The Name of the Rose

First edition (Italian) | |

| Author | Umberto Eco |

|---|---|

| Original title | Il nome della rosa |

| Country | Italy |

| Language | Italian |

| Genre | Historical novel, Mystery |

| Publisher |

Bompiani (Italy) Harcourt (US) |

Publication date | 1980 |

Published in English | 1983 |

| Media type | Print (Paperback) |

| Pages | 512 pp |

| ISBN | 0-15-144647-4 |

| OCLC | 8954772 |

| 853/.914 19 | |

| LC Class | PQ4865.C6 N613 1983 |

The Name of the Rose (Italian: Il nome della rosa [il ˈnoːme della ˈrɔːza]) is the 1980 debut novel by Italian author Umberto Eco. It is a historical murder mystery set in an Italian monastery, in the year 1327, an intellectual mystery combining semiotics in fiction, biblical analysis, medieval studies, and literary theory. It was translated into English by William Weaver in 1983.

Plot summary

Franciscan friar William of Baskerville and Adso of Melk, a Benedictine novice travelling under his protection, arrive to a Benedictine monastery in Northern Italy to attend a theological disputation. Upon their coming, the monastery is disturbed by a suicide. As the story unfolds, several other monks die under mysterious circumstances. William is tasked by the monastery's abbot to investigate the deaths, and fresh clues with each murder victim lead William to dead ends and new clues. The protagonists explore a labyrinthine medieval library, discuss the subversive power of laughter, and come face to face with the Inquisition, a reaction to the Waldensians, a heresy which started in the 12th century and claimed to advocate an adherence to the Gospel as taught by Jesus and his disciples. William's innate curiosity and highly developed powers of logic and deduction provide the keys to unraveling the abbey's mysteries.

Characters

- Primary characters

- William of Baskerville—main protagonist, a Franciscan friar

- Adso of Melk—narrator, Benedictine novice accompanying William

- At the monastery

- Abo of Fossanova—the abbot of the Benedictine monastery

- Severinus of Sankt Wendel—herbalist who helps William

- Malachia of Hildesheim—librarian

- Berengar of Arundel—assistant librarian

- Adelmo of Otranto—illuminator, novice

- Venantius of Salvemec—translator of manuscripts

- Benno of Uppsala—student of rhetoric

- Alinardo of Grottaferrata—eldest monk

- Jorge of Burgos—elderly blind monk

- Remigio of Varagine—cellarer

- Salvatore of Montferrat—monk, associate of Remigio

- Nicholas of Morimondo—glazier

- Aymaro of Alessandria—gossipy, sneering monk

- Pacificus of Tivoli

- Peter of Sant’Albano

- Waldo of Hereford

- Magnus of Iona

- Patrick of Clonmacnois

- Rabano of Toledo

- Outsiders

- Ubertino of Casale—Franciscan friar in exile, friend of William

- Michael of Cesena—Minister General of the Franciscans

- Bernardo Gui—Inquisitor

- Bertrand del Poggetto—Cardinal and leader of the Papal legation

- Peasant girl from the village below the monastery

Major themes

Eco, being a semiotician, is hailed by semiotics students who like to use his novel to explain their discipline. The techniques of telling stories within stories, partial fictionalization, and purposeful linguistic ambiguity are all apparent. The solution to the central murder mystery hinges on the contents of Aristotle's book on Comedy, of which no copy survives; Eco nevertheless plausibly describes it and has his characters react to it appropriately in their medieval setting – which, though realistically described, is partly based on Eco's scholarly guesses and imagination. It is virtually impossible to untangle fact and history from fiction and conjecture in the novel. Through the motif of this lost and possibly suppressed book which might have aestheticized the farcical, the unheroic and the skeptical, Eco also makes an ironically slanted plea for tolerance and against dogmatic or self-sufficient metaphysical truths – an angle which reaches the surface in the final chapters.[1]

Umberto Eco is a significant postmodernist theorist and The Name of the Rose is a postmodern novel.[2] The quote in the novel, "books always speak of other books, and every story tells a story that has already been told," refers to a postmodern idea that all texts perpetually refer to other texts, rather than external reality.[2] In true postmodern style, the novel ends with uncertainty: "very little is discovered and the detective is defeated" (postscript). William of Baskerville solves the mystery in part by mistake; he thought there was a pattern but, in fact, numerous "patterns" were involved and combined with haphazard mistakes by the killers. William concludes in fatigue that there "was no pattern". Thus Eco turns the modernist quest for finality, certainty and meaning on its head, leaving the overall plot partly the result of accident and arguably without meaning.[2] Even the novel's title alludes to the possibility of many meanings or of nebulous meaning; Eco saying in the Postscript he chose the title "because the rose is a symbolic figure so rich in meanings that by now it hardly has any meaning left".[3]

