Refugees of the Greek Civil War

Political refugees of the Greek Civil War were members or sympathisers of the defeated communist forces who fled Greece during or in the aftermath of the Civil War of 1946–1949. The collapse of the Democratic Army of Greece (DSE) and the evacuation of the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) to Tashkent in 1949 led thousands of people to leave the country. It has been estimated that by 1949 over 100,000 people had left Greece for Yugoslavia and the Eastern Block, particularly the USSR and Czechoslovakia. These included tens of thousands of child refugees who had been evacuated by the KKE in an organised campaign.[1][2] The war wrought widespread devastation right across Greece and particularly in the regions of Greek Macedonia and Epirus, causing many people to continue to leave the country even after it had ended.

Greek Civil War

After the invading Axis powers were defeated fighting broke out between the Democratic Army of Greece (DSE) and the Greek Government which had returned from Exile. Many people chose to return their allegiances as to what they regarded as the rightful government of Greece. Soon the Greek Civil War had broken out between the two opposing sides. Many peasants, leftists, socialists, Pontic Greeks, Caucasus Greeks, ethnic minorities from Northern Greece like Macedonians, and ideological communists joined the struggle on the side of the KKE and the DSE. Backing from the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the Socialist People's Republic of Albania helped the Democratic Army of Greece (DSE) to continue their struggle. The DSE recruited heavily amongst the community of Macedonia. It has been estimated that by 1949, from 40 to 60 per cent of the rank and file of the DSE was composed of Macedonians,[3][4] or from 11,000 - 14,000 of the KKE's fighting force.[5] Given their important role in the battle,[6] thand KE changed its policy towards them. At the fifth Plenum of KKE on January 31, 1949, a resolution was passed declaring that after KKE's victory, the Macedonians would find their "national restoration" within a united Greek state.[7] Although they had made a critical contribution to the KKE war effort,[8] their contribution was not enough to turn the tide.

By the spring of 1947 the communist forces controlled much of the Greek rural areas but had yet to achieve significant support in the cities. At the same time, many Greek prisons were full of ELAS Partisans, EAM members and other pro-communist citizens. Thousands of people had been executed by firing squads on claims that they had committed atrocities against the Greek state. After the defeat of DSE in Peloponnese a new wave of terror spread across areas controlled by the Government of Athens. The Provisional Government, with its headquarters on Mount Vitse, soon decided to evacuate all children from the ages of 2 to 14 from all areas controlled by the Provisional Government, most of these children were from Macedonian families. By 1948 the areas controlled by the Provisional Government had been reduced to rural Greek Macedonia and Epirus. Soon many injured partisans and elderly people along with the child refugees had been evacuated to People's Republic of Albania. After 1948 the Yugoslavian Government decided to close the Yugoslav-Greek border, this in turn led many pro-Tito forces in the National Liberation Front to flee to Yugoslavia. Despite this Macedonians continued to fight in the ranks of DSE. By 1948, Macedonians comprised over 30% of the DSE's fighting force according to some estimates,[5] but these estimates have been disputed by the KKE. In the ensuing aftermath, the National Army began to consolidate its control in areas previously controlled by the Provisional Government. Many villages were destroyed in the fighting and the displaced villagers often fled the country through Albania and onto Yugoslavia. One case is the village of Pimenikon (Babčor) in the Kastoria region which was eliminated by US bombers in 1948, displacing hundreds of people.[9] By this time DSE effectively controlled parts of Northern Greece, along with areas of Macedonia where Macedonians represented a clear majority,[10] along with a large tract of Epirus., By the beginning of 1949, increased American aid for the National Army, the Tito-Stalin split, recruiting problems for DSE as well as the major defeat in the islands and in Peloponnese, helped to destabilise the position of DSE.

Many people fled due the collapse of the DSE, it has also been claimed that many Macedonians fled to avoid possible persecution by the advancing National Army.[2][11][12] The Exodus of Macedonians from Greece was the experience of the ethnic Macedonians who left Greece as a result of the Civil War,[13][14] particularly in the Republic of Macedonia and the ethnic Macedonian diaspora. The KKE claims that the total number of political refugees was 55,881,[15] an estimated 28,000 - 32,000 children were evacuated during the Greek Civil War.[2][5][13][16][17] A 1951 document from the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia states that the total number of Macedonians that left Greece during the Civil War was 28,595 [18] whereas some ethnic Macedonian sources put the number of refugees at over 213,000.[19]

Over the course of the war thousands of Communists were killed, imprisoned or had their land confiscated.[2][20] The headquarters of the Democratic Army in Greece reported that from mid-1945 to May 20, 1947, in Western Macedonia alone, 13,259 were tortured, 3,215 were imprisoned and 268 were executed without trial. In the same period 1,891 had been burnt down and 1,553 had been looted and 13,553 people had been resettled by force. Of the many Macedonians who were imprisoned many would often form their own groups within the prisons.[21] It is claimed that the Greek Prison Camps were located on the islands of Ikaria and Makronisos, the Averof jail near Athens and the jails in Thessaloniki and Larisa.

