Flag of Scotland

| |

| Name | St Andrew's Cross The Saltire |

|---|---|

| Use | National flag |

| Proportion | Not standardised[1] |

| Adopted | 15th century |

| Design | Azure, a saltire Argent. |

The Flag of Scotland, (Scottish Gaelic: Bratach na h-Alba,[2] Scots: Banner o Scotland), also known as St Andrew's Cross or the Saltire, is the national flag of Scotland.[3][4] As the national flag, the Saltire, rather than the Royal Standard of Scotland, is the correct flag for all individuals and corporate bodies to fly.[1] It is also, where possible, flown from Scottish Government buildings every day from 8am until sunset, with certain exceptions.[5]

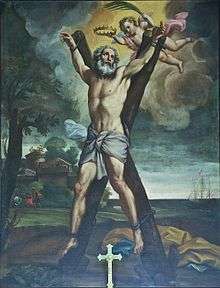

According to legend, the Christian apostle and martyr Saint Andrew, the patron saint of Scotland, was crucified on an X-shaped cross at Patras, (Patrae), in Achaea.[6] Use of the familiar iconography of his martyrdom, showing the apostle bound to an X-shaped cross, first appears in the Kingdom of Scotland in 1180 during the reign of William I. It was again depicted on seals used during the late 13th century, including on one used by the Guardians of Scotland, dated 1286.[6]

Using a simplified symbol which does not depict St. Andrew's image, the saltire or crux decussata, (from the Latin crux, 'cross', and decussis, 'having the shape of the Roman numeral X'), began in the late 14th century. In June 1385, the Parliament of Scotland decreed that Scottish soldiers serving in France would wear a white Saint Andrew's Cross, both in front and behind, for identification.[7]

The earliest reference to the Saint Andrew's Cross as a flag is found in the Vienna Book of Hours, circa 1503, in which a white saltire is depicted with a red background.[7] In the case of Scotland, use of a blue background for the Saint Andrew's Cross is said to date from at least the 15th century,[8] with the first certain illustration of a flag depicting such appearing in Sir David Lyndsay of the Mount's Register of Scottish Arms, circa 1542.[9]

The legend surrounding Scotland's association with the Saint Andrew's Cross was related by Walter Bower and George Buchanan, who claimed that the flag originated in a 9th-century battle, where Óengus II led a combined force of Picts and Scots to victory over the Angles, led by Æthelstan.[6] Supposedly, a miraculous white saltire appeared in the blue sky and Óengus' troops were roused to victory by the omen.[10] Consisting of a blue background over which is placed a white representation of an X-shaped cross, the Saltire is one of Scotland's most recognisable symbols.[11]

Design

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

The heraldic term for an X-shaped cross is a 'saltire', from the old French word saultoir or salteur (itself derived from the Latin saltatorium), a word for both a type of stile constructed from two cross pieces and a type of cross-shaped stirrup-cord.[12] In heraldic language, it may be blazoned azure, a saltire argent. The tincture of the Saltire can appear as either silver (argent) or white, however the term azure does not refer to a particular shade of blue.[13]

Throughout the history of fabric production natural dyes have been used to apply a form of colour,[14] with dyes from plants, including indigo from Woad, having dozens of compounds whose proportions may vary according to soil type and climate; therefore giving rise to variations in shade.[15] In the case of the Saltire, variations in shades of blue have resulted in the background of the flag ranging from sky blue to navy blue. When incorporated as part of the Union Flag during the 17th century, the dark blue applied to Union Flags destined for maritime use was possibly selected on the basis of the durability of darker dyes,[16] with this dark blue shade eventually becoming standard on Union Flags both at sea and on land. Some flag manufacturers selected the same navy blue colour trend of the Union Flag for the Saltire itself, leading to a variety of shades of blue being depicted on the flag of Scotland.[17]

These variations in shade eventually led to calls to standardise the colour of Scotland's national flag,[18] and in 2003 a committee of the Scottish Parliament met to examine a petition that the Scottish Executive adopt the Pantone 300 colour as a standard. (Note that this blue is of a lighter shade than the Pantone 280 of the Union Flag). Having taken advice from a number of sources, including the office of the Lord Lyon King of Arms, the committee recommended that the optimum shade of blue for the Saltire be Pantone 300.[19] Recent versions of the Saltire have therefore largely converged on this official recommendation. (Pantone 300 is #0065BD as hexadecimal web colours.)[20][21][22]

