Paul Butterfield

| Paul Butterfield | |

|---|---|

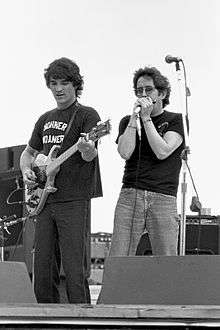

Butterfield performing at the Woodstock Reunion 1979. | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Paul Vaughn Butterfield[1] |

| Born |

December 17, 1942[1] Chicago, Illinois[1] |

| Died |

May 4, 1987 (aged 44)[2] North Hollywood, California[2] |

| Genres | Blues rock, Chicago blues, blue-eyed soul |

| Occupation(s) | Musician |

| Instruments | Harmonica, vocals, guitar, keyboards, flute |

| Years active | 1963–1987 |

| Labels | Elektra, Bearsville |

| Associated acts | The Paul Butterfield Blues Band, Paul Butterfield's Better Days |

| Notable instruments | |

| Hohner Marine Band harmonica | |

Paul Vaughn Butterfield (December 17, 1942 – May 4, 1987) was an American blues singer and harmonica player. After early training as a classical flutist, Butterfield developed an interest in blues harmonica. He explored the blues scene in his native Chicago, where he was able to meet Muddy Waters and other blues greats who provided encouragement and a chance to join in the jam sessions. Soon, Butterfield began performing with fellow blues enthusiasts Nick Gravenites and Elvin Bishop.

In 1963, he formed the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, who recorded several successful albums and were a popular fixture on the late-1960s concert and festival circuit, with performances at the Fillmores, Monterey Pop Festival, and Woodstock. They became known for combining electric Chicago blues with a rock urgency as well as their pioneering jazz fusion performances and recordings. After the breakup of the group in 1971, Butterfield continued to tour and record in a variety of settings, including with Paul Butterfield's Better Days, his mentor Muddy Waters, and members of the roots-rock group The Band.

While still recording and performing, Butterfield died in 1987 at age 44 of a heroin overdose. Music critics have acknowledged his development of an original approach that places him among the best-known blues harp players. In 2006, he was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inducted the Paul Butterfield Blues Band in 2015. Both panels noted his harmonica skills as well as his contributions to bringing blues-style music to a younger and broader audience.

Career

Butterfield was born in Chicago and raised in the city's Hyde Park neighborhood. The son of a lawyer and a painter, he attended the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools, a private school associated with the University of Chicago. Exposed to music at an early age, he studied classical flute with Walfrid Kujala of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.[3] Butterfield was also athletic and was offered a track scholarship to Brown University.[3] However, a knee injury and a growing interest in blues music sent him in a different direction. He developed a love for blues harmonica and a friendship with guitarist and singer-songwriter Nick Gravenites, who shared an interest in authentic blues music.[4] By the late 1950s, they started visiting some of Chicago's blues clubs and met musicians such as Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, Little Walter, and Otis Rush, who encouraged them and occasionally let them sit in on jam sessions. The pair were soon performing as "Nick and Paul" in college-area coffee houses.[5]

In the early 1960s, Butterfield attended the University of Chicago, where he met aspiring blues guitarist Elvin Bishop.[6][7] Both began devoting more time to music than studies and soon became full-time musicians.[5] Eventually, Butterfield, who sang and played harmonica, and Bishop, accompanying him on guitar, were offered a regular gig at Big John's, an important folk club in the Old Town district on Chicago's north side.[8] With this prospect, they were able to entice bassist Jerome Arnold and drummer Sam Lay (both from Howlin' Wolf's touring band) into forming a group in 1963. Their engagement at the club was highly successful and brought the group to the attention of record producer Paul A. Rothchild.[9]

Butterfield Blues Band with Bloomfield

During their engagement at Big John's, Butterfield met and occasionally sat in with guitarist Mike Bloomfield, who was also playing at the club.[6] By chance, producer Rothchild witnessed one of their performances and was impressed by the obvious chemistry between the two. He convinced Butterfield to bring Bloomfield into the band, and they were signed to Elektra Records.[9] Their first attempt to record an album in December 1964 did not meet Rothchild's expectations, although an early version of "Born in Chicago", written by Nick Gravenites, was included on the 1965 Elektra sampler Folksong '65 and created interest in the band (additional early recordings were later released on the 1966 Elektra compilation, What's Shakin' and The Original Lost Elektra Sessions in 1995). In order to better capture their sound, Rothchild convinced Elektra president Jac Holzman to record a live album.[10] In the spring of 1965, the Butterfield Blues Band was recorded at New York's Cafe Au Go Go. These recordings also failed to satisfy Rothchild, but the group's appearances at the club brought them to the attention of the East Coast music community.[6] Rothchild was able to get Holzman to agree to a third attempt at recording an album.[lower-alpha 1]

