Primrose League

The Primrose League was an organisation for spreading Conservative principles in Great Britain. It was founded in 1883 and active until the mid-1990s. It was finally wound up in December 2004.

At a late point in its existence, its declared aims (published in the Primrose League Gazette, vol.83, no.2, March/April 1979) were:

- To Uphold and support God, Queen, and Country, and the Conservative cause;

- To provide an effective voice to represent the interests of our members and to bring the experience of the Leaders to bear on the conduct of public affairs for the common good;

- To encourage and help our members to improve their professional competence as leaders;

- To fight for free enterprise.

Foundation

The primrose was known as the "favourite flower" of Benjamin Disraeli, and so became associated with him. Queen Victoria sent a wreath of primroses to his funeral on 26 April 1881 with the handwritten message: "His favourite flowers: from Osborne: a tribute of affectionate regard from Queen Victoria".[1] On the day of the unveiling of Disraeli's statue all Conservative members of the House of Commons were decorated with the primrose.[1]

A small group had for some time discussed the means for obtaining the support of the people for Conservative principles. Sir Henry Drummond Wolff said to Lord Randolph Churchill, "Let us found a primrose league".[1] A meeting was held at the Carlton Club shortly afterwards, consisting of Churchill, Wolff, Sir John Gorst, Percy Mitford, Colonel Fred Burnaby and some others, to whom were subsequently added Satchell Hopkins, J. B. Stone, Rowlands and some Birmingham supporters of Burnaby, who also wished to return Lord Randolph Churchill as a Conservative member for that city. These founding members assisted in remodelling the original statutes, first drawn up by Wolff. Wolff had for some years perceived the influence exercised in benefit societies by badges and titular appellations, and he endeavoured to devise some quaint phraseology that would be attractive to the working classes. The title of "Knight Harbinger" was taken from an office no longer existing in the Royal Household, and a regular gradation was instituted for the honorific titles and decorations assigned to members. This idea, though at first ridiculed, was greatly developed since the foundation of the order; and new distinctions and decorations were founded, also contributing to the attractions of the league.[1]

I declare on my honour and faith that I will devote my best ability to the maintenance of religion, of the estates of the realm, and of the imperial ascendancy of the British Empire; and that, consistently with my allegiance to the sovereign of these realms, I will promote with discretion and fidelity the above objects, being those of the Primrose League.[1]

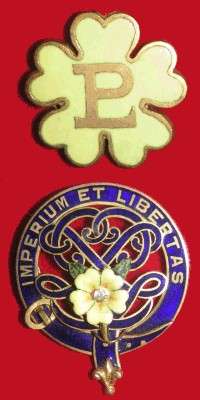

The motto was Imperium et libertas;[1] the seal, three primroses; and the badge, a monogram containing the letters PL, surrounded by primroses. Many other badges and various articles of jewellery were designed later, with this flower as an emblem.[1]

A small office was first taken on a second floor in Essex Street, The Strand; but this had soon to be abandoned, as the dimensions of the League rapidly increased.[1] The league had two types of members who paid different annual subscriptions: full members (knights and dames) who were usually charged half a crown, and associate members who paid a few pence.[2]

Ladies were generally included in the first organisation of the League, but subsequently a separate Ladies Branch and Grand Council were formed. The founder of the Ladies Grand Council was Lady Borthwick (afterwards Lady Glenesk), and the first meeting of the committee took place at her house in Piccadilly in March 1885.[1] "The Primrose League was the first political organisation to give women the same status and responsibilities as men".[2] The ladies who formed the first committee were: Lady Borthwick; the Dowager Duchess of Marlborough (first lady president); Lady Wimborne; Lady Randolph Churchill; Lady Charles Beresford; the Dowager Marchioness of Waterford; Julia, Marchioness of Tweeddale; Julia, Countess of Jersey; Mrs (subsequently Lady) Hardman; Lady Dorothy Nevill; the Honorable Lady Campbell (later Lady Blythswood); the Honorable Mrs Armitage; Mrs Bischoffsheim; Miss Meresia Nevill (the first secretary of the Ladies Council).[1]

| Year | Knights | Dames | Assoc- iates | Total | Habita- tions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1884 | 747 | 153 | 57 | 957 | 46 |

| 1885 | 1,071 | 1,381 | 1,914 | 11,366 | 169 |

| 1886 | 32,645 | 23,381 | 181,257 | 237,283 | 1,200 |

| 1887 | 50,258 | 39,215 | 476,388 | 565,861 | 1,724 |

| 1888 | 54,580 | 42,791 | 575,235 | 672,606 | 1,877 |

| 1889 | 58,108 | 46,216 | 705,832 | 810,228 | 1,986 |

| 1890 | 60,795 | 48,796 | 801,261 | 910,852 | 2,081 |

| 1891 | 63,251 | 50,973 | 887,068 | 1,001,292 | 2,143 |

| 1901 | 75,260 | 64,906 | 1,416,473 | 1,556,639 | 2,292 |

| 1910 | 87,235 | 80,038 | 1,885,746 | 2,053,019 | 2,645 |

When the league had become a success it was joined by Lord Salisbury and Sir Stafford Northcote, who were elected Grand Masters. Between its inauguration and 1910 its numbers gradual increased as may be see by the table to the right:[1]

