Church Mission Society

| |

| Abbreviation | CMS |

|---|---|

| Formation | 12 April 1799 |

| Founder | Clapham Sect |

| Type |

Evangelical Anglicanism Ecumenism Protestant missionary British Commonwealth |

| Headquarters |

Watlington Road Oxford OX4 6BZ United Kingdom |

| Website | cms-uk.org |

The Church Mission Society (CMS), formerly in Britain and currently in Australia and New Zealand known as the Church Missionary Society, is a mission society working with the Anglican Communion and Protestant Christians around the world. Founded in 1799, CMS has attracted over nine thousand men and women to serve as mission partners during its 200 year history. The society has also given its name "CMS" to a number of daughter organisations around the world.

History

Foundation

The original proposal for the mission came from Charles Grant and George Uday of the East India Company and the Revd David Brown, of Calcutta, who sent a proposal in 1787 to William Wilberforce, then a young member of parliament, and Charles Simeon, a young clergyman at Cambridge University.[1] The Baptist Missionary Society was formed in 1792 and the London Missionary Society was formed in 1795 to represent various demonimations that were part of the Evangelical Revival in the English Protestant churches.[1]

The Society for Missions to Africa and the East (as the society was first called) was founded on 12 April 1799 at a meeting of the Eclectic Society, supported by members of the Clapham Sect, a group of activist evangelical Christians. Their number included Charles Simeon, John Venn, Basil Woodd;[2][1] and also Henry Thornton, Thomas Babington[3] and William Wilberforce. Wilberforce was asked to be the first president of the society, but he declined to take on this role and became a vice-president. The treasurer was Henry Thornton and the founding secretary was Thomas Scott,[4] a biblical commentator. Many of the founders were also involved in creating the Sierra Leone Company and the Society for the Education of Africans.[5]

Development

In 1803 Josiah Pratt was appointed secretary, a position he held for 21 years, becoming an early driving force in the CMS. The first missionaries went out in 1804. They came from the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Württemberg and had trained at the Berlin Seminary. The name Church Missionary Society began to be used and in 1812 the society was renamed The Church Missionary Society.[1] The principal missions, the founding missionaries, and the dates of the establishment of the missions are:[6]

- West Africa (1804): Melchior Renner and Peter Hartwig were sent to the country of the Susu people in Guinea.[7] The West Africa mission was extended to Sierra Leone (1816). Samuel Ajayi Crowther, a Yoruba by birth, was selected to accompany the missionary James Frederick Schön on the Niger expedition of 1841. Crowther (later appointed first African Anglican bishop in Nigeria) was the principal missionary to Yorubaland in 1844 and the Niger in 1857.[6][7]

- New Zealand (1814): The Revd Samuel Marsden[8] became the chaplain of the penal colony at Paramatta, Australia in 1874.[9] Samuel Marsden attempted to establish a mission in the New Zealand in 1809, however it was not until 1814 that the CMS established a mission in Aotearoa (New Zealand) when he officiated at its first service on Christmas Day in 1814, at Oihi Bay in the Bay of Islands.[9]

- India (1814): William Carey, the founder of the Baptist Missionary Society was the pioneer of the Evangelical, Protestant missionary movement in India who arrived in 1793. The CMS sent 7 missionaries to India in 1814-1816: two were placed at Chennai (Madras), two at Bengal and three at Travancore (1816).[10] The Indian missions were extended in the following years to a number of locations including Agra, Meerut district, Varanasi (Benares), Mumbai (Bombay) (1820), Tirunelveli (Tinnevelly) (1820), Kolkata (Calcutta) (1822), Telugu Country (1841) and the Punjab region (1852).[6][10] While the Revolt of 1857 resulted in damage to the missions in the North West Provinces, after the revolt the CMS expanded its missions to Oudh, Allahbad, the Santhal people (1858), and to Kashmir (1865).[6][10]

- Sri Lanka (Ceylon) (1817): Four CMS missionaries were sent to Ceylon in 1817 and the following 5 years mission stations were established at Kandy, Baddegama, Kottawa (Cotta) and Jaffna. In 1850 a mission station was established at Colombo.[11]