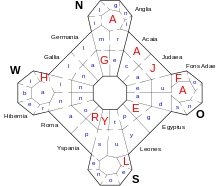

The aedificium's labyrinth

The mystery revolves around the abbey library, situated in a fortified tower—the aedificium. This structure has three floors—the ground floor contains the kitchen and refectory, the first floor a scriptorium, and the top floor is occupied by the library.[4] The two lower floors are open to all, while only the librarian may enter the last. A catalogue of books is kept in the scriptorium, where manuscripts are read and copied. A monk who wishes to read a book would send a request to the librarian, who, if he thought the request justified, would bring it to the scriptorium. Finally, the library is in the form of a labyrinth, whose secret only the librarian and the assistant librarian know.[5]

The aedificium has four towers at the four cardinal points, and the top floor of each has seven rooms on the outside, surrounding a central room. There are another eight rooms on the outer walls, and sixteen rooms in the centre of the maze. Thus, the library has a total of fifty-six rooms.[6] Each room has a scroll containing a verse from the Book of Revelation. The first letter of the verse is the letter corresponding to that room.[7] The letters of adjacent rooms, read together, give the name of a region (e.g. Hibernia in the West tower), and those rooms contain books from that region. The geographical regions are:

- Fons Adae, 'The earthly paradise' contains Bibles and commentaries, East Tower

- Acaia, Greece, Northeast

- Iudaia, Judea, East

- Aegyptus, Egypt, Southeast

- Leones, 'South' contains books from Africa, South Tower

- Yspania, Spain, Southwest outer

- Roma, Italy, Southwest inner

- Hibernia, Ireland, West Tower

- Gallia, France, Northwest

- Germania, Germany, North

- Anglia, England, North Tower

Two rooms have no lettering - the easternmost room, which has an altar, and the central room on the south tower, the so-called finis Africae, which contains the most heavily guarded books, and can only be entered through a secret door. The entrance to the library is in the central room of the east tower, which is connected to the scriptorium by a staircase.[8]

Title

Much attention has been paid to the mystery the book's title refers to. In fact, Eco has stated that his intention was to find a "totally neutral title".[3] In one version of the story, when he had finished writing the novel, Eco hurriedly suggested some ten names for it and asked a few of his friends to choose one. They chose The Name of the Rose.[9] In another version of the story, Eco had wanted the neutral title Adso of Melk, but that was vetoed by his publisher, and then the title The Name of the Rose "came to me virtually by chance."

The book's last line, "Stat rosa pristina nomine, nomina nuda tenemus" translates as: "the rose of old remains only in its name; we possess naked names." The general sense, as Eco pointed out,[10] was that from the beauty of the past, now disappeared, we hold only the name. In this novel, the lost "rose" could be seen as Aristotle's book on comedy (now forever lost), the exquisite library now destroyed, or the beautiful peasant girl now dead. We only know them by the description Adso provides us — we only have the name of the book on comedy, not its contents. As Adso points out at the end of the fifth day, he does not even know the name of the peasant girl to lament her. Does this mean she does not endure at all?

This text has also been translated as "Yesterday's rose stands only in name, we hold only empty names." This line is a verse by twelfth century monk Bernard of Cluny (also known as Bernard of Morlaix). Medieval manuscripts of this line are not in agreement (but the best read "Roma" instead of "rosa"). Roma here introduces a "false" quantity, with a long-o for the Classical short-o; thus, a scribe may have written the "classically impeccable" rosa, which betrays the overall context and flexible prosody of Bernard. Eco quotes one Medieval variant verbatim,[11] but Eco was not aware at the time of the text more commonly printed in modern editions, in which the reference is to Rome (Roma), not to a rose (rosa).[12] The alternative text, with its context, runs: Nunc ubi Regulus aut ubi Romulus aut ubi Remus? / Stat Roma pristina nomine, nomina nuda tenemus. This translates as "Where now is Regulus, or Romulus, or Remus? / Primordial Rome abides only in its name; we hold only naked names." See the new excellent source edition of 2009: Bernard of Cluny, De contemptu mundi: Une vision du monde vers 1144, ed. and trans. A. Cresson, Témoins de notre histoire (Turnhout, 2009), p. 126 (bk. 1, 952), and note thereto p. 257.

Also the title of the book may be related to a poem by the Mexican poet and mystic Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1651–1695):

Rosa que al prado, encarnada,

te ostentas presuntuosa

de grana y carmín bañada:

campa lozana y gustosa;

pero no, que siendo hermosa

también serás desdichada.

which appears in Eco's Postscript to the Name of the Rose, and is translated into English in "Note 1" of that book as:

Red rose growing in the meadow,

you vaunt yourself bravely

bathed in crimson and carmine:

a rich and fragrant show.

