The Clancy Brothers

| The Clancy Brothers | |

|---|---|

|

The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem in the 1960s (left-to-right: Tommy Makem, Paddy Clancy, Tom Clancy, and Liam Clancy) | |

| Background information | |

| Also known as | The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem, The Clancy Brothers and Louis Killen, The Clancy Brothers and Robbie O'Connell, The Clancy Brothers and Eddie Dillon |

| Origin | County Tipperary & County Armagh, Ireland |

| Genres | Traditional Irish, Folk, Celtic |

| Years active | 1956–1998 |

| Labels | Tradition Records, Columbia Records, Audio Fidelity Records, Vanguard Records, Blackbird Records, Shanachie Records, Helvic Records |

| Associated acts | Makem and Clancy, The Clancys and Eddie Dillon, The Fureys, Clancy, O'Connell & Clancy, Cherish the Ladies, The High Kings, Danú, The Makem Brothers, Barley Bree, The Clancy Legacy |

| Past members |

Liam Clancy Paddy Clancy Tom Clancy Tommy Makem Bobby Clancy Louis Killen Robbie O'Connell Finbarr Clancy Eddie Dillon |

The Clancy Brothers were an influential Irish folk group, which initially developed as a part of the American folk music revival. Most popular in the 1960s, they were famed for their trademark Aran Jumpers and are widely credited with popularising Irish traditional music in the United States and revitalising it in Ireland, paving the way for an Irish folk boom with groups like The Dubliners and The Wolfe Tones.[1][2][3][4][5]

The Clancy Brothers, Patrick "Paddy" Clancy, Tom Clancy, and Liam Clancy, are best known for their work with Tommy Makem, recording almost two dozen albums together as The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem. Makem left in 1969, the first of many changes in the group's membership. The most notable subsequent member to join was the fourth Clancy brother, Bobby Clancy. The group continued in various formations until Paddy Clancy's death in 1998.

The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem significantly influenced the young Bob Dylan and other emerging artists, including Christy Moore and Paul Brady.[6][7] The group was famous for its often lively arrangements of old Irish ballads, rebel and drinking songs, sea shanties, and other traditional music.[5][8]

History

Original group with Tommy Makem

Early years

The oldest member of the group, Paddy Clancy, was born on 7 March 1922 in Carrick-on-Suir, County Tipperary, Ireland. Tom followed on 29 October 1924, Bobby on 14 May 1927, and youngest brother Liam Clancy on 2 September 1935. Tommy Makem was born 4 November 1932 in Keady, County Armagh, Northern Ireland.

After serving in World War II in the Royal Air Force, Paddy and Tom emigrated from England to Toronto in 1947 on the S.S. Marine Flasher, accompanying 400 war brides. The only men on board were Paddy, Tom, their friend Pa Casey and the ship's sailors.[9] Once in Toronto, Paddy and Tom worked various odd jobs before coming to the United States two years later, through the sponsorship of two aunts. Residing for a time in Cleveland, Ohio, the two brothers began to dabble in acting. They decided to move to Hollywood, but their car broke down soon after the trip began. They relocated to the New York City area instead.[10]

Arriving in Greenwich Village in Manhattan in 1951, Tom and Paddy established themselves as successful Broadway and Off-Broadway actors. They also made several television appearances. The two brothers created their own production company, Trio Productions, which lead to the start of their professional singing careers.[11] To help raise money for the company, Paddy and Tom organised late-night concerts of folk songs called the 'Swapping Song Fair' (later renamed the 'Midnight Special'[12]) every Saturday night at the Cherry Lane Theatre, which they were renting at the time to produce Irish plays.[13] Here they would sing some of the old Irish songs that they knew from their childhood. Some well-known folk singers, including Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, and Jean Ritchie, also participated in these concerts.[13] At this time, younger brother Bobby Clancy briefly emigrated to New York City, joining his brothers in Greenwich Village. This was the little-known, first 'unofficial' line-up of singing Clancy brothers.

In 1955, Bobby returned home to Carrick-on-Suir to take over father Robert J. Clancy's insurance business, freeing youngest brother Liam Clancy to emigrate to New York City to pursue his dream of acting.[14] Liam arrived in New York in January 1956.

A month earlier, Tommy Makem emigrated to the United States from his hometown of Keady. Tommy had met Liam Clancy shortly before they both emigrated. Diane Hamilton, a friend of Paddy Clancy in New York, followed in the footsteps of her mentor, Jean Ritchie, and came to Ireland in search of rare Irish songs. Her first stop was at the Clancy household, where she recorded several members of the family, including the Clancys' mother, sisters Peg and Joan, and nineteen-year-old Liam Clancy. Hamilton asked Liam and recently returned Bobby Clancy to join her on a trek through Ireland to locate and record source singers.

One of those source singers was Sarah Makem who had been recorded by Jean Ritchie in 1952 on a similar search for authentic Irish folk songs. Her son Tommy Makem, then twenty-two, and the young Liam Clancy instantly became friends. Said Liam, "Our interests were so similar: girls, theater and music. He had told me he was going to America to try his luck at acting. We agreed to keep in touch." Tommy was recorded for the first time by Hamilton in that autumn of 1955. Among the songs he sang was "The Cobbler," which he continued to perform throughout his career.

Group's formation and Tradition Records

In March 1956, Tommy Makem was unemployed. He had recently moved to Dover, New Hampshire, where many of his family members had emigrated to work in the local cotton mills. He had found a job there making printing presses but had an accident when a two-ton steel press that he was guiding with his hand broke from its chain. The falling press tore the tendons from the bone in three of the fingers of his left hand.[15] His hand in a sling, and knowing the Clancy brothers in New York, he decided that he would like to make a record with them.[12] He told this to Paddy Clancy, who with the sponsorship of Diane Hamilton and the assistance of his brother Liam founded a record company, Tradition Records, in 1956.[16] Paddy agreed and together he, Tom, Liam, and Tommy Makem recorded an album of Irish rebel songs, The Rising of the Moon, one of the new label's first releases.[12] Paddy's harmonica provided the only musical accompaniment for this debut album.

