The Song of Hiawatha

The Song of Hiawatha is an 1855 epic poem, in trochaic tetrameter, by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, featuring a Native American hero. Longfellow's sources for the legends and ethnography found in his poem were the Ojibwe Chief Kahge-ga-gah-bowh during his visits at Longfellow's home; Black Hawk and other Sac and Fox Indians Longfellow encountered on Boston Common; Algic Researches (1839) and additional writings by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, an ethnographer and United States Indian agent; and Heckewelder's Narratives.[1] In sentiment, scope, overall conception, and many particulars, Longfellow's poem is a work of American Romantic literature, not a representation of Native American oral tradition. Longfellow insisted, "I can give chapter and verse for these legends. Their chief value is that they are Indian legends."[2]

Longfellow had originally planned on following Schoolcraft in calling his hero Manabozho, the name in use at the time among the Ojibwe/Anishinaabe of the south shore of Lake Superior for a figure of their folklore, a trickster-transformer. But in his journal entry for June 28, 1854, he wrote, "Work at 'Manabozho;' or, as I think I shall call it, 'Hiawatha'—that being another name for the same personage."[3] Hiawatha was not "another name for the same personage" (the mistaken identification of the trickster figure was made first by Schoolcraft and compounded by Longfellow), but a probable historical figure associated with the founding of the League of the Iroquois, the Five Nations then located in present-day New York and Pennsylvania.[4] Because of the poem, however, "Hiawatha" became the namesake for towns, schools, trains and a telephone company in the western Great Lakes region, where no Iroquois nations historically resided.[5]

Publication and plot

The poem was published on November 10, 1855, and was an immediate success. In 1857, Longfellow calculated that it had sold 50,000 copies.[6]

Longfellow chose to set The Song of Hiawatha at the Pictured Rocks, one of the locations along the south shore of Lake Superior favored by narrators of the Manabozho stories. The Song presents a legend of Hiawatha and his lover Minnehaha in 22 chapters (and an Introduction). Hiawatha is not introduced until Chapter III.

In Chapter I, Hiawatha's arrival is prophesied by a "mighty" peace-bringing leader named Gitche Manito.

Chapter II tells a legend of how the warrior Mudjekeewis became Father of the Four Winds by slaying the Great Bear of the mountains, Mishe-Mokwa. His son Wabun, the East Wind, falls in love with a maiden whom he turns into the Morning Star, Wabun-Annung. Wabun's brother, Kabibonokka, the North Wind, bringer of autumn and winter, attacks Shingebis, "the diver". Shingebis repels him by burning firewood, and then in a wrestling match. A third brother, Shawondasee, the South Wind, falls in love with a dandelion, mistaking it for a golden-haired maiden.

In Chapter III, in "unremembered ages", a woman named Nokomis falls from the moon. Nokomis gives birth to Wenonah, who grows to be a beautiful young woman. Nokomis warns her not to be seduced by the West Wind (Mudjekeewis) but she does not heed her mother, becomes pregnant and bears Hiawatha.

In the ensuing chapters, Hiawatha has childhood adventures, falls in love with Minnehaha, slays the evil magician Pearl-Feather, invents written language, discovers corn and other episodes. Minnehaha dies in a severe winter.

The poem closes with the approach of a birch canoe to Hiawatha's village, containing "the Priest of Prayer, the Pale-face." Hiawatha welcomes him joyously; and the "Black-Robe chief" brings word of Jesus Christ. Hiawatha and the chiefs accept the Christian message. Hiawatha bids farewell to Nokomis, the warriors, and the young men, giving them this charge: "But my guests I leave behind me/ Listen to their words of wisdom,/ Listen to the truth they tell you." Having endorsed the Christian missionaries, he launches his canoe for the last time westward toward the sunset and departs forever.

The story of Hiawatha was dramatized by Tale Spinners for Children (UAC 11054) with Jordan Malek.

Folkloric and ethnographic critiques

General remarks

Much of the scholarship on The Song of Hiawatha in the twentieth century, dating to the 1920s, has concentrated on its lack of fidelity to Ojibwe ethnography and literary genre rather than the poem as a literary work in its own right. In addition to Longfellow’s own annotations, Stellanova Osborn (and previously F. Broilo in German) tracked down "chapter and verse" for every detail Longfellow took from Schoolcraft.[7] Others have identified words from native languages included in the poem.

