L/k, measured in K·m2·W−1.

The heat transfer coefficient is also known as thermal admittance in the sense that the material may be seen as admitting heat to flow.

Resistance

Thermal resistance is the ability of a material to resist the flow of heat.

Thermal resistance is the reciprocal of thermal conductance, i.e., lowering its value will raise the heat conduction and vice versa.

When thermal resistances occur in series, they are additive. Thus, when heat flows consecutively through two components each with a resistance of 3 °C/W, the total resistance is 3+3=6 °C/W.

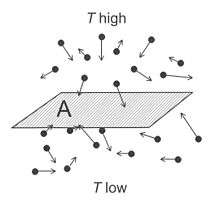

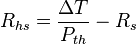

A common engineering design problem involves the selection of an appropriate sized heat sink for a given heat source. Working in units of thermal resistance greatly simplifies the design calculation. The following formula can be used to estimate the performance:

where:

- Rhs is the maximum thermal resistance of the heat sink to ambient, in °C/W (equivalent to K/W)

- ΔT is the required temperature difference (temperature drop), in °C

- Pth is the thermal power (heat flow), in watts

- Rs is the thermal resistance of the heat source, in °C/W

For example, if a component produces 100 W of heat, and has a thermal resistance of 0.5 °C/W, what is the maximum thermal resistance of the heat sink? Suppose the maximum temperature is 125 °C, and the ambient temperature is 25 °C; then ΔT is 100 °C. The heat sink's thermal resistance to ambient must then be 0.5 °C/W or less (total resistance component and heat sink is then 1.0 °C/W).

Transmittance

A third term, thermal transmittance, quantifies the thermal conductance of a structure along with heat transfer due to convection and radiation. It is measured in the same units as thermal conductance and is sometimes known as the composite thermal conductance. The term U-value is often used.

Admittance

The thermal admittance of a material, such as a building fabric, is a measure of the ability of a material to transfer heat in the presence of a temperature difference on opposite sides of the material. Thermal admittance is measured in the same units as a heat transfer coefficient, power (watts) per unit area (square meters) per temperature change (kelvin). Thermal admittance of a building fabric affects a building's thermal response to variation in outside temperature.[2]

Influencing factors

Temperature

The effect of temperature on thermal conductivity is different for metals and nonmetals. In metals conductivity is primarily due to free electrons. Following the Wiedemann–Franz law, thermal conductivity of metals is approximately proportional to the absolute temperature (in kelvin) times electrical conductivity. In pure metals the electrical conductivity decreases with increasing temperature and thus the product of the two, the thermal conductivity, stays approximately constant. In alloys the change in electrical conductivity is usually smaller and thus thermal conductivity increases with temperature, often proportionally to temperature.

On the other hand, heat conductivity in nonmetals is mainly due to lattice vibrations (phonons). Except for high quality crystals at low temperatures, the phonon mean free path is not reduced significantly at higher temperatures. Thus, the thermal conductivity of nonmetals is approximately constant at high temperatures. At low temperatures well below the Debye temperature, thermal conductivity decreases, as does the heat capacity.

Chemical phase

When a material undergoes a phase change from solid to liquid or from liquid to gas the thermal conductivity may change. An example of this would be the change in thermal conductivity that occurs when ice (thermal conductivity of 2.18 W/(m·K) at 0 °C) melts to form liquid water (thermal conductivity of 0.56 W/(m·K) at 0 °C).[3]

Thermal anisotropy

Some substances, such as non-cubic crystals, can exhibit different thermal conductivities along different crystal axes, due to differences in phonon coupling along a given crystal axis. Sapphire is a notable example of variable thermal conductivity based on orientation and temperature, with 35 W/(m·K) along the C-axis and 32 W/(m·K) along the A-axis.[4] Wood generally conducts better along the grain than across it.

When anisotropy is present, the direction of heat flow may not be exactly the same as the direction of the thermal gradient.

