The Man with the Golden Gun (film)

| The Man with the Golden Gun | |

|---|---|

British cinema poster for The Man with the Golden Gun, designed by Robert McGinnis | |

| Directed by | Guy Hamilton |

| Produced by |

Albert R. Broccoli Harry Saltzman |

| Screenplay by |

Richard Maibaum Tom Mankiewicz |

| Based on |

The Man with the Golden Gun by Ian Fleming |

| Starring |

Roger Moore Christopher Lee Britt Ekland |

| Music by | John Barry |

| Cinematography |

Ted Moore Oswald Morris |

| Edited by |

Raymond Poulton John Shirley |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 125 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $7 million |

| Box office | $97.6 million |

The Man with the Golden Gun is a 1974 British spy film, the ninth entry in the James Bond series and the second to star Roger Moore as the fictional MI6 agent James Bond. A loose adaptation of Ian Fleming's novel of same name, the film has Bond sent after the Solex Agitator, a device that can harness the power of the sun, while facing the assassin Francisco Scaramanga, the "Man with the Golden Gun". The action culminates in a duel between them that settles the fate of the Solex.

The Man with the Golden Gun was the fourth and final film in the series directed by Guy Hamilton. The script was written by Richard Maibaum and Tom Mankiewicz. The film was set in the face of the 1973 energy crisis, a dominant theme in the script—Britain had still not yet fully overcome the crisis when the film was released in December 1974. The film also reflects the then-popular martial arts film craze, with several kung fu scenes and a predominantly Asian location, being shot in Thailand, Hong Kong, and Macau. Part of the film is also set in Beirut, Lebanon, making it the first Bond film to include a Middle Eastern location.

The film saw mixed reviews, with Christopher Lee's performance as Scaramanga, intended to be a villain of similar skill and ability to Bond, being praised; but reviewers criticised the film as a whole, particularly the comedic approach, and some critics described it as the lowest point in the canon. Although the film was profitable, it is the fourth-lowest-grossing Bond film in the series. It was also the final film to be co-produced by Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman, with Saltzman selling his 50% stake in Danjaq, LLC, the parent company of Eon Productions, after the release of the film.

Plot

In London, a golden bullet with James Bond's code "007" etched into its surface is received by MI6. It is believed that it was sent by famed assassin Francisco Scaramanga, who uses a golden gun, to intimidate the agent. Because of the perceived threat to the agent's life, M relieves Bond of a mission revolving around the work of a scientist named Gibson, thought to be in possession of information crucial to solving the energy crisis with solar power. Bond sets out unofficially to find Scaramanga.

After retrieving a spent golden bullet from a belly dancer in Beirut and tracking its manufacturer to Macau, Bond sees Andrea Anders, Scaramanga's mistress, collecting the shipment of golden bullets at a casino. Bond follows her to Hong Kong and in her Peninsula Hotel room pressures her to tell him about Scaramanga, his appearance and his plans; she directs him to the Bottoms Up Club. The club proves to be the location of Scaramanga's next 'hit', Gibson, from whom Scaramanga's dwarf henchman Nick Nack steals the "Solex agitator", a key component of a solar power station. Before Bond can assert his innocence, however, Lieutenant Hip escorts him away from the scene, taking him to meet M and Q in a hidden headquarters in the wreck of the RMS Queen Elizabeth in the harbour. M assigns 007 to retrieve the Solex agitator and assassinate Scaramanga.

Bond then travels to Bangkok to meet Hai Fat, a wealthy Thai entrepreneur suspected of arranging Gibson's murder. Bond poses as Scaramanga, but his plan backfires because Scaramanga himself is being hosted at Hai Fat's estate. Bond is captured and placed in Fat's dojo, where the fighters are instructed to kill him. After escaping with the aid of Hip and his nieces, Bond speeds away on a long tail boat along the river and reunites with his British assistant Mary Goodnight. Scaramanga subsequently kills Hai Fat and usurps control of his enterprise, and takes the Solex.

Anders visits Bond, revealing that she had sent the bullet to London and wants Bond to kill Scaramanga. In payment, she promises to hand the Solex over to him at a Muay Thai venue the next day. At the match, Bond discovers Anders dead and meets Scaramanga. Bond spots the Solex on the floor and is able to smuggle it away to Hip, who passes it to Goodnight. Attempting to place a homing device on Scaramanga's car, she is locked into the vehicle's boot. Bond sees Scaramanga driving away and steals a showroom car to give chase, coincidentally with Sheriff J.W. Pepper seated within it. Bond and Pepper follow Scaramanga in a car chase across Bangkok, which concludes when Scaramanga's car transforms into a plane, which flies him, Nick Nack and Goodnight to his private island.