Schoolcraft as a "textmaker" seems to have been inconsistent in his pursuit of authenticity, as he justified rewriting and censoring sources.[8] The folklorist Stith Thompson, although crediting Schoolcraft's research with being a "landmark," was quite critical of him: "Unfortunately, the scientific value of his work is marred by the manner in which he has reshaped the stories to fit his own literary taste."[9]

Intentionally epic in scope, The Song of Hiawatha was described by its author as "this Indian Edda". But Thompson judged that despite Longfellow's claimed "chapter and verse" citations, the work "produce[s] a unity the original will not warrant," i.e., it is non-Indian in its totality.[4] Thompson found close parallels in plot between the poem and its sources, with the major exception that Longfellow took legends told about multiple characters and substituted the character "Hiawatha" as the protagonist of them all.[10] Resemblances between the original stories, as "reshaped by Schoolcraft," and the episodes in the poem are but superficial, and Longfellow omits important details essential to Ojibwe narrative construction, characterization, and theme. This is the case even with "Hiawatha’s Fishing," the episode closest to its source.[5] Of course, some important parts of the poem were more or less Longfellow’s invention from fragments or his imagination. "The courtship of Hiawatha and Minnehaha, the least ‘Indian’ of any of the events in ‘Hiawatha,’ has come for many readers to stand as the typical American Indian tale."[11] Also, "in exercising the function of selecting incidents to make an artistic production, Longfellow . . . omitted all that aspect of the Manabozho saga which considers the culture hero as a trickster,"[12] this despite the fact that Schoolcraft had already diligently avoided what he himself called "vulgarisms."[13]

In his book on the development of the image of the Indian in American thought and literature, Pearce wrote about The Song of Hiawatha: "It was Longfellow who fully realized for mid-nineteenth century Americans the possibility of [the] image of the noble savage. He had available to him not only [previous examples of] poems on the Indian . . . but also the general feeling that the Indian belonged nowhere in American life but in dim prehistory. He saw how the mass of Indian legends which Schoolcraft was collecting depicted noble savages out of time, and offered, if treated right, a kind of primitive example of that very progress which had done them in. Thus in Hiawatha he was able, matching legend with a sentimental view of a past far enough away in time to be safe and near enough in space to be appealing, fully to image the Indian as noble savage. For by the time Longfellow wrote Hiawatha, the Indian as a direct opponent of civilization was dead, yet was still heavy on American consciences . . . . The tone of the legend and ballad…would color the noble savage so as to make him blend in with a dim and satisfying past about which readers could have dim and satisfying feelings."[14]

Historical Iroquois Hiawatha

There is virtually no connection, apart from name, between Longfellow's hero and the sixteenth-century Iroquois chief Hiawatha who co-founded the Iroquois League. Longfellow took the name from works by Schoolcraft, which he acknowledged as his main sources. In his notes to the poem, Longfellow cites Schoolcraft as a source for

"a tradition prevalent among the North American Indians, of a personage of miraculous birth, who was sent among them to clear their rivers, forests, and fishing-grounds, and to teach them the arts of peace. He was known among different tribes by the several names of Michabou, Chiabo, Manabozo, Tarenyawagon, and Hiawatha."

Longfellow's notes make no reference to the Iroquois or the Iroquois League or to any historical personage.

However, according to ethnographer Horatio Hale (1817–1896), there was a longstanding confusion between the Iroquois leader Hiawatha and the Iroquois deity Aronhiawagon because of "an accidental similarity in the Onondaga dialect between [their names]." The deity, he says, was variously known as Aronhiawagon, Tearonhiaonagon, Taonhiawagi, or Tahiawagi; the historical Iroquois leader, as Hiawatha, Tayonwatha or Thannawege. Schoolcraft "made confusion worse ... by transferring the hero to a distant region and identifying him with Manabozho, a fantastic divinity of the Ojibways. [Schoolcraft's book] has not in it a single fact or fiction relating either to Hiawatha himself or to the Iroquois deity Aronhiawagon."

In 1856, Schoolcraft published The Myth of Hiawatha and Other Oral Legends Mythologic and Allegoric of the North American Indians, reprinting (with a few changes) stories previously published in his Algic Researches and other works. Schoolcraft dedicated the book to Longfellow, whose work he praised highly.[15]

The U.S. Forest Service has said that both the historical and poetic figures are the sources of the name for the Hiawatha National Forest.[16]

Indian words recorded by Longfellow

Longfellow cites the Indian words he used as from the works by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft. The majority of the words were Ojibwa, with a few from the Dakota, Cree and Onondaga languages.

