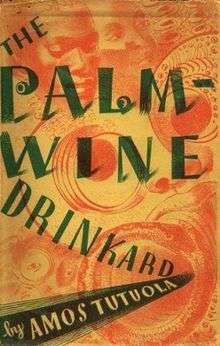

The Palm-Wine Drinkard

First edition (UK) | |

| Author | Amos Tutuola |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Publisher |

Faber and Faber (UK) Grove Press (US) |

Publication date |

1952 (UK) 1953 (US) |

| Pages | 125 |

| ISBN | 0-571-04996-6 |

| Followed by | My Life in the Bush of Ghosts |

The Palm-Wine Drinkard (subtitled "and His Dead Palm-Wine Tapster in the Dead's Town") is a novel published in 1952 by the Nigerian author Amos Tutuola. The first African novel published in English outside of Africa, this quest tale based on Yoruba folktales is written in a modified Yoruba English or Pidgin English. In it, a man follows his brewer into the land of the dead, encountering many spirits and adventures. The novel has always been controversial, inspiring both admiration and contempt among Western and Nigerian critics, but has emerged as one of the most important texts in the African literary canon, translated into over a dozen languages.

Plot

The Palm-Wine Drinkard, told in the first person, is about an unnamed man who is addicted to palm wine, which is made from the fermented sap of the palm tree and used in ceremonies all over West Africa. The son of a rich man, the narrator can afford his own tapster (a man who taps the palm tree for sap and then prepares the wine). When the tapster dies, cutting off his supply, the desperate narrator sets off for Dead's Town to try to bring the tapster back. He travels through a world of magic and supernatural beings, surviving various tests and finally gains a magic egg with never-ending palm wine.

Criticism

The Palm-Wine Drinkard was widely reviewed in Western publications when it was published by Faber and Faber. In 1975, the Africanist literary critic Bernth Lindfors produced an anthology of all the reviews of Turtuola's work published to date.[1] The first review was a rave from Dylan Thomas,[2] the Welsh poet who would die the following year of alcoholism and whose lyrical 500-word review of the drinker’s tale drew attention to Tutuola’s work and set the tone for succeeding criticism.[3] Thomas's own surreal imagery and folkloric grounding seems to have given him a special ear for Tutuola’s novel, saying it was "simply and carefully described" in "young English." Indeed, as Tutuola’s was the first African novel published in English outside of the continent, Thomas can be said to have launched the literary criticism of the Anglophone African novel in the West.

The early reviewers after Thomas, however, consistently described the book as "primitive,"[4] "primeval,"[5] "naïve,"[6] "un-willed,"[7] "lazy,"[8] and "barbaric" or "barbarous."[9] The New York Times Book Review was typical in describing Tutuola as "a true primitive" whose world had "no connection at all with the European rational and Christian traditions," adding that Tutuola was "not a revolutionist of the word, …not a surrealist" but an author with an "un-willed style" whose text had "nothing to do with the author’s intentions."[10] The New Yorker took this prejudice to its logical ends, stating that Tutuola was “being taken a great deal too seriously” as he is just a “natural storyteller" with a "lack of inhibition" and an "uncorrupted innocence" whose text was not new to anyone who had been raised on "old-fashioned nursery literature."[11] The reviewer concluded that American authors should not imitate Tutuola, as "it would be fatal for a writer with a richer literary inheritance." In The Spectator, Kingsley Amis called the book an "unfathomable African myth," but credited it with a "unique grotesque humour" that is a "severe test" for the reader.[12]

Given these Western reviews, it is not surprising that African intellectuals of the time saw the book as bad for the race, believing that the story showed Nigerians as illiterate and superstitious drunks. They worried that the novel confirmed Europeans’ racist "fantastic" concepts of Africa, "a continent of which they are profoundly ignorant."[13] Some criticized the novel as unoriginal, labeling it as little more than a retelling of Yoruba tales heard in the village square and Tutuola as "merely" a story teller who embellished stories for a given audience.[14] Some insisted that Tutuola’s "strange lingo" was related to neither Yoruba nor West African Pidgin English.[15]