Picking up Goodnight's tracking device, Bond flies a seaplane into Red Chinese waters and lands at Scaramanga's island. Scaramanga welcomes Bond and shows him the high-tech solar power plant he has taken over, the technology for which he intends to sell to the highest bidder. While demonstrating the equipment, Scaramanga uses a powerful solar beam to destroy Bond's plane.

Scaramanga then proposes a pistol duel with Bond on the beach; the two men stand back to back and are instructed by Nick Nack to take twenty paces, but when Bond turns and fires, Scaramanga has vanished. Nick Nack leads Bond into Scaramanga's Funhouse where Bond stands in the place of a mannequin of himself; when Scaramanga walks by, Bond takes him by surprise and kills him. Goodnight, in waylaying one of Scaramanga's henchman who falls into a pool of liquid helium, upsets the balance of the solar plant, which begins to go out of control. Bond retrieves the Solex unit just before the island explodes, and they escape unharmed in Scaramanga's Chinese junk. Bond then fends off a final attack by Nick Nack, who had smuggled himself aboard, subduing him.

Cast

- Roger Moore as James Bond: An MI6 agent who receives a golden bullet, supposedly from Scaramanga, indicating that he is a target of Scaramanga.

- Christopher Lee as Francisco Scaramanga: The main villain and assassin who is identified by his use of a golden gun; he also has a 'superfluous papilla', or supernumerary nipple. Scaramanga plans to misuse solar energy for destructive purposes. Lee was Ian Fleming's step-cousin[1] and regular golf partner.[2] Scaramanga has been called "the best-characterised Bond villain yet."[3]

- Britt Ekland as Mary Goodnight: Bond's assistant. Described by the critic of the The Sunday Mirror as being "an astoundingly stupid blonde British agent".[4] Ekland had previously been married to Peter Sellers, who appeared in the 1967 Bond film, Casino Royale.[5]

- Maud Adams as Andrea Anders: Scaramanga's mistress. Adams described the role as "a woman without a lot of choices: she's under the influence of this very rich, strong man, and is fearing for her life most of the time; and when she actually rebels against him and defects is a major step."[6] The Man with the Golden Gun was the first of three Bond films in which Maud Adams appeared; in 1983, she played a different character, Octopussy, in the film of the same name. She would also later have a cameo as an extra in Roger Moore's last Bond film, A View to a Kill.[7]

- Hervé Villechaize as Nick Nack: Scaramanga's dwarf manservant and accomplice. Villechaize was later known to television audiences as Tattoo, in the series Fantasy Island.

- Richard Loo as Hai Fat: A Thai millionaire industrialist who was employing Scaramanga to assassinate the inventor of the "Solex" (a revolutionary solar energy device) and steal the device.

- Soon-Tek Oh as Lieutenant Hip: Bond's local contact in Hong Kong and Bangkok. Soon-Tek Oh trained in martial arts for the role,[8] and his voice was partially dubbed over.[9]

- Clifton James as Sheriff J.W. Pepper: A Louisiana sheriff who happens to be on holiday in Thailand. Hamilton liked Pepper in the previous film, Live and Let Die, and asked Mankewicz to write him into The Man with the Golden Gun as well.[10] Pepper's inclusion has been seen as one of "several ill-advised lurches into comedy" in the film.[1]

- Bernard Lee as M: The head of MI6.

- Marc Lawrence as Rodney: An American gangster who attempts to outshoot Scaramanga in his funhouse. Lawrence also appeared in Diamonds Are Forever.[11]

- Desmond Llewelyn as Q: The head of MI6's technical department.

- Marne Maitland as Lazar: A gunsmith based in Macau who manufactures golden bullets for Scaramanga.

- Lois Maxwell as Miss Moneypenny.