But no: Being fair,

You will be unhappy soon.[3]

Allusions

To other works

The historical novel with medieval time setting was re-discovered in Italy a short time before by Italo Alighiero Chiusano, with his L'ordalia. The similarities between the two novels (time setting, the fact that both are bildungsroman [coming-of-age novels], the novice main character, and the older monk mentor), and the notoriety that L′ordalia had in 1979,[13] of which an expert on literature such as Umberto Eco was definitely aware, making L'ordalia likely one of the first sources of inspiration of The Name of the Rose.

The name of the central character, William of Baskerville, alludes both to the fictional detective Sherlock Holmes (compare The Hound of the Baskervilles – also, Adso's description of William in the beginning of the book resembles, almost word for word, Dr. Watson's description of Sherlock Holmes when he first makes his acquaintance in A Study in Scarlet) and to William of Ockham (see the next section). The name of the narrator, his apprentice Adso of Melk is among other things a pun on Simplicio from Galileo Galilei's Dialogue; Adso = ad Simplicio ("to Simplicio"). Adso's putative place of origin, Melk, is the site of a famous medieval library, at Melk Abbey.

The blind librarian Jorge from Burgos is a nod to Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges, a major influence on Eco. Borges was blind during his later years and was also director of Argentina's national library; his short story "The Library of Babel" is a clear inspiration for the secret library in Eco's book: "The Library is composed of an indefinite, perhaps infinite, number of hexagonal galleries, with enormous ventilation shafts in the middle, encircled by very low railings." Another of Borges's stories, "The Secret Miracle," features a blind librarian. In addition, a number of other themes drawn from various of Borges's works are used throughout The Name of the Rose: labyrinths, mirrors, sects and obscure manuscripts and books.

The ending also owes a debt to Borges' short story "Death and the Compass," in which a detective proposes a theory for the behavior of a murderer. The murderer learns of the theory and uses it to trap the detective. In The Name of the Rose, the librarian Jorge uses William's belief that the murders are based on the Revelation of John to misdirect William, though in Eco's tale, the detective succeeds in solving the crime.

The "poisoned page" motif may have been inspired by Alexandre Dumas' novel La Reine Margot (1845). It was also used in the film Il giovedì (1963) by Italian director Dino Risi.[14]

Eco seems also to have been aware of Rudyard Kipling's short story "The Eye of Allah," which touches on many of the same themes, like optics, manuscript illumination, music, medicine, priestly authority and the Church's attitude to scientific discovery and independent thought, and which also includes a character named John of Burgos.

Throughout the book, there are Latin quotes, authentic and apocryphal. There are also discussions of the philosophy of Aristotle and of a variety of millenarist heresies, especially those associated with the fraticelli. Numerous other philosophers are referenced throughout the book, often anachronistically, including Wittgenstein.

To actual history and geography

William of Ockham, who lived during the time at which the novel is set, first put forward the principle known as Ockham's Razor, often summarised as the dictum that one should always accept as most likely the simplest explanation that accounts for all the facts (a method used by William of Baskerville in the novel).

The book describes monastic life in the 14th century. The action takes place at a Benedictine abbey during the controversy surrounding the Apostolic poverty between branches of Franciscans and Dominicans; (see renewed controversy on the question of poverty). The setting was inspired by monumental Saint Michael's Abbey in Susa Valley, Piedmont and visited by Umberto Eco.[15] The Spirituals abhor wealth, bordering on the Apostolics or Dulcinian heresy. The book highlights this tension that existed within Christianity during the medieval era: the Spirituals, one faction within the Franciscan order, demanded that the Church should abandon all wealth, and some heretical sects began killing the well-to-do, while the majority of the Franciscans and the clergy took to a broader interpretation of the gospel.

A number of the characters, such as the Inquisitor Bernard Gui (as Bernardo Gui), Ubertino of Casale and the Minorite Michael of Cesena (as Michele da Cesena), are historical figures, though the novel's characterization of them is not always historically accurate. Dante Alighieri and his Comedy are mentioned once in passing. However, Eco notes in a companion book that he had to site the monastery in mountains so it would experience early frosts, in order for that action to take place at a time when the historical Bernard Gui could have been in the area. For the purposes of the plot, Eco needed a quantity of pig blood, but at that time pigs were not usually slaughtered until a frost had arrived. Later in the year, Gui was known to have been away from Italy and could not have participated in the events at the monastery.