The flag proportions are not fixed, however the Lord Lyon King of Arms states that 5:4 is suitable.[1] (Flag manufacturers themselves may adopt alternative ratios, including 1:2 or 2:3).[23] The ratio of the width of the bars of the saltire in relation to the width of the field is specified in heraldry in relation to shield width rather than flag width. However, this ratio, though not rigid, is specified as one-third to one-fifth of the width of the field.[24]

History

According to legend, in 832 A.D. Óengus II led an army of Picts and Scots into battle against the Angles, led by Æthelstan, near modern-day Athelstaneford, East Lothian. The legend states that whilst engaged in prayer on the eve of battle, Óengus vowed that if granted victory he would appoint Saint Andrew as the Patron Saint of Scotland; Andrew then appeared to Óengus that night in a dream and assured him of victory. On the morning of battle white clouds forming the shape of an X were said to have appeared in the sky. Óengus and his combined force, emboldened by this apparent divine intervention, took to the field and despite being inferior in terms of numbers were victorious. Having interpreted the cloud phenomenon as representing the crux decussata upon which Saint Andrew was crucified, Óengus honoured his pre-battle pledge and duly appointed Saint Andrew as the Patron Saint of Scotland. The white saltire set against a celestial blue background is said to have been adopted as the design of the flag of Scotland on the basis of this legend.[7]

Although the earliest use as a national symbol can be traced to the seal of the Guardians of Scotland in 1286,[25] material evidence for the Saltire being used as a flag, as opposed to appearing on another object such as a seal, brooch or surcoat, dates from somewhat later. The huge heraldic standard of the Great Michael had the "Sanct Androis cors" on a blue background in the Hoist[26] and by 1542 a white saltire set against a blue background was depicted as being the flag of Scotland.[9] An even earlier example known as the "Blue Blanket of the Trades of Edinburgh", reputedly made by Queen Margaret, wife of James III (1451–1488), also shows a white saltire on a blue field.[7] However, in this case the saltire is not the only emblem to be portrayed.

Protocol

Use by the Scottish Government

The Scottish Government has ruled that the Saltire should, where possible, fly on all its buildings every day from 8am until sunset.[5] An exception is made for United Kingdom "national days", when on buildings where only one flagpole is present the Saltire shall be lowered and replaced with the Union Flag.[27] Such flag days are standard throughout the United Kingdom, with the exception of Merchant Navy Day, (3 September), which is a specific flag day in Scotland during which the Red Ensign of the Merchant Navy may be flown on land in place of either the Saltire or Union Flag.[5]

A further Scottish distinction from the UK flag days is that on Saint Andrew's Day, (30 November), the Union Flag will only be flown where a building has more than one flagpole; the Saltire will not be lowered to make way for the Union Flag where a single flagpole is present.[5] If there are two or more flagpoles present, the Saltire may be flown in addition to the Union Flag but not in a superior position.[27] This distinction arose after Members of the Scottish Parliament complained that Scotland was the only country in the world where the potential existed for the citizens of a country to be unable to fly their national flag on their country's national day.[28] (In recent years, embassies of the United Kingdom have also flown the Saltire to mark St Andrew's Day).[29] Many bodies of the Scottish Government use the flag as a design basis for their logo; for example, Safer Scotland's emblem depicts a lighthouse shining beams in a saltire shape onto a blue sky.[30] Other Scottish bodies, both private and public, have also used the saltire in similar ways.[31]

Use by military institutions on land

The seven British Army Infantry battalions of the Scottish Division, plus the Scots Guards and Royal Scots Dragoon Guards regiments, use the Saltire in a variety of forms. Combat and transport vehicles of these Army units may be adorned with a small, (130x80mm approx.), representation of the Saltire; such decals being displayed on the front and/or rear of the vehicle. (On tanks these may also be displayed on the vehicle turret).[32] In Iraq, during both Operation Granby and the subsequent Operation Telic, the Saltire was seen to be flown from the communications whip antenna of vehicles belonging to these units.[33][34] Funerals, conducted with full military honours, of casualties of these operations in Iraq, (plus those killed in operations in Afghanistan),[35] have also been seen to include the Saltire; the flag being draped over the coffin of the deceased on such occasions.[36]

In the battle for "hearts and minds" in Iraq, the Saltire was again used by the British Army as a means of distinguishing troops belonging to Scottish regiments from other coalition forces, in the hope of fostering better relations with the civilian population in the area south west of Baghdad. Leaflets were distributed to Iraqi civilians, by members of the Black Watch, depicting troops and vehicles set against a backdrop of the Saltire.[37]

