Garter snake

| Garter snake | |

|---|---|

| |

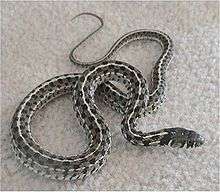

| Coast garter snake Thamnophis elegans terrestris | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Colubridae |

| Subfamily: | Natricinae |

| Genus: | Thamnophis Fitzinger, 1843 |

| Species | |

|

See Taxonomy section. | |

| |

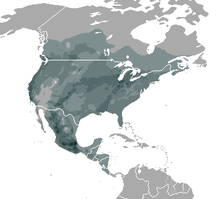

| Thamnophis distribution | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Atomarchus, Chilopoma, Coluber, Eutaenia, Eutainia, Leptophis, Natrix, Nerodia, Phamnovis, Prymnomiodon, Stypocemus, Tropidonote, Tropidonotus, Vipera[1] | |

Garter snake ‒ also called garden snake or gardener snake ‒ is the common name given to harmless, small to medium-sized snakes belonging to the genus Thamnophis. Endemic to North America, they can be found from the Subarctic plains of Canada to Central America. The garter snake is the state reptile of Massachusetts.[2]

With no real consensus on the classification of species of Thamnophis, disagreement between taxonomists and sources, such as field guides, over whether two types of snakes are separate species or subspecies of the same species is common. Garter snakes are closely related to the genus Nerodia (water snakes), with some species having been moved back and forth between genera.

Habitat

Garter snakes are present throughout most of North America. They have a wide distribution due to their varied diets and adaptability to different habitats, with varying proximity to water; however, in the western part of North America, these snakes are more aquatic than in the eastern portion. Garter snakes populate a variety of habitats, including forests, woodlands, fields, grasslands, and lawns. They almost exclusively inhabit areas with some form of water, often an adjacent wetland, stream, or pond. This reflects the fact that amphibians are a large part of their diet.

Conservation status

Despite the decline in their population from collection as pets (especially in the more northerly regions in which large groups are collected at hibernation), pollution of aquatic areas, and the introduction of bullfrogs as potential predators, garter snakes are still some of the most commonly found reptiles in much of their ranges. The San Francisco garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis tetrataenia), however, is an endangered subspecies and has been on the endangered list since 1969. Predation by crawfish has also been responsible for the decline of the narrow-headed garter snake (Thamnophis rufipunctatus).

Diet

Garter snakes, like all snakes, are carnivorous. Their diet consists of almost any creature they are capable of overpowering: slugs, earthworms, leeches, lizards, amphibians (including frog eggs), ants, crickets, minnows, and rodents. When living near water, they will eat other aquatic animals. The ribbon snake (Thamnophis sauritus) in particular favors frogs (including tadpoles), readily eating them despite their strong chemical defenses. Food is swallowed whole. Garter snakes often adapt to eating whatever they can find, and whenever, because food can be scarce or abundant. Although they feed mostly on live animals, they will sometimes eat eggs.

Coevolution of garter snakes and toxic newts

Evidence suggests that garter snake and newt populations share an evolutionary link in their levels of tetrodotoxin (TTX) resistance, implying coevolution between predator and prey.[3]

Behavior

Garter snakes have complex systems of pheromonal communication. They can find other snakes by following their pheromone-scented trails. Male and female skin pheromones are so different as to be immediately distinguishable. However, male garter snakes sometimes produce both male and female pheromones. During the mating season, this ability fools other males into attempting to mate with them. This causes the transfer of heat to them in kleptothermy, which is an advantage immediately after hibernation, allowing them to become more active.[4] Male snakes giving off both male and female pheromones have been shown to garner more copulations than normal males in the mating balls that form at the den when females enter the mating melee.

If disturbed, a garter snake may coil and strike, but typically it will hide its head and flail its tail. These snakes will also discharge a malodorous, musky-scented secretion from a gland near the cloaca. They often use these techniques to escape when ensnared by a predator. They will also slither into the water to escape a predator on land. Hawks, crows, raccoons, crayfish, and other snake species (such as the coral snake and king snake) will eat garter snakes, with even shrews and frogs eating the juveniles.

Being heterothermic, like all reptiles, garter snakes bask in the sun to regulate their body temperature. During hibernation, garter snakes typically occupy large, communal sites called hibernacula. These snakes will migrate large distances to brumate.

Reproduction

Garter snakes go into brumation before they mate. They stop eating for about two weeks beforehand to clear their stomachs of any food that would rot there otherwise. Garter snakes begin mating as soon as they emerge from brumation. During the mating season, the males mate with several females. In chillier parts of their range, male common garter snakes awaken from brumation first, giving themselves enough time to prepare to mate with females when they finally appear. Males come out of their dens and, as soon as the females begin coming out, surround them. Female garter snakes produce a sex-specific pheromone that attracts male snakes in droves, sometimes leading to intense male to male competition and the formation of mating balls of up to 25 males per female. After copulation, a female leaves the den/mating area to find food and a place to give birth. Female garter snakes are able to store the male's sperm for years before fertilization. The young are incubated in the lower abdomen, at about the midpoint of the length of the female's body. Garter snakes are ovoviviparous, meaning they give birth to live young. However, this is different from being truly viviparous, which is seen in mammals. Gestation is two to three months in most species. As few as three or as many as 80 snakes are born in a single litter. The young are independent upon birth. On record, the greatest number of garter snakes reported to be born in a single litter is 98.