Though the majority of the Native American words included in the text accurately reflect pronunciation and definitions, some words seem to appear incomplete. For example, the Ojibway words for "blueberry" are miin (plural: miinan) for the berries and miinagaawanzh (plural: miinagaawanzhiig) for the bush upon which the berries grow. Longfellow uses Meenah'ga, which appears to be a partial form for the bush, but he uses the word to mean the berry. Critics believe such mistakes are likely attributable to Schoolcraft (who was often careless about details) or to what always happens when someone who does not understand the nuances of a language and its grammar tries to use select words out of context.[17]

Inspiration from the Finnish Kalevala

The Song of Hiawatha was written in trochaic tetrameter, the same meter as Kalevala, the Finnish epic compiled by Elias Lönnrot from fragments of folk poetry. Longfellow had learned some of the Finnish language while spending a summer in Sweden in 1835.[18] It is likely that, 20 years later, Longfellow had forgotten most of what he had learned of that language, and he referred to a German translation of the Kalevala by Franz Anton Schiefner.[19] Trochee is a rhythm natural to the Finnish language—insofar as all Finnish words are normally accented on the first syllable—to the same extent that iamb is natural to English. Longfellow’s use of trochaic tetrameter for his poem has an artificiality that the Kalevala does not have in its own language.[20]

He was not the first American poet to use the trochaic (or tetrameter) in writing Indian romances.[20] Schoolcraft had written a romantic poem, Alhalla, or the Lord of Talladega (1843) in trochaic tetrameter, about which he commented in his preface:

"The meter is thought to be not ill adapted to the Indian mode of enunciation. Nothing is more characteristic of their harangues and public speeches, than the vehement yet broken and continued strain of utterance, which would be subject to the charge of monotony, were it not varied by the extraordinary compass in the stress of voice, broken by the repetition of high and low accent, and often terminated with an exclamatory vigor, which is sometimes startling. It is not the less in accordance with these traits that nearly every initial syllable of the measure chosen is under accent. This at least may be affirmed, that it imparts a movement to the narrative, which, at the same time that it obviates languor, favors that repetitious rhythm, or pseudo-parallelism, which so strongly marks their highly compound lexicography."[21]

Longfellow wrote to his friend Ferdinand Freiligrath (who had introduced him to Finnische Runen in 1842)[22][23] about the latter's article, "The Measure of Hiawatha" in the prominent London magazine, Athenaeum (December 25, 1855): "Your article . . . needs only one paragraph more to make it complete, and that is the statement that parallelism belongs to Indian poetry as well to Finnish… And this is my justification for adapting it in Hiawatha."[24] Trochaic is not a correct descriptor for Ojibwe oratory, song, or storytelling, but Schoolcraft was writing long before the study of Native American linguistics had come of age. Parallelism is an important part of Ojibwe language artistry.

Cultural response

Reception and influence

In August 1855, The New York Times carried an item on "Longfellow's New Poem", quoting an article from another periodical which said that it "is very original, and has the simplicity and charm of a Saga... it is the very antipodes [sic] of Alfred Lord Tennyson's Maud, which is . . . morbid, irreligious, and painful." In October of that year, the New York Times noted that "Longfellow's Song of Hiawatha is nearly printed, and will soon appear."

By November its column, "Gossip: What has been most Talked About during the Week," observed that "The madness of the hour takes the metrical shape of trochees, everybody writes trochaics, talks trochaics, and think [sic] in trochees: ...

- "By the way, the rise in Erie

- Makes the bears as cross as thunder."

- "Yes sir-ree! And Jacob's losses,

- I've been told, are quite enormous..."

The New York Times review of The Song of Hiawatha was scathing.[25] The anonymous reviewer judged that the poem "is entitled to commendation" for "embalming pleasantly enough the monstrous traditions of an uninteresting, and, one may almost say, a justly exterminated race. As a poem, it deserves no place" because there "is no romance about the Indian." He complains that Hiawatha's deeds of magical strength pall by comparison to the feats of Hercules and to "Finn Mac Cool, that big stupid Celtic mammoth." The reviewer writes that "Grotesque, absurd, and savage as the groundwork is, Mr. LONGFELLOW has woven over it a profuse wreath of his own poetic elegancies." But, he concludes, Hiawatha "will never add to Mr. LONGFELLOW's reputation as a poet."[26]

Thomas Conrad Porter, a professor at Franklin and Marshall College, believed that Longfellow had been inspired by more than the metrics of the Kalevala. He claimed The Song of Hiawatha was "Plagiarism" in the Washington National Intelligencer of November 27, 1855. Longfellow wrote to his friend Charles Sumner a few days later: "As to having 'taken many of the most striking incidents of the Finnish Epic and transferred them to the American Indians'—it is absurd".[19] Longfellow also insisted in his letter to Sumner that, "I know the Kalevala very well, and that some of its legends resemble the Indian stories preserved by Schoolcraft is very true. But the idea of making me responsible for that is too ludicrous."[2] Later scholars continued to debate the extent to which The Song of Hiawatha borrowed its themes, episodes, and outline from the Kalevala.[27]

Despite the critics, the poem was immediately popular with readers and continued so for many decades. The Grolier Club named The Song of Hiawatha the most influential book of 1855.[28] Lydia Sigourney was inspired by the book to write a similar epic poem on Pocahontas, though she never completed it.[29]

Music

Longfellow's poem was taken as the first American epic to be composed of North American materials and free of European literary models. Earlier attempts to write a national epic, such as The Columbiad of Richard Snowden (1753-1825), ‘a poem on the American war’ published in 1795, or Joel Barlow's Vision of Columbus (1787) (rewritten and entitled The Columbiad in 1807), were considered derivative. Longfellow provided something entirely new, a vision of the continent's pre-European civilisation in a metre adapted from a Finnish, non-Indo-European source.

