The Helga Pictures

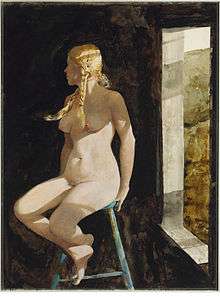

The Helga Pictures are a series of more than 240 paintings and drawings of German model Helga Testorf (born c. 1933[1][2] or c. 1939[3][4]) created by Andrew Wyeth (1917–2009) between 1971 and 1985.

Creation

Helga Testorf was a neighbor of Wyeth's in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, and over the course of fifteen years posed for Wyeth indoors and out of doors, nude and clothed, in attitudes that reminded writers of figures painted by Botticelli and Édouard Manet.[2][5] To John Updike, her body "is what Winslow Homer's maidens would have looked like beneath their calico."[6]

Born in Germany, Helga entered a Prussian Protestant convent chosen by her father in 1955. After becoming seriously ill she left the convent and lived in Mannheim, where she studied to be a nurse and a masseuse.[3] In 1957, she met John Testorf, a German-born, naturalized American citizen, whom she married in 1958.[3] By 1961 they were living in Philadelphia, where she worked in a tannery, but they soon moved to Chadds Ford.[3] There she raised a family that would grow to include four children,[7] and acted as caretaker to farmer Karl Kuerner, an elderly neighbor who was a friend and model for Wyeth.[4]

Wyeth asked Testorf to model for him in 1971, and from then until 1985 he made 45 paintings and 200 drawings of her, many of which depicted her nude. The sessions were a secret even to their spouses.[8] The paintings were stored at the home of his student, neighbor and good friend, Frolic Weymouth.

Aftermath

Explaining the series, Wyeth said, "The difference between me and a lot of painters is that I have to have a personal contact with my models. ... I have to become enamored. Smitten. That's what happened when I saw Helga."[9] He described his attraction to "all her German qualities, her strong, determined stride, that Loden coat, the braided blond hair".[10] Art historian John Wilmerding wrote, "Such close attention by a painter to one model over so long a period of time is a remarkable, if not singular, circumstance in the history of American art".[1] For art critic James Gardner, Testorf "has the curious distinction of being the last person to be made famous by a painting".[9]

When the existence of the pictures was made public images of Testorf graced the covers of both Time and Newsweek magazines.[7][11] Testorf, although flattered by the paintings, was upset by the publicity and controversy they provoked.[7] Although Wyeth denied that there had been a physical relationship with Testorf, the secrecy surrounding the sessions and public speculation of an affair created a strain in the Wyeths' marriage.[12]

Well after the paintings were finished, Testorf remained close to Wyeth and helped care for him in his old age.[4] In a 2007 interview, when Wyeth was asked if Helga was going to be present at his 90th birthday party, he said, "Yeah, certainly. Oh, absolutely," and went on to say, "She's part of the family now. I know it shocks everyone. That's what I love about it. It really shocks 'em."[13]

Exhibitions and ownership

In 1986, Philadelphia publisher and millionaire Leonard E.B. Andrews (1925–2009) purchased almost the entire collection, preserving it intact. Wyeth had already given a few Helga paintings to friends, including the famous Lovers, which had been given as a gift to Wyeth's wife.[14] [15] The works were exhibited at the National Gallery of Art in 1987 and in a nationwide tour.[16] There was extensive criticism of both the 1987 exhibition and the subsequent tour.[15] The show was "lambasted" as an “absurd error” by John Russell and an “essentially tasteless endeavor” by Jack Flam, coming to be viewed by some people as "a traumatic event for the museum."[15] The curator, Neil Harris, labeled the show “the most polarizing National Gallery exhibition of the late 1980s,” himself admitting concern over "the voyeuristic aura of the Helga exhibition."[17]

The tour was criticized after the fact because, after it ended, the pictures' owner sold his entire cache to a Japanese company, a transaction characterized by Christopher Benfey as "crass."[15]

List of works

- This list is incomplete; you can help by expanding it.

- Letting Her Hair Down (1972)

- Sheepskin (1973)

- Braids (1977)

- Farm Road (1979)

- Day Dream (1980)

Drybrush and/or watercolor on paper:

- Black Velvet (1972)

- The Prussian (1973)

- In the Orchard (several versions, 1973–85)

- Seated by a Tree (1973, other versions from 1973 and 1982)

- Crown of Flowers (1974)

- Loden Coat (1975)

- Easter Sunday (1975; a non-Helga watercolor also bears this title)

- Barracoon (1976; a non-Helga tempera also bears this title)

- On Her Knees (1977)

- Drawn Shade (1977)

- Overflow (1978)

- Walking In Her Cape Coat (1979)

- Night Shadow (1979)

- Pageboy (1980)

- Knapsack (two versions, both 1980)

- Lovers (1981)

- From the Back (two versions, both 1981)

- In the Doorway (three versions, all 1981)

- Cape Coat (1982)

- Campfire (two versions, both 1982)

- Sun Shield (1982)

- Flotation Device (1984)

- Autumn (1984)

- Refuge (1985)

- Red Sweater (1987)

- Helga's Back (1991)

- Barefoot (1992)

- Uphill (1999)

- Gone (2002)

Notes

- 1 2 Wilmerding, 11

- 1 2 Updike, 176

- 1 2 3 4 Meryman, 335

- 1 2 3 "Andrew Wyeth's Helga Pictures: An Intimate Study", Resource Library Magazine, Jocelyn Art Museum.

- ↑ Wilmerding, 13-14

- ↑ Updike, 185-186

- 1 2 3 "Andrew Wyeth's Stunning Secret", Time, August 18, 1986. Retrieved on March 27, 2010.

- ↑ Meryman, 335-375

- 1 2 Gardner, James. "A Villain in Pigtails". The New York Sun, November 2, 2006. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ↑ "The Rejection of the Regionalists: Wyeth, Wood, and the New Americans". The Harvard Advocate

- ↑ Updike, 175

- ↑ "Still Sovereign of His Own Art World", New York Times, 18 February 1997

- ↑ Lieberman, Paul (July 18, 2007), Nudity, explosives and art, Los Angeles Times, retrieved August 21, 2011

- ↑ Monday, Aug. 18, 1986 (August 18, 1986). ""Andrew Wyeth's Stunning Secret," ''Time'', Monday, Aug. 18, 1986". Time.com. Retrieved January 17, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 "Wyeth and the Pursuit of Strangeness" by Christopher Benfey, The New York Review of Books, 19 June 2014

- ↑ Andrew Wyeth's Helga Pictures: An Intimate Study, Traditional Fine Arts Organization, 2002

- ↑ Harris, Neil. Capital Culture: J. Carter Brown, the National Gallery of Art, and the Reinvention of the Museum Experience; University of Chicago Press; 2013; pp. 438–442; ISBN 9780226067704

References

- Meryman, Richard: Andrew Wyeth: A Secret Life, HarperCollins 1996. ISBN 0-06-017113-8.

- Updike, John. Just Looking: Essays on Art. Alfred A. Knopf, 1989. ISBN 0-394-57904-6

- Wilmerding, John. Andrew Wyeth: The Helga Pictures. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1987. ISBN 0-8109-1788-2