Immediately prior to, and following, the merger in March 2006 of Scotland's historic infantry regiments to form a single Royal Regiment of Scotland, a multi-million-pound advertising campaign was launched in Scotland in an attempt to attract recruits to join the reorganised and simultaneously rebranded "Scottish Infantry". The recruitment campaign employed the Saltire in the form of a logo; the words "Scottish Infantry. Forward As One." being placed next to a stylised image of the Saltire. For the duration of the campaign, this logo was used in conjunction with the traditional Army recruiting logo; the words "Army. Be The Best." being placed beneath a stylised representation of the Union Flag.[38] Despite this multi-media campaign having had mixed results in terms of overall success,[39] the Saltire continues to appear on a variety of Army recruiting media used in Scotland.

Other uses of the Saltire by the Army include the cap badge design of the Royal Regiment of Scotland, which consists of a (silver) Saltire, surmounted by a (gilt) lion rampant and ensigned with a representation of the Crown of Scotland. (This same design, save for the Crown, is used on both the Regimental flag and tactical recognition flash of the Royal Regiment of Scotland).[40] The badge of the No. 679 (The Duke of Connaught's) Squadron Army Air Corps bears a Saltire between two wreaths ensigned 'Scottish Horse'; an honour they received in 1971 which originated through their links with the Royal Artillery.[41] The Officer Training Corps units attached to universities in Edinburgh and Glasgow, plus the Tayforth University OTC, all feature the Saltire in their cap badge designs.[42]

The Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy adorned three of their aircraft with the Saltire. Specifically, the Westland Sea King Mk5 aircraft of HMS Gannet, operating in the Search and Rescue (SAR) role from Royal Naval Air Station Prestwick, Ayrshire, displayed a Saltire decal on the nose of each aircraft.[43] (The SAR function was transferred from the Royal Navy to Bristow Helicopters, acting on behalf of HM Coastguard, part of the UK's Maritime and Coastguard Agency, with effect from 1 January 2016.)[44]

Although not represented in the form of a flag, the No. 602 (City of Glasgow) Squadron of the Royal Auxiliary Air Force uses the Saltire surmounted by a lion rampant as the device shown on the squadron crest.[45] The station crest of the former RAF Leuchars, Fife, also showed the Saltire, in this case surmounted by a sword. The crest of the former RAF East Fortune, East Lothian, also showed a sword surmounting the Saltire, however unlike Leuchars this sword was shown inverted,[46] and the station crest of the former RAF Turnhouse, Edinburgh, showed a Saltire surmounted by an eagle's head.[47] The East of Scotland Universities Air Squadron crest features a Saltire surmounted by an open book; the book itself being supported by red lions rampant.[48]

General use

In Scotland, planning permission to fly the Saltire from a flagpole is required,[49] therefore it can not be flown at any time by any individual, company, local authority, hospital or school without first obtaining planning permission (in practice this is not enforced). This is not the case in England & Wales where the Saltire can be flown without planning permission first being obtained.[1][5] Many local authorities in Scotland fly the Saltire from Council Buildings, however in 2007 Angus Council approved a proposal to replace the Saltire on Council Buildings with a new Angus flag, based on the council's coat of arms. This move led to public outcry across Scotland with more than 7,000 people signing a petition opposing the council's move, leading to a compromise whereby the Angus flag would not replace but be flown alongside the Saltire on council buildings.[50]

In the United Kingdom, owners of vehicles registered in Great Britain have the option of displaying the Saltire on the vehicle registration plate, in conjunction with the letters "SCO" or alternatively the word "Scotland".[51] In 1999, the Royal Mail issued a series of pictorial stamps for Scotland, with the '2nd' value stamp depicting the Flag of Scotland.[52] In Northern Ireland, sections of the Protestant community routinely employ the Saltire as a means of demonstrating and celebrating their Ulster-Scots heritage.[53]