- North West America Mission (Canada) (1822): The CMS provided financial assistance in 1820 to the Revd John West, chaplain to the Hudson’s Bay Company, towards the education of some native American children, including James Settee of the Swampy Cree nation,[12] Charles Pratt (Askenootow) and Henry Budd of the Cree nation. In 1822 the CMS appointed West to head the mission in what was then known as the Red River Colony in what is now the province of Manitoba.[13] He was succeeded in 1823 by the Revd David Jones who was joined by the Revd W. Cockram and his wife in 1825.[13] The mission worked among the Cree, Ojibwe, Chippewa, and Gwich'in (Tukudh) of the upper west Great Plains.[13] The North West America Mission was extended to the people of the Blackfoot Confederacy in Saskatchewan (1840),[14] to the Cree and Inuit of Hudson Bay (1851),[15][16][17] the Anishinaabe of Manitoba and towards the Arctic Circle to the Naskapi (Innu) (1858-1862).[13][6]

- Middle East (1815): The Revd William Jowett was appointed to commence the Mediterranean Mission, however the mission was only intermittently able to establish missions in Turkey in 1819-21 as the result of resistance to the Christian faith; an attempt in 1862 to open a mission station in Constantinople also failed.[18]

- Egypt (1825) and Ethiopia (1827): Five missionaries were sent to Egypt in 1825. The CMS concentrated the Mediterranean Mission on the Coptic Church and in 1830 to its daughter Ethiopian Church, which included the creation of a translation of the Bible in Amharic at the instigation of William Jowett, as well as the posting of two missionaries to Ethiopia (Abyssinia), Samuel Gobat (later the Anglican Bishop of Jerusalem) and Christian Kugler arrived in that country in 1827.[19] The missionaries were expelled from Abyssinia in 1844 following the Siege of Khartoum and the death of General Gordon.[18] The Egyptian Mission was revived in 1882 by Frederick Augustus Klein.[18]

- Australia (1825): The first missionaries arrived to serve in western New South Wales.

- East Africa (1844): The Revd Johann Ludwig Krapf was in Abyssinia, however when the missionaries were forced out he moved to Mombasa. CMS missionaries, such as Krapf and the Revd Johannes Rebmann, explored East and Central Africa, with Rebmann being the first European to reach Mount Kilimanjaro (1848) and Krapf was the first to reach Mount Kenya (1849).[7] The East Africa Mission was revived in 1874 and extended to inland Kenya (Nyanza Province at Lake Victoria) and Uganda (1876).[6][7] The Uganda mission centered in Kampala and was pioneered by missionary brothers Albert Ruskin Cook and John Howard Cook.

- China (1844): Robert Morrison, of the London Missionary Society established a mission in Guangzhou (Canton) in 1808. After the First Opium War, Hong Kong came under the control of Great Britain and ports on the mainland, including Canton and Shanghai, become open to Europeans. In 1844 the CMS sent the Revd George Smith (later Bishop of Victoria, H.K.) and the Revd T. McClatchie to establish a mission at Shanghai.[20]

- Palestine (1851): The Revd Frederick Augustus Klein arrived in Nazareth in 1851 where he lived for 5-6 years, then he moved to Jerusalem until 1877. In 1855 the Revd John Zeller was sent to Nablus. In 1857 he moved to Nazareth, where he stayed for the next 20 years, then he moved to Jerusalem.[18]

- Mauritius (1854): Bishop Vincent W Ryan was appointed the bishop of Mauritius in 1854 and the same year the Revd David Fenn established a mission station.[21]

- North Pacific Mission (British Columbia) (1857): William Duncan, a lay missionary, arrived at the remote Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) fort settlement at Lax Kw'alaams, British Columbia, then part of HBC's New Caledonia district and known as Fort Simpson or Port Simpson. His work included founding the Tsimshian communities of Metlakatla, British Columbia, in Canada, and Metlakatla, Alaska, in the United States.[22] The Revd R. S. Tugwell joined the mission in October 1860.[23] In the early 1870s the Revd William Collison served with Duncan in Metlakatla.[22] Collison extended the work of the North Pacific Mission to the Haida people of the archipelago of Haida Gwaii (formerly the Queen Charlotte Islands) in northern British Columbia. The Revd Robert Tomlinson, a medical missionary, re-established the Revd Robert A. Doolan's three-year-old Anglican mission among the Nisga'a people by relocating it from the lower Nass River to a newly established community, Kincolith (today known as Gingolx), at the mouth of the Nass River.[22]