Little thought was given to continuing as a singing group. They all were busy establishing theatrical careers for themselves, in addition to their work at Tradition Records.[12] But the album was a local success and requests were often demanded for the brothers and Tommy Makem to sing some of their songs at parties and informal pub settings. Slowly, the singing gigs began to outweigh the acting gigs and by 1959, serious thought was given to a new album. Liam had developed some guitar skills, Tommy's hand had healed enough he was again able to play tin whistle and bagpipes, and the times spent singing together had improved their style. No longer were they the rough, mostly unaccompanied group of actors singing for an album to jumpstart a record label; they were becoming a professional singing group.

The release of their second album, this one of Irish drinking songs called Come Fill Your Glass with Us, solidified their new careers as singers. The album was a success,[17] and they made many appearances on the pub circuit in New York, Chicago, and Boston. It was at their first official gig after Come Fill Your Glass With Us that the group finally found a name for themselves. The nightclub owner asked for a name to put on the marquee, but they had not decided on one yet. Unable to agree on a name (which included suggestions like The Beggermen, The Tinkers and even The Chieftains) the owner decided for them, simply billing them as "The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem".[12] The name stuck. They decided to try singing full-time for six months. If their singing was successful, they would continue with it; if not, then they would return to acting.[12] The Clancy brothers and Tommy Makem proved successful as a singing group and in early 1961, they attracted the attention of scouts from The Ed Sullivan Show.

Famous sweaters and initial success

The Clancy Brothers' mother read news of the terrible ice and snow storms in New York City and sent Aran sweaters for her sons and Tommy Makem to keep them warm. They wore the sweaters for the first time at the Blue Angel nightclub in Manhattan, simply as part of their regular winter clothes. When the group's manager Marty Erlichman, who had been searching for a special "look" for the group, saw the sweaters, he exclaimed, "That's it! That's it! That's what you're going to wear." Ehrlichman requested that the group wear the sweaters on their upcoming television appearance on the The Ed Sullivan Show. After they did, the sales of Aran sweaters rose by 700% according to Liam Clancy, and they soon became the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem's trademark costume.[9][18][19]

On 12 March 1961, the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem performed for around fifteen minutes in front of a television audience of forty million people for the first time on The Ed Sullivan Show.[9] A previously scheduled artist did not appear that night, and the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem were given the newly available time slot on the show, in addition to the two songs they had initially planned to do. The televised performance and the success of the Clancys' and Makem's nightclub performances attracted the attention of John Hammond of Columbia Records. The group was offered a five-year contract with an advance of $100,000, a huge sum in 1961. For their first album with Columbia, A Spontaneous Performance Recording, they enlisted Pete Seeger, one of the leaders of the American Folk Revival, as backup banjo player. The record included songs that would soon become classics for the group, such as "Brennan on the Moor," "Jug of Punch," "Reilly's Daughter," "Finnegan's Wake," "Haul Away Joe," "Roddy McCorley," "Portlairge," and "The Moonshiner." The album was nominated for a Grammy Award in 1962.[20]

Around the same time that they recorded A Spontaneous Performance, the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem cut their final, eponymous album with Tradition Records. By the end of 1962, they released a second album with Columbia, Hearty and Hellish! A Live Nightclub Performance, and they played an acclaimed concert at Carnegie Hall. Additionally, they were making appearances on major radio and television talk-shows in America.

International stardom

In late 1962 Ciarán MacMathuna, a popular radio personality in Ireland, first heard of the group while visiting America. He collected their first three Columbia albums, A Spontaneous Performance Recording, Hearty and Hellish!, and The Boys Won't Leave the Girls Alone, brought them back home to Ireland, and played them on his radio show. The broadcasts skyrocketed the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem to fame in Ireland, where they had been unknown. In Ireland, songs like "Roddy McCorley," "Kevin Barry" and "Brennan on the Moor" were slow, moving songs, but the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem had transformed those songs (some purists in Ireland argued, "commercialized") and made them lively. The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem were brought over for a sold-out tour of Ireland in late 1963. Popularity in England and other parts of Europe soon followed, as well as in Australia and Canada.

By 1963, appearing on major talk-shows in America, Canada, England, Australia and Ireland, as well as their own TV specials, the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem were "the most famous four Irishmen in the world," according to Ireland's Late Late Show host, Gay Byrne, in a retrospective interview in 1984.[21] Billboard Magazine reported that the group was outselling Elvis Presley in Ireland, adding that this was "a most unusual situation" for folk singers.[22] In 1964, almost one third of all the albums sold in Ireland were Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem records.[23]

The 1960s continued to be a successful decade with the release of approximately two albums per year, all of which sold millions of copies. In 1963 they made a prestigious televised appearance in front of President John F. Kennedy. Makem rewrote an old song, "We Want No Irish Here," expressly for the occasion.[15]

In late 1963, the group released its most successful album, In Person at Carnegie Hall, which spent twelve weeks on the Billboard chart for the top 150 albums of any genre in release in the United States. It broke the top 50 albums in December, an unprecedented occurrence for an Irish folk music recording.[24] The Clancy Brothers' follow-up album, The First Hurrah!, also charted in the top 100 albums in the US in 1964.[25][26] A single taken from that album, "The Leaving of Liverpool," was a top ten hit in Ireland.[27][28] Another album, Isn't It Grand Boys, appeared on the British charts in 1965.[29] In the mid-1960s, the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem continued to release live albums: Recorded Live in Ireland, Freedom's Sons, and In Concert. In 1966, they also participated in the making of The Irish Uprising, an educational recording with music, speeches, and a historical booklet, celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of the Easter Uprising.

The group's popularity in the 1960s was the result of several factors. There was already an American folk revival beginning in the United States, and men such as Ewan MacColl popularising old songs on the other side of the Atlantic. But it was the Clancys' boisterous performances that set them apart, taking placid classics and giving them a boost of energy and spirit (not that they took this approach with all their songs; they would still sing the true mournful ballads with due reverence). However, by the late 1960s, the ballad and folk boom was waning. In an attempt keep the Clancys profitable, Teo Macero, who usually worked on jazz albums, began producing their records for Columbia. Macero introduced new instrumentation to the Clancys' music, including bringing in Louis Killen to play back-up concertina, particularly on their 1968 album of sea songs, Sing of the Sea. Their last three albums for Columbia Records in 1969 and 1970 represent a significant shift in style for the group, with a multitude of string instruments and synthesizers added to the simpler traditional Clancy mix of guitar, banjo, tin whistle, and harmonica.