Electrical conductivity

In metals, thermal conductivity approximately tracks electrical conductivity according to the Wiedemann–Franz law, as freely moving valence electrons transfer not only electric current but also heat energy. However, the general correlation between electrical and thermal conductance does not hold for other materials, due to the increased importance of phonon carriers for heat in non-metals. Highly electrically conductive silver is less thermally conductive than diamond, which is an electrical insulator, but due to its orderly array of atoms it is conductive of heat via phonons.

Magnetic field

The influence of magnetic fields on thermal conductivity is known as the Righi-Leduc effect.

Convection

Air and other gases are generally good insulators, in the absence of convection. Therefore, many insulating materials function simply by having a large number of gas-filled pockets which prevent large-scale convection. Examples of these include expanded and extruded polystyrene (popularly referred to as "styrofoam") and silica aerogel, as well as warm clothes. Natural, biological insulators such as fur and feathers achieve similar effects by dramatically inhibiting convection of air or water near an animal's skin.

Light gases, such as hydrogen and helium typically have high thermal conductivity. Dense gases such as xenon and dichlorodifluoromethane have low thermal conductivity. An exception, sulfur hexafluoride, a dense gas, has a relatively high thermal conductivity due to its high heat capacity. Argon, a gas denser than air, is often used in insulated glazing (double paned windows) to improve their insulation characteristics.

Physical origins

Heat flux is exceedingly difficult to control and isolate in a laboratory setting. At the atomic level, there are no simple, correct expressions for thermal conductivity. Atomically, the thermal conductivity of a system is determined by how atoms composing the system interact. There are two different approaches for calculating the thermal conductivity of a system.

- The first approach employs the Green-Kubo relations. Although this employs analytic expressions, which, in principle, can be solved, calculating the thermal conductivity of a dense fluid or solid using this relation requires the use of molecular dynamics computer simulation.

- The second approach is based on the relaxation time approach. Due to the anharmonicity within the crystal potential, the phonons in the system are known to scatter. There are three main mechanisms for scattering:

- Boundary scattering, a phonon hitting the boundary of a system;

- Mass defect scattering, a phonon hitting an impurity within the system and scattering;

- Phonon-phonon scattering, a phonon breaking into two lower energy phonons or a phonon colliding with another phonon and merging into one higher-energy phonon.

Lattice waves

Heat transport in both amorphous and crystalline dielectric solids is by way of elastic vibrations of the lattice (phonons). This transport mode is limited by the elastic scattering of acoustic phonons at lattice defects. These predictions were confirmed by the experiments of Chang and Jones on commercial glasses and glass ceramics, where the mean free paths were limited by "internal boundary scattering" to length scales of 10−2 cm to 10−3 cm.[5][6]

The phonon mean free path has been associated directly with the effective relaxation length for processes without directional correlation. If Vg is the group velocity of a phonon wave packet, then the relaxation length  is defined as:

is defined as:

where t is the characteristic relaxation time. Since longitudinal waves have a much greater phase velocity than transverse waves, Vlong is much greater than Vtrans, and the relaxation length or mean free path of longitudinal phonons will be much greater. Thus, thermal conductivity will be largely determined by the speed of longitudinal phonons.[5][7]

Regarding the dependence of wave velocity on wavelength or frequency (dispersion), low-frequency phonons of long wavelength will be limited in relaxation length by elastic Rayleigh scattering. This type of light scattering from small particles is proportional to the fourth power of the frequency. For higher frequencies, the power of the frequency will decrease until at highest frequencies scattering is almost frequency independent. Similar arguments were subsequently generalized to many glass forming substances using Brillouin scattering.[8][9][10][11]

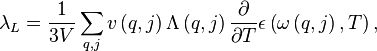

Phonons in the acoustical branch dominate the phonon heat conduction as they have greater energy dispersion and therefore a greater distribution of phonon velocities. Additional optical modes could also be caused by the presence of internal structure (i.e., charge or mass) at a lattice point; it is implied that the group velocity of these modes is low and therefore their contribution to the lattice thermal conductivity λL ( L) is small.[12]

L) is small.[12]

Each phonon mode can be split into one longitudinal and two transverse polarization branches. By extrapolating the phenomenology of lattice points to the unit cells it is seen that the total number of degrees of freedom is 3pq when p is the number of primitive cells with q atoms/unit cell. From these only 3p are associated with the acoustic modes, the remaining 3p(q-1) are accommodated through the optical branches. This implies that structures with larger p and q contain a greater number of optical modes and a reduced λL.