- Madagascar (1863): Two CMS missionaries operated a mission station from 1863 until their deaths in 1864.[24]

- Japan (1868): The Revd George Ensor established a mission station at Nagasaki and in 1874 he was replaced by the Revd H Burnside. The same year the mission was expanded to include the Revd C. F. Warren at Osaka, the Revd Philip Fyson at Yokohama, the Revd J. Piper at Tokyo (Yedo), the Revd H. Evington at Niigata and the Revd W. Dening at Hokkaido.[25][26][27][28] The Revd H. Maundrell joined the Japan mission in 1875 and served at Nagasaki.[29] The Revd John Batchelor was a missionary to the Ainu people of Hokkaido from 1877 to 1941. Hannah Riddell arrived in Kumamoto, Kyūshū in 1891. She worked to establish the Kaishun Hospital (known in English as the Kumamoto Hospital of the Resurrection of Hope) for the treatment of Leprosy, with the hospital opening on 12 November 1895. Hannah Riddell left the CMS in 1900 to run the hospital.

- Persia (1869): Henry Martyn visited Persia in 1811, however a mission station was not established until 1868 when the Revd Robert Bruce established a mission station at Julfa in Ispahan.[30][31] After Bishop Edward Stuart resigned as the Bishop of Waiapu in New Zealand, he then served as a missionary in Julfa from 1894 to 1911.[32]

From the beginning of the organisation until 1894 the total number of CMS missionaries amounted to 1,335 (men) and 317 (women). During this period the indigenous clergy ordained by the branch missions totalled 496 and about 5,000 lay teachers had been trained by the branch missions.[6] In 1894 the active members of the CMS totaled: 344 ordained missionaries, 304 indigenous clergy (ordained by the branch missions) and 93 lay members of the CMS. As of 1894, in addition to the missionary work the CMS operated about 2016 schools, with about 84,725 students.[6]

In the first 25 years of the CMS nearly half the missionaries were Germans trained in Berlin and later from the Basel Seminary.[6] The Church Missionary Society College, Islington opened in 1825 and trained about 600 missionaries; about 300 joined the CMS from universities and about 300 came from other sources.[6] 30 CMS missionaries were appointed to the Episcopate, serving as bishops.[6]

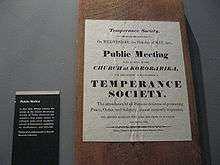

The CMS published The Church Missionary Gleaner, from April 1841 to September 1857.[33] From 1813 to 1855 the society published The Missionary Register, "containing an abstract of the principal missionary and bible societies throughout the world". From 1816, "containing the principal transactions of the various institutions for propagating the gospel with the proceedings at large of the Church Missionary Society".[34]

20th century

During the early twentieth century, the society's theology moved in a more liberal direction under the leadership of Eugene Stock.[35] There was considerable debate over the possible introduction of a doctrinal test for missionaries, which advocates claimed would restore the society's original evangelical theology. In 1922, the society split, with the liberal evangelicals remaining in control of CMS headquarters, whilst conservative evangelicals established the Bible Churchmen's Missionary Society (BCMS, now Crosslinks).

Notable general secretaries of the society later in the 20th century were Max Warren and John Vernon Taylor. The first woman president of the CMS, Diana Reader Harris, was instrumental in persuading the society to back the 1980 Brandt Report on bridging the North-South divide. In the 1990s CMS appointed its first non-British general secretary, Michael Nazir-Ali, who later became Bishop of Rochester in the Church of England, and its first women general secretary, Diana Witts.

At the end of the 20th century there was a significant swing back to the Evangelical position, probably in part due to a review in 1999 at the anniversary and also due to the re-integration of Mid Africa Ministry (formerly the Ruanda Mission). The position of CMS is now that of an ecumenical Evangelical society.