Soon after the poem's publication, composers competed to set it to music. One of the first to tackle the poem was Emile Karst, whose cantata Hiawatha (1858) freely adapted and arranged texts of the poem.[30] It was followed by Robert Stoepel's Hiawatha: An Indian Symphony, a work in 14 movements that combined narration, solo arias, descriptive choruses and programmatic orchestral interludes. The composer consulted with Longfellow, who approved the work before its premiere in 1859, but despite early success it was soon forgotten. [30] An equally ambitious project was the 5-part instrumental symphony by Ellsworth Phelps in 1878.[31]

The poem also influenced two composers of European origin who spent a few years in the USA but did not choose to settle there. The first of these was Frederick Delius, who completed his tone poem Hiawatha in 1888 and inscribed on the title page the passage beginning “Ye who love the haunts of Nature” from near the start of the poem.[32] The work was not performed at the time and the mutilated score was only revised and recorded in 2009.[33] The other and more notorious instance was the poem's connection with Antonín Dvořák's Symphony No. 9, From the New World, (1893). In an article published in the New York Herald on December 15, 1893, he stated that the second movement of his work was a "sketch or study for a later work, either a cantata or opera ... which will be based upon Longfellow's Hiawatha" (with which he was familiar in Czech translation), and that the third movement scherzo was "suggested by the scene at the feast in Hiawatha where the Indians dance".[34] African-American melodies also appeared in the symphony, thanks to his student Harry Burleigh, who used to sing him songs from the plantations which he then noted down. The fact that Burleigh’s grandmother was part Indian has been suggested to explain why Dvorak came to equate or confuse Indian with African American music in his pronouncements to the press.[35]

Among later orchestral treatments of the Hiawatha theme by American composers there was Louis Coerne's 4-part symphonic suite, each section of which was prefaced by a quotation from the poem. This had a Munich premiere in 1893 and a Boston performance in 1894. Dvorac's student Rubin Goldmark followed with a Hiawatha Overturne in 1896 and in 1901 there were performances of Hugo Kaun's symphonic poems "Minnehaha" and "Hiawatha". There were also more settings of Longfellow's words. Arthur Foote's "The Farewell of Hiawatha" (Op.11, 1886) was dedicated to the Apollo Club of Boston, the male voice group that gave its first performance.[36] In 1897 Frederick Russell Burton (1861 — 1909) completed his dramatic cantata Hiawatha.[37] At the same time he wrote "Hiawatha's Death Song", subtitled 'Song of the Ojibways', which set native words followed by an English translation by another writer.[38] Much later, Ojibwe flute music was to influence the 2013 setting of “The death of Minnehaha” for two voices with piano and flute accompaniment by Mary Montgomery Koppel (b.1982).[39]

The most celebrated setting of Longfellow's story was the cantata trilogy, The Song of Hiawatha (1898–1900), by the African-English composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. The first part, "Hiawatha's Wedding Feast" (Op. 30, No. 1),[40] based on cantos 11-12 of the poem, was particularly famous for well over 50 years, receiving thousands of performances in the UK, the USA, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa. Though it slipped from popularity in recent years, revival performances continue.[41] The initial work was followed by two additional oratorios which were equally popular: "The Death of Minnehaha" (Op. 30, No. 2), based on canto 20, and "Hiawatha's Departure" (Op. 30, No. 4), based on cantos 21-2.[42]

More popular settings of the poem followed publication of the poem. The first was Charles Crozat Converse's "The Death of Minnehaha", published in Boston around 1856. The hand colored lithograph on the cover of the printed song, by John Henry Bufford, is now much sought after.[43] The next popular tune, originally titled "Hiawatha (A Summer Idyl)", was not inspired by the poem. It was composed by ‘Neil Moret’ (Charles Daniels) while on the train to Hiawatha, Kansas, in 1901 and was inspired by the rhythm of the wheels on the rails. It was already popular when James O'Dea added lyrics in 1903 and the music was newly subtitled "His Song to Minnehaha". Later treated as a rag, it went on to become a jazz standard.[44] Duke Ellington was later to incorporate treatments of Hiawatha[45] and Minnehaha[46] in his jazz suite The Beautiful Indians (1946-7). Other popular songs have included "Hiawatha’s Melody of Love", by George W. Meyer with words by Alfred Bryan and Artie Mehlinger (1908),[47] and Al Bowlly's "Hiawatha’s Lullaby" (1933).