From these ideas, it can be concluded that increasing crystal complexity, which is described by a complexity factor CF (defined as the number of atoms/primitive unit cell), decreases λL. Micheline Roufosse and P.G. Klemens derived the exact proportionality in their article Thermal Conductivity of Complex Dielectric Crystals at Phys. Rev. B 7, 5379–5386 (1973). This was done by assuming that the relaxation time τ decreases with increasing number of atoms in the unit cell and then scaling the parameters of the expression for thermal conductivity in high temperatures accordingly.[12]

Describing of anharmonic effects is complicated because exact treatment as in the harmonic case is not possible and phonons are no longer exact eigensolutions to the equations of motion. Even if the state of motion of the crystal could be described with a plane wave at a particular time, its accuracy would deteriorate progressively with time. Time development would have to be described by introducing a spectrum of other phonons, which is known as the phonon decay. The two most important anharmonic effects are the thermal expansion and the phonon thermal conductivity.

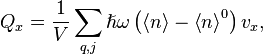

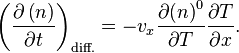

Only when the phonon number ‹n› deviates from the equilibrium value ‹n›0, can a thermal current arise as stated in the following expression

where v is the energy transport velocity of phonons. Only two mechanisms exist that can cause time variation of ‹n› in a particular region. The number of phonons that diffuse into the region from neighboring regions differs from those that diffuse out, or phonons decay inside the same region into other phonons. A special form of the Boltzmann equation

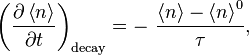

states this. When steady state conditions are assumed the total time derivate of phonon number is zero, because the temperature is constant in time and therefore the phonon number stays also constant. Time variation due to phonon decay is described with a relaxation time (τ) approximation

which states that the more the phonon number deviates from its equilibrium value, the more its time variation increases. At steady state conditions and local thermal equilibrium are assumed we get the following equation

Using the relaxation time approximation for the Boltzmann equation and assuming steady-state conditions, the phonon thermal conductivity λL can be determined. The temperature dependence for λL originates from the variety of processes, whose significance for λL depends on the temperature range of interest. Mean free path is one factor that determines the temperature dependence for λL, as stated in the following equation

where Λ is the mean free path for phonon and  denotes the heat capacity. This equation is a result of combining the four previous equations with each other and knowing that

denotes the heat capacity. This equation is a result of combining the four previous equations with each other and knowing that  for cubic or isotropic systems and

for cubic or isotropic systems and  .[13]

.[13]

At low temperatures (<10 K) the anharmonic interaction does not influence the mean free path and therefore, the thermal resistivity is determined only from processes for which q-conservation does not hold. These processes include the scattering of phonons by crystal defects, or the scattering from the surface of the crystal in case of high quality single crystal. Therefore, thermal conductance depends on the external dimensions of the crystal and the quality of the surface. Thus, temperature dependence of λL is determined by the specific heat and is therefore proportional to T3.[13]

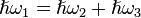

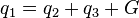

Phonon quasimomentum is defined as ℏq and differs from normal momentum because it is only defined within an arbitrary reciprocal lattice vector. At higher temperatures (10 K<T <Θ), the conservation of energy  and quasimomentum

and quasimomentum  , where q1 is wave vector of the incident phonon and q2, q3 are wave vectors of the resultant phonons, may also involve a reciprocal lattice vector G complicating the energy transport process. These processes can also reverse the direction of energy transport.

, where q1 is wave vector of the incident phonon and q2, q3 are wave vectors of the resultant phonons, may also involve a reciprocal lattice vector G complicating the energy transport process. These processes can also reverse the direction of energy transport.