It was only later that the novel began to rise in the general estimation. Critics began to value Tutuola's literary style as a unique exploration of the possibilities of African folklore instead of the more typical realist imitation of European novels in African novels.[16] One of the contributions Tutuola made was to "kill for ever any idea that Africans are copyists of the cultures of other races."[17] Tutuola was seen as a "pioneer of a new literary form, based on an ancient verbal style."[18] Rather than seeing the book as mere pastiche, critics began to note that Tutuola had done a great deal "to impose an extra-ordinary unity upon his apparently random collection of traditional material" and that what may have started as "fragments of folklore, ritual and belief" had "all passed through the transmuting fire of an individual imagination.”[19] The Nigerian critic E. N. Obiechina argued that the narrator’s “cosmopolitanism" enables him "to move freely through the rigdidly partitioned world of the traditional folk-tale." In contrast to the works of an author like Kafka, he added, in which human beings are the impotent victim of inexorable fate, the narrator of The Palm Wine Drinkard "is the proud possessor of great magical powers with which he defies even Fate itself."[20] The lack of resolution in the novel was also seen as more authentic, meant to enable group discussion in the same way that African riddles, proverbs, and folktales did. Tutuola was no more ungrammatical than James Joyce or Mark Twain, whose use of dialect was more violent, others argued.[21] The Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe also defended Tutuola's work, stating that it could be read a moral commentary on Western consumerism.

Well aware of the criticism, Tutuola has stated that he had no regrets, "Probably if I had more education, that might change my writing or improve it or change it to another thing people would not admire. Well, I cannot say. Perhaps with higher education, I might not be as popular a writer. I might not write folktales. I might not take it as anything important. I would take it as superstition and not write in that line."[22] He also added "I wrote The Palm-Wine Drinkard for the people of the other countries to read the Yoruba folklores. ... My purpose of writing is to make other people to understand more about Yoruba people and in fact they have already understood more than ever before."[23]

Although The Palm-Wine Drinkard is often described as magical realism, the term was not invented until 1955, after the novel was published.

In popular culture

Kool A.D., one of the rappers in Das Racist, released a mixtape of the same name in 2012.

Law and Order SVU character Detective Odafin "Fin" Tutuola's name is derived from this novel.

Canadian rock band The Stills named a track on their 2008 album Oceans Will Rise after the book.

References

- ↑ Lindfors, Bernth (1975). Critical Perspectives on Amos Tutuola. Washington, DC: Three Continents Press.

- ↑ Thomas, Dylan (6 July 1952). "Blithe Spirits". The Observer.

- ↑ Lindfors (1975). Critical Perspectives on Amos Tutuola. p. 7.

- ↑ Lindfors (1975). Critical Perspectives on Amos Tutuola. pp. 10, 15, 22, 25, 77, 91.

- ↑ Lindfors (1975). Critical Perspectives on Amos Tutuola. p. 87.

- ↑ Lindfors (1975). Critical Perspectives on Amos Tutuola. pp. 15, 18, 49.

- ↑ Lindfors (1975). Critical Perspectives on Amos Tutuola. p. 15.

- ↑ Lindfors (1975). Critical Perspectives on Amos Tutuola. p. 21.

- ↑ Lindfors (1975). Critical Perspectives on Amos Tutuola. pp. 18, 21.

- ↑ Rodman, Selden (20 September 1953). "Book Review of Palm-Wine Drinkard". New York Times Book Review.

- ↑ West, Anthony (5 December 1953). "Book Review of Palm-Wine Drinkard". New Yorker.

- ↑ Lindfors (1975). Critical Perspectives on Amos Tutuola. p. 26.

- ↑ Lindfors (1975). Critical Perspectives on Amos Tutuola. p. 41.

- ↑ Palmer, Eustace (1978). "Twenty-five years of Amos Tutuola". The International Fiction Review 5 (1). Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ↑ Lindfors (1975). Critical Perspectives on Amos Tutuola. p. 31.

- ↑ Chouldhury, Saradashree (October 2013). "Folklore and society in transition: A study of The PalmWine Drinkard and The Famished Road" (PDF). African Journal of History and Culture 6 (1): 3–11. doi:10.5897/AJHC2013.0158. Retrieved 21 Jan 2015.

- ↑ Lindfors (1975). Critical Perspectives on Amos Tutuola. p. 44.

- ↑ Staff Writer (1 May 1954). "Portrait: A Life in the Bush of Ghosts". West Africa.

- ↑ Lindfors (1975). Critical Perspectives on Amos Tutuola. p. 51.

- ↑ Abiechina, E. N. (1968). "Amos Tutuola and the Oral Tradition". Présence Africaine: 85–106.

- ↑ Lo Liyong, Taban (1968). "Tutuola, Son of Zinjanthropus". Busara.

- ↑ Lindfors, Bernth (1999). The Blind Men and the Elephant and Other Essays in Biographical Criticism. Africa World Press. p. 143.

- ↑ Lindfors (1975). Critical Perspectives on Amos Tutuola.

External links

- Petri Liukkonen. "Amos Tutuola". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Archived from the original on 4 July 2013.

- Michael Swanwick discussing the book and Tutuola

|