Present

On 31 January 2010 CMS had 151 mission partners and co-mission partners (workers jointly sent by CMS and another agency) serving in Africa, Asia, Europe and the Middle East. The 2009–10 Annual Review also lists "Other people in mission: 78"; "Cross-cultural programme participants: 126" and "Projects financially supported: 114". This does not take into account work in Latin America, which came with the integration of CMS and the South American Mission Society on 1 February 2010. In 2009–10, CMS had a budget of £8 million, drawn primarily from donations by individuals and parishes, supplemented by historic investments.[36]

In 2004 CMS was instrumental in bringing together a number of Anglican and, later, some Protestant mission agencies to form Faith2Share, an international network of mission agencies.

In June 2007, CMS in Britain moved the administrative office out of London for the first time. It is now based with the new Crowther Centre for Mission Education[37] in east Oxford.

In 2008, CMS was acknowledged as a mission community by the Advisory Council on the Relations of Bishops and Religious Communities of the Church of England. It currently has approximately 2,500 members who commit to seven promises, aspiring to live a lifestyle shaped by mission.

In 2010 CMS integrated with the South American Mission Society (SAMS).

The Church Mission Society Archive is housed at the University of Birmingham Special Collections.

Mission in Palestine and Egypt

The CMS made an important contribution to the Episcopal Church in Jerusalem and the Middle East. Former CMS missionary Samuel Gobat became the second bishop of the Diocese of Jerusalem, and in 1855 invited the CMS to make Palestine a mission field, which they did. Over the years many missionaries were sent, including John Zeller, who exercised a great influence on the development of Nazareth and Jerusalem and founded Christ Church, Nazareth, the first Protestant church in the Galilee, which was consecrated by Gobat in 1871.[38]

Another missionary was Frederick Augustus Klein, who served in Nazareth (1851-1877) and Egypt (1882), discovered the Moabite Stone, and assisted with the translation of the Book of Common Prayer into Arabic.[39][40][41][42]

J. Spencer Trimingham served with the CMS in the Sudan, Egypt, and West Africa (1937–53).

Mission in China

The Revd George Smith (later Bishop of Victoria, H.K.) and the Revd T. McClatchie established a mission at Shanghai in 1844.[20] The China mission was extended to Zhejiang (Cheh-kiang) Province at Ningbo (1848), Fujian Province (Fuh-Kien) at Fuzhou (Fuh-Chow) (May 1850), Hong Kong (1862), Guangdong (Kwan-tung) Province (1878) and Sichuan (Si-chuen Province) in south west China (1890).[20] The CMS remained active in Fuzhou and other places in China until the communist revolution in China in the 1950s.

St Stephen's Anglican Church was one of three churches founded in Hong Kong by the Church Missionary Society. It was led by Tsing-Shan Fok (霍靜山, 1851–1918, one of the earliest Chinese clergy in Hong Kong, starting in 1904.[43]

Mission in Kerala, India

The contribution made by the society in creating and maintaining educational institutions in Kerala, the most literate state in India, is significant. Many colleges and schools in Kerala and Tamil Nadu still have CMS in their names. The CMS College Kottayam may be one of the pioneers in popularising secondary education in southern India. (Former Indian President K. R. Narayanan is an alumnus.)

Benjamin Bailey was appointed to the Kottayam mission in the Indian state of Kerala. Benjamin Bailey translated the complete Bible to Malayalam language. He also athored the first printed Malayalam-English dictionary and the first Malayalam-English Dictionary. He is considered as the father of Malayalam Printing.[44]

The CMS continued to send missionaries to India, including Frank Lake in 1937. The successors of the protestant church missions are the Church of South India and the Church of North India.