Modern composers have written works with the Hiawatha theme for young performers. They include the English musician Stanley Wilson's "Hiawatha, 12 Scenes" (1928) for first grade solo piano, based on Longfellow's lines, and Soon Hee Newbold's rhythmic composition for strings in Dorian mode (2003), which is frequently performed by youth orchestras.[48]

Some performers have incorporated excerpts from the poem into their musical work. Johnny Cash used a modified version of "Hiawatha's Vision“ as the opening piece on Johnny Cash Sings the Ballads of the True West (1965).[49] Mike Oldfield used the sections "Hiawatha's Departure" and "The Son of the Evening Star" in the second part of his Incantations album (1978), rearranging some words to conform more to his music. And Laurie Anderson used parts of the poem's third section at the beginning and end of the final piece of her Strange Angels album (1989).

Artistic use

Artists also responded in number to the epic. The earliest pieces of sculpture were by Edmonia Lewis, who had most of her career in Rome. Her father was Haitian and her mother was Native American and African American. The arrow-maker and his daughter, later called The Wooing of Hiawatha, was modelled in 1866 and carved in 1872.[50] By that time she had achieved success with individual heads of Hiawatha and Minnehaha. Carved in Rome, these are now held by the Newark Museum in New Jersey.[51] In 1872 Lewis carved The Marriage of Hiawatha in marble, a work purchased in 2010 by the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts.[52]

Other 19th-century sculptors inspired by the epic were Augustus Saint-Gaudens; his marble statue of the seated Hiawatha (1874) is held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art;[53] Jacob Fjelde created a bronze statue, Hiawatha carrying Minnehaha, for the Columbian Exposition in 1893. It was installed in Minnehaha Park, Minneapolis, in 1912 (illustrated at the head of this article).

In the 20th century Marshall Fredericks created a small bronze Hiawatha (1938), now installed in the Michigan University Centre; a limestone statue (1949), also at the University of Michigan;[54] and a relief installed at the Birmingham Covington School, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan.[55]

Early paintings were by artists who concentrated on authentic American Native subjects. Eastman Johnson's pastel of Minnehaha seated by a stream (1857) was drawn directly from an Objibwe model.[56] The English artist Frances Anne Hopkins travelled in the hunting country of Canada and used her sketches from the trip when she returned to her studio in England in 1870. Her Minnehaha Feeding Birds was painted about 1880. Critics have thought these two artists had a sentimental approach, as did Charles-Émile-Hippolyte Lecomte-Vernet (1821-1900) in his 1871 painting of Minnehaha, making her a native child of the wild.[57] The kinship of the latter is with other kitsch images, like Bufford's cover for "The Death of Minnehaha" (see above) or those of the 1920s calendar painters James Arthur and Rudolph F. Ingerle (1879 – 1950).

American landscape painters referred to the poem to add an epic dimension to their patriotic celebration of the wonders of the national landscape. Albert Bierstadt presented his sunset piece, The Departure of Hiawatha, to Longfellow in 1868 when the poet was in England to receive an honorary degree at the University of Cambridge.[58] Other examples include Thomas Moran's Fiercely the Red Sun Descending, Burned His Way along the Heavens (1875), held by the North Carolina Museum of Art,[59] and the panoramic waterfalls of Hiawatha and Minnehaha on their Honeymoon (1885) by Jerome Thompson (1814 – 1886).[60] Thomas Eakins made of his Hiawatha (c.1874) a visionary statement superimposed on the fading light of the sky.[61]

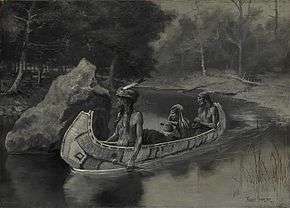

Toward the end of the 19th century, artists deliberately emphasized the epic qualities of the poem, as in William de Leftwich Dodge's Death of Minnehaha (1885). Frederic Remington demonstrated a similar quality in his series of 22 grisailes painted in oil for the 1890 de-luxe photogravure edition of The Song of Hiawatha.[62] One of the editions is owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[63] Dora Wheeler's Minnehaha listening to the waterfall (1884) design for a needle-woven tapestry, made by the Associated Artists for the Cornelius Vanderbilt house, was also epic.[64] The monumental quality survives into the 20th century in Frances Foy's Hiawatha returning with Minnehaha (1937), a mural sponsored during the Depression for the Gibson City Post Office, Illinois.[65]

Parodies

Parodies of the "Song of Hiawatha" emerged immediately on its publication. The New York Times even reviewed one such parody four days before reviewing Longfellow's original poem. This was Pocahontas: or the Gentle Savage, a comic extravaganza which included extracts from an imaginary Viking poem, "burlesquing the recent parodies, good, bad, and indifferent, on The Song of Hiawatha." The Times quoted:

- Whence this song of Pocahontas,

- With its flavor of tobacco,

- And the stincweed [sic] Old Mundungus,

- With the ocho of the Breakdown,

- With its smack of Bourbonwhiskey,

- With the twangle of the Banjo,

- Of the Banjo—the Goatskinner,

- And the Fiddle—the Catgutto...