In 1969, the group recorded a song for a two-minute-long TV ad for Gulf Oil: "Bringin' Home the Oil". They adapted a traditional Scottish tune they had recorded, "The Gallant Forty Twa," with new words about large-capacity supertankers. The song and commercial featured the then-largest supertanker in the world, the Universe Ireland, which operated with sister ships Universe Kuwait, Universe Japan and Universe Portugal, all mentioned in the song and which operated from the seaport at Bantry Bay.

Later line-ups

Changes in the group

A major change occurred in 1969, when Tommy Makem amicably left the group after cutting one more album with the Clancys, The Bold Fenian Men. After a year's notice, Makem departed in April to pursue a solo career, armed with such recent compositions as "Four Green Fields," which had debuted on the 1968 album, Home Boys Home. He later explained his grounds for leaving: "The reason I wanted to leave was that I found myself in a groove—a very comfortable groove where I could make a very good living. But there was no challenge there for me anymore, and I needed that challenge to stimulate myself."[30]

Another Clancy brother, Bobby, filled Tommy Makem's vacancy as the fourth lead vocalist. Two of the Furey Brothers, Finbar and Eddie, also joined at this time as instrumentalists and back-up singers. Paddy asked Finbar Furey if he would play the whistle and five-string banjo with the group. Finbar also added uillean pipes to his performances, creating a new sound for the group on stage, recordings, and TV. The six-piece band recorded two new albums in the summer of 1969: Clancy Brothers Christmas, released later that year, and Flowers in the Valley, released in 1970. The latter was their final album for Columbia Records.

Finbar and Eddie Furey left in 1970, and for a short time just the four brothers, Paddy, Tom, Bobby and Liam, performed together. This line-up recorded only one album together, Welcome to Our House, in 1970 for their new label, Audio Fidelity Records. Later that same year, Liam and Bobby got into an argument that resulted in Bobby quitting the group. Bobby later said about his younger brother: "With Liam it was very hard to be equal. I try to make it as equal as possible and everybody's happy that way. It makes it a better sound."[31]

In 1971, the remaining Clancys recruited English folk singer, Louis Killen, to play the banjo, concertina, and spoons with the group. Together they made two studio albums for Audio Fidelity, Save the Land and Show Me the Way, on which they experimented with modernising their sound, musical style, and material, even including pop songs like Elton John's "Country Comfort." They recorded their final album for Audio Fidelity, the more traditional Live on St. Patrick's Day, at the Bushnell Auditorium in Hartford, Connecticut in 1972. It was released the following year.

By the early 1970s, the Clancys reduced their touring schedule to five months a year. The brothers were moving in different directions, and all of them had young families at home. Paddy had moved back to Ireland in 1968. Tom began acting again, first on stage and then on film and television. He relocated to the Los Angeles area in 1975, where he landed parts in the films, The Killer Elite with James Caan and Robert Duvall and Swashbuckler with Robert Shaw. At the same time, Liam wanted to step out from his older brothers' shadows. According to the 2009 feature documentary, The Yellow Bittern: The Life and Times of Liam Clancy, Paddy and Tom Clancy dominated the group in ways that Liam felt was personally limiting.[32] He moved to Calgary, Alberta, Canada in 1972 and began a solo career when not touring with his brothers. In spite of the brothers' growing distance, the group made one more album with Killen for Vanguard Records, The Clancy Brothers' Greatest Hits, as well as several television appearances on the Irish Rovers Show in Canada and a TV special for Brockton television in 1974 (in which Bobby Clancy made a surprise guest appearance).

A scheduling conflict between a tour of Australia and a television role with Tom Clancy provoked Liam to leave the group in early 1976. Tom allegedly accepted a television role over the tour of Australia, even though he had already signed a contract to do the tour. When confronted over the conflict, Liam later recalled Tom telling him, "Get off my fucking back, little brother." Soon afterwards, their sister Cait Clancy O'Connell was killed in a car crash. After the funeral in Ireland, Liam told his brothers that they would have to find a replacement for him. "I'm not going to work with you anymore—I can't be the 'little brother' anymore," Liam said, according to an interview in the The Yellow Bittern.[32] Louis Killen left as well, and Paddy and Tom decided to take a short hiatus from singing.

The temporary dissolution of the group permitted Paddy Clancy to devote his full attention to the dairy and cattle breeding farm in Tipperary he had bought with his wife in 1963. Tom's acting career flourished in Hollywood, where he regularly appeared in movies, TV films and shows, such as Little House on the Prairie, The Incredible Hulk, Charlie's Angels and Starsky and Hutch. Liam, suffering financial setbacks due to tax problems, filed for bankruptcy and moved to his sister-in-law's house in Calgary. His brother-in-law helped to get him some concert gigs there. Liam was introduced to "The Dutchman" at this time, which became one of his most popular songs. His gigs in Calgary caught the attention of a TV producer, who signed Liam to host twenty-six episodes of his own music and talk show. On the final episode, Tommy Makem appeared as a guest. This led the two of them to be signed together for twenty-six additional episodes. Their program was called The Makem & Clancy Show. The success of the show led them to form the group Makem and Clancy. After several albums and tours, an American television series, and thirteen years together, the duo split up in 1988.

Robbie O'Connell joins

Meanwhile, after taking the rest of 1976 off, Paddy and Tom made plans to bring back the Clancy Brothers. They asked Bobby Clancy to return to the group. Tom was at the height of his new career in Hollywood and Paddy was busy with his farm, so it was ultimately decided to tour on a part-time basis and only in the United States. Their recently deceased sister Cait's son, Robbie O'Connell, was an up-and-coming musician in the US and in Ireland; he was also helping manage, along with Bobby, the inn that Cait had opened up years before. They asked him to take on the role Liam had vacated in the group. He played the guitar and occasionally the mandolin, while Bobby played the banjo, guitar, harmonica, and bodhrán. Paddy continued to play the lead harmonica.