Refugee Children

On March 4, 1948, "Radio Free Greece" announced that all children under the age of 15 would be evacuated from areas under control of the Provisional Government. The older women were instructed to take the children across the border to Yugoslavia and Albania, while the younger women took to the hills with the partisans. Widows of dead partisans soon became surrogate mothers for the children and assisted them in their journey to the Eastern Bloc. Many people also had their children evacuated. By 1948 scores of children had already died from malnutrition, disease and injuries.[10] It is estimated that 8,000 children left the Kastoria area in the ensuing weeks.[9] The children were sorted into groups and made way for the Albanian border. The partisan carers (often young women and men) had to help and support the children as they fled the Civil War.

Thousands of Greek, Bulgarian and Aromanian children were evacuated from the areas under communist control. A United Nations Special Committee on the Balkans (UNSCOB) report confirms that villages with an ethnic Macedonian population were far more willing to let their children be evacuated.[10] They are now known as Децата Бегалци (Decata Begalci) "the Refugee Children" in the Republic of Macedonia and the Slavic ethnic Macedonian diaspora.[22] It is estimated that from 28,000 children to 32,000 children were evacuated in the years 1948 and 1949.[10] According to some sources, the majority of the children sent to the Eastern Bloc had an ethnic Macedonian origin and spoke their native Macedonian language,[10] but this is disputed by official KKE documents and statements made by political refugees in the years after the evacuation.[23][24] Exceptions were made for children under the age of two or three who stayed with their mothers while the rest should be evacuated. Many of these children were spread throughout the Eastern Bloc by 1950 there were 5,132 children in Romania, 4,148 in Czechoslovakia, 3,590 in Poland, 2,859 in Hungary and 672 had been evacuated to Bulgaria.[10]

The official Greek position was that these children had been forcibly taken from their parents by the Communists to be brought up under a socialist system. The abduction of children is referred to by Greek historians and politicians as the Paedomazoma an allusion to the Ottoman Devşirme.

Evacuations following the Communist defeat

By early 1949 the situation for the communists had become dire. The Greek-Yugoslav border was closed and daily groups of refugees were fleeing across the Albanian border. From here they would disperse into the rest of the Eastern Bloc. Many of the partisans did not survive the ensuing journey with many perishing. They were stirred on by the hope of fighting for the Greek Communist Party and the Democratic Army of Greece from other parts of the World. Many others were refugees whose homes and businesses had been destroyed by the civil war fighting. Others still were expelled by the Government forces for their collaboration with the Bulgarian Ohrana during the war. Thousands fled across the border before the Greek government was able to re-established control in former Communist held territory.

Thousands of refugees began to flee across the Eastern Bloc. Many ended up in the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia and across the Eastern Bloc. Thousands more left for Australia, the United States and Canada.[25] This process separated many families permanently with brothers and sisters often separated from each other. It was common for mothers to lose contact with their children and never to see them again.[9] The most visible effect of the Civil War was the mass emigration.[26]

Exile from Greece

In 1947 the legal act L-2 was issued. This meant that all people who had fought against the Greek government during the Greek Civil War and had left Greece would have their citizenship confiscated and were banned from returning to the country. On January 20, 1948 the legal act M was issued which allowed the Greek government to confiscate the property of those who were stripped of their citizenship.[27] This effectively had exiled the defeated KKE and its supporters who had left Greece.

Exodus of Slav-Macedonians from Greece

The Exodus of Slav-Macedonians from Greece[13][14] (Macedonian: Егзодус на Македонци од Грција, Egzodus na Makedonci od Grcija) refers to the thousands of Slav-Macedonians who were evacuated, fled or expelled during the Greek Civil War in the years 1945 to 1949, many of whom fled to avoid persecution.[2][11][12] Although these refugees have been classed as political refugees there have been claims that they were also targeted due to their ethnic and cultural identities. Many Slav-Macedonians had sided with the KKE which in 1934 had expressed its intent to "fight for the national self-determination of the repressed Slav-Macedonians (ethnic group)"[28] and after the KKE passed a resolution at its Fifth Plenum on 31 January 1949 in which "after the KKE victory, the Slav-Macedonians would find their national restoration within a united Greek state".[7] The ethnic Macedonians fought alongside the DSE under their own military wing, the National Liberation Front (Macedonia) (NOF). From its foundation until its merger with the DSE, the NOF had fought alongside the Greek Communist Party. By 1946 thousands of Slav-Macedonians had joined the struggle with NOF, alongside them Aromanians from the Kastoria region were also prominent in the ranks of NOF. Under the NOF, Slav-Macedonian culture was allowed to flourish in Greece. Over 10,000 children went to 87 schools, Macedonian language newspapers were printed and theaters opened. As the Governmental forces approached these facilities were either shut down or destroyed.[29] Many people feared oppression and the loss of their rights under the rule of the Greek government, which in turn caused many people to flee Greece. By 1948, DSE and the Provisional Government, effectively only controlled areas of Northern Greece that Slav-Macedonians villages were also included.