Sir Winston Churchill, in his book on his father, Lord Randolph Churchill published in 1906, stated that, the Primrose League had one million paid up members "determined to promote the cause of Toryism".[3]

Membership of the League was "well over a million by the early 1890s" and at that time enjoyed more support than the British trade union movement.[4] 6,000 people were members of the League in Bolton in 1900, as large as the national membership of the Independent Labour Party during the same time.[5] However, by 1912 the League's membership had fallen to just over 650,000 as other leagues emerged, such as the Tariff Reform League and the Budget Protest League.[6]

With the granting of universal suffrage after the First World War, the Conservative Party leadership decided "A mass membership now seemed a necessary object if the Conservatives were to be on an equal footing with the mass battalions of the trade unions",[7] and so with the scaling up of party membership the need for ancillary support from organisations such as the Primrose League diminished, particularly as a conduit of female support who had now gained the vote and could be full members of the Conservative Party.[2]

Activities

Members were expected to actively support the league, and to keep up interest a programme of social events was organised for the membership "of which the Primrose summer fête, often held in the grounds of stately homes opened for the first time for this purpose, provided the grand annual climax".[2] That the events the members would often be addressed by, and have the opportunity to meet members of the Parliamentary Conservative Party.

Prior to World War II, the League was still able to pack the Royal Albert Hall for its annual Grand Habitation. It continued its activities after the war and celebrated its centenary in 1983 with its usual round of social and political events.

The League's Gazette carried articles by leading politicians of the day, even Margaret Thatcher (September/October 1977), but following the resignation of its industrious secretary of 45 years, Evelyn Hawley, C.B.E., at the end of 1988, it went into terminal decline.

Disbandment

The Daily Telegraph reported on 16 December 2004, "this week saw a significant event for any observers of political history: after 121 years, the Primrose League was finally wound up. The league's aim was to promote Toryism across the country. 'In recent years, our meetings have become smaller and smaller,' says Lord Mowbray, one of the league's leading lights. Its remaining funds have been donated to Tory coffers. 'On Monday, I presented Michael Howard and Liam Fox with a cheque for £70,000,' adds Lord Mowbray proudly."

Since Mowbray's actions, many Tory members have expressed disquiet at the disbandment. In addition, a domain name has been registered, suggesting the League may surface again at some point.

Administration

- Grand Masters: ; Lord Salisbury, Sir Stafford Northcote, Sir Winston Churchill (1944–1965), Alec Douglas-Home Lord Home of the Hirsel, KT, (1966 - Dec 1983).

- Chancellors: The Lord Mowbray and Stourton (April 1975 - April 1979) (April 1981 - April 1984), The Lord O'Hagan, MEP, (April 1979 - April 1981), The Lord Murton of Lindisfarne, OBE, TD, JP, (from April 1984 - Dec 1988), Sir John Langford-Holt, (1989 - ).

- Hon. Treasurer: Sir Graham Rowlandson, MBE, JP, (in 1977 - June 1985), Mr. W.L.Grant (June 1985 - August 1988), Peter Bowring (Sept 1988 - ).

- Chairman, Churchill Chapter, Geoffrey Johnson-Smith, MP (in 1977 - )

- Chairman, Ladies' Churchill Chapter: Mrs Evelyn King (in 1977 - June 1986), Judith, Lady Roberts (June 1985 - )

- Chairman, General Purposes Committee: John Heydon Stokes, MP (in 1971 - June 1985), William Cash, MP (from June 1985 - July 1988), Richard W.L. Smith (July 1988 - ).

- Chairman, Political Committee: Richard W.L. Smith (from April 1987 - )

- Secretary: (1943 - 1988 incl.) Mrs Evelyn M. Hawley, CBE, OBE.

- Hon. Director, Roger Boaden, MBE, (27 Sept 1988 - )

- Trustees: Col. Sir Leonard Ropner, Bt, MC,(1977); The Lord St. Helens, MC., (in 1977 - Dec 1980), The Lord Tweedsmuir, CBE., Robert Cooke, MP., (in 1977 - June 1987), The Lord Mowbray and Stourton, CBE, (from March 1980 - ) The Lord Denham, PC, (from April 1988 - ).

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Wolff 1911, p. 341.

- 1 2 3 4 Cooke 2014.

- ↑ Primrose League Gazette 82. March–April 1978.

- ↑ Seldon & Snowdon 2004, p. 211.

- ↑ Seldon & Snowdon 2004, pp. 211–212.

- ↑ Seldon & Snowdon 2004, p. 212.

- ↑ Cooke 2014 cites Pugh, p. 178

References

- Cooke, Alistair (September 2014). "Founders of the Primrose League (act. 1883–c.1918)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/42172. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Seldon, Anthony; Snowdon, Peter (2004). The Conservative Party. Sutton Publishing. pp. 211–212.

Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wolff, Henry Drummond (1911). "Primrose League, The". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 341.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wolff, Henry Drummond (1911). "Primrose League, The". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 341.

Further reading

- The Primrose League Gazette (originally bi-monthly, later quarterly). Quality paper, sized in between A4 and A5, some photos. (1989 editions in tabloid newspaper form). Editors: Mr Greenland (retired Dec 1976), William Cash, MP (1977 - Dec 1979), John Stokes (Jan/Feb, March, & April 1980 editions), Stephen Parker (May 1980 - 1989 incl).