Use of the Saltire at sea as a Jack or courtesy flag has been observed, including as a Jack on the Scottish Government's Marine Partrol Vessel (MPV) Jura.[54] The ferry operator Caledonian MacBrayne routinely flies the Saltire as a Jack on vessels which have a bow staff, including when such vessels are underway.[55] This practice has also been observed on the Paddle Steamer Waverley when operating in and around the Firth of Clyde.[56] The practice of maritime vessels adopting the Saltire, for use as a jack or courtesy flag, may lead to possible confusion in that the Saltire closely resembles the maritime signal flag M, "MIKE", which is used to indicate "My vessel is stopped; making no way."[57] Obviously mariners who understand this signal code also understand that the saltire is displayed on the jackstaff and not as a signal. For the benefit of Scottish seafarers wishing to display a Scottish flag other than the Saltire, thereby avoiding confusion and a possible fine, a campaign was launched in November 2007 seeking official recognition for the historic Scottish Red Ensign.[58] Despite having last been used officially by the pre-Union Royal Scots Navy and merchant marine fleets in the 18th century,[59] the flag continues to be produced by flag manufacturers[60][61] and its unofficial use by private citizens on water has been observed.[62]

Incorporation into the Union Flag

The Saltire is one of the key components of the Union Flag[63] which, since its creation in 1606, has appeared in various forms[64] following the Flag of Scotland and Flag of England first being merged to mark the Union of the Crowns.[65] (The Union of the Crowns having occurred three years earlier, in 1603, when James VI, King of Scots, acceded to the thrones of both England and Ireland upon the death of Elizabeth I of England). The proclamation by King James, made on 12 April 1606, which led to the creation of the Union Flag states:

By the King: Whereas, some differences hath arisen between Our subjects of South and North Britaine travelling by Seas, about the bearing of their Flagges: For the avoiding of all contentions hereafter. We have, with the advice of our Council, ordered: That from henceforth all our Subjects of this Isle and Kingdome of Great Britaine, and all our members thereof, shall beare in their main-toppe the Red Crosse, commonly called St. George’s Crosse, and the White Crosse, commonly called St. Andrew’s Crosse, joyned together according to the forme made by our heralds, and sent by Us to our Admerall to be published to our Subjects: and in their fore-toppe our Subjects of South Britaine shall weare the Red Crosse onely as they were wont, and our Subjects of North Britaine in their fore-toppe the White Crosse onely as they were accustomed. – 1606.— Proclamation of James VI, King of Scots: Orders in Council – 12 April 1606.[66]

However, in objecting strongly to the form and pattern of Union Flag adopted by James' heralds, whereby the cross of Saint George surmounted that of Saint Andrew, (regarded in Scotland as a slight upon the Scottish nation), a great number of shipmasters and ship-owners in Scotland took up the matter with John Erskine, 18th Earl of Mar, and encouraged him to send a letter of complaint, dated 7 August 1606, to James VI, via the Privy Council of Scotland, stating:

Most sacred Soverayne. A greate nomber of the maisteris and awnaris of the schippis of this your Majesteis kingdome hes verie havelie compleint to your Majesteis Counsell that the form and patrone of the flaggis of schippis, send doun heir and commandit to be ressavit and used be the subjectis of boith kingdomes, is very prejudiciall to the fredome and dignitie of this Estate and will gif occasioun of reprotche to this natioun quhairevir the said flage sal happin to be worne beyond sea becaus, as your sacred majestie may persave, the Scottis Croce, callit Sanctandrois Croce is twyse divydit, and the Inglishe Croce, callit Sanct George, haldin haill and drawne through the Scottis Croce, whiche is thairby obscurit and no takin nor merk to be seen of the Scottis Armes. This will breid some heit and miscontentment betwix your Majesteis subjectis, and it is to be ferit that some inconvenientis sall fall out betwix thame, for oure seyfairing men cannot be inducit to ressave that flag as it is set doun. They haif drawne two new drauchtis and patronis as most indifferent for boith kingdomes which they present to the Counsell, and craved our approbatioun of the same; bot we haif reserved that to you Majesteis princelie determination.— Letter from the Privy Council of Scotland to James VI, King of Scots – 7 August 1606.[67]

Despite the drawings described in this letter as showing drafts of the two new patterns, together with any royal response to the complaint which may have accompanied them, having been lost, (possibly in the 1834 Burning of Parliament), other evidence exists, at least on paper, of a Scottish variant whereby the Scottish cross appears uppermost. Whilst, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, this design is considered by most vexillologists to have been unofficial, there is reason to believe that such flags were employed during the 17th century for use on Scottish vessels at sea.[69][70][71] This flag's design is also described in the 1704 edition of The Present State of the Universe by John Beaumont, Junior, which contains as an appendix The Ensigns, Colours or Flags of the Ships at Sea: Belonging to The several Princes and States in the World.[72]