Mission in New Zealand

History of the CMS mission in New Zealand

The Church Missionary Society sent missionaries to settle in New Zealand. The Revd Samuel Marsden[45] of the Church Missionary Society (chaplain in New South Wales), officiated at its first service on Christmas Day in 1814, at Oihi Bay in the Bay of Islands. The CMS founded its first mission at Rangihoua in the Bay of Islands in 1814 and over the next decade established farms and schools in the area. Thomas Kendall and William Hall were directed, in 1814, to proceed to the Bay of Islands in the Active, a vessel purchased by Marsden for the service of the mission, there to reopen communication with Ruatara, a local chief; an earlier attempt to establish a mission in the Bay of Islands had been delayed as a consequence of the Boyd Massacre in Whangaroa harbour in 1809.[46] Kendall and Hall left New South Wales on 14 March 1814 on the Active for an exploratory journey to the Bay of Islands. They met rangatira (chiefs) of the Ngāpuhi including Ruatara and the rising war-leader Hongi Hika; Hongi Hika and Ruatara travelled with Kendall when he returned to Australia on 22 August 1814. Kendall, Hall and John King, returned to the Bay of Islands on the Active on 22 December 1814 to establish the mission.[47]

In 1819 Marsden made his second visit to New Zealand, bringing with him John Butler as well as Francis Hall and James Kemp as lay settlers. William Puckey, a boatbuilder and carpenter, came with his family, including William Gilbert Puckey to assist in putting up the buildings at Kerikeri.[46] Butler and Kemp took charge of the Kerikeri mission, but proved unable to develop a harmonious working relationship. In 1820, Marsden paid his third visit, on H.M.S. Dromedary, bringing James Shepherd.[46] In 1823, Marsden paid his fourth visit, bringing with him Henry Williams and his wife Marianne as well as Richard Davis, a farmer, and William Fairburn, a carpenter, and their respective families.[46][48][49] In 1826 Henry's brother William and his wife Jane joined the CMS mission in New Zealand.

The mission schools provided religious education as well as English language practical skills. The first baptism occurred in 1825.[50] However the evangelical mission of the CMS achieved success only after the baptism of Ngapuhi chief Rawiri Taiwhanga in 1830. His example influenced others to be baptised into the Christian faith.[51] In 1833 a mission was established at Kaitaia in Northland as well as a mission at Puriri in the Thames area.[52] In 1835 missions were established in the Bay of Plenty and Waikato regions at Tauranga, Matamata and Rotorua and in 1836 a mission was open in the Manakau area.[47]

By 1840 William Williams had translated much of the New Testament into the Māori language. After 1844 Robert Maunsell worked with William Williams on the translation of the Bible.[53] The full translation of the Bible into the Māori language was completed in 1857.[54]

The CMS reached the height of its influence in New Zealand in the 1840s and 1850s. Missions covered almost the whole of the North Island and many Māori were baptised. The CMS in London began to reduce its commitment to the CMS mission in New Zealand in 1854 and only a handful of new missionaries arrived after this.

The CMS missionaries held the low church beliefs that were common among the 19th century Evangelical members of the Anglican Church. There was often a wide gap between the views of the CMS missionaries and the bishops and other clergy of the high church traditions of the Oxford Movement (also known as the Tractarians) as to the proper form of ritual and religious practice. Bishop Selwyn, who was appointed the first Anglican Bishop of New Zealand in 1841, held the high church (Tracharian) views although he appointed CMS missionaries to positions in the Anglican Church of New Zealand including appointing William Williams as the first Bishop of Waiapu.[55]

Notable CMS missionaries

Notable members of the CMS mission included:

- William Colenso arrived in December 1834 to work as a printer and missionary.[56] William and Elizabeth Fairburn Colenso worked at the mission station at Waitangi (Ahuriri, Napier) from 1844, until William Colenso was dismissed from the CMS in 1852.[57] Elizabeth continued to work for the CMS as a teacher. In the 1860’s she work on the manuscripts of the translation of the Bible into a Māori, including correcting proofs and suggesting alternative translations.[58][59]

- The Revd Octavius Hadfield arrived in December 1838 and was ordained a minister at Paihia on 6 January 1839,[47] and in November of that year he travelled to Otaki with Henry Williams, where he established a mission station.[60]

- Thomas Kendall arrived on the Active on 22 December 1814. He was dismissed from the CMS in August 1822.[47]

- The Revd Robert Maunsell arrived in 1835 and was sent to establishe the Manukau mission station at Port Waikato in the same year.[47] He later worked with William Williams on the translation of the Bible. Maunsell worked on the Old Testament, portions of which were published in 1840 with the full translation completed in 1857. He became a leading scholar of the Māori language.