During the recording sessions, Paul Rothchild had assumed the role of group manager and used his folk contacts to secure the band more and more engagements outside of Chicago.[12] At the last minute, Butterfield and band were booked to perform at the Newport Folk Festival in July 1965.[6] They were scheduled as the opening act the first night when the gates opened and again the next afternoon in an urban blues workshop at the festival.[12] Despite limited exposure during their first night and a dismissive introduction the following day by folklorist/blues researcher Alan Lomax,[13][lower-alpha 2] the band was able to attract an unusually large audience for a workshop performance. Maria Muldaur, with her husband Geoff, who later toured and recorded with Butterfield, recalled the group's performance as stunning – it was the first time that many of the mostly folk-music fans had experienced a high-powered electric blues combo.[12] Among those who took notice was festival regular Bob Dylan, who invited the band to back him for his first live electric performance. With little rehearsal, Dylan performed a short, four-song set the next day with Bloomfield, Arnold, and Lay (along with Al Kooper and Barry Goldberg).[13][14] It was not received well by some of the folk music establishment and generated a lot of controversy;[3] however, it was a watershed event and brought the band to the attention of a much larger audience.[12]

After adding keyboardist Mark Naftalin, the band's debut album was finally successfully recorded in mid-1965. Simply titled The Paul Butterfield Blues Band, it was released later in 1965. The opening song, a newer recording of the previously released "Born in Chicago", is an upbeat blues rocker and set the tone for the album, which included a mix of blues standards, such as "Shake Your Moneymaker", "Blues with a Feeling", and "Look Over Yonders Wall" and band compositions. The album, described as a "hard-driving blues album that, in a word, rocked",[8] reached number 123 in the Billboard 200 album chart in 1966,[15] although its influence was felt beyond its sales figures.[9]

When Sam Lay became ill, jazz drummer Billy Davenport was invited to replace him.[9] In July 1966, the sextet recorded their second album East-West, which was released a month later. The album consists of more varied material, with the band's interpretations of blues (Robert Johnson's "Walkin' Blues"), rock (Michael Nesmith's "Mary, Mary"), R&B (Allen Toussaint's "Get Out of My Life, Woman"), and jazz selections (Nat Adderley's "Work Song"). East-West reached number 65 in the album chart.[15]

The thirteen-minute instrumental title track "East-West" incorporates Indian raga influences and features some of the earliest jazz-fusion/blues rock excursions, with extended solos by Butterfield and guitarists Mike Bloomfield and Elvin Bishop.[7] It has been identified as "the first of its kind and marks the root from which the acid rock tradition emerged".[16] Live versions of the song could last nearly an hour and performances at the San Francisco Fillmore Auditorium "were a huge influence on the city's jam bands".[17] Bishop recalled, "Quicksilver, Big Brother, and the Dead – those guys were just chopping chords. They had been folk musicians and weren't particularly proficient playing electric guitar – [Bloomfield] could play all these scales and arpeggios and fast time-signatures ... He just destroyed them".[17] Several live versions of "East-West" from this period were later released on East-West Live in 1996.

While in England in November 1966, Paul Butterfield recorded several songs with John Mayall & the Bluesbreakers, who had recently finished their A Hard Road album.[18] Both Butterfield and Mayall contribute vocals, with Butterfield's Chicago-style blues harp being featured. Four songs were released in the UK on a 45 rpm EP in January 1967, titled John Mayall's Bluesbreakers with Paul Butterfield.[lower-alpha 3]