Garter snakes in captivity

T. sirtalis, T. marcianus and T. sauritus are the most popular species of garter snakes kept in captivity. Baby garter snakes shed their first skin almost immediately, and will begin eating soon after. Garter snakes just require a 10-gallon (38 liter) terrarium. The first shedding is very fine and often disintegrates in minutes under the slithering masses of new snakes. Feeding baby garter snakes can be tricky; earth worms (not compost worms), night crawlers (called dew worms in Canada), silversides (fish), or cut up pieces of pinky mice (thawed fully and waved before the snake on a pair of tongs or hemostats to avoid nipping fingers) will entice appetites.[5] Up to 10 days may pass before a baby garter snake eats; it takes them some time to become accustomed to new settings.

Venom

Garter snakes were long thought to be nonvenomous, but recent discoveries have revealed they do, in fact, produce a mild neurotoxic venom.[6] Garter snakes cannot kill humans with the small amounts of comparatively mild venom they produce, and they also lack an effective means of delivering it. They do have enlarged teeth in the back of their mouths,[7] but their gums are significantly larger.[8][9] The Duvernoy's gland of garters are posterior (to the rear) of the snake's eyes.[10] The mild venom is spread into wounds through a chewing action.

Species and subspecies

- Longnose garter snake, T. angustirostris (Kennicott, 1860)

- Aquatic garter snake, T. atratus

- Santa Cruz garter snake, T. a. atratus (Kennicott, 1860)

- Oregon garter snake, T. a. hydrophilus Fitch, 1936

- Diablo Range garter snake, T. a. zaxanthus Boundy, 1999

- Shorthead garter snake, T. brachystoma (Cope, 1892)

- Butler's garter snake, T. butleri (Cope, 1889)

- Goldenhead garter snake, T. chrysocephalus (Cope, 1885)

- Western aquatic garter snake, T. couchii (Kennicott, 1859)

- Blackneck garter snake, T. cyrtopsis

- Western blackneck garter snake, T. c. cyrtopsis (Kennicott, 1860)

- Eastern garter snake, T. c. ocellatus (Cope, 1880)

- Tropical blackneck garter snake, T. c. collaris (Jan, 1863)

- Tepalcatepec Valley garter snake, T. c. postremus H.M. Smith, 1942

- Yellow-throated garter snake, T. c. pulchrilatus (Cope, 1885)

- Western terrestrial garter snake, T. elegans

- Arizona garter snake, T. e. arizonae V. Tanner & Lowe, 1989

- Mountain garter snake, T. e. elegans (Baird & Girard, 1853)

- Mexican wandering garter snake, T. e. errans H.M. Smith, 1942

- Coast garter snake, T. e. terrestris Fox, 1951

- Wandering garter snake, T. e. vagrans (Baird & Girard, 1853)

- Upper Basin garter snake, T. e. vascotanneri W. Tanner & Lowe, 1989

- Sierra San Pedro Mártir garter snake, T. e. hueyi Van Denburgh & Slevin, 1923

- Thamnophis eques

- Mexican garter snake, T. e. eques (Reuss, 1834)

- Laguna Totolcingo garter snake, T. e. carmenensis Conant, 2003

- T. e. cuitzeoensis Conant, 2003

- T. e. diluvialis Conant, 2003

- T. e. insperatus Conant, 2003

- Northern Mexican garter snake, T. e. megalops (Kennicott, 1860)

- T. e. obscurus Conant, 2003

- T. e. patzcuaroensis Conant, 2003

- T. e. scotti Conant, 2003

- T. e. virgatenuis Conant, 1963

- Montane garter snake, T. exsul Rossman, 1969

- Highland garter snake, T. fulvus (Bocourt, 1893)

- Giant garter snake, T. gigas Fitch, 1940

- Godman's garter snake,[11] T. godmani (Günther, 1894)

- Two-striped garter snake, T. hammondii (Kennicott, 1860)

- Thamnophis lineri Rossman & Burbrink, 2005[12]

- Checkered garter snake, T. marcianus (Baird & Girard, 1853)

- T. m. marcianus (Baird & Girard, 1853)

- T. m. praeocularis (Bocourt, 1892)

- T. m. bovalli (Dunn, 1940)

- Blackbelly garter snake, T. melanogaster

- Tamaulipan montane garter snake, T. mendax Walker, 1955

- Northwestern garter snake, T. ordinoides (Baird & Girard, 1852)