- William Gilbert Puckey arrived with his parents William and Margery Puckey in 1919, then joined the CMS in 1821. He helped built, then served as the mate of the 55 foot schooner, the Herald.[47] He went to Sydney with his parents in 1826 then returned to the Bay of Islands the following year. He and Joseph Matthews established a mission station at Kaitaia in 1832/34.[52] As he had become fluent in the language since arriving as a boy of 14, he was a useful translator for the CMS mission, including collaborating with William Williams on the translation of the New Testament in 1837 and its revision in 1844.[47]

- The Revd Richard Taylor arrived in 1839.[61] He succeeded William Williams as principal of the Waimate Boys’ School in September 1839 and remained there into the 1840s.[62][63] The Revd Taylor moved to join the mission station at Whanganui in 1842.[47]

- The Revd Henry Williams and Marianne Williams arrived in the Bay of Islands in 1823. Henry Williams was appointed as the leader of the CMS mission in New Zealand.[64] In 1844, Williams was installed as Archdeacon of Waimate in the diocese centred on the Waimate Mission.[46]

- The Revd William Williams and Jane Williams arrived in the Bay of Islands in 1826.[65] William Williams led the CMS missionaries in translating the Bible into Māori and he also published an early dictionary and grammar of the Māori language. Williams was appointed Archdeacon of the East Cape diocese and later as the first Bishop of Waiapu.[55]

Formation of the New Zealand Church Missionary Society

In 1892 the New Zealand Church Missionary Association was formed in a Nelson church hall and the first New Zealand missionaries were sent to Japan soon after.[66] Funding from the UK stopped completely in 1903.[67] The association subsequent changed its name to the New Zealand Church Missionary Society (NZCMS) in 1916.[68]

In 2000 the NZCMS amalgamated with the South American Missionary Society of New Zealand.[66] The NZCMS works closely with the Anglican Missions Board, concentrating on mission work outside New Zealand and has been involved in Pakistan, East Africa, the Middle East, Cambodia, South Asia, South America and East Asia.[66]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 "The Church Missionary Atlas (Church Missionary Society)". Adam Matthew Digital. 1896. pp. 210–219. Retrieved 19 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "The Church Missionary Gleaner, February 1874". The Origin of the Church Missionary Society. Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 24 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Aston, Nigel. "Babington, Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/75363. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ "The Church Missionary Gleaner, August 1867". The Church Missionary Society (From the "American Church Missionary Register"). Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 24 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Mouser, Bruce (2004). "African academy 1799-1806". History of Education 33 (1).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "The Church Missionary Atlas (Church Missionary Society)". Adam Matthew Digital. 1896. pp. xi. Retrieved 19 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 3 4 "The Church Missionary Atlas (Christianity in Africa)". Adam Matthew Digital. 1896. pp. 23–64. Retrieved 19 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Marsden, Samuel. "The Marsden Collection". Marsden Online Archive. University of Otago. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- 1 2 "The Church Missionary Atlas (New Zealand)". Adam Matthew Digital. 1896. pp. 210–219. Retrieved 19 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 3 "The Church Missionary Atlas (India)". Adam Matthew Digital. 1896. pp. 95–156. Retrieved 19 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "The Church Missionary Atlas (Ceylon)". Adam Matthew Digital. 1896. pp. 163–168. Retrieved 19 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "The Church Missionary Gleaner, March 1857". Missionary Work Around the Winnepegoosis Lake, Rupert's Land. Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 24 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 3 4 "The Church Missionary Atlas (Canada)". Adam Matthew Digital. 1896. pp. 220–226. Retrieved 19 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "The Church Missionary Gleaner, September 1877". The Red Indians of the Saskatchewan. Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 24 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "The Church Missionary Gleaner, December 1853". The Eskimos (part 1). Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 23 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "The Church Missionary Gleaner, December 1854". The Eskimos (part 2). Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 23 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "The Church Missionary Gleaner, June 1877". The First Missionary to the Eskimos. Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 24 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 3 4 "The Church Missionary Atlas (Middle East)". Adam Matthew Digital. 1896. pp. 67–76. Retrieved 19 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Donald Crummey, Priests and Politicians, 1972, Oxford University Press (reprinted Hollywood: Tsehai, 2007), pp. 12, 29f. For an account of the society's Amharic translation, see Edward Ullendorff, Ethiopia and the Bible (Oxford: University Press for the British Academy, 1968), pp. 62–67 and the sources cited there.