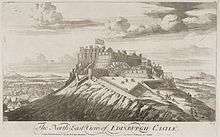

On land, evidence suggesting use of this flag appears in the depiction of Edinburgh Castle by John Slezer, in his series of engravings entitled Theatrum Scotiae, c. 1693. Appearing in later editions of Theatrum Scotiae, the North East View of Edinburgh Castle engraving depicts the Scotch (to use the appropriate adjective of that period) version of the Union Flag flying from the Castle Clock Tower.[73][74] A reduced view of this engraving, with the flag similarly detailed, also appears on the Plan of Edenburgh, Exactly Done.[75] However, on the engraving entitled North Prospect of the City of Edenburgh the detail of the flag, when compared to the aforementioned engravings, appears indistinct and lacks any element resembling a saltire.[76] (The reduced version of the North Prospect ..., as shown on the Plan of Edenburgh, Exactly Done, does however display the undivided arm of a saltire and is thereby suggestive of the Scottish variant).[75]

On 17 April 1707, just two weeks prior to the Acts of Union coming into effect, Sir Henry St George, Garter King of Arms, presented several designs to Queen Anne and her Privy Council for consideration as the flag of the soon to be unified Kingdom of Great Britain. At the request of the Scots representatives, the designs for consideration included that version of Union Flag showing the Cross of Saint Andrew uppermost; identified as being the "Scots union flagg as said to be used by the Scots".[77] However, Queen Anne and her Privy Council approved Sir Henry's original effort, (pattern "one"), showing the Cross of Saint George uppermost.[77]

From 1801, in order to symbolise the union of the Kingdom of Great Britain with the Kingdom of Ireland a new design, which included the St Patrick's Cross, was adopted for the flag of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.[78] A manuscript compiled from 1785 by William Fox, and in possession of the Flag Research Center, includes a full plate showing "the scoth [sic] union" flag with the addition of the cross of St. Patrick. This could imply that there was still some insistence on a Scottish variant after 1801.[79]

Despite its unofficial and historic status the Scottish Union Flag continues to be produced by flag manufacturers,[80] and its unofficial use by private citizens on land has been observed.[81] In 2006 historian David R. Ross called for Scotland to once again adopt this design in order to "reflect separate national identities across the UK",[82] however the 1801 design of Union Flag remains the official flag of the entire United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.[83]

-

Scottish Union Flag. An unofficial variant used in the Kingdom of Scotland during the 17th century, following the Union of the Crowns.

-

.jpg)

Union Flag used in the Kingdom of England from 1606 and, following the Acts of Union, the flag of the Kingdom of Great Britain from 1707–1800.

-

Union Flag since 1801, including the Cross of Saint Patrick, following the Act of Union between the Kingdom of Great Britain and Kingdom of Ireland.

-

Flag of the United Kingdom, (Union Flag since 1801), flying alongside the Flag of England; the Cross of Saint George.

Similar flags

Several flags outside of the United Kingdom are based on the Scottish saltire. In Canada, an inverse representation of the flag (i.e. a blue saltire on a white field), combined with the shield from the royal arms of the Kingdom of Scotland, forms the modern flag of the province of Nova Scotia. Nova Scotia (Latin for "New Scotland") was the first colonial venture of the Kingdom of Scotland in the Americas.[84]

The Dutch municipality of Sint-Oedenrode, named after the Scottish princess Saint Oda, uses a version of the flag of Scotland, defaced with a gold castle having on both sides a battlement.[85]

The flag of Tenerife, an island of the Canary Islands, is identical to the Scottish flag except for the shade of blue. Although some theories claim a connection between the flags, their similarity is likely coincidental.

-

Flag of the Scottish Australian Heritage Council, Australia

-

Regimental flag of the Royal Regiment of Scotland

-

Unofficial design; popular with members of the Tartan Army

-

Provincial flag of Nova Scotia, Canada

-

Flag of Sint-Oedenrode, Netherlands

-

Flag of Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain

-

International Code of Signals flag "M" (Mike)

Royal Standard of Scotland

The Royal Standard of Scotland, also known as the Banner of the King of Scots[86] or more commonly the Lion Rampant of Scotland,[87] is the Scottish Royal Banner of Arms.[88] Used historically by the King of Scots, the Royal Standard of Scotland differs from Scotland's national flag, The Saltire, in that its correct use is restricted by an Act of the Parliament of Scotland to only a few Great Officers of State who officially represent The Sovereign in Scotland.[88] It is also used in an official capacity at Royal residences in Scotland when The Sovereign is not present.[89]

Gallery

-

The Flag of the United Kingdom, Flag of Scotland and Flag of Europe at the Scottish Parliament Building.