- James Cossins as Colthorpe: An MI6 armaments expert who identifies the maker of Scaramanga's golden bullets. The first draft of the script originally called the role Boothroyd until it was realised that was also Q's name and it was subsequently changed.[12]

- Carmen du Sautoy as Saida: A Beirut belly dancer. Saida was originally written as overweight and wearing excessive make-up, but the producers decided to cast a woman closer to the classic Bond girl.[13]

Production

Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman intended to follow You Only Live Twice with The Man with the Golden Gun, inviting Roger Moore to the Bond role. However, filming was planned in Cambodia, and the Samlaut Uprising made filming impractical, leading to the production being cancelled.[14] On Her Majesty's Secret Service was produced instead with George Lazenby as Bond. Lazenby's next Bond film, Saltzman told a reporter, would be either The Man with the Golden Gun or Diamonds Are Forever. The producers chose the latter title, with Sean Connery returning as Bond.[15]

Broccoli and Saltzman then decided to start production on The Man with the Golden Gun after Live and Let Die.[16] This was the final Bond film to be co-produced by Saltzman as his partnership with Broccoli was dissolved after the film's release. Saltzman sold his 50% stake in Eon Productions's parent company, Danjaq, LLC, to United Artists to alleviate his financial problems.[17] The resulting legalities over the Bond property delayed production of the next Bond film, The Spy Who Loved Me, for three years.[18]

The novel is mostly set in Jamaica, a location which had been already used in the earlier films, Dr. No and Live and Let Die; The Man with the Golden Gun saw a change in location to put Bond in the Far East for the second time.[19] After considering Beirut, where part of the film is set,[20] Iran, where the location scouting was done but eventually discarded because of the Yom Kippur War,[21] and the Hạ Long Bay in Vietnam, the production team chose Thailand as a primary location, following a suggestion of production designer Peter Murton after he saw pictures of the Phuket bay in a magazine.[16] Saltzman was happy with the choice of the Far East for the setting as he had always wanted to go on location in Thailand and Hong Kong.[22] During the reconnaissance of locations in Hong Kong, Broccoli saw the wreckage of the former RMS Queen Elizabeth and came up with the idea of using it as the base for MI6's Far East operations.[20]

Writing and themes

Tom Mankiewicz wrote a first draft for the script in 1973, delivering a script that was a battle of wills between Bond and Scaramanga, who he saw as Bond's alter ego, "a super-villain of the stature of Bond himself."[23] Tensions between Mankiewicz and Guy Hamilton[24] and Mankiewicz's growing sense that he was "feeling really tapped out on Bond" led to the re-introduction of Richard Maibaum as the Bond screenwriter.[25]

Maibaum, who had worked on six Bond films previously, delivered his own draft based on Mankiewicz's work.[16] Much of the plot involving Scaramanga being Bond's equal was sidelined in later drafts.[26] For one of the two main aspects of the plot, the screenwriters used the 1973 energy crisis as a backdrop to the film,[27] allowing the MacGuffin of the "Solex agitator" to be introduced; Broccoli's stepson Michael G. Wilson researched solar power to create the Solex.[16]

While Live and Let Die had borrowed heavily from the blaxploitation genre,[28] The Man with the Golden Gun borrowed from the martial arts genre[29] that was popular in the 1970s through films such as Fist of Fury (1972) and Enter the Dragon (1973).[30] However, the use of the martial arts for a fight scene in the film "lapses into incredibility" when Lt Hip and his two nieces defeat an entire dojo.[23]

Casting

Originally, the role of Scaramanga was offered to Jack Palance, but he turned the opportunity down.[31] Christopher Lee, who was eventually chosen to portray Scaramanga, was Ian Fleming's step-cousin and Fleming had suggested Lee for the role of Dr. Julius No in the 1962 series opener Dr. No. Lee noted that Fleming was a forgetful man and by the time he mentioned this to Broccoli and Saltzman they had cast Joseph Wiseman in the part.[32] Due to filming on location in Bangkok, his role in the film affected Lee's work the following year, as director Ken Russell was unable to sign Lee to play Specialist in the 1975 film Tommy, a part eventually given to Jack Nicholson.[33]

Two Swedish models were cast as the Bond girls, Britt Ekland and Maud Adams. Ekland had been interested in playing a Bond girl since she had seen Dr. No, and contacted the producers about the main role of Mary Goodnight.[16] Hamilton met Adams in New York, and cast her because "she was elegant and beautiful that it seemed to me she was the perfect Bond girl".[10] When Ekland read the news that Adams had been cast for The Man with the Golden Gun, she became upset, thinking Adams had been selected to play Goodnight. Broccoli then called Ekland to invite her for the main role,[16] as after seeing her in a film, Broccoli thought Ekland's "generous looks" made her a good contrast to Adams.[10] Hamilton decided to put Marc Lawrence, whom he had worked with on Diamonds Are Forever, to play a gangster shot dead by Scaramanga at the start of the film, because he found it an interesting idea to "put sort of a Chicago gangster in the middle of Thailand".[10]