After the Provisional Government in 1948 announced that all children were to leave the DSE controlled areas of Greece many Slav-Macedonians left the war zone. Some sources estimate that tens of thousands of Slav-Macedonians left Greece in the ensuing period. The exodus of Slav-Macedonians from Greek Macedonia continued in the aftermath of the Greek Civil War .[30] Most of the refugees were evacuated to the Eastern Bloc, after which many returned to the Socialist Republic of Macedonia.

Establishment of refugees overseas

After the Communist defeat the majority of communists fled to Albania before making their way to the rest of the Eastern Bloc. The majority of the remaining partisans in the Democratic Army of Greece had been evacuated to Tashkent in the Soviet Union, while others were sent to Poland, Hungary and Romania. A commune of ex-communist partisans had been established in village of Buljkes in Vojvodina, Yugoslavia. It was in Tashkent that the Headquarters of the Greek Communist Party were reestablished. Special preparations were made for the defeated army and accommodation and supplies were readied.

Many of the refugee children were placed in Evacuation camps across Europe. They often ended up in places from Poland, Bulgaria and the Soviet Union. The largest group was to end up in Yugoslavia. Here special evacuation camps and Red Cross field hospitals were set up for the children. Most were placed in the Socialist Republic of Macedonia. Over 2,000 homes were prepared for the children in the Socialist Republic of Macedonia. and many were placed into foster care rather than into orphanages and evacuation camps. Across the Eastern Bloc the refugees were often educated in three and often four languages; Greek, the newly codified Macedonian language, the host countries' language and Russian.

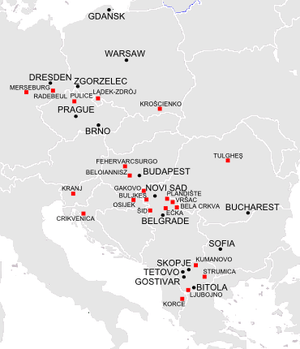

Yugoslavia

Half of all the refugees from the Greek Civil War were sent to Yugoslavia. Many of the early refugees entered Yugoslavia directly while later refugees had to pass through Albania after the border was closed. The majority of the refugees were settled in the Socialist Republic of Macedonia while many were settled in the Socialist Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, where Slav-Macedonians still constitute a minority today. The Yugoslav branch of the Red Cross was able to settle 11,000 children across Yugoslavia. Throughout Yugoslavia room was made in specially designed homes by the Red Cross for the refugees. The ten children's homes held approximately 2,000 children. The remaining 9,000 were placed with families in the Socialist Republic of Macedonia.[10] The largest group of refugees including 25,000 Slav-Macedonians moved to Yugoslavia.[31]

Socialist Republic of Macedonia

Most of the post-World War Two refugees sent to Yugoslavia went to the Socialist Republic of Macedonia. This was for obvious reasons such as the short distance between the borders of Greece and Yugoslavia. Soon the flow of people reversed and many Macedonians from Yugoslavia entered Greece with the hope of aiding the National Liberation Front. The largest group of refugee children from the Greek Civil War was to end up in the People's Republic of Macedonia. Upon crossing the Yugoslav border many children were sent to villages such as Ljubojno and Brajčino before being relocated to larger centres such as Skopje and Bitola. These were joined by thousands more refugees, partisans and expellees until the border with Yugoslavia was closed. From then on refugees had to enter the country via Albania. The majority of these refugee children were Slav-Macedonian speakers, who remain in the Republic of Macedonia to this day.

The refugees from Greek Macedonia were primarily settled in deserted villages and areas across the Republic of Macedonia. A large proportion went to the Tetovo and Gostivar areas. Another large group was to settle in Bitola and the surrounding areas, while refugee camps were established in Kumanovo and Strumica. Large enclaves of refugees and their descendants can be found in the suburbs of Topansko Pole and Avtokomanda in Skopje. They joined mainstream Macedonian society, with most being highly educated. Most have never returned to Greece. The Republic of Macedonia was the centre of Slav-Macedonian refugees from the Greek Civil War. Some estimates put the number of refugees and their descendants at over 50,000 people.[5]

Vojvodina

Vojvodina became the host to one of the largest refugee populations across the Eastern Bloc. In Vojvodina a special ex-German camp was set up for the refugees, Buljkes. Most of these refugees were ELAS members and the so-called "Greek Commune" was established. Although many were Greeks, it is known that a large proportion of the "Greeks" were in fact Slav-Macedonians.[32] The first group of refugees to come to Buljkes was from Kumanovo on May 25, 1945. The group included 1454 refugees, mainly partisans. By June 1945 another group of 2,702 refugees had been transferred to Vojvodina. In the spring of 1946 a group of refugees from Greek Macedonia numbering around 250 people had left the camp.[32] Many more had left the commune for neighbouring villages which left the commune primarily Greek populated. It was here that the Greek newspaper Foni tou Boulkes, was published alongside children's books and the paper of the Communist party of Greece. A primary school was established and the commune began to print its own currency. Eventually the camp was shut down and the villagers were transferred. Other camps were established in Bela Crkva, Plandište, Vršac, Ečka and Šid while the villages of Gakovo and Kruševlje were repopulated by refugees. By 1946 the total population of Buljkes had reached 4,023 people. Of the remaining Slav-Macedonians in Vojvodina at this time many left for the Czechoslovakia or were resettled in the People's Republic of Macedonia.[33]