Beginning in 1977, the Clancy Brothers and Robbie O'Connell toured three months a year in March, August, and November. Tom would fly over a few days before each tour and rehearse material, mostly oldies from their 1960s albums but some new ones as well. Robbie was a songwriter, composing several numbers the group sang regularly, such as "Bobby's Britches," "Ferrybank Piper," "There Were Roses," and "You're Not Irish." He also included songs written by others, such as "Dear Boss," "Sister Josephine," "John O'Dreams," and what is possibly his signature song, "Killkelly." Bobby also sang numbers new to the group, including "Love of the North," "Song for Ireland," and "Anne Boleyn." In America, the Clancy Brothers continued where they had left off the previous year, still packing Carnegie Hall. Reviews cited Robbie as a fresh addition to the group with his original compositions.

Over the next several years, Paddy and Tom brought in some new material too. "The Green Fields of France," also known as "Willie McBride," by Eric Bogle had become a hit with a recording by the Clancys' old back-up musicians, the Furey Brothers, in the early 1980s. Soon numerous Irish groups were singing it, including the Clancy Brothers and Makem and Clancy. It became a staple in Tom's repertoire. He also sang "Logger Lover." The group added new lyrics to the old Irish ballad, "She Didn't Dance," and reworked old classics, such as "As I Roved Out," "Beer, Beer, Beer," and "Rebellion 1916 Medley." Some of these songs appeared on the Clancy Brothers' first album in nine years, The Clancy Brothers with Robbie O'Connell Live! (1982).

In the summer of 1983, the group travelled to their hometown in Ireland to film a 20-minute special on sea songs, sung on location on the fishing ships in the area. It was called Songs of the Sea. Directed by Irish filmmaker David Donaghy, it was broadcast on the BBC Northern Ireland. Tom tried on many occasions to put it on videocassette but the plans fell through.

Reunion

In 1984, Makem and Clancy's manager Maurice Cassidy brought the original foursome together again for a documentary to be followed by a concert at Lincoln Center in New York City. Paddy and Tom Clancy took some time out from the Clancy Brothers and Robbie O'Connell and joined forces with Makem and Clancy. Paddy, Tom, Liam, and Tommy Makem were reunited, and production on the documentary commenced after a 90-minute debut on Ireland's Late Late Show on 28 April. The documentary crew followed the group around, travelling to Carrick-on-Suir, Keady, Greenwich Village, a dress rehearsal concert at Tommy Makem's Irish Pavilion on East 57th Street, and finally Lincoln Center for the recorded concert on 20 May 1984.[12] The 3,000 seat Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center had sold out for the show within a week. The rowdy audience provided enthusiastic participation on the album, released as Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem Reunion. A reunion tour of Ireland, England, and the United States followed in late 1984 and the fall of 1985.[33] After the tour, Makem and Clancy and the Clancy Brothers and Robbie O'Connell respectively regrouped.

In the late 1980s and 1990s

In 1988, the Clancy Brothers (Paddy, Tom, and Bobby) with Robbie O'Connell recorded a poorly mixed live album at St. Anselm College in Goffstown, New Hampshire, Tunes 'n' Tales of Ireland. Bobby Clancy called this album "crap," and Paddy referred to it as "not our best effort."[34] Regardless, the album is notable as Tom Clancy's final record.

In May 1990, Tom Clancy was diagnosed with stomach cancer. When he had surgery later in the summer, Liam filled in for him during the Clancy Brothers and Robbie O'Connell's August tour. The surgery proved unsuccessful, and Tom Clancy died at the age of 66 on 7 November 1990. He left behind a wife, a son, and five daughters. His youngest daughter was only two years old at the time.

With the death of Tom Clancy, Liam again stepped in full-time with his brothers. This line-up experienced a more active schedule than the group had during the previous decade, with appearances on Regis and Kathie Lee in 1991, 1993 and 1995, a performance at the 30th Anniversary Bob Dylan concert at Madison Square Garden in 1992, seen by 20,000 live and 200 million people worldwide on television, and the formation of Irish Festival Cruises in 1991, an annual cruise of the Caribbean with live folk music. They also brought their own tour groups to Ireland, which Robbie O'Connell continues to do to this day.

The Bob Dylan concert inspired the recording of the first studio album by the Clancy Brothers in over twenty years, since 1973's Greatest Hits. Released in late 1995, Older But No Wiser introduced all newly recorded songs with the exception of "When the Ship Comes In," which the group performed at the Dylan concert. It was the only recording to feature the line-up of Paddy, Bobby, Liam Clancy, and Robbie O'Connell. Older But No Wiser was the Clancy Brothers' final album.

The Irish Festival Cruises had led to financial disputes between Paddy and Liam. Liam decided to leave the group because of this. Robbie O'Connell, now with the group for nineteen years, was ready for a change as well. The two left the Clancy Brothers together and formed their own duo, simply called Liam Clancy and Robbie O'Connell. Before splitting up, the Clancy brothers and Robbie O'Connell gave a Farewell Tour of Ireland and America in February and March 1996. One performance in Clonmel as part of their Irish tour was televised and later released on video and DVD as The Clancy Brothers and Robbie O'Connell: Farewell to Ireland. On the album Older But No Wiser and the concert video Farewell to Ireland, respectively, two sons of Clancy brothers made their recording debuts. Dónal Clancy, Liam's youngest son, played backup on the studio album, while Bobby's son Finbarr Clancy performed with the group on the filmed Farewell concert. Bobby was not well at this time and Finbarr was brought on, in part, to aid his father for this concert. He had first performed with the group the previous year as a replacement for his father when he had heart surgery. Finbarr did not join them for the American tour.

Later groupings

After the break-up, Paddy and Bobby continued touring as the Clancy Brothers, with Bobby's son Finbarr Clancy becoming an official member of the group. The trio added longtime friend of Bobby's daughter Aoife, Eddie Dillon, to the group for a thirteen city engagement in early 1997. The quartet was known as the Clancy Brothers and Eddie Dillon. Eddie Dillon, a Boston-based musician, is the only American ever to perform with the Clancy Brothers.

Liam Clancy and Robbie O'Connell toured for a while as a duo, but very soon added Liam's son Dónal Clancy to the mix, forming the group, Clancy, O'Connell & Clancy. They released two albums together, an eponymous debut album in 1997 and an album of sea songs in 1998, The Wild and Wasteful Ocean. Robbie O'Connell regards the eponymous Clancy, O'Connell and Clancy album to be his favourite of all his recordings. In 1999, with Liam in Ireland, Robbie in Massachusetts, and Dónal in New York, the trio decided to call it quits as a full-time group. They did, however, occasionally regroup for additional concerts together thereafter.