Filming

Filming commenced on 6 November 1973 at the partly submerged wreck of the RMS Queen Elizabeth, which acted as a top-secret MI6 base grounded in Victoria Harbour in Hong Kong.[34] The crew was small, and a stunt double was used for James Bond. Other Hong Kong locations included the Hong Kong Dragon Garden as the estate of Hai Fat, which portrayed a location in Bangkok.[35] The major part of principal photography started on 18 April 1974 in Thailand.[16][36] Thai locations included Bangkok, Thon Buri, Phuket and the nearby Phang Nga Province, on the islands of Ko Khao Phing Kan (Thai: เกาะเขาพิงกัน) and Ko Tapu (Thai: เกาะตะปู).[37][20] Scaramanga's hideout is on Ko Khao Phing Kan, and Ko Tapu is often now referred to as James Bond Island both by locals and in tourist guidebooks.[38] The scene during the boxing match used an actual Muay Thai fixture at the Lumpinee Boxing Stadium.[20]

"[A] car chase [in Bangkok occurred] near a [canal or] khlong on Krung Kasem Road".[39]

In late April, production returned to Hong Kong, and also shot in Macau,[16] as the island is famous for its casinos, which Hong Kong does not have.[13] As some scenes in Thailand had to be finished, and also production had to move to studio work in Pinewood Studios—which included sets such as Scaramanga's solar energy plant and island interior— Academy Award winner Oswald Morris was hired to finish the job after cinematographer Ted Moore became ill.[40] Morris was initially reluctant, as he did not like his previous experiences taking over other cinematographers' work, but accepted after dining with Broccoli.[41] Production wrapped in Pinewood in August 1974.[13]

One of the main stunts in the film consisted of stunt driver "Bumps" Willard (as James Bond) driving an AMC Hornet leaping a broken bridge and spinning around 360 degrees in mid-air about the longitudinal axis, doing an "aerial twist"; Willard successfully completed the jump on the first take.[37] The stunt was shown in slow motion as the scene was too fast.[42] Composer John Barry added a slide whistle sound effect over the stunt, which Broccoli kept in despite thinking that it "undercouped the stunt". Barry later regretted his decision, thinking the whistle "broke the golden rule" as the stunt was "for what it was all worth, a truly dangerous moment, ... true James Bond style".[43] The sound effect was described as "simply crass",[42] with one writer, Jim Smith, suggesting that the stunt "brings into focus the lack of excitement in the rest of the film and is spoilt by the use of 'comedy' sound effects."[19] Eon Productions had licensed the stunt, which had been designed by Raymond McHenry;[20] the stunt was initially conceived at Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory (CAL) in Buffalo, New York as a test for their powerful vehicle simulation software. After development in simulation, ramps were built and the stunt was tested at CAL's proving ground.[44] It toured as part of the All American Thrill Show as the Astro Spiral before it was picked up for the film. The television programme Top Gear attempted to repeat the stunt in June 2008, but failed.[45] The scene where Scaramanga's car flies was done at Bovington Camp, with a model inspired by an actual car plane prototype.[16] Bond's duel with Scaramanga, which Mankewicz said was inspired by the climactic faceoff in Shane, had its length shortened as the producers felt it was causing pacing problems. The trailers featured some of the cut scenes.[13]

Hamilton adapted an idea of his involving Bond in Disneyland for Scaramanga's funhouse. The funhouse was designed to be a place where Scaramanga could get the upper hand by distracting the adversary with obstacles,[10] and was described by Murton as a "melting pot of ideas" which made it "both a funhouse and a horror house".[46] While an actual wax figure of Roger Moore was used, Moore's stunt double Les Crawford was the cowboy figure, and Ray Marione played the Al Capone figure. The canted sets such as the funhouse and the Queen Elizabeth had inspiration from German Expressionism films such as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.[13] For Scaramanga's solar power plant, Hamilton used both the Pinewood set and a miniature projected by Derek Meddings, often cutting between each other to show there was no discernible difference.[10] The destruction of the facility was a combination of practical effects on the set and a destruction of the miniature.[16] Meddings based the island blowing up on footage of the Battle of Monte Cassino.[47]