-

The Scottish Red Ensign at a historical reenactment of the Battle for Grolle.

-

A variety of Saltires at Murrayfield Stadium; the national stadium of Rugby Union in Scotland.

-

The Flag(s) of Scotland marking the Anglo-Scottish Border.

-

The Flag of Scotland and Flag of Canada at the Canmore Highland Games.

-

The Flag of Scotland seating design at Hampden Park Stadium; the national stadium of Football in Scotland.

-

A replica 17th-century Covenanters' flag.

-

A defaced Saltire belonging to the Bass Rock golf club, North Berwick.

-

The defaced Saltire of the Royal Burgh of Selkirk leading the Common Riding.

-

The Flag of Scotland; Proportions: 2:3.

-

The Flag of Scotland; Proportions: 1:2.

See also

- Bearer of the National Flag of Scotland

- Cross of Burgundy flag

- Flag of Tenerife

- Flags of Europe

- International Code of Signals (letter M)

- List of British flags

- List of Scottish flags

- Royal coat of arms of Scotland

- Saint Patrick's Flag

References

- 1 2 3 4 "The Saltire". The Court of the Lord Lyon. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- ↑ "Visit Athelstaneford. Birthplace of Scotland's Flag" (PDF). Scottish Flag Trust. n.d. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 2010-03-12.

- ↑ Williams, Kevin; Walpole, Jennifer (2008-06-03). "The Union Flag and Flags of the United Kingdom" (PDF). SN/PC/04447. House of Commons Library. Retrieved 2010-02-10.

- ↑ Gardiner, James. "Scotland's National Flag, the Saltire or St Andrews Cross". Scran. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Flag Flying Guidance". Issue No. 13 (Valid from January 2009). The Government of Scotland. 2009-01-01. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- 1 2 3 "Feature: Saint Andrew seals Scotland's independence". The National Archives of Scotland. 2007-11-28. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- 1 2 3 4 Bartram, Graham (2001). "The Story of Scotland's Flags" (PDF). Proceedings of The XIX The XIX International Congress of Vexillology. York, United Kingdom: Fédération internationale des associations vexillologiques. pp. 167–172.

- ↑ Bartram, Graham (2004). British Flags & Emblems. Tuckwell Press. p. 10. ISBN 1-86232-297-X.

The blue background dates back to at least the 15th century.

www.flaginstitute.org - 1 2 National Library of Scotland (1542). "Plate from the Lindsay Armorial". Scran. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- ↑ "National Pride - Scotlandnow - Global Friends of Scotland". Friendsofscotland.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 2012-05-23.

- ↑ "'Super regiment' badge under fire". BBC News (British Broadcasting Corporation). 2005-08-16. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, Second edition, 1989

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions". College of Arms. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- ↑ Holland, Stephanie (1987). All about fabrics: an introduction to needlecraft. Oxford University Press. p. 31. ISBN 0-19-832755-2.

Throughout the history of fabric production, natural dyes have been used. They came from plant and animal sources, usually relating to the area in which the fabric was produced.

Google Books - ↑ "Natural Dyes vs. synthetic dyes". Natural Dyes. WildColours. October 2006. Retrieved 2010-09-28.

- ↑ "Colour of the flag". Flags of the World. Retrieved 2009-12-12.

- ↑ Macdonell, Hamish (2003-02-19). "Parliament to set standard colour for Saltire". The Scotsman (Johnston Press Digital Publishing). Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- ↑ Macdonell, Hamish (2002-06-03). "MSPs are feeling blue over shady Saltire business". The Scotsman (Johnston Press Digital Publishing). Retrieved 2009-11-28.

- ↑ MacQueen, Hector; Wortley, Scott (2000-07-29). "(208) Pantone 300 and the Saltire". Scots Law News (The University of Edinburgh, School of Law.). Archived from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- ↑ "Pantone 300 Coated". Find a PANTONE color. Pantone LLC. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- ↑ BBC News (19 February 2003). "Flag colour is azure thing: Politicians have finally nailed their colours to the mast by specifying the precise shade of blue in Scotland's national flag". BBC News. United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland: British Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 1 November 2003. Retrieved 1 November 2003.

- ↑ "Petition PE512". Public Petitions Committee - Petition PE512 Detail Page. Scotland, United Kingdom: The Scottish Parliament. 2003. Archived from the original on 6 May 2004. Retrieved 6 May 2004.