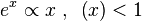

Therefore, these processes are also known as Umklapp (U) processes and can only occur when phonons with sufficiently large q-vectors are excited, because unless the sum of q2 and q3 points outside of the Brillouin zone the momentum is conserved and the process is normal scattering (N-process). The probability of a phonon to have energy E is given by the Boltzmann distribution  . To U-process to occur the decaying phonon to have a wave vector q1 that is roughly half of the diameter of the Brillouin zone, because otherwise quasimomentum would not be conserved.

. To U-process to occur the decaying phonon to have a wave vector q1 that is roughly half of the diameter of the Brillouin zone, because otherwise quasimomentum would not be conserved.

Therefore, these phonons have to possess energy of  , which is a significant fraction of Debye energy that is needed to generate new phonons. The probability for this is proportional to

, which is a significant fraction of Debye energy that is needed to generate new phonons. The probability for this is proportional to  , with

, with  . Temperature dependence of the mean free path has an exponential form

. Temperature dependence of the mean free path has an exponential form  . The presence of the reciprocal lattice wave vector implies a net phonon backscattering and a resistance to phonon and thermal transport resulting finite λL,[12] as it means that momentum is not conserved. Only momentum non-conserving processes can cause thermal resistance.[13]

. The presence of the reciprocal lattice wave vector implies a net phonon backscattering and a resistance to phonon and thermal transport resulting finite λL,[12] as it means that momentum is not conserved. Only momentum non-conserving processes can cause thermal resistance.[13]

At high temperatures (T>Θ) the mean free path and therefore λL has a temperature dependence T−1, to which one arrives from formula  by making the following approximation

by making the following approximation  and writing

and writing  . This dependency is known as Eucken's law and originates from the temperature dependency of the probability for the U-process to occur.[12][13]

. This dependency is known as Eucken's law and originates from the temperature dependency of the probability for the U-process to occur.[12][13]

Thermal conductivity is usually described by the Boltzmann equation with the relaxation time approximation in which phonon scattering is a limiting factor. Another approach is to use analytic models or molecular dynamics or Monte Carlo based methods to describe thermal conductivity in solids.

Short wavelength phonons are strongly scattered by impurity atoms if an alloyed phase is present, but mid and long wavelength phonons are less affected. Mid and long wavelength phonons carry significant fraction of heat, so to further reduce lattice thermal conductivity one has to introduce structures to scatter these phonons. This is achieved by introducing interface scattering mechanism, which requires structures whose characteristic length is longer than that of impurity atom. Some possible ways to realize these interfaces are nanocomposites and embedded nanoparticles/structures.[14]

Electronic thermal conductivity

Hot electrons from higher energy states carry more thermal energy than cold electrons, while electrical conductivity is rather insensitive to the energy distribution of carriers because the amount of charge that electrons carry, does not depend on their energy. This is a physical reason for the greater sensitivity of electronic thermal conductivity to energy dependence of density of states and relaxation time, respectively.[12]

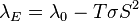

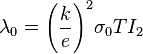

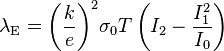

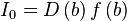

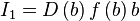

Mahan and Sofo (PNAS 1996 93 (15) 7436-7439) showed that materials with a certain electron structure have reduced electron thermal conductivity. Based on their analysis one can demonstrate that if the electron density of states in the material is close to the delta-function, the electronic thermal conductivity drops to zero. By taking the following equation  , where λ0 is the electronic thermal conductivity when the electrochemical potential gradient inside the sample is zero, as a starting point. As next step the transport coefficients are written as following

, where λ0 is the electronic thermal conductivity when the electrochemical potential gradient inside the sample is zero, as a starting point. As next step the transport coefficients are written as following

,

,

,

,

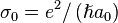

where  and a0 the Bohr radius. The dimensionless integrals In are defined as

and a0 the Bohr radius. The dimensionless integrals In are defined as

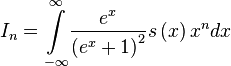

,

,

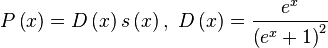

where s(x) is the dimensionless transport distribution function. The integrals In are the moments of the function

,

,

where x is the energy of carriers. By substituting the previous formulas for the transport coefficient to the equation for λE we get the following equation

.

.