Eastern Bloc

Wherever the evacuees found themselves across the Eastern bloc, special provisions were made for them. Across the Eastern Bloc the ethnic Macedonian refugees were taught the newly codified Macedonian language and the host country's language; many often learned Russian.[34] A large proportion of the child refugees eventually found foster parents in the host country while many of the others were eventually transported back to Yugoslavia especially from 1955 when Yugoslavia made efforts to attract the child refugees.[27] By the 1970s hundreds of refugees had returned to the Socialist Republic of Macedonia from the Soviet Union. Most notably from the clusters of refugees in Tashkent and Alma Ata. In 1982 the Greek government enabled an Amnesty Law, this caused many "Greeks by genus" to return to Greece in the subsequent period.

Soviet Union

After the collapse of the Democratic Army of Greece thousands of partisans were evacuated to Tashkent and Alma Ata in Central Asia. An estimated 11,980 Partisans were evacuated to the Soviet Union of which 8,573 were males and 3,407 were females. Many of the ethnic Greek partisans remained in the Soviet Union, while most of the ethnic Macedonian partisans would migrate to Yugoslav Macedonia in the 1960s and 1970s. After the amnesty law of 1980 many Greeks returned to Greece, particularly Greek Macedonia.

Poland

Another large group of Refugees of at least 12,300[35] found their way to the Lower Silesia area in Poland. This group included both Greeks and Macedonians.[36] On 25 October a group of Greek refugee children originally sent to Romania were relocated to Poland, a proportion of these found their way to Lądek-Zdrój. Another camp had been established in Krościenko. Facilities in Poland were well staffed and modern with assistance from the Red Cross. Many of these remained in the Lower Silesia area while a large proportion was eventually spread across Southern and Central Poland, soon concentrations of refugees sprung up in Gdańsk and Zgorzelec. Many Greeks decided to return to Greece after the 1982 Amnesty Law allowed their return, whereas a large proportion of Macedonians ended up leaving Poland, for the Socialist Republic of Macedonia. A book about the Macedonian Children in Poland (Macedonian: Македонските деца во Полска) was published in Skopje in 1987. Another book, "The Political refugees from Greece in Poland 1948 - 1975" (Polish: Uchodźcy Polityczni z Grecji w Polsce; 1948 - 1975) has also been published. In 1989 the "Association of Macedonians in Poland" (Polish: Towarzystwo Macedończyków w Polsce, Macedonian: Друштво на Македонците во Полска) was founded in order to lobby the Greek government to allow the free return of civil war refugee children to Greece.

Czechoslovakia

The first refugee children to come to Czechoslovakia were at first quarantined, bathed and placed into an old German camp. Here the refugee children were given food and shelter as they were sorted into age groups. Surrogate mothers from Greek Macedonia were assigned to the younger children while the older children were placed into school. The Czech teachers who were trained in psychology did their best to train the children. In Czechoslovakia they were taught Czech, Greek, Macedonian and Russian. Friction between the Greek and ethnic Macedonian children led to the relocation of the Greek children. Eventually the children were joined by older Partisans and ex-communist members. By 1950 and estimated 4,000 males, 3,475 females and 4,148 children had been evacuated to Czechoslovakia. By 1960 both Greek and Macedonian communities had been established. Unlike in other communist states the majority of the refugees had chosen to remain in Czechoslovakia. Much of the Greek population left in the 1980s to return to Greece. In the early 1990s a branch of the Association of Refugee Children from the Aegean part of Macedonia was founded in the Czech Republic and in Slovakia.[37] The former Greek refugees were recognised as a national minority by the Government of the Czech Republic.

Bulgaria

Although the People's Republic of Bulgaria originally accepted few refugees, government policy changed and the Bulgarian government actively sought ethnically Slav-Macedonians (Bulgarians)|Macedonian]] refugees. It is estimated that approximately 2,500 children were sent to Bulgaria and 3,000 partisans fled there in the closing period of the war. There had been a larger flow of refugees into Bulgarian as the Bulgarian Army pulled out of the Drama-Serres region in 1944. A large proportion of Macedonian speakers emigrated there. The "Slavic Committee" in Sofia (Bulgarian: Славянски Комитет) helped to attract refugees that had settled in other parts of the Eastern Bloc. According to a political report in 1962 the number of political emigrants from Greece numbered at 6,529.[38] Unlike the other countries in the Eastern Bloc there were no specific organisations founded to deal with specific issues relating to the child refugees, this caused many to cooperate with the "Association of Refugee Children from the Aegean part of Macedonia", an association based in the Socialist Republic of Macedonia.[39] Eventually many of these migrants relocated to the Republic of Macedonia with many being integrated into mainstream Bulgarian society.