Later Butterfield Blues Band

In spite of their success, the Butterfield Blues Band lineup soon changed; Arnold and Davenport left the band, and Bloomfield went on to form his own group, Electric Flag.[9] With Bishop and Naftalin remaining on guitar and keyboards, they added bassist Bugsy Maugh, drummer Phillip Wilson, and saxophonists David Sanborn and Gene Dinwiddie. Together, they recorded the band's third album, The Resurrection of Pigboy Crabshaw, in 1967. The album cut back on the extended instrumental jams and went in a more rhythm and blues-influenced horn-driven direction with songs such as Charles Brown's "Driftin' Blues" (retitled "Driftin' and Driftin'"), Otis Rush's "Double Trouble", and Junior Parker's "Driving Wheel".[19] The Resurrection of Pigboy Crabshaw was Butterfield's highest charting album, reaching number 52 on the album chart.[15] On June 17, 1967, most of this lineup performed at the seminal Monterey Pop Festival.[lower-alpha 4][20]

Their next album in 1968, In My Own Dream, saw the band continuing to move away from their hard Chicago-blues roots towards a more soul-influenced horn-based sound. With Butterfield only singing three songs, the album featured more band contributions[21] and reached number 79 in the Billboard album chart.[15] By the end of 1968, both Bishop and Naftalin had left the band.[9] In April 1969, Butterfield took part in a concert at Chicago's Auditorium Theater and a subsequent recording session organized by record producer Norman Dayron, featuring Muddy Waters and backed by Otis Spann, Mike Bloomfield, Sam Lay, Donald "Duck" Dunn, and Buddy Miles. Such Muddy Waters' warhorses as "Forty Days and Forty Nights", "I'm Ready", "Baby, Please Don't Go", and "Got My Mojo Working" were recorded and later released on his Fathers and Sons album. Muddy Waters commented "We did a lot of the things over we did with Little Walter and Jimmy Rogers and Elgin [Evans] on drums [Waters' original band] ... It's about as close as I've been [to that feel] since I first recorded it".[22] To one reviewer, these recordings represent Paul Butterfield's best performances.[23]

Butterfield was invited to perform at the Woodstock Festival on August 18, 1969. He and his band performed seven songs, and although their performance did not appear in the resulting Woodstock film, one song, "Love March", was included on the Woodstock: Music from the Original Soundtrack and More album released in 1970. In 2009, Butterfield was included in the expanded 40th Anniversary Edition Woodstock video and an additional two songs appeared on the Woodstock: 40 Years On: Back to Yasgur's Farm box-set album. With only Butterfield remaining from the original lineup, 1969's Keep On Moving album was produced by veteran R&B producer/songwriter Jerry Ragovoy, reportedly brought in by Elektra to turn out a "breakout commercial hit".[3] The album was not embraced by critics or long-time fans;[24] however, it reached number 102 in the Billboard album chart.[15]

A live double album by the Butterfield Blues Band, simply titled Live, was recorded March 21–22, 1970 at the The Troubadour in West Hollywood, California. By this time, the band included a four-piece horn section in what has been described as a "big-band Chicago blues with a jazz base"; Live provides perhaps the best showcase for this unique "blues-jazz-rock-R&B hybrid sound ".[25] After the release of another soul-influenced album, Sometimes I Just Feel Like Smilin' in 1971, the Paul Butterfield Blues Band disbanded.[9] In 1972, a retrospective or their career, Golden Butter: The Best of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band was released by Elektra.

Better Days and solo

After his Blues Band's breakup and no longer with Elektra, Butterfield retreated to the community of Woodstock, New York where he eventually formed his next band.[12] Named "Paul Butterfield's Better Days", the new group included drummer Chris Parker, guitarist Amos Garrett, singer Geoff Muldaur, pianist Ronnie Barron and bassist Billy Rich. In 1972–1973, the group released the self-titled Paul Butterfield's Better Days and It All Comes Back on Albert Grossman's Bearsville Records. The albums reflected the influence of the participants and explored more roots- and folk-based styles.[26] Although without an easily defined commercial style, both reached the album chart.[15] Paul Butterfield's Better Days, however, did not last to record a third studio album, although their Live at Winterland Ballroom, recorded in 1973, was released in 1999.[27]

After the breakup of Better Days, Butterfield pursued a solo career and appeared as a sideman in several different musical settings.[8] In 1975, he again joined Muddy Waters to record Waters' last album for Chess Records, The Muddy Waters Woodstock Album.[28] The album was recorded at Levon Helm's Woodstock studio with Garth Hudson and members of Muddy Waters' touring band. In 1976, Butterfield performed at The Band's final concert, The Last Waltz. Together with the Band, he performed the song "Mystery Train" and backed Muddy Waters on "Mannish Boy".[29] Butterfield kept up his association with former members of the Band, touring and recording with Levon Helm and the RCO All Stars in 1977.[7] In 1979, Butterfield toured with Rick Danko and in 1984 a live performance with Danko and Richard Manuel was recorded and released as Live at the Lonestar in 2011.[30]

