Baths of Caracalla

| Baths of Caracalla | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Location | Regione XII Piscina Publica |

| Built in | 212-217 AD |

| Built by/for | Caracalla |

| Type of structure | Thermae |

Baths of Caracalla | |

The Baths of Caracalla (Italian: Terme di Caracalla) in Rome, Italy, were the second largest Roman public baths, or thermae, built in Rome between AD 212 and 217, during the reigns of Septimius Severus and Caracalla.[1] Chris Scarre provides a slightly longer construction period 211–217 AD.[2] They would have had to install over 2,000 tons of material every day for six years in order to complete it in this time. Records show that the idea for the baths were drawn up by Septimius Severus, and merely completed or opened in the lifetime of Caracalla.[3] This would allow for a longer construction timeframe. They are today a tourist attraction.

History

The baths remained in use until the 6th century when the complex was taken by the Ostrogoths during the Gothic War, at which time the hydraulic installations were destroyed.[4] The bath was free and open to the public. The building was heated by a hypocaust, a system of burning coal and wood underneath the ground to heat water provided by a dedicated aqueduct. It was in use up to the 19th century. The Aqua Marcia aqueduct by Caracalla was specifically built to serve the baths. It was most likely reconstructed by Garbrecht and Manderscheid to its current place.

In the 19th and early 20th century, the design of the baths was used as the inspiration for several modern structures, including St George's Hall in Liverpool and the original Pennsylvania Station (demolished in 1963) in New York City. At the 1960 Summer Olympics, the venue hosted the gymnastics events.

The baths were the only archaeological site in Rome damaged by an earthquake near L'Aquila in 2009.[5]

The baths were originally ornamented with high quality sculptures. Among the well-known pieces recovered from the Baths of Caracalla are the Farnese Bull and Farnese Hercules, now in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples; others are in the Museo di Capodimonte there. One of the many statues is the colossal 4 m statue of Asclepius.

Interior

The Caracalla bath complex of buildings was more a leisure centre than just a series of baths. The "baths" were the second to have a public library within the complex. Like other public libraries in Rome, there were two separate and equal sized rooms or buildings; one for Greek language texts and one for Latin language texts.

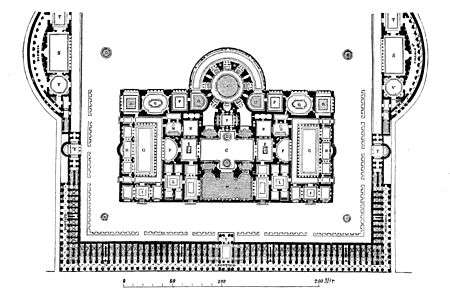

The baths consisted of a central frigidarium (cold room) measuring 55.7 by 24 metres (183x79 ft) under three groin vaults 32.9 metres (108 ft) high, a double pool tepidarium (medium), and a caldarium (hot room) 35 metres (115 ft) in diameter, as well as two palaestras (gyms where wrestling and boxing were practiced). The north end of the bath building contained a natatio or swimming pool. The natatio was roofless with bronze mirrors mounted overhead to direct sunlight into the pool area. The entire bath building was on a raised platform 6 metres (20 ft) high to allow for storage and furnaces under the building.[6]

The libraries were located in exedrae on the east and west sides of the bath complex. The entire north wall of the complex was devoted to shops. The reservoirs on the south wall of the complex were fed with water from the Marcian Aqueduct.[6]

Dimensions

Principal dimensions

Precinct maximum: 412x393 m

Internal: 323x323 m

Central Block overall: 218x112 m

Swimming Pool: 54x23 m

Frigidarium: 59x24 m, height c. 41 m

Caldarium: 35M diameter height c. 44 m

Internal courts: 67x29 m

Quantities of materials

Pozzolana: 341,000 m³

Quick lime: 35,000 m³

Tuff: 341,000 m³

Basalt for foundations: 150,000 m³

Brick pieces for facing: 17.5 million

Large Bricks: 520,000

Marble columns in Central block: 252

Marble for columns and decorations: 6,300 m³

Estimated average labour figures on site

Excavation: 5,200 men

Substructure: 9,500 men

Central Block: 4,500 men

Decoration: 1,800 men

The 12 m columns of the frigidarium were made of granite and they weighed close to 100 tons.

Grounds

The bath complex covered approximately 25 hectares (62 ac). The bath building was 228 metres (750 ft) long, 116 metres (380 ft) wide and 38.5 metres (125 ft) estimated height, and could hold an estimated 1,600 bathers.[6]

Public use in culture

Opera and concerts

The central part of the bath complex is the summer home of the Rome Opera company. It is also a concert venue, having achieved fame as the venue and backdrop for the first Three Tenors concert in 1990.

Sporting

The area was used for the Rome Grand Prix four times between 1947 and 1951.

Visiting

The extensive ruins of the baths have become a popular tourist attraction. The baths are open to the public for an admission fee. Access is limited to certain areas to avoid damage to the mosaic floors, although such damage is already clearly visible. Also, a total of 22 well-preserved columns from the ruins are found in the church of Santa Maria in Trastevere, taken there in the 12th century.

See also

References

- ↑ http://www.crystalinks.com/romebaths.html

- ↑ "Seventy Wonders of the Ancient World" edited by Chris Scarre 1999 p178

- ↑ Walker, Charles, 1980 Wonders of the Ancient World p. 92-3

- ↑ http://www.rome-guide.it/english/monuments/monuments_caracalla.html

- ↑ "L'Aquila earthquake damaged ancient baths inh Rome". Telegraph.co.uk. 2009-04-06. Archived from the original on 9 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- 1 2 3 Roth, Leland M. (1993). Understanding Architecture: Its Elements, History and Meaning (First ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 0-06-430158-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Baths of Caracalla. |

- 1960 Summer Olympics official report. Volume 1. pp. 76, 79.

- 1960 Summer Olympic official report. Volume 2. Part 1. p. 345.

- History Channel website for ROME: Engineering an Empire video tour and Flash presentation on the Baths. Also video gallery for a short movie on the Baths.

- Baths of Caracalla Virtual 360° panorama and photos of the ruins.

- Caracalla Thermal Baths

- 'Restoration of Roman tunnels gives a slave's view of Caracalla Baths,' Tom Kington, The Guardian, 11 December 2012

Coordinates: 41°52′46″N 12°29′35″E / 41.879444°N 12.493056°E

| ||||||

| ||||||||

_pictogram.svg.png)