From the previous equation we see that λE to be zero the bracketed term containing In terms have to be zero. Now if we assume that

,

,

where δ is the Dirac delta function, In terms get the following expressions

,

, ,

, .

.

By substituting these expressions to the equation for λE, we see that it goes to zero. Therefore, P(x) has to be delta function.[14]

Equations

In an isotropic medium the thermal conductivity is the parameter k in the Fourier expression for the heat flux

where  is the heat flux (amount of heat flowing per second and per unit area) and

is the heat flux (amount of heat flowing per second and per unit area) and  the temperature gradient. The sign in the expression is chosen so that always k > 0 as heat always flows from a high temperature to a low temperature. This is a direct consequence of the second law of thermodynamics.

the temperature gradient. The sign in the expression is chosen so that always k > 0 as heat always flows from a high temperature to a low temperature. This is a direct consequence of the second law of thermodynamics.

In the one-dimensional case q = H/A with H the amount of heat flowing per second through a surface with area A and the temperature gradient is dT/dx so

In case of a thermally-insulated bar (except at the ends) in the steady state H is constant. If A is constant as well the expression can be integrated with the result

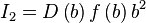

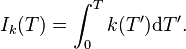

where TH and TL are the temperatures at the hot end and the cold end respectively, and L is the length of the bar. It is convenient to introduce the thermal-conductivity integral

The heat flow rate is then given by

If the temperature difference is small k can be taken as constant. In that case

Simple kinetic picture

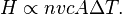

In this Section we will derive an expression for the thermal conductivity. Consider a gas with hard-core interactions but negligible volume within a vertical temperature gradient. The upper side is hot and the lower side cold. There is a downward energy flow because the gas atoms, going down, have a higher energy than the atoms going up. The net flow of energy per second is the heat flow H. The heat flow is proportional to the number of particles that cross the area A per second. This number is proportional to the product nvA where n is the particle density and v the mean particle velocity. The magnitude of the heat flow will also be proportional to amount of energy transported per particle so with the heat capacity per particle c and some characteristic temperature difference ΔT. So far we have

The unit of H is J/s and of the right-hand side it is (particle/m3)•(m/s)•(J/(K•particle))•(m2)•(K) = J/s, so this is already of the right dimension. Only a numerical factor is missing. For ΔT we take the temperature difference of the gas between two collisions

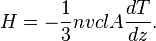

where l is the mean free path. Detailed kinetic calculations[15] show that the numerical factor is -1/3, so, all in all,

Comparison with the one-dimension expression for the heat flow, given above, gives as the final result

The particle density and the heat capacity per particle can be combined as the heat capacity per unit volume

so

where CV is the molar heat capacity at constant volume and Vm the molar volume.

For the hard-core gas the mean free path is given by

where σ is the collision cross section. So

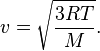

The heat capacity per particle c and the cross section σ both are temperature independent so the temperature dependence of k is determined by the T dependence of v. For a monatomic gas, with atomic mass M, v is given by

So

This expression also shows why gases with a low mass (hydrogen, helium) have a high thermal conductivity.

For metals at low temperatures the heat is carried mainly by the free electrons. In this case the mean velocity is the Fermi velocity which is temperature independent. The mean free path is determined by the impurities and the crystal imperfections which are temperature independent as well. So the only temperature-dependent quantity is the heat capacity c, which, in this case, is proportional to T. So

with k0 a constant. For pure metals such as copper, silver, etc. l is large, so the thermal conductivity is high. At higher temperatures the mean free path is limited by the phonons, so the thermal conductivity tends to decrease with temperature. In alloys the density of the impurities is very high, so l and, consequently k, are small. Therefore, alloys, such as stainless steel, can be used for thermal insulation.

See also

- Copper in heat exchangers

- Heat transfer

- Heat transfer mechanisms

- Insulated pipes

- Interfacial thermal resistance

- Laser flash analysis

- Specific heat

- Thermal bridge

- Thermal conductance quantum

- Thermal contact conductance

- Thermal diffusivity

- Thermal rectifier

- Thermal resistance in electronics

- Thermistor

- Thermocouple

References

- Notes

- References

- ↑ Perry, R. H.; Green, D. W., eds. (1997). Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill. Table 1–4. ISBN 978-0-07-049841-9.