As a solo act with backing musicians, Butterfield continued to tour and recorded the misguided and overproduced Put It in Your Ear in 1976 and North South in 1981, with strings, synthesizers, and pale funk arrangements.[3] In 1986, Butterfield released his final studio album, The Legendary Paul Butterfield Rides Again, which again was a poor attempt at a comeback with an updated rock sound. On April 15, 1987, he participated in B.B. King & Friends, a concert that included Eric Clapton, Etta James, Albert King, Stevie Ray Vaughan, and others.[31]

Legacy

Aside from "rank[ing] among the most influential harp players in the Blues",[32] Paul Butterfield has also been seen as pointing blues-based music in new, innovative directions.[33] AllMusic critic Steve Huey commented

It's impossible to overestimate the importance of the doors Butterfield opened: before he came to prominence, white American musicians treated the blues with cautious respect, afraid of coming off as inauthentic. Not only did Butterfield clear the way for white musicians to build upon blues tradition (instead of merely replicating it), but his storming sound was a major catalyst in bringing electric Chicago blues to white audiences who'd previously considered acoustic Delta blues the only really genuine article.[3]

In 2006, Paul Butterfield was inducted into the Blues Foundation Blues Hall of Fame, which noted that "the albums released by the Butterfield Blues Band brought Chicago Blues to a generation of Rock fans during the 1960s and paved the way for late 1960s electric groups like Cream".[32] The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inducted the Paul Butterfield Blues Band in 2015.[34] In the induction biography, they commented "the Butterfield Band converted the country-blues purists and turned on the Fillmore generation to the pleasures of Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, Little Walter, Willie Dixon and Elmore James".[14]

Harmonica style

As with many Chicago blues-harp players, Paul Butterfield approached the instrument like a horn, preferring single notes to chords, and used it for soloing.[8] His style has been described as "always intense, understated, concise, and serious"[33] and he is "known for purity and intensity of his tone, his sustained breath control, and his unique ability to bend notes to his will".[35] Although his choice of notes has been compared to Big Walter Horton's, he was never seen as an imitator of any particular harp player.[6][8][lower-alpha 5] Rather, he developed "a style original and powerful enough to place him in the pantheon of true blues greats".[3]

Butterfield played Hohner harmonicas, and later endorsed them, and preferred the diatonic ten-hole Marine Band model.[36] Although not published until 1997, Butterfield authored a harmonica instruction book, Paul Butterfield Teaches Blues Harmonica Master Class[37] a few years before his death. In it, he explains various techniques, demonstrated on an accompanying CD.[35] Butterfield played mainly in the cross harp or second position, although he occasionally used a chromatic harmonica.[8] Reportedly left-handed, he held the harmonica opposite to a right-handed player, i.e., in his right hand upside-down (with the low notes to the right), using his left hand for muting effects.[lower-alpha 6]

Also similar to other electric Chicago-blues harp players, Butterfield frequently used amplification to achieve his sound.[8] Producer Rothchild noted that Butterfield favored an Altec harp microphone run through an early model Fender tweed amplifier.[38] Beginning with The Resurrection of Pigboy Crabshaw album, he began using an acoustic-harmonica style, following his shift to a more R&B-based approach.[6]

Personal life

By all accounts, Paul Butterfield was absorbed in his music. According to his brother Peter

He listened to records and went places, but he also spent an awful lot of time, by himself, playing [harmonica]. He'd play outdoors. There's a place called The Point in Hyde Park [Chicago], a promontory of land that sticks out into Lake Michigan, and I can remember him out there for hours playing. He was just playing all the time ... It was a very solitary effort. It was all internal, like he had a particular sound he wanted to get and he just worked to get it.[8]

Producer Norman Dayron recalled the young Butterfield as "very quiet and defensive and hard-edged. He was this tough Irish Catholic, kind of a hard guy. He would walk around in black shirts and sunglasses, dark shades and dark jackets ... Paul was hard to be friends with."[4] Although they later became close, Michael Bloomfield commented on his first impressions of Butterfield: "He was a bad guy. He carried pistols. He was down there on the South Side, holding his own. I was scared to death of that cat".[39] Writer and AllMusic founder Michael Erlewine, who knew Butterfield during his early recording career, described him as "always intense, somewhat remote, and even, on occasion, downright unfriendly".[8] He remembered Butterfield as "not much interested in other people".[8]