Part of the dialogue in the inquisition scene of the novel is lifted bodily from the historical Gui's own Manual for Inquisitors, the Practica Inquisitionis Heretice Pravitatis, for example the dialogue: "What do you believe?" "What do you believe, my Lord?" "I believe in all that the Creed teaches." "So I believe, My Lord." Bernardo then points out that what Remigius the cellarer is saying is not that Remigius believes in the Creed, but that Remigius believes that Bernardo believes in the Creed. This is an example given by the historical Gui in his book to warn inquisitors against the slipperiness and manipulation of words by heretics. This use of Gui's own book by Eco is self-consciously of a piece with his perspective that "books always speak of other books." In this case, the author integrates the historical Bernard Gui's text into his own through the fictional character of Bernardo.

Adso's description of the portal of the monastery is recognizably that of the portal of the church at Moissac, France. There is also a quick reference to a famous "Umberto of Bologna" – Umberto Eco himself.

Adaptations

Fiction

- My Name Is Red by Orhan Pamuk is deeply indebted to The Name of the Rose.

Film

- A film adaptation, eponymously titled The Name of the Rose (1986), was directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud, and starred Sean Connery as William of Baskerville and Christian Slater as Adso.[16]

Dramatic works

- A play adaptation by Grigore Gonţa had premiered at National Theatre Bucharest in 1998, starring Radu Beligan, Gheorghe Dinică, and Ion Cojar.

- A two-part radio drama based on the novel and adapted by Chris Dolan was broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on June 16 and 23, 2006.

- A radio parody inspired by the film adaptation was made as part of the Crème de la Crime series by Punt and Dennis, also on BBC Radio 4.

Games

- A Spanish video game adaptation was released in 1987 under the title La Abadía del Crimen (The Abbey of the Crime).

- Ravensburger published an eponymous boardgame in 2008, written by Stephan Feld and is based on the events of the book.

- An adventure video game adaptation titled, Murder in the Abbey (2008), was developed by Alcachofa Soft and published by DreamCatcher Interactive.

Music

- The British rock band Ten released the album The Name of the Rose (1996), whose eponymous track is loosely based around some of the philosophical concepts of the novel.

- The British metal band Iron Maiden released the song "Sign of the Cross" in 1995, part of their X Factor album. The song refers to the novel.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Lars Gustafsson, postscript to Swedish edition The Name of the Rose

- 1 2 3 Christopher Butler. Postmodernism: A Very Short Introduction. OUP, 2002. ISBN 978-0-19-280239-2 — see pages 32 and 126 for discussion of the novel.

- 1 2 3 "Postscript to the Name of the Rose", printed in The Name of the Rose (Harcourt, Inc., 1984), p. 506.

- ↑ First Day, Terce, paragraph 37

- ↑ First Day, Terce, paragraph 67

- ↑ Third Day, Vespers, paragraphs 50-56

- ↑ Third Day, Vespers, paragraphs 64-68

- ↑ Fourth Day, After Compline

- ↑ Umberto Eco. On Literature. Secker & Warburg, 2005, p. 129-130. ISBN 0-436-21017-7.

- ↑ "Name of the Rose: Title and Last Line". Archived from the original on 2007-01-21. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- ↑ Eco would have found this reading in, for example, the standard text edited by H.C. Hoskier (London 1929); only the Hiersemann manuscript preserves "Roma". For the verse quoted in this form before Eco, see e.g. Alexander Cooke, An essay on the origin, progress, and decline of rhyming Latin verse (1828), p. 59, and Hermann Adalbert Daniel, Thesaurus hymnologicus sive hymnorum canticorum sequentiarum (1855), p. 290. See further Pepin, Ronald E. "Adso's closing line in The Name of the Rose." American notes and queries (May–June 1986): 151–152.

- ↑ As Eco wrote in "The Author and his Interpreters" "Thus the title of my novel, had I come across another version of Morlay's poem, could have been The Name of Rome (thus acquiring fascist overtones)".

- ↑ "Letture", n. 614, February 2005: Memoria. Marco Beck ricorda Italo Alighiero Chiusano

- ↑ notes to Daniele Luttazzi. Lolito. pp. 514–15.

- ↑ Avosacra.it

- ↑ Canby, Vincent (September 24, 1986). "The Name of the Rose (1986) FILM: MEDIEVAL MYSTERY IN 'NAME OF THE ROSE'". The New York Times.

References

- Eco, Umberto (1983). The Name of the Rose. Harcourt.

- Coletti, Theresa (1988). Naming the Rose. Cornell University Press.

- Haft, Adele (1999). The Key to The Name of the Rose. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-08621-4

- Ketzan, Erik. "Borges and The Name of the Rose". Retrieved 2007-08-18.

- Wischermann, Heinfried (1997). Romanesque. Konemann.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Umberto Eco |

- Umberto Eco discusses The Name of the Rose on the BBC World Book Club

- IMDb.com Listing: The Name of the Rose

- Filming location Kloster Eberbach, Germany

- The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco, reviewed by Ted Gioia (Postmodern Mystery)

- New York Times Review

| ||||||||||||||

|