In 1856 there appeared a 94-page parody, The Song of Milkanwatha: Translated from the Original Feejee. Probably the work of Rev. George A. Strong, it was ascribed on the title page to "Marc Antony Henderson" and to the publishers "Tickell and Grinne". The work following the original chapter by chapter and one passage later became notorious:

- In one hand Peek-Week, the squirrel,

- in the other hand the blow-gun—

- Fearful instrument, the blow-gun;

- And Marcosset and Sumpunkin,

- Kissed him, 'cause he killed the squirrel,

- 'Cause it was a rather big one.

- From the squirrel-skin, Marcosset

- Made some mittens for our hero,

- Mittens with the fur-side inside,

- With the fur-side next his fingers

- So's to keep the hand warm inside;

- That was why she put the fur-side—

- Why she put the fur-side, inside.

Over time, an elaborated version stand-alone version developed, titled "The Modern Hiawatha":

- When he killed the Mudjokivis,

- Of the skin he made him mittens,

- Made them with the fur side inside,

- Made them with the skin side outside.

- He, to get the warm side inside,

- Put the inside skin side outside;

- He, to get the cold side outside,

- Put the warm side fur side inside.

- That's why he put the fur side inside,

- Why he put the skin side outside,

- Why he turned them inside outside.[66]

English composer David. W. Solomons (b.1953) has now set the passage as a canon for 4 equal voices.[67]

In England, Lewis Carroll published Hiawatha's Photographing (1857), which he introduced by noting (in the same rhythm as the Longfellow poem), "In an age of imitation, I can claim no special merit for this slight attempt at doing what is known to be so easy. Any fairly practised writer, with the slightest ear for rhythm, could compose, for hours together, in the easy running metre of The Song of Hiawatha. Having then distinctly stated that I challenge no attention in the following little poem to its merely verbal jingle, I must beg the candid reader to confine his criticism to its treatment of the subject." A poem of some 200 lines, it describes Hiawatha's attempts to photograph the members of a pretentious middle-class family ending in disaster.

- From his shoulder Hiawatha

- Took the camera of rosewood,

- Made of sliding, folding rosewood;

- Neatly put it all together.

- In its case it lay compactly,

- Folded into nearly nothing;

- But he opened out the hinges

- Till it looked all squares and oblongs,

- Like a complicated figure

- In the Second Book of Euclid.[68]

1865 saw the Scottish-born immigrant James Linen's San Francisco (in imitation of Hiawatha).

- Anent oak-wooded Contra Costa,

- Built on hills, stands San Francisco;

- Built on tall piles Oregonian,

- Deeply sunk in mud terraqueous,

- Where the crabs, fat and stupendous,

- Once in all their glory revelled;

- And where other tribes testaceous

- Felt secure in Neptune's kingdom;

- Where sea-sharks, with jaws terrific,

- Fled from land-sharks of the Orient;

- Not far from the great Pacific,

- Snug within the Gate called Golden,

- By the Hill called Telegraph,

- Near the Mission of Dolores,

- Close by the Valley of St. Ann's,

- San Francisco rears its mansions,

- Rears its palaces and churches;

- Built of timber, bricks, and mortar,

- Built on hills and built in valleys,

- Built in Beelzebubbian splendor,

- Stands the city San Francisco.[69]

During World War I, Owen Rutter, a British officer of the Army of the Orient, wrote Tiadatha, describing the city of Salonica, where several hundred thousand soldiers were stationed on the Macedonian Front in 1916-1918:

- Tiadatha thought of Kipling,

- Wondered if he's ever been there

- Thought: "At least in Rue Egnatia

- East and West are met together."

- There were trams and Turkish beggars,

- Mosques and minarets and churches,

- Turkish baths and dirty cafés,

- Picture palaces and kan-kans:

- Daimler cars and Leyland lorries

- Barging into buffalo wagons,

- French and English private soldiers

- Jostling seedy Eastern brigands.[70]

Yet another parody was the work of Mike Shields, (pen name of the British computer scientist F. X. Reid), who composed a computing-oriented parody, "The Song of Hakawatha", containing references to hacking.[71][72]

In the film industry parody was extended to two cartoons with episodes in which inept protagonists are beset by comic calamities while hunting. The connection is made plain by the scenes being introduced by a mock-solemn intonation of lines from the poem. The most famous was the 1937 Silly Symphony Little Hiawatha, whose hero is a small boy whose pants keep falling down.[73] The 1941 Warner Bros. cartoon, Hiawatha's Rabbit Hunt, features Bugs Bunny and a pint-sized version of Hiawatha in quest of rabbit stew.[74]

Notes

- ↑ Longfellow, Henry (1898). The Song of Hiawatha. New York: Hurst and Company. p. v.