Romania

A large evacuation camp was established in the Romanian town of Tulgheş. It was here that many of the younger children were reunited with their parents.[9] It is thought that 5,132 children were evacuated to Romania along with 1,981 men and 1,939 women. Of all the children evacuated to the Eastern bloc the largest number were evacuated to Romania. Special provisions were established for the children. They were taught in the Russian, Greek and Macedonian languages along Romanian. Many of the Greek refugee children returned to Greece after the Amnesty Law released in 1982, while the Slav-Macedonian refugee children went on to become an officially recognised minority group.

Hungary

A large group of refugees was also evacuated to the People's Republic of Hungary in the years 1946-1949. This included 2,161 males, 2,233 females and 2,859 children. The first group of approximately 2,000 children was evacuated to Hungary and placed into military barracks. Another group of 1,200 partisans was transferred from Buljkes to Hungary. An initial refugee camp had been established in the Hungarian village of Fehervarcsurgo. Authorities soon split the groups by the village of origin. They were then "adopted" by the Hungarian community. A Greek village was founded in central Hungary and was named Beloiannisz, after the Greek Communist Fighter, Nikos Beloyannis. They were sent across the country but still received support from the Red Cross and an education in Hungarian, Slav-Macedonian, Greek and Russian. Many chose to leave Hungary in search of relatives and family. Others chose to relocate themselves to the Socialist Republic of Macedonia while many ethnic Greeks left returned to Greece after 1982.

German Democratic Republic

It has been estimated that around 1,200 child refugees found their way to East Germany.[34] At the time it was claimed that all of these children were "Greek" but no distinction was made regarding the ethnicity of the children.[34] There were also ethnically Macedonian and Albanian children who had also been sent to the country.[34] Unlike the rest of Eastern Europe the Macedonian language was not taught to the children in Germany, since the majority were Greek Macedonians. Mostly, the Greek children would end up returning to Greece

Refugees in the West

A large proportion of the adults who had left Europe ended up in the United States, Canada and Australia. Thousands would go on to establish themselves in the hope of returning to Europe. The 1950s witnessed the arrival of over 2,000 refugee children in Canada alone.[40] Thousands of refugees had settled themselves in European cities such as London and Paris in the hope of continuing the struggle of the DSE.

Aftermath

The removal of a large proportion of the population from Greek Macedonia dramatically changed the social and political landscape of the region. Depopulation, repatriation, discrimination and repopulation would all become issues to be resolved in the period following the Greek Civil War.

Loss of Citizenship

In 1947 those who had fought the government or who had fled Greece had their citizenship stripped from them. Many of them were barred from re-entering Greece on a permanent or temporary basis. This meant that the exiles and refugees were unable to return to the land of their birth. Many of the refugees remained in Eastern Europe or left for the West. Citizenship was stripped from the evacuees without the fair hearing to an independent tribunal and other internationally accepted protocols for the seizure of citizenship such as legal representation and the opportunity to defend oneself. This process of seizing citizenship had "historically been used against people identifying as ethnic Macedonians".[41] Despite it applying to all citizens regardless of ethnicity. It has been enforced, in all but one case, only against citizens who identified themselves as members of the "Macedonian" minority.[42] Dual citizens who are stripped of Greek citizenship under Article 20 of the citizenship code are sometimes prevented from entering Greece using the passport of their second nationality.[43] Although since 1998 there have been no new reported cases of this occurring.[44]

In 1982 the Greek government enabled an Amnesty Law. Law 400/76 permitted the return and repatriation of the political refugees who had left Greece during the Greek Civil War. However, the ministerial decree stated that those free to return were “all Greeks by genus who during the Civil War of 1946-1949 and because of it have fled abroad as political refugees”. This excluded many people who were not “Greeks by genus” such as the Bulgarians and Macedonians who had fled Greece following the Civil War. Those who identified themselves as something other than “Greek by genus” were not included in the law and were unable to resume their citizenship or property.[45][46]

Depopulation and loss of property

One major effect of the Macedonian exodus from Northern Greece was the effect of depopulation on the region of Greek Macedonia. This was most markedly felt in the Florina, Kastoria, Kozani and Edessa areas where the Communist party was popular and where the largest concentrations of Macedonians could be found. Many of these depopulated and devastated villages and confiscated properties were given to people from outside of the area. Vlachs and Greeks were given property in the resettlement programme conducted by the Greek Government from the period 1952-58.[26] Many properties were confiscated from those persons who had fled the war and had their citizenship subsequently stripped from them.