By 1971, Butterfield had purchased his first house in rural Woodstock, New York and began enjoying family life with his second wife Kathy and their new infant son, Lee. According to Maria Muldaur, she and her husband were frequent dinner guests, which usually also involved sitting around a piano and singing songs.[12] Although she doubted her abilities, "it was Butter that first encouraged me to let loose and just sing the blues [and] not to worry about singing pretty or hitting all the right notes ... He loosened all the levels of self-consciousness and doubt out of me ... And he'll forever live in my heart for that and for respecting me as a fellow musician.[12]

Death

Beginning in 1980, Paul Butterfield underwent several surgical procedures to relieve his peritonitis, a serious and painful inflammation of the intestines.[7] Although he had been opposed to hard drugs as a bandleader, he began using painkillers, including heroin, which led to an addiction. These problems and the drug-related death of his friend and one-time musical partner Mike Bloomfield weighed heavily on him.[3] On May 4, 1987 at age 44, Paul Butterfield died at his apartment in the North Hollywood district of Los Angeles. An autopsy by the county coroner concluded that he was the victim of an accidental drug overdose, with "significant levels of morphine (heroin)".[2]

By the time of his death, Paul Butterfield was out of the commercial mainstream. Although for some, he was very much the bluesman, Maria Muldaur commented "he had the whole sensibility and musicality and approach down pat ... He just went for it and took it all in, and he embodied the essence of what the blues was all about. Unfortunately, he lived that way a little too much".[12]

Discography

In 1964, Butterfield began his association with Elektra Records and eventually recorded seven albums for the label.[40] After the breakup of the Butterfield Blues Band in 1971, he recorded four albums for manager Albert Grossman's Bearsville Records – two with Paul Butterfield's Better Days and two solo.[40] His last solo album was released by Amherst Records.[40]

After his death in 1987, his former record companies released a number of live albums and compilations. Except where noted, the following albums are listed as "The Paul Butterfield Blues Band".

Studio albums

The Butterfield Blues Band

- The Paul Butterfield Blues Band (1965)

- East-West (1966)

- The Resurrection of Pigboy Crabshaw (1967)

- In My Own Dream (1968)

- Keep On Moving (1969)

- Sometimes I Just Feel Like Smilin' (1971)

Paul Butterfield's Better days

- Better Days (1973)

- It All Comes Back (1973)

Paul Butterfield

- Put It in Your Ear (1976)

- North-South (1981)

- The Legendary Paul Butterfield Rides Again (1986)

Live albums

- Live (1970, reissued 2005 with bonus tracks)

- Strawberry Jam (1996, recorded 1966–1968)

- East-West Live (1996, recorded 1966–1967)

- Live at Unicorn Coffee House (various names and dates, bootleg recording 1966)

- Live at Winterland Ballroom – Paul Butterfield's Better Days (1999, recorded 1973)

- Rockpalast: Blues Rock Legends, Vol. 2 – Paul Butterfield Band (2008, recorded 1978)

- Live at the Lone Star – Rick Danko, Richard Manuel & Paul Butterfield (2011, recorded 1984)

Butterfield compilation albums

- Golden Butter: The Best of the Butterfield Blues Band (1972)

- The Original Lost Elektra Sessions (1995, recorded 1964)

- An Anthology: The Elektra Years (2 CDs, 1997)

- Paul Butterfield's Better Days: Bearsville Anthology – Paul Butterfield's Better Days (2000)

- Hi-Five: The Paul Butterfield Blues Band (2006 EP)

Compilation albums/videos with various artists

- Folksongs '65 (1965)

- What's Shakin' (1966)

- Festival (1967 film, including 1965 appearance with Dylan)

- You Are What You Eat (1968 film soundtrack)

- Woodstock: Music from the Original Soundtrack and More (1970, recorded 1969)

- Woodstock 2 (1971, recorded 1969)

- An Offer You Can't Refuse (1972, recorded 1963)

- Woodstock '79 (1991 video, filmed 1979)

- Woodstock: Three Days of Peace and Music (1994, recorded 1969)

- The Monterey International Pop Festival June 16–17–18 30th Anniversary Box Set (1997, recorded 1967)