- 1 2 Williams 1956, p. 316.

- ↑ Williams 1956, p. 314.

- 1 2 Thompson 1922, p. 129.

- 1 2 Singer 1987.

- ↑ Calhoun 2004, p. 199.

- ↑ Osborn & Osborn 1942, p. 101-293.

- ↑ Clements 1990.

- ↑ Thompson 1966, p. xv.

- ↑ Thompson 1922, p. 128-140.

- ↑ Thompson 1966, p. xv-xvi.

- ↑ Thompson 1922, p. 137.

- ↑ Schoolcraft 1851, p. 585.

- ↑ Pearce 1965, p. 191-192.

- ↑ "One can conclude," wrote Mentor L. Williams, "that Schoolcraft was an opportunist." Williams 1956: 300, note 1

- ↑ "Eastern Region Forest names". United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved February 17, 2012.

- ↑ A comprehensive list, "Native American Words in Longfellow's Hiawatha" has been published at Native Languages.org

- ↑ Calhoun 2004, p. 108.

- 1 2 Irmscher 2006, p. 108.

- 1 2 Schramm 1932.

- ↑ Osborn & Osborn 1942, p. 40.

- ↑ Letter from Freiligrath to Longfellow, in S. Longfellow 1886: 269

- ↑ This book by von Schröter (or von Schroeter) was published originally in 1819. A revised edition was published in 1834. complete texts

- ↑ Williams 1956, p. 302-303.

- ↑ 'The Song of Hiawatha, New York Times, 28 December 1855, p. 2

- ↑ Anonymous, New York Times, 1855 December 28

- ↑ Moyne 1963.

- ↑ Nelson 1981, p. 19.

- ↑ Watts, Emily Stipes. The Poetry of American Women from 1632 to 1945. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 1978: 66–67. ISBN 0-292-76450-2

- 1 2 Pisani 1998.

- ↑ Michael V. Pisani, Imagining Native America in Music, Yale University 2005, p.130

- ↑ From the program notes

- ↑ Parts 1 and 2 are available on YouTube

- ↑ Antonin Dvorak: "The New World" Symphony on YouTube

- ↑ Maurice Peress, Dvorak to Duke Ellington, a Ccnductor explores America's music and its African American roots, Oxford University 2004, pp.23-4

- ↑ George P. Upton, The Standard Cantatas, originally published in 1888, republished in the UK 2010, pp.84-5

- ↑ Burton, Frederick R. (1898). "Hiawatha: A Dramatic Cantata". Oliver Ditson Company. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- ↑ "Hiawatha's Death Song", PDF score for voice and piano accompaniment, MusicaNeo library

- ↑ Composer's programme note; a perfrmance of the work is also available

- ↑ Coleridge-Taylor, S. (1898). Hiawatha's wedding feast: A Cantata for Tenor Solo, Chorus and Orchestra. New York: Novello, Ewer and Co.

- ↑ Coleridge-Taylor - Hiawatha's Wedding Feast on YouTube

- ↑ There is a YouTube performance of "Scenes from the Song Of Hiawatha"

- ↑ Bufford, John Henry. "Sheet Music: The Death of Minnehaha (c.1855)". Authentichistory.com. The Authentic History Center. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- ↑ Neil Moret: Hiawatha, a Summer Idyll on YouTube

- ↑ YouTube

- ↑ YouTube

- ↑ Alfred Bryan, Artie Mehlinger and George W. Meyer (1920). "Hiawatha's Melody Of Love". Halcyon Days. Jerome H. Remick and Co. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- ↑ YouTube

- ↑ Johnny Cash - Hiawatha's Vision & The Road To Kaintuck on YouTube

- ↑ "Old Arrow Maker by Edmonia Lewis". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- ↑ Richardson, Marilyn. "Hiawatha in Rome: Edmonia Lewis and Figures from Longfellow". Antiques & Fine Art Magazine (AntiquesandFineArt.com). Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- ↑ Lewis, Edmonia (1874). "The Marriage of Hiawatha (photo)". artnet.com. Artnet Worldwide Corporation. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- ↑ "Metropolitan Museum of Art Announces Augustus Saint-Gaudens Exhibition". Art Knowledge News. The Art Appreciation Foundation. Retrieved February 23, 2012.

- ↑ Fisher, Marcy Heller. The Outdoor Museum: The magic of Michigan's Marshall M. Fredericks. Wayne State University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-8143-2969-6.