Law 1540/85 of April 10, 1985 stated that political refugees could regain property taken by the Greek government as long as they were “Greek by genus”. This excluded many people who were not "Greek by genus", namely the Macedonian refugees who claimed that their ethnicity was not Greek.[45][47]

Denial of re-entry to Greece

Many people who had fled the country were also denied visa for re-entry into Greece. The refugees planned on attending weddings, funerals and other events but were denied access to Greece. These measures were even extended to Australian and Canadian citizens, many of whom have been barred from entering Greece.[25][45] There have been claims that exiles who left Greece were prevented from re-entering Greece when other nationals from the Republic of Macedonia had little or no difficulty when entering Greece. The Greek Helsinki Monitor has called on the Greek government to stop using articles of the Citizenship code to deprive, "non-ethnic Greeks", of their citizenship.[48]

Initiatives and Organization

The ex-partisans and refugee children have established organisations and institutions concerning refugee issues and the exodus of Macedonians from Greece and in order to lobby the Greek government to allow their return to Greece and restoration of their Human Rights. There are eight major "Deca Begalci" organisations which have been set up by the Refugee Children and exiled Macedonians.[49] These organisations have traditionally been orientated by the ethnic Macedonia refugees, as most of the ethnic Greek refugees have rejoined mainstream Greek society.

The World Re-Union of Refugee Children

The most notable event organised by the Macedonians refugee children is the Re-union of the refugee children or the World Congress of the Refugee Children. The first World Congress of the Refugee Children was held in July, 1988 in the city of Skopje. The second re-union was held in 1998 and the third was in 2003. The most recent and fourth World Congress of the refugee children from Greek Macedonia began on the 18th of July, 2008. This event gathers child refugees from all over the world. Many participants from Romania, Canada, Poland, the Czech Republic, Australia, the United States and Vojvodina attend the event.

The First International Reunion of Child Refugees of Aegean Macedonia took place in Skopje between 30 June and 3 July. At the reunion the Association of Child Refugees from Greek Macedonia adopted a resolution urging the Greek government to allow Macedonian political refugees who left Greece after the Greek Civil War to return to Greece. In addition a large rally was held in Juna 1988 by the refugees who were forced to leave Greece in 1948. This was repeated again on August 10, 1988, the 75th anniversary of the Partition of Macedonia.[50]

The second world reunion was planned with the help of the Rainbow Party[25] which has been involved in coordinating the event and reuniting many people with relatives which are still living in Greece. The World Reunion of 1998 involved a visit to the Republic of Greece organised by the Aegean Macedonians living in Greece. The World Congress lasted in Skopje from 15 July to the 18th. A historic trip was scheduled for the Greek city of Edessa on the 19th. Although 30 people were barred entry from Greece despite having Canadian citizenship, allegedly due to their Ethnic Macedonian identity and involvement in Macedonian diaspora organisations.[51]

Other groups

The Association of Refugee Children from the Aegean part of Macedonia (ARCAM) was founded by the refugee children in 1979 with the intention of reuniting all the former child refugees living throughout the whole world.[37] It has worked closely with The Association of the Macedonians from the Aegean Part of Macedonia. The organisation's main aims were to lobby the Greek government in returning citizenship and allowing visas for re-entry into Greece by the exiled Refugee Children. The organisation was established in 1979 and helped to organise the first World Reunion held by the refugee's was held in Skopje. Chapters of ARCAM were soon established in Toronto, Adelaide, Perth, Melbourne, Skopje, Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia.[37]

Other groups founded by the Refugee Children include the Association of the Expelled Macedonians “Aegean”, the Association of the Refugee Children - Republic of Macedonia and the Organization of the Macedonian Descendants from the Aegean Part of Macedonia - Bitola.[52]

List of notable refugees

- Georgi Ajanovski (1940 - ) - journalist and children's writer

- Vangel Ajanovski-Oče (1909–1996) - member of the National Liberation Front (Macedonia) and leader of SNOF

- Kostas Axelos (1924-2010 ) - philosopher

- Dimitar Dimitrov (1937 - ) - professor, philosopher, politician and writer

- Charilaos Florakis (1914–2005)- Brigadier General of DSE, General Secretary of KKE since 1970

- Risto Kirjazovski (1927–2008) - historian, scientist and publisher

- Jagnula Kunovska (1943 - ) - jurist, politician and painter from Kastoria

- Paskal Mitrevski (1912–1978) - Former president of the National Liberation Front

- Dimitrios Partsalidis (1905–1980) - Member of the CC oh CPG

- Ljubka Rondova (1936 - ) - folk singer

- Blagoj Shklifov (1935–2003) - phonologist and dialectologist

- Andreas Tsipas (Andreja Čipov) (1904–1956) - communist leader

- Markos Vafiadis (1906–1992) - Military Chief of DSE Supreme HQ, president of the Provisional Government

- Ilios Yannakakis (1931 - ) - historian and politologist, professor emeritus

- Iannis Xenakis (1922-2001) - composer and architect

- Nikolaos Zachariadis (1903–1973) - General secretary of the Greek Communist Party

- Martha (1946 - ) and Tena (1948 - ) Elefteriadu - popular Czech duo singers

See also

- Greek Civil War

- National Liberation Front (Macedonia)

- Macedonians of Greek Macedonia

- Greek Communist Party

- Democratic Army of Greece

References

- ↑ Keith, Brown (2003). The Past in Question: Modern Macedonia and the Uncertainties of Nation. Princeton University Press. p. 271. ISBN 0-691-09995-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Danforth, Loring M. (1997). The Macedonian Conflict. Princeton University Press. p. 54. ISBN 0-691-04356-6.