Golden Gun prop

Three Golden Gun props were made; a solid piece, one that could be fired with a cap and one that could be assembled and disassembled, although Christopher Lee said that the process "was extremely difficult."[32] The gun was "one of the more memorable props in the Bond series"[34] and consisted of an interlocking fountain pen (the barrel), cigarette lighter (the bullet chamber), cigarette case (the handle) and cufflink (the trigger) with the bullet secured in Scaramanga's belt buckle.[48] The gun was to take a single 23-carat gold bullet produced by the Macau-based gunsmith, Lazar.[49] The Golden Gun ranked sixth in a 2008 20th Century Fox poll of the most popular film weapons, which surveyed approximately 2,000 film fans.[50]

On 10 October 2008, it was discovered that one of the golden guns used in the film, which is estimated to be worth around £80,000, was missing (suspected stolen) from Elstree Props, a company based at Hertfordshire studios.[51]

Music

Tony Bramwell, who worked for Harry Saltzman's music-publishing company "Hilary Music", wanted Elton John or Cat Stevens to sing the title song. However, by this time the producers were taking turns producing the films; Albert Broccoli - whose turn it was to produce - rejected Bramwell's suggestions. Bramwell subsequently dismissed the Barry-Lulu tune as "mundane".[52]

The theme tune to The Man with the Golden Gun, released in 1974, was performed by Scottish singer Lulu and composed by John Barry. The lyrics to the song were written by Don Black and have been described variously as "ludicrous",[48] "inane"[23] and "one long stream of smut", because of its sexual innuendo.[53] Alice Cooper wrote a song titled "Man with the Golden Gun" to be used by the producers of the film, but they opted for Lulu's song instead. Cooper released his song in his album Muscle of Love.[54]

Barry had only three weeks to score The Man with the Golden Gun[55] and the theme tune and score are generally considered by critics to be among the weakest of Barry's contributions to the series—an opinion shared by Barry himself: "It's the one I hate most ... it just never happened for me."[56] The Man with the Golden Gun was also the first to drop the distinctive plucked guitar from the theme heard over the gun barrel opening. A sample from one of the songs, "Hip's Trip", was used by The Prodigy in the "Mindfields" track on the album The Fat of the Land.[57]

Release and reception

The Man with the Golden Gun was premiered at the Odeon Leicester Square in London on 19 December 1974,[58] with general release in the United Kingdom the same day. The film was made with an estimated budget of $7 million; despite initial good returns from the box office,[59] The Man with the Golden Gun grossed a total of $97.6 million at the worldwide box office,[60] with $21 million earned in the USA, making it the fourth lowest-grossing Bond film in the series.[61]

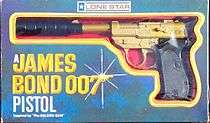

The promotion of the film had "one of the more anaemic advertising campaigns of the series"[48] and there were few products available, apart from the soundtrack and paperback book, although Lone Star Toys produced a "James Bond 007 pistol" in gold; this differed from the weapon used by Scaramanga in the film as it was little more than a Walther P38 with a silencer fitted.[62]

Contemporary reviews

The Man with the Golden Gun met with mixed reviews upon its release. Derek Malcolm in The Guardian savaged the film, saying that "the script is the limpest of the lot and ... Roger Moore as 007 is the last man on earth to make it sound better than it is."[63] There was some praise from Malcolm, although it was muted, saying that "Christopher Lee ... makes a goodish villain and Britt Ekland a passable Mary Goodnight ... Up to scratch in production values ... the film is otherwise merely a potboiler. Maybe enough's enough."[63] Tom Milne, writing in The Guardian's sister paper, The Observer was even more caustic, writing that "This series, which has been scraping the bottom of the barrel for some time, is now through the bottom ... with depressing borrowings from Hong Kong kung fu movies, not to mention even more depressing echoes of the 'Carry On' smut."[64] He summed up the film by saying it was "sadly lacking in wit or imagination."[64]

David Robinson, the film critic at The Times dismissed the film and Moore's performance, saying that Moore was "substituting non-acting for Connery's throwaway", while Britt Ekland was "his beautiful, idiot side-kick ... the least appealing of the Bond heroines."[65] Robinson was equally damning of the changes in the production crew, observing that Ken Adam, an "attraction of the early Bond films," had been "replaced by decorators of competence but little of his flair."[65] The writers "get progressively more naive in their creation of a suburban dream of epicureanism and adventure."[65] Writing for The New York Times, Nora Sayre considered the film to suffer from "poverty of invention and excitement", criticizing the writing and Moore's performance and finding Villechaize and Lee as the only positive points for their "sinister vitality that cuts through the narrative dough."[66]