- The Complete Monterey Pop Festival (2002 video, filmed 1967)

- Woodstock: 40 Years On: Back to Yasgur's Farm (2009, recorded 1969)

- Woodstock: 40th Anniversary Ultimate Collector's Edition (2009 video, filmed 1969)

As an accompanist

- John Mayall's Bluesbreakers with Paul Butterfield – John Mayall & the Bluesbreakers (1967 EP)

- Blues at Midnight (various names and dates) – Jimi Hendrix, B.B. King, et al. (bootleg of jam recorded 1968)

- Fathers and Sons – Muddy Waters (1969, reissued 2001 with bonus tracks)

- Give It Up – Bonnie Raitt (1972)

- Steelyard Blues – Mike Bloomfield, Nick Gravenites, Maria Muldaur, et al. (1973 film soundtrack)

- That's Enough for Me – Peter Yarrow (1973)

- Woodstock Album – Muddy Waters (1975)

- Levon Helm & The RCO All-Stars (1977)

- The Last Waltz – The Band (1978)

- Elizabeth Barraclough – Elizabeth Barraclough (1978)

- Hi! – Elizabeth Barraclough (1979)

- B.B. King & Friends (various names and dates) – B.B King, Eric Clapton, Stevie Ray Vaughan, et al. (bootleg video of television special filmed 1987)

- Heart Attack – Little Mike & the Tornados (1990, recorded 1986)[lower-alpha 7]

Tribute albums

- A Tribute to Paul Butterfield – Robben Ford and the Ford Blues Band (2001)

- The Butterfield/Bloomfield Concert – The Ford Blues Band with Robben Ford and Chris Cain (2006)

Notes

- Footnotes

- ↑ Rothchild also recalled Holzman's approval came with the warning, "Rothchild, do not fuck this up!" [11]

- ↑ Albert Grossman, who had agreed to take over management of the band the night before, was incensed at Lomax's perceived insults and an argument backstage led to an altercation between the two.

- ↑ Presumably because of licensing restrictions, the EP was marked "For sale in the U.K. only", although it soon found its way to some specialty record retailers in the U.S. The songs were later included as bonus tracks on the 2003 expanded 2-CD reissue of A Hard Road with most of Peter Green's recordings with Mayall.

- ↑ Billy Davenport played the drums and Keith Johnson contributed trumpet in place of David Sanborn on saxophone. Former bandmate Mike Bloomfield also performed the same day at Monterey with his new group Electric Flag.

- ↑ Compare Butterfield's reading of "Off the Wall" from What's Shakin' or "Everything Going to Be Alright" from Live to Little Walter's originals.

- ↑ Erlewine wrote that he held the harmonica in his left hand with the low notes to the left, but this is contradicted by a photo on the front cover of Butterfield's instructional book and his filmed performance at Monterey Pop, both clearly showing him holding it in his right and using his left for muting.

- ↑ A review of Heart Attack states "four cuts feature Paul Butterfield on harp (believed to be his last recordings)." Frantz, Niles J. "Heart Attack – Album Review". AllMusic. Rovi Corp. Retrieved August 4, 2013.

- Citations

- 1 2 3 "Paul Butterfield". Sweet Home Cook County. Cook County Clerk's Office. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Musician's Death Laid to Overdose". Los Angeles Times. June 13, 1987. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Huey, Steve. "Paul Butterfield – Biography". AllMusic. Rovi Corp. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- 1 2 Wolkin, Keenom 2000, p. 40.

- 1 2 Milward 2013, p. 66.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Field 2000, pp. 212–214.

- 1 2 3 4 "Paul Butterfield – Biography". Rolling Stone. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Erlewine 1996, p. 41.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Leggett, Steve. "The Paul Butterfield Blues Band – Biography". AllMusic. Rovi Corp. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ↑ Rothchild 1995, pp. 1–4.

- ↑ Rothchild 1995, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Ellis 1997

- 1 2 Marcus 2006, pp. 154–155.

- 1 2 "The Paul Butterfield Blues Band Biography". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Paul Butterfield – Awards". AllMusic. Rovi Corp. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- ↑ Tamarkin, Jeff (1996). "East-West". All Music Guide to the Blues. Miller Freeman Books. p. 42. ISBN 0-87930-424-3.

- 1 2 Houghton 2010, p. 195.