Deaths of Paddy and Bobby Clancy

The other group members as far back as 1996 had noticed Paddy Clancy's unusual mood swings. In the spring of 1998 the cause was finally detected; Paddy had a brain tumor as well as lung cancer. His wife waited to tell him about the lung cancer, so as not to discourage him when he had a brain operation. The tumor was removed successfully, but the cancer was terminal. When he was told of the cancer, he accepted the diagnosis "with great bravery and courage," according to his wife Mary Clancy. Paddy Clancy died in the morning hours of 11 November 1998, at the age of 76. Two weeks before he died, Bobby called Liam and Paddy together to reconcile their differences—they had been at odds for two years since Liam had left the group. The two brothers did reconcile and the three brothers sang together that night at an informal session at their local pub.[32] Liam, Robbie, and Dónal took time out of their November tour of the US to attend Paddy's funeral. Old partner Tommy Makem also attended. Paddy Clancy was survived by his wife and five children.

After Paddy Clancy's death, Bobby, Finbarr, and Eddie Dillon resumed touring as a trio, The Clancys and Eddie Dillon. This new group recorded a live album in October 1998, Clancy Sing-a-Long Songs, and one in March 2001 during Bobby's last tour. In 1999 Bobby was diagnosed with pulmonary fibrosis, a lung ailment. During his last years Bobby was unable to stand and perform at the same time because he would quickly run out of breath, so the trio began performing sitting down.

In 2000, the Milwaukee Irish Fest had its twentieth anniversary and in celebration, the festival had the entire performing Clancy family sing together on one stage. This one time only line-up included Robbie O'Connell, Dónal, Liam, Bobby, Finbarr, Aoife Clancy, and Eddie Dillon. These festival sets, 18–20 August 2000, were the last times any of the Clancy Brothers appeared onstage together.

By March 2002, Bobby's illness had advanced such that he was unable to sing, necessitating Finbarr and Eddie performing as a duo for their short March 2002 tour. Bobby made one final appearance in February 2002 on an American CBS TV spot promoting Liam's autobiography. On 6 September 2002, Bobby Clancy died at the age of seventy-five. He was survived by three daughters, Finbarr, and his wife Moira.

Liam Clancy's later years

The last surviving Clancy brother, Liam Clancy, continued to tour solo into the twenty-first century. In 2002, Doubleday published his autobiography, Mountain of the Women: Memoirs of an Irish Troubadour. The book covers his early years and the initial formation and early successes of the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem. Clancy appeared in spots promoting the memoir on American and Irish television. Taking some time off from singing, he came back to the stage in full force in 2005 with his tour, "Seventy Years On." He sang as part of the Irish Legends act at the Gaiety Theater in Dublin in August 2005 with Ronnie Drew and Paddy Reilly of The Dubliners.

In March 2006, fifty years after the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem recorded their debut album, Conor Murray wrote the first full-length biography on the group. The book, titled The Clancy Brothers with Tommy Makem & Robbie O'Connell: The Men Behind the Sweaters, chronicles the Clancy Brothers from the birth of Paddy Clancy in 1922 to early 2006. In the same year, a two-hour documentary on Liam Clancy was aired on Irish television, The Legend of Liam Clancy, as well as a new concert special with Tommy Makem and his sons, the five-piece Irish folk group, The Makem and Spain Brothers.

From 2005 to 2009, Clancy was joined onstage and in the studio by Kevin Evans of Evans and Doherty, with whom he had worked occasionally in the 1990s. His last album, The Wheels of Life, was released in October 2008 and featured other prominent musicians, such as Donovan, Mary Black, Gemma Hayes, and Tom Paxton.

Tommy Makem died on 1 August 2007, at the age of 74, after an extended fight with cancer.[35] Two years later Liam Clancy died of pulmonary fibrosis, the same ailment that had taken his brother Bobby. He died on 4 December 2009 at the age of 74 in a hospital in Cork, Ireland.[36][37] He was survived by his wife and seven children.

Legacy and influence

American folk revival

The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem were significant figures in the American folk revival of the early 1960s and played important roles in promoting and influencing the early development of the folk boom. In December 1964, Billboard Magazine listed the group as the eleventh best-selling folk musicians in the United States based on sales figures for that year. The Clancys' friends, Peter, Paul and Mary, Bob Dylan, and Pete Seeger, also appeared on the list in first, seventh, and ninth positions, respectively.[38]

The small folk record company, Tradition Records, that Paddy Clancy ran with the help of his brothers, recorded several significant figures of the folk revival and gave some important musical figures their first start in the recording industry. Tradition produced Odetta's first solo LP, Odetta Sings Ballads and Blues. Bob Dylan later cited this album as his inspiration to become a folk singer.[39] The success of that record helped to further finance the nascent company and led to an additional LP with Odetta on the Tradition label.[40] After the success of her Tradition records, Vanguard records signed her to a prestigious recording contract that led to many more albums.

The Clancys recorded numerous 1960s folk singers, including Jean Ritchie, Ed McCurdy, Ewan MacColl, Paul Clayton, and John Jacob Niles. Carolyn Hester's eponymous album with Tradition led to her first public recognition and her signing with Columbia Records.[41] The Clancys also released the only album on which folk song collector Alan Lomax sang.

Paddy Clancy and Tommy Makem were among the first singers to ever appear at the Newport Folk Festival in 1959.[42] The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem appeared there subsequently several times during the 1960s. The festival is renowned for introducing to a national audience a number of performers who went on to become major stars, most notably Joan Baez and Bob Dylan.