Tuesday, February 18, 2003: The Education, Culture and Sport Committee considered a petition from Mr George Reid on the Saltire flag. The Committee agreed that the colour of the Saltire flag should be colour reference Pantone 300.

- ↑ "Scotland - St Andrews Saltire)". UK Flags. Flying Colours Flagmakers. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ↑ Fearn, Jacqueline (2008). Discovering Heraldry. Osprey Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 0-7478-0660-8.

The proportions of the ordinaries and diminutives to the shield have been defined but are not rigid and are secondary to good heraldic design. Thus the chief, fess and pale occupy up to one third of the shield, as do the bend, saltire and cross, unless uncharged, when they occupy one fifth, together with the bar and chevron.

Google Books - ↑ "UK Flag Registry". Flag Institute. Retrieved 2009-12-12.

- ↑ Balfour Paul, Sir James (1902). Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland. Vol. iv. A.D. 1507-1513. H.M. General Register House, Edinburgh. p. 477.

- 1 2 "Dates for Hoisting Flags on UK Government Buildings 2009". Flying the Flag on UK Government Buildings. Department for Culture, Media and Sport. 2008-12-16. Archived from the original on 16 March 2009. Retrieved 2009-12-14.

- ↑ "Ministers agree flag day review". BBC News. 2002-05-20. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

- ↑ "St Andrews Day celebrations". The Scottish Executive. 2006-11-07. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- ↑ "Community Safety in Scotland - Information for Practitioners". Law, Order & Public Safety. The Government of Scotland. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- ↑ "The Flag of Scotland" (PDF). FactTheFlag. The Scottish Flag Trust. Retrieved 2009-12-18.

- ↑ "MoD image". MoD. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- ↑ "MoD image". MoD. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- ↑ "MoD image". MoD. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- ↑ "The coffin of Black Watch soldier Kevin Elliot is carried from St Mary's Church on September 15, 2009 in Dundee, Scotland.". trackpads.com. Retrieved 2012-01-09.

- ↑ "Funeral Of Black Watch Bomb Victim". sky.com. Retrieved 2012-01-09.

- ↑ "Operation Iraqi Freedom". Psywarrior.com. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- ↑ "Scottish Infantry, forward as one.". MoD (Shown on liveleak.com). Retrieved 2009-12-02. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ Bruce, Ian (2007-09-19). "Recruits down 15% as Army severs local links". The Herald (Herald & Times Group). Retrieved 2009-06-01.

- ↑ "MoD image". MoD. Archived from the original on 6 August 2009. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- ↑ "MoD web page". MOD. Archived from the original on 26 November 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-03.

- ↑ "MoD web page". MOD. Retrieved 2011-09-13.

- ↑ "MoD web page". MOD. Archived from the original on 27 October 2010. Retrieved 2011-09-13.

- ↑ "Civilian team replaces HMS Gannet search and rescue at Prestwick". BBC News. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- ↑ "602sqn image". The BS Historian. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- ↑ "RAF Stations - E". Air of Authority - A History of RAF Organisation. Retrieved 2010-12-01.

- ↑ "RAF Stations - T". Air of Authority - A History of RAF Organisation. Retrieved 2010-12-01.

- ↑ "East of Scotland Universities Air Sqn". MOD. Retrieved 2011-09-13.

- ↑ Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997

- ↑ Murray, Philip (2007-11-12). "Saltire and new Angus Flag will be pole buddies". Forfar Dispatch (Johnston Press Digital Publishing). Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- ↑ "Section 9: National Flags on number plates" (PDF). (PDF), INF104: Vehicle registration numbers and number plates. DVLA. 2009-04-27. Retrieved 2009-12-03.

- ↑ Jeffries, Hugh (2011). Stanley Gibbons Great Britain Concise Stamp Catalogue. Stanley Gibbons Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85259-808-5.

- ↑ "Symbols in Northern Ireland - Flags Used in the Region". CAIN Web Service. University of Ulster. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- ↑ "Marine and Fisheries - Compliance". Scottish Government. Retrieved 2011-09-28.

- ↑ "CalMac image". CalMac. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- ↑ "Waverley Excursions image". Waverley Excursions. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- ↑ "US Navy Signal Flags". United States Navy. 2009-08-17. Retrieved 2009-12-18.

- ↑ Bayer, Kurt (2007-11-25). "Article: Why sailors want to fly the (red) flag for Scotland; FLYING THE FLAG: James Ross wants recognition for the Scottish Red Ensign.". The Mail On Sunday (Associated Newspapers Ltd). Retrieved 2008-07-25.Partial view at HighBeam Research

- ↑ Wilson, Timothy; National Maritime Museum (Great Britain) (1986). Flags at sea: a guide to the flags flown at sea by British and some foreign ... HMSO. p. 66. ISBN 0-11-290389-4.