The Sunday Mirror critic observed that The Man with the Golden Gun "isn't the best Bond ever" but found it "remarkable that Messrs. Saltzman and Broccoli can still produce such slick and inventive entertainment".[4] Arthur Thirkwell, writing in the Sunday Mirror's sister paper, the Daily Mirror concentrated more on lead actor Roger Moore than the film itself: "What Sean Connery used to achieve with a touch of sardonic sadism, Roger Moore conveys with roguish schoolboy charm and the odd, dry quip."[67] Thirkwell also said that Moore "manages to make even this reduced-voltage Bond a character with plenty of sparkle."[67] Judith Crist of New York Magazine gave a positive review, saying "the scenery's grand, the lines nice and the gadgetry entertaining", also describing the production as a film that "capture[s] the free-wheeling, whooshing non-sense of early Fleming's fairy tale for grown-ups orientation".[68]

Jay Cocks, writing in Time, focused on gadgets such as Scaramanga's flying car, as what is wrong with both The Man with the Golden Gun and the more recent films in the Bond series, calling them "Overtricky, uninspired, these exercises show the strain of stretching fantasy well past wit."[69] Cocks also criticised the actors, saying that Moore "lacks all Connery's strengths and has several deep deficiencies", while Lee was "an unusually unimpressive villain".[69]

Reflective reviews

Opinion on The Man with the Golden Gun has not changed with the passing of time: as of November 2015, the film holds a 45% rating from Rotten Tomatoes,[70] while Ian Freer of Empire found the film "an entertaining 007 adventure, something that tonally, if not qualitatively, could happily sit within the Connery era."[71] IGN chose The Man with the Golden Gun as the worst Bond film, claiming it "has a great concept ... but the execution is sloppy and silly",[72] and Entertainment Weekly chose it as the fourth worst, saying that the "plot is almost as puny as the sidekick".[73] On the other hand, Norman Wilner of MSN chose it as the tenth best, with much praise for Christopher Lee's performance.[74]

Some critics saw the film as uninspired, tired and boring.[75] Roger Moore was also criticised for playing Bond against type, in a style more reminiscent of Sean Connery, although Lee's performance received acclaim. Danny Peary wrote that The Man with the Golden Gun "lacks invention ... is one of the least interesting Bond films" and "a very laboured movie, with Bond a stiff bore, Adams and Britt Ekland uninspired leading ladies".[76] Peary believes that the shootout between Bond and Scaramanga in the funhouse "is the one good scene in the movie, and even it has an unsatisfying finish" and also bemoaned the presence of Clifton James, "unfortunately reprising his unfunny redneck sheriff from Live and Let Die."[76]

Chris Nashawaty of Entertainment Weekly argues that Scaramanga is the best villain of the Roger Moore James Bond films,[77] while listing Mary Goodnight among the worst Bond girls, saying that "Ekland may have had one of the series' best bikinis, but her dopey, doltish portrayal was a turnoff as much to filmgoers as to fans of Ian Fleming's novels".[78] The Times put Scaramanga as the fifth best Bond villain in their list,[79] and Ekland was the third in their list of the top 10 most fashionable Bond girls.[80] Maxim listed Goodnight at fourth in their Top Bond Babes list, saying that "Agent Goodnight is the clumsiest spy alive. But who cares as long as she's using her perfect bikini bottom to muck things up?"[81]

See also

References

- 1 2 Brooke, Michael. "The Man with the Golden Gun (1974)". BFI Screenonline. The British Film Institute. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ↑ Higgins, John (12 December 1974). "From scaremonger to Scaramanga". The Times.

- ↑ Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 118.

- 1 2 "Amazing, Mr Bond, but you're still a winner". Sunday Mirror. 22 December 1974.

- ↑ Smith 2002, p. 134.

- ↑ Maud Adams. The Man with the Golden Gun audio commentary. The Man with the Golden Gun Ultimate Edition, Disk 1: MGM Home Entertainment.

- ↑ Maud Adams. Inside A View to a Kill (VCD/DVD). MGM Home Entertainment Inc.

- ↑ Double-O Stuntmen. The Man with the Golden Gun Ultimate Edition, Disk 2: MGM Home Entertainment.

- ↑ Soon-Tek Oh. The Man with the Golden Gun audio commentary. The Man with the Golden Gun Ultimate Edition, Disk 1: MGM Home Entertainment.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Guy Hamilton. The Man with the Golden Gun audio commentary. The Man with the Golden Gun Ultimate Edition, Disk 1: MGM Home Entertainment.