Influence on Bob Dylan

The Clancy Brothers were contemporaries of Bob Dylan, and they became friends as they played the clubs of Greenwich Village in New York in the early 1960s. Howard Sounes in his biography of Dylan describes how Dylan listened to the Clancys singing Irish rebel songs like "Roddy McCorley" which he found fascinating, not only terms of their melodies but also their themes, structures and storytelling techniques. Although the songs were about Irish rebels, they reminded Dylan of American folk heroes. He wanted to write songs on similar themes and with equal depth.[43]

Dylan stopped Liam Clancy and Tommy Makem in the street one day in early 1962 and insisted on singing a new song he had written to the tune of "Brennan On The Moor," a song from the eponymous Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem album on Tradition Records. It was called "Rambling, Gambling Willie" and was Dylan's attempt to replicate Irish folk heroes in an American context. Dylan continued to use the melodies of songs from the Clancys' repertoire for his own lyrics several more times, including "The Leaving of Liverpool" for "Farewell To You My Own True Love," "The Parting Glass" for "Restless Farewell," and "The Patriot Game" for "With God on Our Side."

In an interview with U2's Bono from 1984, Dylan recalled: "Irish music has always been a great part of my life because I used to hang out with the Clancy Brothers. They influenced me tremendously." Later in the interview he added, "[O]ne of the things I recall from that time is how great they all were—I mean there is no question, but that they were great. But Liam Clancy was always my favorite singer, as a ballad singer. I just never heard anyone as good."[44] Dylan reiterated this view on camera for the documentary, The Story of the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem.[12]

Dylan never forgot his debt to the Clancys, which is why he invited them to perform at his 30th anniversary concert at Madison Square Garden. It was Dylan's wish that the party after the concert be held at Tommy Makem's Irish Pavilion, a Manhattan pub owned by Makem. At the exclusive party, attended by George Harrison and Eric Clapton among others, Liam Clancy tentatively asked Dylan if he would mind if the Clancys recorded an album of his songs, arranged in a traditional Irish style. Far from minding, Dylan was flattered by the idea: "Man, would you do that? Would you?" He added, "Liam, you don't realize, do you, man? You're my fucking hero."[45] Although the group never made an entire album of Dylan's music, two of his songs, "When the Ship Comes In" and "Rambin' Gamblin' Willie", appeared on the final Clancy Brothers album, Older But No Wiser, three years later. The 1997 eponymous Clancy, O'Connell, and Clancy album also contained a Dylan number, "Restless Farewell".

Irish folk revival

In assessing the impact of the Clancy Brothers, Irish-American author Frank McCourt wrote in 1999: "They were the first. Before them there were dance bands and show bands and céilidhe bands...but not since John McCormack had Irish singers captured international attention like the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem. They opened the gates to the likes of the Dubliners and the Wolfe Tones and every Irish group thereafter."[3]

Eddie Furey of The Fureys once recalled: "It all starts with the Clancys. They gave us our first break, paved the road for everyone else."[4] Ronnie Drew of the Dubliners explained about the Clancys effect on the Irish folk scene, "They did open it up."[2]

In the documentary, Bringing It All Back Home: The Influence of Irish Music in America, Christy Moore and Paul Brady cited the Clancy Brothers as sparking their initial interest in Irish folk music. In the same program, Bono proclaimed that he "loved the Clancy Brothers" and asserted that Liam Clancy was "one of the great ballad singers."[7]

Continuing legacy

The musical tradition of The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem is carried on by Makem and Spain and by the group, The Clancy Legacy, which consists of Robbie O'Connell, Aoife Clancy (daughter of Bobby Clancy) and Dónal Clancy (son of Liam Clancy). Dónal Clancy released his first solo singing folk album in 2013.

Bobby's son, Finbarr Clancy is a member of the popular Irish folk band, The High Kings. Aoife Clancy was a member of Cherish the Ladies. She is currently performing as a solo singer, while accompanying herself on guitar. She appeared in 2003 on the WoodSongs Old-Time Radio Hour.[46] In addition to performing with guitarist Ted Davis from Boston, on the show she talked about her work with Cherish the Ladies. Another of Bobby Clancy's daughters, Roisin, sometimes performs with her husband, Welsh singer Ryland Teifi.

In the brothers' hometown of Carrick-on-Suir, the Clancy Brothers Festival has taken place every spring since 2008 to commemorate the group's achievements and legacy.

In 2010, a new theatre production about the Clancy Brothers entitled, "'Fine Girl Ye Are' – The Legendary Story of The Clancy Brothers & Tommy Makem," commenced a theatrical tour of Ireland. Produced and narrated by RTÉ Producer, Cathal McCabe, the show featured the Irish ballad group, The Kilkennys.

The 2013 film Inside Llewyn Davis, directed by the Coen Brothers, includes a performance of the Irish song, "The Auld Triangle," by four unnamed folk singers in Aran sweaters intended to be Clancy Brother-like figures. Additional characters in the film were modelled after other real life singers from the Greenwich Village folk scene in 1961, including friends of the Clancy Brothers like Tom Paxton, Bob Dylan, and Jean Ritchie.[47][48][49]

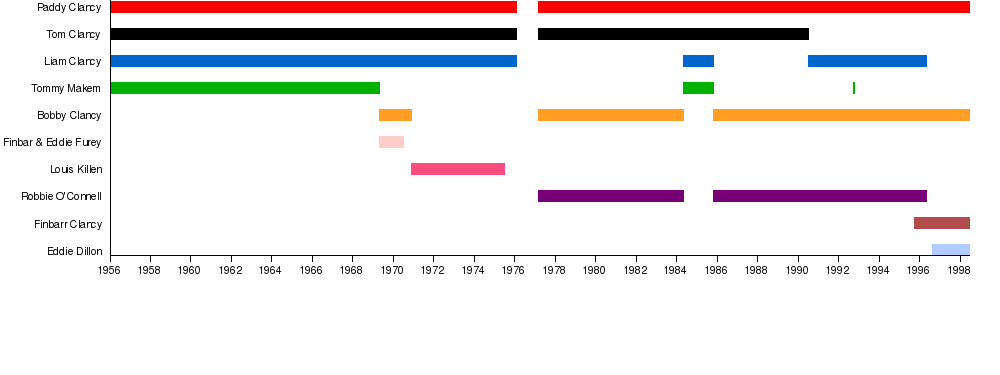

Timeline of group membership

Partial discography

With Tommy Makem

Tradition Records

- The Lark in the Morning (1955) – Tradition LP/Rykodisc CD (with Liam Clancy and Tommy Makem only of the group)

- The Rising of the Moon (or Irish Songs of Rebellion) (1956, 1959 second version)

- Come Fill Your Glass with Us (or Irish Songs of Drinking and Blackguarding) (1959)

- The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem (eponymous) (1961)

Columbia Records

- A Spontaneous Performance Recording (1961)

- Hearty and Hellish! A Live Nightclub Performance (1962)

- The Boys Won't Leave the Girls Alone (1962) – Two stereo issues with alternate mixes issued on out of print Shanachie CDs.