- 1 2 3 "The Church Missionary Atlas (China)". Adam Matthew Digital. 1896. pp. 179–196. Retrieved 19 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "The Church Missionary Atlas (Mauritius)". Adam Matthew Digital. 1896. pp. 157–159. Retrieved 19 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 3 "The Church Missionary Atlas (British Columbia)". Adam Matthew Digital. 1896. pp. 227–232. Retrieved 19 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "The Church Missionary Gleaner, March 1861". First Letter from a New Missionary to British Columbia. Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 24 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "The Church Missionary Atlas (Madagascar)". Adam Matthew Digital. 1896. p. 160. Retrieved 19 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "The Church Missionary Gleaner, September 1874". C.M.S. Missionaries in Japan. Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 24 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "The Church Missionary Gleaner, December 1874". Our Missionaries in Japan. Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 24 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "The Church Missionary Gleaner, May 1877". The Ainos of Japan. Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 24 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "The Church Missionary Atlas (Japan)". Adam Matthew Digital. 1896. pp. 205–2009. Retrieved 19 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "The Church Missionary Gleaner, January 1875". Appointment of Rev. H. Maundrell to Japan. Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 24 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "The Church Missionary Gleaner, May 1876". The New Mission to Persia. Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 24 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "The Church Missionary Gleaner, February 1877". From London to Ispahan. Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 24 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "The Church Missionary Atlas (Persia)". Adam Matthew Digital. 1896. pp. 78–80. Retrieved 19 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "The Church Missionary Gleaner". Church Missionary Society (1841-1857). Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 18 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Missionary Periodicals Database (Yale University)

- ↑ Stock 1923.

The more liberal CMS position may be compared with the attitude expressed in the preface to its 1904 English–Kikuyu Vocabulary, whose author, CMS member A. W. McGregor, complained of the difficulty in obtaining information about Kikuyu from "very unwilling and unintelligent natives" (McGregor 1904, p. iii). - ↑ CMS: Annual Review 2009–10 (PDF).

- ↑ Crowther Centre for Mission Education

- ↑ Miller, Duane Alexander (October 2012). "Christ Church (Anglican) in Nazareth: a brief history with photographs" (PDF). St Francis Magazine 8 (5).

- ↑ Murray, Jocelyn (1985). Proclaim the Good News: A Short History of the Church Missionary Society.

- ↑ Stock, Eugene (1899). History of the Church Missionary Society.

- ↑ "Frederick Augustus Klein". Dictionary of African Christian Biography. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ↑ Anderson, Gerald (1998). Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

- ↑ Rebecca Chan Chung, Deborah Chung and Cecilia Ng Wong, "Piloted to Serve", 2012.

- ↑ Benjamin Bailiyum Malayala Saahityavum. By Dr. Babu Cherian. Published by the Department of Printing and Publishing, Mahatma Gandhi University, Kottayam.

- ↑ Marsden, Samuel. "The Marsden Collection". Marsden Online Archive. University of Otago. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Carleton, Hugh (1874). "Vol. I". The Life of Henry Williams. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Rogers, Lawrence M. (1973). Te Wiremu: A Biography of Henry Williams. Pegasus Press.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, Caroline (2011). Te Wiremu: Henry Williams – Early Years in the North. Huia Publishers, New Zealand. ISBN 978-1-86969-439-5.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, Caroline (2004). Marianne Williams: Letters from the Bay of Islands. Penguin Books, New Zealand. ISBN 0-14-301929-5.

- ↑ "The Church Missionary Gleaner, April 1874". The New Zealand Mission. Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 24 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Dench, Alison, Essential Dates: A timeline of New Zealand history, Random House, 2005

- 1 2 Williams, Frederic Wanklyn. "Through Ninety Years, 1826–1916: Life and Work Among the Maoris in New Zealand: Notes of the Lives of William and William Leonard Williams, First and Third Bishops of Waiapu (Chapter 3)". Early New Zealand Books (NZETC).