- ↑ "Diamonds Are Forever (1971)". BFI Screenonline. British Film Institute. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- ↑ Smith 2002, p. 131.

- 1 2 3 4 5 David Naylor. The Man with the Golden Gun audio commentary. The Man with the Golden Gun Ultimate Edition, Disk 1: MGM Home Entertainment.

- ↑ Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 82.

- ↑ Graham, Sheilah (5 June 1969). "Speaking For Myself: Film Maker Saltzman Also Restaurateur" (PDF). Watertown Daily Times. p. 9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Inside The Man with the Golden Gun (NTSC, Widescreen, Closed-captioned) (DVD). The Man with the Golden Gun Ultimate Edition, Disc 2: MGM/UA Home Video. 2000.

- ↑ Smith 2002, p. 141-2.

- ↑ Inside The Spy Who Loved Me (NTSC, Widescreen, Closed-captioned) (DVD). The Spy Who Loved Me Ultimate Edition, Disc 2: MGM/UA Home Video. 2000.

- 1 2 Smith 2002, p. 136.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cork & Stutz 2007, p. 286.

- ↑ Tom Mankewicz. The Man with the Golden Gun audio commentary. The Man with the Golden Gun Ultimate Edition, Disk 1: MGM Home Entertainment.

- ↑ Benson 1988, p. 211.

- 1 2 3 Benson 1988, p. 215.

- ↑ Smith 2002, p. 137.

- ↑ Mankiewicz & Crane 2012, p. 162.

- ↑ Smith 2002, p. 138.

- ↑ Black 2004, p. 78.

- ↑ Benshoff, Harry M (Winter 2000). "Blaxploitation Horror Films: Generic Reappropriation or Reinscription?". Cinema Journal 39 (2): 37. doi:10.1353/cj.2000.0001.

- ↑ Smith 2002, p. 140.

- ↑ Fu & Desser 2000, p. 26

- ↑ Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 113.

- 1 2 "Christopher Lee: The legendary actor on Scaramanga, Fleming and playing pure evil". Empire. 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- ↑ Miller, Frank. "Tommy". Turner Classic Movies. Turner Entertainment Networks, Inc. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- 1 2 Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 114.

- ↑ "Public pleasure, private ownership?". Christopher DeWolf. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- ↑ "United Artists". Film Bulletin. 43-44: 48. 1974.

- 1 2 Pfeiffer & Worrall 1998, p. 102.

- ↑ Exotic Locations (NTSC, Widescreen, Closed-captioned) (DVD). The Man with the Golden Gun Ultimate Edition, Disc 2: MGM/UA Home Video. 2000.

- ↑ Blame it all on Honey and her white bikini

- ↑ Smith 2002, p. 135.

- ↑ Oswald Morris. The Man with the Golden Gun audio commentary. The Man with the Golden Gun Ultimate Edition, Disk 1: MGM Home Entertainment.

- 1 2 Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 119.

- ↑ John Barry. The Man with the Golden Gun audio commentary. The Man with the Golden Gun Ultimate Edition, Disk 1: MGM Home Entertainment.

- ↑ "The Astro-Spiral Jump". McHenry Software. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ↑ "Top Gear – Season 11, Episode 2 – 29 June 2008". Final Gear.com. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- ↑ Peter Murton. The Man with the Golden Gun audio commentary. The Man with the Golden Gun Ultimate Edition, Disk 1: MGM Home Entertainment.

- ↑ Derek Meddings. The Man with the Golden Gun audio commentary. The Man with the Golden Gun Ultimate Edition, Disk 1: MGM Home Entertainment.

- 1 2 3 Pfeiffer & Worrall 1998, p. 103.

- ↑ Cork & Stutz 2007, p. 235.

- ↑ Borland, Sophie (21 January 2008). "Lightsabre wins the battle of movie weapons". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ↑ Adams, Stephen (10 October 2008). "James Bond golden gun stolen from Elstree Studios". The Daily Telegraph (London). Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- ↑ Bramwell & Kingsland 2006, p. 368.

- ↑ Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 92.

- ↑ Greene 1974, p. 40.

- ↑ Cork & Stutz 2007, p. 287.

- ↑ Barry, John (interviewee) (2006). James Bond's Greatest Hits (Television). UK: North One Television.

- ↑ Music – The Man With The Golden Gun. Mi6-HQ.com. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ↑ Hickey, William (20 December 1974). "Shaking on it – one man to another". Daily Express.