- In Person at Carnegie Hall (1963) – US #50;[24] on Columbia CD

- The First Hurrah! (1964) – US No. 91[25][26]

- Recorded Live in Ireland (1965)

- Isn't It Grand Boys (1966) – UK No. 22[29]

- Freedom's Sons (1966)

- The Irish Uprising (1966)

- In Concert (1967) – on Columbia CD

- Home, Boys, Home (1968)

- Sing of the Sea (1968)

- The Bold Fenian Men (1969)

- Reunion (1984) – released on Blackbird LP/Shanachie CD

- Luck of the Irish (1992) – Columbia/Sony compilation (Contains a new song, Wars of Germany, and three new performances of previously released songs: Home Boys Home, The Old Orange Flute and They're Moving Father's Grave To Build A Sewer.)

- The 30th Anniversary Concert Celebration (1992) – Featuring Bob Dylan & various guests.

- Irish Drinking Songs (1993) – Contains unreleased material from the Carnegie Hall album.

- Ain't It Grand Boys: A Collection of Unissued Gems (1995) – Unreleased material from the 1960s era.[50]

- Carnegie Hall 1962 (2009)

The Clancy Brothers (Liam, Tom, Pat, Bobby)

With Finbar & Eddie Furey

- Christmas – Columbia LP/CD (1969)

- Flowers in the Valley – Columbia LP (1970)

Audio Fidelity Records

- Welcome to Our House (1970)

Lou Killen, Paddy, Liam, Tom Clancy

Audio Fidelity Records

- Show Me The Way (1972)

- Save the Land! (1972)

- Live on St. Patrick's Day (1973)

Vanguard Records

- Clancy Brothers Greatest Hits (1973) – Vanguard LP/CD

*This was reissued as 'Best of the Vanguard Years' with bonus material from the 1982 Live! album with Bobby Clancy and Robbie O'Connell.

Liam Clancy and Tommy Makem

Blackbird and Shanachie Records

- Tommy Makem and Liam Clancy (1976)

- The Makem & Clancy Concert (1977)

- Two for the Early Dew (1978)

- The Makem and Clancy Collection (1980) – contains previously released material and singles

- Live at the National Concert Hall (1983)

- We've Come A Long Way (1986)

Bob Dylan

- The 30th Anniversary Concert Celebration (Pat, Liam & Bobby Clancy sing "When The Ship Comes In" with Tommy Makem and Robbie O'Connell)

The Clancy Brothers (Tom, Pat, Bobby) and Robbie O'Connell

- Live – Vanguard (1982)

- "Tunes and Tales of Ireland" – Folk Era Records(1988)

The Clancy Brothers (Liam, Pat, Bobby) and Robbie O'Connell

- Older But No Wiser – Vanguard (1995)

Clancy, O'Connell & Clancy

Helvic Records

- Clancy, O'Connell & Clancy – (1997)

- The Wild And Wasteful Ocean – (1998)

Tommy Makem

- Ancient Pulsing – Poetry With Music

- The Bard of Armagh

- An Evening With Tommy Makem

- Ever The Winds

- Farewell To Nova Scotia

- In The Dark Green Wood – Columbia Records

- In The Dark Green Woods – Polydor Records

- Live at the Irish Pavilion

- Lonesome Waters

- Love Is Lord of All

- Recorded Live – A Roomful of Song

- Rolling Home

- Songbag

- Songs of Tommy Makem

- The Song Tradition

- Tommy Makem Sings Tommy Makem

- Tommy Makem And Friends in Concert

Liam Clancy

- The Mountain of the Women : Memoirs of an Irish Troubadour – audiobook

- The Dutchman

- Irish Troubadour

- Liam Clancy's Favourites

- The Wheels of Life

Bobby Clancy

- So Early in the Morning – (1962) Tradition LP

- Good Times When Bobby Clancy Sings – (1974) Talbot LP

- Irish Folk Festival Live 1974 (Bobby appears on 4 songs) – (1974) Intercord LP/CD

- Make Me A Cup – (1999) ARK CD

- The Quiet Land – (2000) ARK CD

Robbie O'Connell

- Close to the Bone

- Love of the Land

- Never Learned to Dance

- Humorous Songs – Live

- Recollections (compilation of previous four albums)

Clancy, Evans & Doherty

- Shine on Brighter (featuring Liam Clancy) – (1996) Popular CD

Peg and Bobby Clancy

- Songs From Ireland – (1963) – Tradition LP

Video Footage

Acting

- Treasure Island – The Golden Age of TV Drama

Filmed performances

- The Best of 'Hootenanny'

- Pete Seeger's Rainbow Quest: The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem

- Ballad Session: Bobby Clancy

- The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem: Reunion Concert at the Ulster Hall, Belfast

- Liam Clancy – In Close Up, vol. 1 and 2

- Bob Dylan: The 30th Anniversary Concert Celebration (1 song)

- Lifelines: The Clancy Brothers

- The Clancy Brothers & Robbie O'Connell – Farewell to Ireland

- Live from the Bitter End (Liam Clancy)

- Come West along the Road, vol. 2: Irish Traditional Music Treasures from RTÉ TV Archives, 1960s–1980s (Bobby & Peggy Clancy)

Documentary appearances

- The Story of the Clancy Brothers & Tommy Makem

- Bringing It All Back Home

- No Direction Home: Bob Dylan

- Folk Hibernia

- The Legend of Liam Clancy

- The Yellow Bittern: The Life and Times of Liam Clancy

References

- ↑ Hamill, Denis (22 December 2009). "Last Clancy brother Liam is buried, but clan leaves impression on Irish music". Daily News (New York).

- 1 2 Folk Hibernia (television). BBC 4. 2006.

- 1 2 McCourt, Frank; Harty, Patricia (ed.) (2001), "The Paddy Clancy Call", The Greatest Irish Americans of the 20th Century, Oak Tree Press, pp. 110–112, ISBN 1860762069

- 1 2 Hamill, Dennis (7 November 1999). "'Tis a Fine Way to Honor Paddy Clancy". New York Daily News. pp. City Beat (section).