- ↑ "Thermal Mass in Buildings". Reidsteel. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- ↑ NIST: Standard reference data for the thermal conductivity of water

- ↑ "Sapphire, Al2O3". Almaz Optics. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- 1 2 Klemens, P.G. (1951). "The Thermal Conductivity of Dielectric Solids at Low Temperatures". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London A 208 (1092): 108. Bibcode:1951RSPSA.208..108K. doi:10.1098/rspa.1951.0147.

- ↑ Chan, G. K.; Jones, R. E. (1962). "Low-Temperature Thermal Conductivity of Amorphous Solids". Physical Review 126 (6): 2055. Bibcode:1962PhRv..126.2055C. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.126.2055.

- ↑ Pomeranchuk, I. (1941). "Thermal conductivity of the paramagnetic dielectrics at low temperatures". Journal of Physics (Moscow) 4: 357. ISSN 0368-3400.

- ↑ Zeller, R. C.; Pohl, R. O. (1971). "Thermal Conductivity and Specific Heat of Non-crystalline Solids". Physical Review B 4 (6): 2029. Bibcode:1971PhRvB...4.2029Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.4.2029.

- ↑ Love, W. F. (1973). "Low-Temperature Thermal Brillouin Scattering in Fused Silica and Borosilicate Glass". Physical Review Letters 31 (13): 822. Bibcode:1973PhRvL..31..822L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.31.822.

- ↑ Zaitlin, M. P.; Anderson, M. C. (1975). "Phonon thermal transport in noncrystalline materials". Physical Review B 12 (10): 4475. Bibcode:1975PhRvB..12.4475Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.12.4475.

- ↑ Zaitlin, M. P.; Scherr, L. M.; Anderson, M. C. (1975). "Boundary scattering of phonons in noncrystalline materials". Physical Review B 12 (10): 4487. Bibcode:1975PhRvB..12.4487Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.12.4487.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pichanusakorn, P.; Bandaru, P. (2010). "Nanostructured thermoelectrics". Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports 67 (2–4): 19–63. doi:10.1016/j.mser.2009.10.001.

- 1 2 3 4 Ibach, H.; Luth, H. (2009). Solid-State Physics: An Introduction to Principles of Materials Science. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-93803-3.

- 1 2 Minnich, A. J.; Dresselhaus, M. S.; Ren, Z. F.; Chen, G. (2009). "Bulk nanostructured thermoelectric materials: Current research and future prospects". Energy & Environmental Science 2 (5): 466–479. doi:10.1039/b822664b.

- ↑ Kittel, C.; Kroemer, H. (1980). Thermal Physics. W. H. Freeman and Company. Chapter 14. ISBN 978-0716710882.

Further reading

- Callister, William (2003). "Appendix B". Materials Science and Engineering - An Introduction. John Wiley & Sons. p. 757. ISBN 0-471-22471-5.

- Halliday, David; Resnick, Robert; & Walker, Jearl(1997). Fundamentals of Physics (5th ed.). John Wiley and Sons, New York ISBN 0-471-10558-9.

- Srivastava G. P (1990), The Physics of Phonons. Adam Hilger, IOP Publishing Ltd, Bristol.

- TM 5-852-6 AFR 88-19, Volume 6 (Army Corp of Engineers publication)

- Reid, C. R., Prausnitz, J. M., Poling B. E., Properties of gases and liquids, IV edition, Mc Graw-Hill, 1987

- R. Joven, R. Das, A. Ahmed, P. Roozbehjavan, B. Minaie, "Thermal properties of carbon fiber/epoxy composites with different fabric weaves ", in: SAMPE International Symposium Proceedings, Charleston, SC; 2012

External links

- Thermopedia

- J Chem Phys thermal conductivity of electrolyte solutions

- The importance of Soil Thermal Conductivity for power companies

- J Chem Phys gas mixtures

![H= \frac{A}{L}[I_k(T_H)-I_k(T_L)].](../I/m/32c1407902faf64bbbf969e0b22ed052.png)