- ↑ Clogg, Richard. "Catastrophe and occupation and their consequences 1923–1949". A Concise History of Greece (Second ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-521-00479-4. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- ↑ Ζαούσης Αλέξανδρος. Η Τραγική αναμέτρηση, 1945-1949 – Ο μύθος και η αλήθεια (ISBN 9607213432).

- 1 2 3 4 Simpson, Neil (1994). Macedonia Its Disputed History. Victoria: Aristoc Press. p. 91. ISBN 0-646-20462-9.

- ↑ Speech presented by Nikos Zachariadis at the Second Congress of the NOF (National Liberation Front of the ethnic Macedonians from Greek Macedonia), published in Σαράντα Χρόνια του ΚΚΕ 1918-1958, Athens, 1958, p. 575.

- 1 2 KKE Official documents,vol 8

- ↑ "Incompatible Allies: Greek Communism and Macedonian Nationalism in the Civil War in Greece, 1943-1949. Andrew Rossos", The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 69, No. 1 (Mar., 1997) (p. 42)

- 1 2 3 4 Hill, Peter (1989). The Macedonians in Australia. Carlisle: Hesperian Press. p. 32. ISBN 0-85905-142-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Frucht, Richard (2000). Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 599. ISBN 1-57607-800-0.

- 1 2 John S. Koliopoulos. Plundered Loyalties: World War II and Civil War in Greek West Macedonia. Foreword by C. M. Woodhouse. New York: New York University Press. 1999. p. 304. 0814747302

- 1 2 Kalyvas, Stathis N.; Eleni Yannakakis (2006). The Logic of Violence in Civil War. Cambridge University Press. p. 312. ISBN 0-521-85409-1.

- 1 2 3 Macridge, Peter A.; Eleni Yannakakis (1997). Ourselves and Others: The Development of a Greek Macedonian Cultural Identity Since 1912. Berg Publishers. p. 148. ISBN 1-85973-138-4.

- 1 2 Multicultural Canada

- ↑ 3rd KKE congress 10–14 October 1950: Situation and problems of the political refuges in People’s Republics pages 263 - 311 (3η Συνδιάσκεψη του Κόμματος (10–14 October 1950. Βλέπε: "III Συνδιάσκεψη του ΚΚΕ, εισηγήσεις, λόγοι, αποφάσεις - Μόνο για εσωκομματική χρήση - Εισήγηση Β. Μπαρτζιώτα: Η κατάσταση και τα προβλήματα των πολιτικών προσφύγων στις Λαϊκές Δημοκρατίες", σελ. 263 – 311”) Quote: “Total number of political refuges : 55,881 (23,028 men, 14,956 women and 17,596 children, 368 unknown or not accounted)”

- ↑ "Macedonians in Greece". Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ↑ Minahan, James (2000). One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 440. ISBN 0-313-30984-1.

- ↑ report of General consultant of Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia addressed to foreign ministry of Greece Doc 47 15-7-1951 SMIR, ΡΑ, Grcka, 1951, f-30, d-21,410429, (έκθεση του γενικού προξενείου της Γιουγκοσλαβίας στη Θεσσαλονίκη SMIR, ΡΑ, Grcka, 1951, f-30, d-21,410429, Γενικό Προξενείο της Ομόσπονδης Λαϊκής Δημοκρατίας της Γιουγκοσλαβίας προς Υπουργείο Εξωτερικών, Αρ. Εγγρ. 47, Θεσσαλονίκη 15.7.1951. (translated and published by Spiros Sfetas . ΛΓ΄, Θεσσαλονίκη 2001-2002 by the Macedonian Studies ) Quote: “According to the report of General consultant of Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia the total number of Macedonian refugees who came from Greece between the years 1941–1951 is 28,595. From 1941 till 1944 500 found refuge in Yugoslav Macedonia, in 1944 4,000 people, in 1945 5,000 , in 1946 8,000, in 1947 6,000, in 1948 3,000, in 1949 2,000, in 1950 80, and in 1951 15 people. About 4,000 left Yugoslavia and moved to other Socialist countries (and very few went also to western countries). So in 1951 at Yugoslavia were 24,595 refuges from Greek Macedonia. 19,000 lived in Yugoslav Macedonia, 4,000 in Serbia (mainly in Gakovo-Krusevlje) and 1595 in other Yugoslav republics.”