- 1 2 Madigan, Charles M. (20 November 1998). "Irish Folk Singer Patrick Clancy". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ↑ Lewis, John (16 June 2011). "The Clancy Brothers' mum sends them new sweaters". The Guardian (London).

- 1 2 The Clancy Brothers, Tommy Makem, Robbie O'Connell, Bono, Christy Moore, Paul Brady et al. (1990). Bringing It All Back Home: The Influence of Irish Music in America (television). BBC/RTE.

- ↑ "Folk Music: Old and Young Stars at Town Hall". New York Times. 19 September 1960. p. 42.

- 1 2 3 Gay Byrne (28 April 1984). Late Late Show Special: The Clancy Brothers & Tommy Makem (Part 2) (television). Ireland.

- ↑ Roth, Arthur (Jan–Feb 1972). "Oh that Clancy!". The Critic. pp. 63–68.

- ↑ "The Clancy Brothers and Robbie O'Connell: A Final Farewell?". The Boston Irish Reporter (Dorchester, Mass.) 7 (3): 21. 1 March 1996.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Derek Bailey (Director) (2003, originally 1985). The Story of the Clancy Brothers & Tommy Makem (DVD). Shanachie. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - 1 2 Cohen, Ronald D. (2002). Rainbow Quest: The Folk Music Revival and American Society, 1940–1970. University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 105–106. ISBN 1558493484.

- ↑ "Sad Songs Fighting Songs". Boston Globe. 15 June 1980.

- 1 2 Hanvey, Bobby (8 March 2003). "Every picture tells a story in the world of Bobby Hanvey: Tommy sure to Makem listen [Tommy Makem interview]". The Belfast News Letter: 14.

- ↑ Clancy, Liam (2002). The Mountain of the Women: Memoirs of an Irish Troubadour. New York: Doubleday. p. 143. ISBN 0-385-50204-4.

- ↑ Dexter, Kerry (June 2006). "Recordings: Various Artists; The Clancy Brothers & Tommy Makem". Dirty Linen: 62. ISSN 1047-4315.

- ↑ Clancy, Liam (2002). The Mountain of the Women: Memoirs of an Irish Troubadour. New York: Doubleday. pp. 279–280. ISBN 0-385-50204-4.

- ↑ Gay Byrne (28 April 1984). Late Late Show Special: The Clancy Brothers & Tommy Makem (television). Ireland.

- ↑ "Grammy Awards 1962 (Note: The eponymous album nominated is better known by its subtitle, A Spontaneous Performance)". Awards & Shows. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ↑ Gay Byrne (28 April 1984). Late Late Show Special: The Clancy Brothers & Tommy Makem (television). Ireland.

- ↑ Stewart, Ken (7 September 1963). "Eire: Clancys, Makem Topping Presley". Billboard 75 (36): 37.

- ↑ "Folk music great Paddy Clancy dies aged 76". Independent (Ireland). 1998; updated 10 May 2007. Retrieved 18 April 2014. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - 1 2 "Top LP's". Billboard 75 (51): 10. 21 December 1963.

- 1 2 "Top LP's". Billboard 76 (22): 30. 30 May 1964.

- 1 2 "Our Musical Score: Columbia Records 1964 LP Chart Performance". Billboard 76 (52): 106–7. 26 December 1964.

- ↑ "Hits of the World: Eire". Billboard 76 (12): 32. 21 March 1964.

- ↑ "Hits of the World: Eire". Billboard 76 (14): 30. 4 April 1964.

- 1 2 Roberts, David (2006). British Hit Singles & Albums (19th ed.). London: Guinness World Records Limited. p. 107. ISBN 1-904994-10-5.

- ↑ Kart, Larry (27 October 1985). "Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem: A Lot of Talent and a Bit o' Blarney". Chicago Tribune: 24.

- ↑ Gordon, Ronni (14 March 1999). "Clancys Headline St. Patrick's Day Party". Sunday Republican (Springfield, MA).

- 1 2 3 Alan Gilsenan (director) (2009). The Yellow Bittern: The Life and Times of Liam Clancy (Documentary/DVD). RTÉ.

- ↑ Clinton, Audrey (15 October 1985). "Makem tours with the Clancy Brothers". Newsday (Long Island, NY). p. 17.

- ↑ McGuinness, Sean (2001). "Tunes 'n' Tales of Ireland – Review". The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ↑ "Tommy Makem (obituary)". Telegraph. 3 August 2007. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ↑ "Liam Clancy dies aged 74". RTÉ News and Current Affairs. 4 December 2009. Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- ↑ "Singer Liam Clancy dies aged 74". The Irish Times. 4 December 2009. Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- ↑ "Top U.S. Artists by Category". Billboard 76 (52): 23–4. 26 December 1964.

- ↑ Bob Dylan, Playboy interview, 1978.

- ↑ Hitchner, Earle, "Trad Beat: Honoring Paddy Clancy," Irish Echo, 1999.

- ↑ Cohen, Ronald D. (2002). Rainbow Quest: The Folk Music Revival and American Society, 1940–1970. University of Massachusetts Press. p. 189. ISBN 1558493484.

- ↑ Rainbow Quest, p. 145, 160.

- ↑ Sounes, Howard, Down the Highway: The Life of Bob Dylan, Grove Press, 2002.

- ↑ Dylan, Bob; Bono, "The Bono Vox Interview," Hot Press, 8 July 1984.

- ↑ Sounes, Down the Highway: The Life of Bob Dylan, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Woodsongs Archive Scroll down to show 262, both audio and video available

- ↑ "What's Real in 'Inside Llewyn Davis': The Clancy Brothers," Rolling Stone, 2014.

- ↑ Haglund, David, “The People Who Inspired Inside Llewyn Davis,” Slate, 2 December 2013.

- ↑ Hornaday, Ann, "'Inside Llewyn Davis' review: A poignant evocation of the 1960s New York folk scene," Washington Post

- ↑ Amazon: Ain't it Grand Boys: A Collection of Unissued Gems (1995)

External links

- Annual Clancy Brothers Festival

- The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem – Biography and Discographies at the Balladeers

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|