- ↑ Williams, William (1974). The Turanga journals, 1840–1850. F. Porter (Ed). p. 44.

- ↑ Transcribed by Terry Brown Bishop of Malaita, Church of the Province of Melanesia, 2008 (10 November 1858). "Untitled article on Maori Bible translation". The Church Journal, New-York. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- 1 2 Williams, William (1974). The Turanga journals, 1840–1850. F. Porter (Ed) Wellington,. p. 37.

- ↑ Colenso, William (1890). The Authentic and Genuine History of the Signing of the Treaty of Waitangi. Wellington: By Authority of George Didsbury, Government Printer. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- ↑ Mackay, David (30 October 2012). "Colenso, William". Dictionary of New Zealand biography. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- ↑ Transcribed by the Right Reverend Dr. Terry Brown (2007). "ELIZABETH COLENSO Her work for the Melanesian Mission By her eldest granddaughter Francis Edith Swabey 1956". Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- ↑ Murray, Janet E. (30 October 2012). "Colenso, Elizabeth". Dictionary of New Zealand biography. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ↑ "The Church Missionary Gleaner, March 1842". Remarkable Introduction and Rapid Extension of the Gospel in the Neighbourhood of Cook's Straits. Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 10 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "The Church Missionary Gleaner, April 1874". The Late Rev. R. Taylor. Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 24 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Williams, William (1974). The Turanga journals, 1840–1850. F. Porter (Ed). pp. 32 & 67.

- ↑ "The Church Missionary Gleaner, March 1844". A Native Congregation at Waimate – Contrast between the Past and the Present. Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 13 October 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Carleton, Hugh (1874). "Vol. I". The Life of Henry Williams. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, Caroline (2004). Marianne Williams: Letters from the Bay of Islands. Penguin Books, New Zealand. p. 103. ISBN 0-14-301929-5.

- 1 2 3 "NZCMS". New Zealand Church Missionary Society. Retrieved 18 July 2008.

- ↑ "Church Missionary Society". Te Ara. Retrieved 18 July 2008.

- ↑ Maina, Steve (25 June 2009). "Response to Michael Blain's article published in AMB- E Newsletter - May 09". A Glimpse of New Zealand as it Was. The Anglican Missions Board of the Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand and Polynesia. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

Bibliography

CMS in New Zealand:

- Carlton, Hugh (1874). "The Life of Henry Williams, Volumes 1 & 2". Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- (English) Fitzgerald, Caroline (2004) – Letters from the Bay of Islands, Sutton Publishing Limited, United Kingdom; ISBN 0-7509-3696-7 (Hardcover). Penguin Books, New Zealand, (Paperback) ISBN 0-14-301929-5

- (English) Fitzgerald, Caroline (2011) - Te Wiremu – Henry Williams: Early Years in the North, Huia Press, New Zealand, (Paperback) ISBN 978-1-86969-439-5

CMS – general:

- Hewitt, Gordon, The Problems of Success, A History of the Church Missionary Society 1910–1942, Vol I (1971) In Tropical Africa. The Middle East. At Home ISBN 0-334-00252-4; Vol II (1977)Asia Overseas Partners ISBN 0-334-01313-5

- McGregor, A. W. (1904). English–Kikuyu Vocabulary. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

- Murray, Jocelyn (1985). Proclaim the Good News. A Short History of the Church Missionary Society. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-34501-2..

- Stock, Eugene (1899–1916). "The History of the Church Missionary Society: Its Environment, Its Men, and Its Work" 1–4. London: CMS.

- Stock, Eugene (1923). "The Recent Controversy in the C.M.S." (Reprinted from the Church Missionary Review ed.). London: CMS..

- Missionary Register; containing an abstract of the principal missionary and bible societies throughout the world. From 1816, containing the principal transactions of the various institutions for propagating the gospel with the proceedings at large of the Church Missionary Society.

- Published from 1813–1855 by L. B. Seeley & Sons, London

- Some are online readable and downloadable at Google Books:

External links

- CMS Britain

- CMS Australia

- New Zealand CMS

- CMS Ireland

- World Mission News from CMS

- CMS mission videos

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||