Scottish red ensign 17th-18th century

Google Books - ↑ "1yd Scottish Ensign". www.duncanyacht.co.uk. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ↑ "Supply of Flags" (PDF). PDF, Proper use of the Saltire. The Scottish Flag Trust. n.d. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

- ↑ "The Scottish Flag Trust: "Scottish Red Ensign" (.jpg image)". Scots Independent Newspaper. Retrieved 2009-12-18.

- ↑ "Saint Andrew and his flag". Scots History Online. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- ↑ "Symbols of the Monarchy: Union Jack". Royal Website. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- ↑ Bartram, Graham (2008-10-18). "British flags". The Flag Institute. Retrieved 2009-12-14.

- ↑ Fox-Davies, Arthur Charles (1904) [1986]. The Art of Heraldry: An Encyclopædia of Armory. London: Bloomsbury Books. p. 399. ISBN 0-906223-34-2.

- ↑ Perrin, William G (1922). British Flags; Their Early History and their Development at Sea, with an Account of the Origin of the Flag as a National Device. Oxford University Press. p. 207. Google Books

- ↑ National Library of Scotland, Slezer's Scotland. Accessed 04 July 2010

- ↑ Bartram, Graham (2005). British Flags & Emblems. Flag Institute/Tuckwell. p. 122. Google books: "Unofficial 1606 Scottish Union Flag"

- ↑ Crampton, William (1992). Flags of the World.

- ↑ Smith, Whitney (1973). The Flag Bulletin. Flag Research Center.

- ↑ Beaumont, John (1704) [First published 1701)]. The Present State of the Universe: Or an Account of I. The Rise, Births, Names, ... of All the Present Chief Princes of the World. ... Benj. Motte, and are to be sold by John Nutt, 1704. p. 164.

- ↑ "Slezer's Scotland". National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 2010-09-08.

- ↑ John Slezer, Robert Sibbald and Abel Swall (1693). Theatrum Scotiae: Containing the prospects of their Majesties castles and palaces: together with those of the most considerable towns and colleges; the ruins of many ancient abbeys, churches, monasteries and convents, within the said kingdom. All curiously engraven on copper plates. With a short ... John Leake. p. 114.

- 1 2 "Slezer's Scotland". National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 2010-09-08.

- ↑ "Slezer's Scotland". National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 2010-09-08.

- 1 2 3 de Burton, Simon (1999-11-09). "How Scots lost battle of the standard". The Scotsman (Johnston Press plc). Retrieved 2009-06-30. Partial view at Encyclopedia.com

- ↑ "United Kingdom - History of the Flag". Flags of the World. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- ↑ Smith, Whitney (1973). The Flag Bulletin. Flag Research Center.

- ↑ "Unofficial Scottish Union 1606 Flag". Flying Colours Flagmakers. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ↑ "Scottish Union (.jpg image)". boonjiepam (Flickr). Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ↑ Mair, George (2006-06-21). "Let's have a Scottish version of Union flag, says historian". The Scotsman. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ "Union Jack". The official website of the British Monarchy. Retrieved 2010-09-08.

- ↑ "Public Flag, Tartan Images". Communications Nova Scotia. 2007-05-29. Archived from the original on 2 December 2009. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- ↑ "Gemeentevlag" (in Dutch). Gemeente Sint-Oedenrode. Retrieved 2009-12-11.

- ↑ Innes of Learney, Sir Thomas (1934). Scots heraldry: a practical handbook on the historical principles and modern application of the art and science. Oliver and Boyd. p. 186. Google Books

- ↑ Tytler, Patrick F (1845). History of Scotland Volume 2, 1149-1603. William Tait. p. 433. Google Books

- 1 2 "The "Lion Rampant" Flag". The Court of the Lord Lyon. Retrieved 2008-10-10.

- ↑ "Union Jack". The Royal Household. Retrieved 2009-08-28.

External links

![]() Media related to Flags of Scotland at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Flags of Scotland at Wikimedia Commons

- The Court of the Lord Lyon website

- The Scottish Government - Flag Flying Guidance website

- The British Monarchy - Official website

- Petition Number 512

- Saint Andrew in the National Archives of Scotland

- The Saltire - Scotland's national flag at VisitScotland