- ↑ Schinder, Scott (2003). A Hard Road – Expanded Edition (CD booklet). John Mayall & the Bluesbreakers. Deram Records. pp. 10, 14. B0001083-02.

- ↑ Erlewine, Michael (1996). "The Resurrection of Pigboy Crabshaw". All Music Guide to the Blues. Miller Freeman Books. p. 42. ISBN 0-87930-424-3.

- ↑ Perone, James (2005). Woodstock: An Encyclopedia of the Music and Art Fair. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-313-33057-5.

- ↑ Eder, Bruce. "In My Own Dream – Album Review". AllMusic. Rovi Corp. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ↑ Gordon 2002, p. 207.

- ↑ Herzhaft 1992, p. 371.

- ↑ Campbell, Al. "Keep on Moving – Album review". AllMusic. Rovi Corp. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- ↑ Eder, Bruce. "Live – Album Review". AllMusic. Rovi Corp. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- ↑ "Paul Butterfield's Better Days – Album Review". AllMusic. Rovi Corp. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ↑ "Live at Winterland Ballroom". AllMusic. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ↑ Gordon 2002, p. 247.

- ↑ Gordon 2002, p. 253.

- ↑ "Rick Danko, Richard Manuel & Paul Butterfield Live at the Lone Star 1984 – Overview". AllMusic. Rovi Corp. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ↑ "B.B. King & Friends: A Night of Blistering Blues – Overview". AllMusic. Rovi Corp. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- 1 2 "Paul Butterfield". Blues Hall of Fame – 2006 Inductees. The Blues Foundation. 2006. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- 1 2 Dicaire 2001, p. 59–60

- ↑ "The 2015 Inductees". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- 1 2 "Paul Butterfield Teaches Blues Harmonica Master Class". Homespun Music Instruction. Homespun Tapes. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- ↑ Welding, Pete (1965). The Paul Butterfield Blues Band (Album notes). Paul Butterfield Blues Band. Elektra Records. EKL-294/EKS-7294.

- ↑ Butterfield, Paul (1997). Paul Butterfield Teaches Blues Harmonica Master Class. Homespun Listen and Learn Series. ISBN 978-0-7935-8130-6.

- ↑ Rothchild 1995, p. 3.

- ↑ Wolkin, Keenom 2000, p. 93.

- 1 2 3 "Paul Butterfield – Discography". AllMusic. Rovi Corp. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- References

- Dicaire, David (2001). More Blues Singers: Biographies of 50 Artists from the Later 20th Century. Mcfarland & Co Inc. ISBN 978-0-7864-1035-4.

- Ellis III, Tom (Spring 1997). "Paul Butterfield: From Newport to Woodstock". Blues Access (Blues Access) (29).

- Erlewine, Michael (1996). "Paul Butterfield Blues Band". All Music Guide to the Blues. Miller Freeman Books. ISBN 0-87930-424-3.

- Field, Kim (2000). Harmonicas, Harps, and Heavy Breathers: The Evolution of the People's Instrument. Cooper Square Press. ISBN 978-0-8154-1020-1.

- Gioia, Ted (2008). Delta Blues. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-33750-1.

- Gordon, Robert (2002). Can't Be Satisfied: The Life and Times of Muddy Waters. Little, Brown. ISBN 0-316-32849-9.

- Herzhaft, Gerard (1992). "Paul Butterfield". Encyclopedia of the Blues. University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 1-55728-252-8.

- Houghton, Mick (2010). Becoming Elektra: True Story Of Jac Holzman's Visionary Record Label. Jawbone Press. ISBN 978-1-906002-29-9.

- Marcus, Greil (2006). Like a Rolling Stone: Bob Dylan at the Crossroads. Public Affairs. ISBN 978-1-58648-382-1.

- Milward, John (2013). Crossroads: How the Blues Shaped Rock 'n' Roll (and Rock Saved the Blues). Northeastern. ISBN 978-1-55553-744-9.

- Rothchild, Paul (1995). The Original Lost Elektra Sessions (Media notes). Paul Butterfield Blues Band. Elekrtra Traditions/Rhino Records. R2 73305.

- Shadwick, Keith (2001). "Paul Butterfield". The Encyclopedia of Jazz & Blues. Oceana. ISBN 978-0-681-08644-9.

- Wolkin, Jan Mark; Keenom, Bill (2000). Michael Bloomfield – If You Love These Blues: An Oral History. Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-617-5.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paul Butterfield. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|