- Western ribbon snake, T. proximus

- Chiapas Highland western ribbon snake, T. p. alpinus Rossman, 1963

- Arid land western ribbon snake, T. p. diabolicus Rossman, 1963

- Gulf Coast western ribbon snake, T. p. orarius Rossman, 1963

- Western ribbon snake, T. p. proximus (Say, 1823)

- Redstripe ribbon snake, T. p. rubrilineatus Rossman, 1963

- Mexican ribbon snake, T. p. rutiloris (Cope, 1885)

- Plains garter snake, T. radix (Baird & Girard, 1853)

- Rossman's garter snake, T. rossmani Conant, 2000

- Narrowhead garter snake, T. rufipunctatus

- T. r. nigronuchalis Thompson, 1957

- T. r. unilabialis W. Tanner, 1985

- T. r. rufipunctatus (Cope, 1875)

- Ribbon snake, T. sauritus

- Bluestripe ribbon snake, T. s. nitae Rossman, 1963

- Peninsula ribbon snake, T. s. sackenii (Kennicott, 1859)

- Eastern ribbon snake, T. s. sauritus (Linnaeus, 1766)

- Northern ribbon snake, T. s. septentrionalis Rossman, 1963

- Longtail Alpine garter snake, T. scalaris (Cope, 1861)

- Short-tail Alpine garter snake, T. scaliger (Jan, 1863)

- Common garter snake, T. sirtalis

- Texas garter snake, T. s. annectens Brown, 1950

- Red-spotted garter snake, T. s. concinnus (Hallowell, 1852)

- New Mexico garter snake, T. s. dorsalis (Baird & Girard, 1853)

- Valley garter snake, T. s. fitchi Fox, 1951

- California red-sided garter snake, T. s. infernalis (Blainville, 1835)

- T. s. lowei W. Tanner, 1988

- Maritime garter snake, T. s. pallidulus Allen, 1899

- Red-sided garter snake, T. s. parietalis (Say, 1823)

- Puget Sound garter snake, T. s. pickeringii (Baird & Girard, 1853)

- Bluestripe garter snake, T. s. similis Rossman, 1965

- Eastern garter snake, T. s. sirtalis (Linnaeus, 1758)

- Chicago garter snake, T. s. semifasciatus (Cope, 1892)

- San Francisco garter snake, T. s. tetrataenia (Cope, 1875)

- Sumichrast's garter snake, T. sumichrasti (Cope, 1866)

- West Coast garter snake, T. valida

- Mexican Pacific Lowlands garter snake, T. v. celaeno (Cope, 1860)

- T. v. isabellae Conant, 1953

- T. v. thamnophisoides Conant, 1961

- T. v. valida (Kennicott, 1860)

See also

- Narcisse Snake Pits

- List of snakes, overview of all snake families and genera

References

- ↑ Wright, A.H. & A.A. Wright. (1957). Handbook of Snakes of the United States and Canada. Comstock. Ithaca and London. p. 755.

- ↑ "Citizen Information Service: State Symbols". Massachusetts State (Secretary of the Commonwealth). Retrieved 2011-01-21.

The Garter Snake became the official reptile of the Commonwealth on January 3, 2007.

- ↑ Williams, Becky L., Edmund D. Brodie, Jr., and Edmund D. Brodie, III (2003). Coevolution of Deadly Toxins and Predator Resistance: Self-Assessment of Resistance by Garter Snakes Leads to Behavioral Rejection of Toxic Newt Prey. Herpetologica 59(2): 155-163.

- ↑ Shine R, Phillips B, Waye H, LeMaster M, Mason RT. (2001). Benefits of female mimicry to snakes. Nature 414:267. doi:10.1038/35104687

- ↑ "Garter Snake Care Sheet". Thamnophis.com.

- ↑ Zimmer, Carl (April 5, 2005). "Open Wide: Decoding the Secrets of Venom". The New York Times.

- ↑ Wright, Debra L.; Kenneth V. Kardong; and David L. Bentley (Sep. 1979). The Functional Anatomy of the Teeth of the Western Terrestrial Garter Snake, Thamnophis elegans. Herpetologica 35(3):223-228. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3891690

- ↑ http://www.anapsid.org/duvernoygland.html

- ↑ http://www.onlinenevada.org/Garter_Snakes

- ↑ http://mastywisdom.blogspot.com/2008/02/pair-of-venom-producing-glands-are.html

- ↑ Beolens B, Watkins M, Grayson M. 2011. The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. (Thamnophis godmani, p. 102).

- ↑ Thamnophis lineri, The Reptile Database.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1906 New International Encyclopedia article Garter-snake. |

- Dutch garter snake site with many pictures

- Anapsid.org: Garter snakes

- Several pictures of a Mexican ribbon snake (Thamnophis proximus rutiloris)

- Plains garter snake - Thamnophis radix species account from the Iowa Reptile and Amphibian Field Guide

- Eastern garter snake - Thamnophis sirtalis Species account from the Iowa Reptile and Amphibian Field Guide.

- Garter snake pictures

- Descriptions and biology of garter snakes

- Genus Thamnophis at The Reptile Database