- ↑ Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 116.

- ↑ "The Man with the Golden Gun". The Numbers. Nash Information Services, LLC. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ "Box Office History for James Bond Movies". The Numbers. Nash Information Services, LLC. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ Ambridge, Geoffrey (July 2007). "Lone Star's 'Top Ten' Diecast guns". Collectors' Gazette (280): 12, 13.

- 1 2 Malcolm, Derek (19 December 1974). "Rebel without a pause". The Guardian.

- 1 2 Milne, Tom (22 December 1974). "From Badlands to Bond". The Observer.

- 1 2 3 Robinson, David (20 December 1974). "A trip back to the forest of Dean". The Times.

- ↑ Sayre, Nora (19 December 1974). "Movie Review – The Man with the Golden Gun – Film: James Bond and Energy Crisis". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- 1 2 Thirkwell, Arthur (18 December 1974). "It's Bond, shaky – but still stirring". Daily Mirror.

- ↑ Crist, Judith (23 December 1974). "Movies – All in the Family". New York.

- 1 2 Cocks, Jay (13 January 1975). "Cinema: Water Pistols". Time. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- ↑ "The Man with the Golden Gun". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 24 September 2007.

- ↑ Freer, Ian (13 October 2008). "The Man with the Golden Gun". Empire. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ↑ "James Bond's Top 20". IGN. 17 November 2006. Retrieved 21 December 2007.

- ↑ Svetkey, Benjamin; Rich, Joshua (14 November 2008). "James Bond: Ranking 21 films". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- ↑ Norman Wilner. "Rating the Spy Game". MSN. Archived from the original on 19 January 2008. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- ↑ Berardinelli, James (1996). "The Man with the Golden Gun". ReelViews. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- 1 2 Peary 1986, p. 264.

- ↑ Nashawaty, Chris (12 December 2008). "Moore ... and Sometimes Less". Entertainment Weekly (1025). Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- ↑ Rich, Joshua (10 November 2006). "6. Mary Goodnight (Britt Ekland)". 10 worst Bond girls. Retrieved 11 August 2011.

- ↑ Plant, Brendan (1 April 2008). "Top 10 Bond villains". The Times. Retrieved 11 August 2011.

- ↑ Copping, Nicola (1 April 2008). "Top 10 most fashionable Bond girls". The Times. Retrieved 11 August 2011.

- ↑ "The Top Bond Babes". Maxim. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

Sources

- Barnes, Alan; Hearn, Marcus (2001). Kiss Kiss Bang! Bang!: the Unofficial James Bond Film Companion. Batsford Books. ISBN 978-0-7134-8182-2.

- Benson, Raymond (1988). The James Bond Bedside Companion. London: Boxtree Ltd. ISBN 1-85283-234-7.

- Black, Jeremy (2004). Britain Since the Seventies: Politics and Society in the Consumer Age. Guilford: Biddles Ltd. ISBN 978-1-86189-201-0.

- Black, Jeremy (2005). The Politics of James Bond: from Fleming's Novel to the Big Screen. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-6240-9.

- Bramwell, Tony; Kingsland, Rosemary (2006). Magical Mystery Tours: My Life with the Beatles (reprint ed.). Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-0-312-33044-6.

- Broccoli, Albert R (1998). When the Snow Melts. London: Boxtree Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7522-1162-6.

- Cork, John; Stutz, Collin (2007). James Bond Encyclopedia. London: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-1-4053-3427-3.

- Fu, Poshek; Desser, David (2000). The Cinema of Hong Kong. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77235-8.

- Greene, Bob (1974). Billion dollar baby. Athéneum. ISBN 978-0-689-10616-3.

- Mankiewicz, Tom; Crane, Robert (2012). My Life as a Mankiewicz. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-3605-9.

- Macintyre, Ben (2008). For Yours Eyes Only. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7475-9527-4.

- Peary, Danny (1986). Guide for the Film Fanatic. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-61081-4.

- Pfeiffer, Lee; Worrall, Dave (1998). The Essential Bond. London: Boxtree Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7522-2477-0.

- Smith, Jim (2002). Bond Films. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-7535-0709-4.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Man with the Golden Gun (film) |

- The Man with the Golden Gun at BFI Screenonline

- The Man with the Golden Gun at the Internet Movie Database

- The Man with the Golden Gun at AllMovie

- The Man with the Golden Gun at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Man with the Golden Gun at Box Office Mojo

- The Man with the Golden Gun at the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer site

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||