- ↑ Watch 1320 Helsinki, Human Rights Watch/Helsinki (Organization : U.S.); Lois Whitman; Jeri Laber (1994). Denying Ethnic Identity: The Macedonians of Greece. Toronto: Human Rights Watch. p. 6. ISBN 1-56432-132-0.

- ↑ Rossos, Andrew (2007). Macedonia and the Macedonians: A History. Hoover Press. p. 208. ISBN 0-8179-4881-3.

- ↑ Voglis, Polymeris (2002). Becoming a Subject: Political Prisoners During the Greek Civil War. Berghahn Books. p. 204. ISBN 1-57181-308-X.

- ↑ Brown, Keith (2003). The Past in Question: Modern Macedonia and the Uncertainties of Nation. Princeton University Press. p. 271. ISBN 0-691-09995-2.

- ↑ Dimitris Servou, "The Paidomazoma and who is afraid of Truth", 2001

- ↑ Thanasi Mitsopoulou "We brought up as Greeks" ,Θανάση Μητσόπουλου "Μείναμε Έλληνες"

- 1 2 3 Jupp, James (2001). The Australian People: An Encyclopedia of the Nation, Its People and Their Origins. Cambridge University Press. p. 574. ISBN 0-521-80789-1.

- 1 2 Cowan, Jane K. (2000). Macedonia: The Politics of Identity and Difference. Pluto Press. p. 37. ISBN 0-7453-1589-5.

- 1 2 Poulton, Hugh (2000). Who are the Macedonians?. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 167. ISBN 1-85065-534-0.

- ↑ KKE, Πέντε Χρόνια Αγώνες 1931-1936, Athens, 2nd ed., 1946.

- ↑ Shea, John (1997). Macedonia and Greece: The Struggle to Define a New Balkan Nation. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., Publishers. p. 116. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- ↑ Petroff, Lilian (1995). Sojourners and Settlers: The Slav- Macedonian Community in Toronto to 1940. University of Toronto Press. p. 180. ISBN 0-8020-7240-2.

- ↑ Panayi, Panikos (2004). Outsiders: A History of European Minorities. 1991: Continuum International Publishing Group,. p. 127. ISBN 1-85285-179-1.

- 1 2 Association of Social History - The Buljkes Experiment 1945-1949

- ↑ Ristović, Milan (1997) Експеримент Буљкес: «грчка република» у Југославији 1945–1949 [Experiment Buljkes: The "Greek republic" in Yugoslavia 1945-1949]. Годишњак за друштвену историју IV, св. 2–3, стр. 179–201.

- 1 2 3 4 Troebst, Stefan (2004). Evacuation to a Cold Country: Child Refugees from the LPP Greek Civil War in the German Democratic Republic, 1949–1989. Toronto: Carfax Publishing. p. 3.

- ↑ "Przemiany demograficzne społeczności greckiej na Ziemi Lubuskiej w latach 1953-1998". Retrieved 27 October 2015. line feed character in

|title=at position 74 (help) - ↑ Bugajski, Janusz (1993). Ethnic Politics in Eastern Europe: A Guide to Nationality Policies, Organizations, and Parties. Toronto: M.E. Sharpe. p. 359. ISBN 1-56324-282-6.

- 1 2 3 TJ-Hosting. "MHRMI - Macedonian Human Rights Movement International". Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ↑ Marinov, Tchavdar (2004). Aegean Macedonians and the Bulgarian Identity Politics. Oxford: St Antony’s College, Oxford. p. 5.

- ↑ Marinov, Tchavdar (2004). Aegean Macedonians and the Bulgarian Identity Politics. Oxford: St Antony’s College, Oxford. p. 7.

- ↑ Petroff, Lilian; Multicultural History Society of Ontario (1995). Sojourners and Settlers: The Macedonian Community in Toronto to 1940. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 180. ISBN 0-8020-7240-2. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ "Country Report on Human Rights Practices in Greece". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ↑ "Greece". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ↑ "Greece". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ↑ "Greece". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 Watch 1320 Helsinki, Human Rights Watch/Helsinki (Organization : U.S.); Lois Whitman; Jeri Laber (1994). Denying Ethnic Identity: The Macedonians of Greece. Toronto: Human Rights Watch. p. 27. ISBN 1-56432-132-0.

- ↑ Council of Europe- Discriminatory laws against Macedonian political refugees from Greece

- ↑ Council of Europe: Discriminatory laws against Macedonian political refugees from Greece

- ↑ "Press Release". Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ↑ Georgi Donevski Visits the Macedonian Community in Toronto

- ↑ Daskalovski, Židas (1999). Elite Transformation and Democratic Transition in Macedonia and Slovenia, Balkanologie, Vol. III, n° 1. Université de Budapest. pp. Vol. III, juillet 1999, page 20.

- ↑ TJ-Hosting. "MHRMI - Macedonian Human Rights Movement International". Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ↑ "Press Release". Retrieved 27 October 2015.

External links

- Dangerous Citizens Online, the online version of Neni Panourgiá's Dangerous Citizens: The Greek Left and the Terror of the State (ISBN 978-0823229680)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||