- ↑ "LSA Building Facade Bas Reliefs: Marshall Fredericks". Museum Without Walls. CultureNOW. Retrieved February 23, 2012.

- ↑ Tweed Museum of Art. "Eastman Johnson: Paintings and Drawings of the Lake Superior Ojibwe". Tfaoi.com. Traditional Fine Arts Organization, Inc. Retrieved February 23, 2012.

- ↑ Illustrated in Celia Medonca's ARTECULTURA, Revista Virtual de Artes, com ênfase na pintura, 5 January 2012

- ↑ "Departure of Hiawatha". Maine Memory Network. Maine Historical Society. Retrieved February 23, 2012.

- ↑ "Fiercely the Red Sun Descending, Burned His Way Across the Heavens by Thomas Moran". Museum Syndicate. Jonathan Dunder. Retrieved February 23, 2012.

- ↑ "Hiawatha and Minnehaha on Their Honeymoon by Jerome-Thompson". Art-ist.org. Famous Paintings. Retrieved February 24, 2012.

- ↑ Thomas Eakins, Hiawatha, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

- ↑ A reprint was published as a Nonpareil book in 2005, ISBN 1-56792-258-9; a partial preview is available on Google Books

- ↑ "Hiawatha's Friends Frederic Remington (American, Canton, New York 1861–1909 Ridgefield, Connecticut)". Metmuseum.org. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved February 24, 2012.

- ↑ Candace Wheeler, The Development of Embroidery in America, New York: 1921, pp.133, 138

- ↑ Postal Museum

- ↑ Speak Roughly to your Little Boy: a collection of parodies and burlesques, ed. M.C. Livingston, New York, 1971, p.61

- ↑ Hiawatha or How to make Fur Mittens on YouTube

- ↑ Phantasmagoria and Other Poems, London 1911, first published in 1869, pp.66-7; text online

- ↑ James Linen (1865). The Poetical and Prose Writings of James Linen. W. J. Widdleton., p. 202

- ↑ Cited by M. Mazower, Salonica, City of Ghosts, 2004, p. 313)

- ↑ Reid, F. X. (1989). "The Song Of Hakawatha". Scotland: University of Strathclyde. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ↑ Irmscher, Christoph (2006). Longfellow Redux. University of Illinois Press. pp. 123, 297.

- ↑ View on YouTube

- ↑ View on YouTube

Bibliography

- Calhoun, Charles C. (2004). Longfellow: A Rediscovered Life. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Clements, William M. (1990). "Schoolcraft as Textmaker", Journal of American Folklore 103: 177-190.

- Irmscher, Christoph (2006). Longfellow redux. University of Illinois.

- Longfellow, Samuel, ed (1886). Life of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow; with extracts from his journals and correspondence. Vol. II. Boston: Ticknor and Company.

- Moyne, Ernest John (1963). Hiawatha and Kalevala: A Study of the Relationship between Longfellow's 'Indian Edda' and the Finnish Epic. Folklore Fellows Communications 192. Helsinki: Suomen Tiedeakatemia.

- Nelson, Randy F. (1981). The Almanac of American Letters. Los Altos, California: William Kaufmann, Inc.

- New York Times. 1855 December 28. "Longfellow's Poem": The Song of Hiawatha, Anonymous review.

- Osborn, Chase S.; Osborn, Stellanova (1942). Schoolcraft—Longfellow—Hiawatha. Lancaster, PA: The Jaques Cattell Press.

- Pearce, Roy Harvey (1965). The Savages of America: The Study of the Indian and the Idea of Civilization. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Pisani, Michael V. (1998). "Hiawatha: Longfellow, Robert Stoepel, and an Early Musical Setting of Hiawatha (1859)", American Music, Spring 1998, 16(1): 45–85.

- Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe (1851). Personal Memoirs of a Residence of Thirty Years with the Indian Tribes on the American Frontiers. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo and Co.

- Schramm, Wilbur (1932). "Hiawatha and Its Predecessors", Philological Quarterly 11: 321-343.

- Singer, Eliot A. (1988). ""Paul Bunyan and Hiawatha"". In Dewhurst, C. Kurt; Lockwood, Yvonne R. Michigan Folklife Reader. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press.

- Steil, Mark (2005). Pipestone stages Longfellow's "Hiawatha". Minnesota Public Radio, 2005 July 22.

- Thompson, Stith (1922). "The Indian Legend of Hiawatha, PMLA 37: 128-140

- Thompson, Stith (1966) [1929]. Tales of the North American Indians. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Williams, Mentor L., ed. (1991) [1956]. Schoolcraft's Indian Legends. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Song of Hiawatha. |

- The Song of Hiawatha, complete, at Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/19

-

The Song of Hiawatha public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Song of Hiawatha public domain audiobook at LibriVox

| ||||||||||